Egyptian Gods Index

Egyptian Gods Index

Ancient Egyptian Dynasties

Ancient Egyptian Temples

Ancient Egyptian religion was a complex system of polytheistic beliefs and rituals which were an integral part of ancient Egyptian society. It centered on the Egyptians' interaction with a multitude of deities who were believed to be present in, and in control of, the forces and elements of nature. The myths about these gods were meant to explain the origins and behavior of the forces they represented. The practices of Egyptian religion were efforts to provide for the gods and gain their favor.

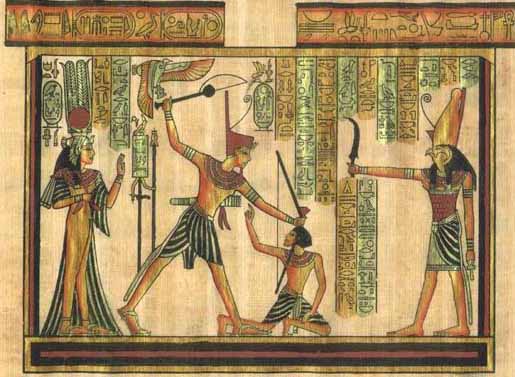

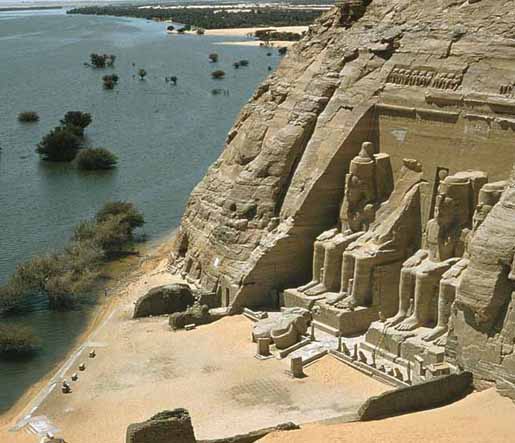

Formal religious practice centered on the pharaoh, the king of Egypt. Although he was a human, the pharaoh was believed to be descended from the gods. He acted as the intermediary between his people and the gods, and was obligated to sustain the gods through rituals and offerings so that they could maintain order in the universe. Therefore, the state dedicated enormous resources to the performance of these rituals and to the construction of the temples where they were carried out. Individuals could also interact with the gods for their own purposes, appealing for their help through prayer or compelling them to act through magic. These popular religious practices were distinct from, but closely linked with, the formal rituals and institutions. The popular religious tradition grew more prominent in the course of Egyptian history as the status of the pharaoh declined. Another important aspect of the religion was the belief in the afterlife and funerary practices. The Egyptians made great efforts to ensure the survival of their souls after death, providing tombs, grave goods, and offerings to preserve the bodies and spirits of the deceased.

The religion had its roots in Egypt's prehistory and lasted for more than 3,000 years. The details of religious belief changed over time as the importance of particular gods rose and declined, and their intricate relationships shifted. At various times certain gods became preeminent over the others, including the sun god Ra, the creator god Amun, and the mother goddess Isis. For a brief period, in the aberrant theology promulgated by the pharaoh Akhenaten, a single god, the Aten, replaced the traditional pantheon. Yet the overall system endured, even through several periods of foreign rule, until the coming of Christianity in the early centuries AD. It left behind numerous religious writings and monument

s, along with significant influences on cultures both ancient and modern.

The beliefs and rituals now referred to as "Ancient Egyptian religion" existed within every aspect of Egyptian culture. Indeed, their language possessed no single term corresponding to the modern European concept of religion. Ancient Egyptian religion was not a monolithic institution, but consisted of a vast and varying set of beliefs and practices, linked by their common focus on the interaction between the world of humans and the world of the divine. The characteristics of the gods who populated the divine realm were inextricably linked to the Egyptians' understanding of the properties of the world in which they lived.

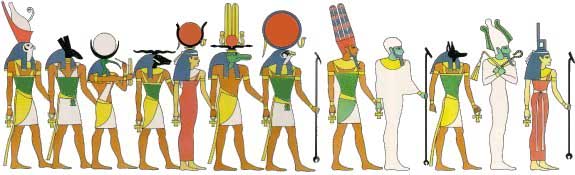

The Egyptians believed that the phenomena of nature were divine forces in and of themselves. These deified forces included the elements, animal characteristics, or abstract forces. The Egyptians believed in a pantheon of gods, which were involved in all aspects of nature and human society. Their religious practices were efforts to sustain and placate these phenomena and turn them to human advantage. This polytheistic system was very complex, as some deities were believed to exist in many different manifestations, and some had multiple mythological roles. Conversely, many natural forces, such as the sun, were associated with multiple deities. The diverse pantheon ranged from gods with vital roles in the universe to minor deities or "demons" with very limited or localized functions. It could include gods adopted from foreign cultures, and sometimes even humans: deceased pharaohs were believed to be divine, and occasionally, distinguished commoners such as Imhotep also became deified.

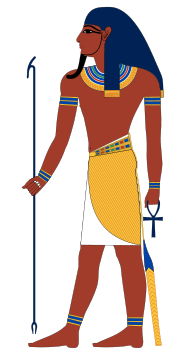

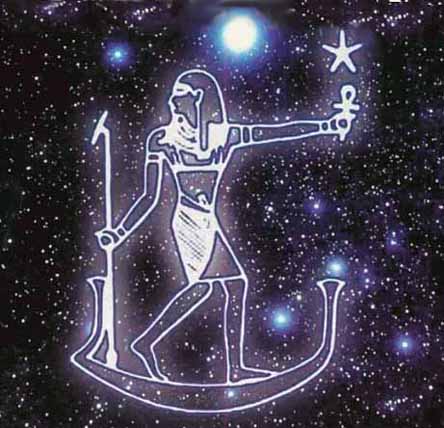

The depictions of the gods in art were not meant as literal representations of how the gods might appear if they were visible, as the gods' true natures were believed to be mysterious. Instead, these depictions gave recognizable forms to the abstract deities by using symbolic imagery to indicate each god's role in nature. Thus, for example, the funerary god Anubis was portrayed as a jackal, a creature whose scavenging habits threatened the preservation of the body, in an effort to counter this threat and employ it for protection. His black skin was symbolic of the color of mummified flesh and the fertile black soil that Egyptians saw as a symbol of resurrection. However, this iconography was not fixed, and many of the gods could be depicted in more than one form.

Many gods were associated with particular regions in Egypt where their cults were most important. However, these associations changed over time, and they did not necessarily mean that the god associated with a place had originated there. For instance, the god Monthu was the original patron of the city of Thebes. Over the course of the Middle Kingdom, however, he was displaced in that role by Amun, who may have arisen elsewhere. The national popularity and importance of individual gods fluctuated in a similar way.

The Egyptian gods had complex interrelationships, which partly reflected the interaction of the forces they represented. The Egyptians often grouped gods together to reflect these relationships. Some groups of deities were of indeterminate size, and were linked by their similar functions. These often consisted of minor deities with little individual identity. Other combinations linked independent deities based on the symbolic meaning of numbers in Egyptian mythology; for instance, pairs of deities usually represent the duality of opposite phenomena. One of the more common combinations was a family triad consisting of a father, mother, and child, who were worshipped together. Some groups had wide-ranging importance. One such group, the Ennead, assembled nine deities into a theological system that was involved in the mythological areas of creation, kingship, and the afterlife. The relationships between deities could also be expressed in the process of syncretism, in which two or more different gods were linked to form a composite deity. This process was a recognition of the presence of one god "in" another when the second god took on a role belonging to the first. These links between deities were fluid, and did not represent the permanent merging of two gods into one; therefore, some gods could develop multiple syncretic connections. Sometimes syncretism combined deities with very similar characteristics. At other times it joined gods with very different natures, as when Amun, the god of hidden power, was linked with Ra, the god of the sun. The resulting god, Amun-Ra, thus united the power that lay behind all things with the greatest and most visible force in nature.

Many deities could be given epithets that seem to indicate that they were greater than any other god, suggesting some kind of unity beyond the multitude of natural forces. In particular, this is true of a few gods who, at various times in history, rose to supreme importance in Egyptian religion. These included the royal patron Horus, the sun god Ra, and the mother goddess Isis. During the New Kingdom (c. 1550-1070 BC), Amun held this position. The theology of the period described in particular detail Amun's presence in and rule over all things, so that he, more than any other deity, embodied the all-encompassing power of the divine.

Because of theological statements like this, many past Egyptologists, such as Siegfried Morenz, believed that beneath the polytheistic traditions of Egyptian religion there was an increasing belief in a unity of the divine, moving toward monotheism. Instances in Egyptian literature where "god" is mentioned without reference to any specific deity would seem to give this view added weight.

However, in 1971 Erik Hornung pointed out that the traits of an apparently supreme being could be attributed to many different gods, even in periods when other gods were preeminent, and further argued that references to an unspecified "god" are meant to refer flexibly to any deity. He therefore argued that, while some individuals may have henotheistically chosen one god to worship, Egyptian religion as a whole had no notion of a divine being beyond the immediate multitude of deities. Yet the debate did not end there; Jan Assmann and James P. Allen have since asserted that the Egyptians did to some degree recognize a single divine force. In Allen's view, the notion of an underlying unity of the divine coexisted inclusively with the polytheistic tradition. It is possible that only the Egyptian theologians fully recognized this underlying unity, but it is also possible that ordinary Egyptians identified the single divine force with a single god in particular situations.

The Egyptians did have an aberrant period of some form of monotheism during the New Kingdom, in which the pharaoh Akhenaten abolished the official worship of other gods in favor of the sun-disk Aten. This is often seen as the first instance of true monotheism in history, although the details of Atenist theology are still unclear. The exclusion of all but one god was a radical departure from Egyptian tradition and some see Akhenaten as a practitioner of monolatry rather than monotheism, as he did not actively deny the existence of other gods; he simply refrained from worshipping any but the Aten. Under Akhenaten's successors Egypt reverted to its traditional religion, and Akhenaten himself came to be reviled as a heretic.

Atenism, or the Amarna heresy, refers to the religious changes associated with the eighteenth dynasty Pharaoh Amenhotep IV, better known under his adopted name, Akhenaten. In the 14th century BC Atenism was Egypt's state religion for around 20 years, before subsequent rulers returned to the traditional gods and the Pharaohs associated with Atenism were erased from Egyptian records.

The Aten - the god of Atenism - first appears in texts dating to the 12th dynasty, in the Story of Sinuhe. Here during the Middle Kingdom, the Aten "as the sun disk was merely one aspect of the sun god Re." The Aten, hence, was a relatively obscure sun god; without the Atenist period, it would barely have figured in Egyptian history. Although there are indications that the Aten was becoming slightly more important in the eighteenth dynasty period - notably Amenhotep III's naming of his royal barge as Spirit of the Aten - it was Amenhotep IV who introduced the Atenist revolution, in a series of steps culminating in the official installment of the Aten as Egypt's sole god.

Although each line of kings prior to the reign of Akhenaten had previously adopted one deity as the royal patron and supreme state god, there had never been an attempt to exclude other deities, and the multitude of gods had been tolerated and worshipped at all times. During the reign of Thutmosis IV it was identified as a distinct solar god, and his son Amenhotep III established and promoted a separate cult for the Aten. There is no evidence however that he (ie. Amenhotep III) neglected the other gods or attempted to promote the Aten as an exclusive deity.

Amenhotep IV initially introduced Atenism in Year 5 of his reign (1348-1346 BC), raising the Aten to the status of supreme god, after initially permitting the continued worship of the traditional gods. To emphasize the change, Aten's name was written in the cartouche form normally reserved for Pharaohs, an innovation of Atenism. This religious reformation appears to coincide with the proclamation of a Sed festival, a sort of royal jubilee intended to reinforce the Pharaoh's divine powers of kingship. Traditionally held in the thirtieth year of the Pharaoh's reign, this possibly was a festival in honor of Amenhotep III, whom some Egyptologists think had a coregency with his son Amenhotep IV of two to twelve years.

Year 5 is believed to mark the beginning of Amenhotep IV's construction of a new capital, Akhetaten (Horizon of the Aten), at the site known today as Amarna. Evidence of this appears on three of the boundary stelae used to mark the boundaries of this new capital. At this time, Amenhotep IV officially changed his name to Akhenaten (Agreeable to Aten) as evidence of his new worship. The date given for the event has been estimated to fall around January 2 of that year. In Year 7 of his reign (1346-1344 BC ) the capital was moved from Thebes to Akhetaten (near modern Amarna), though construction of the city seems to have continued for two more years. In shifting his court from the traditional ceremonial centres Akhenaten was signaling a dramatic transformation in the focus of religious and political power.

The move separated the Pharaoh and his court from the influence of the priesthood and from the traditional centres of worship, but his decree had deeper religious significance too - taken in conjunction with his name change, it is possible that the move to Amarna was also meant as a signal of Akhenaten's symbolic death and rebirth. It may also have coincided with the death of his father and the end of the coregency. In addition to constructing a new capital in honor of Aten, Akhenaten also oversaw the construction of some of the most massive temple complexes in ancient Egypt, including one at Karnak and one at Thebes, close to the old temple of Amun.

In Year 9 (1344-1342 BC), Akhenaten strengthened the Atenist regime, declaring the Aten to be not merely the supreme god, but the only god, a universal deity, and forbidding worship of all others, including the veneration of idols, even privately in people's homes - an arena the Egyptian state had previously not touched in religious terms. Atenism was then based on strict unitarian monotheism, the belief in one single God. Aten was addressed by Akhenaten in prayers, such as the Great Hymn to the Aten: "O Sole God beside whom there is none". The Egyptian people were to worship Akhenaten; only Akhenaten and Nefertiti could worship Aten.

Akhenaten staged the ritual regicide of the old supreme god Amun, and ordered the defacing of Amun's temples throughout Egypt, and of all the old gods. The word for `gods' (plural) was proscribed, and inscriptions have been found in which even the hieroglyph of the word for "mother" has been excised and re-written in alphabetic signs, because it had the same sound in ancient Egyptian as the sound of name of the Theban goddess Mut. Aten's name is also written differently after Year 9, to emphasize the radicalism of the new regime. No longer is the Aten written using the symbol of a rayed solar disc, but instead it is spelled phonetically.

The impact of Akhenaten's religious reform, albeit introduced in steps, is hard to overstate. It is a measure both of Pharaoh's great power, and of the extraordinary circumstances of the time that an equally shocking tone and dramatic transformation was achieved even temporarily, for about twenty years.

The context appears to have been an Egypt hit by catastrophe, seemingly abandoned by the old gods: a series of pandemics is known to have occurred throughout the Near East of this period, and some speculate that it could coincide with the eruption of the volcano of Thera, which would have covered much of Egypt in a layer of destructive ash, killing crops and livestock. Certainly, Amenhotep III's construction of over 700 statues to the god of destruction, Set, suggests Atenism as being more than merely the personal whim of Akhenaten, but at least in part a desperate measure on the part of a Pharaoh responsible for the well-being of his kingdom, above all by ensuring a good relationship with the gods.

In this context, Akhenaten carried out a radical program of religious reform which, for a period of about twenty years, largely supplanted the age-old beliefs and practices of the Egyptian state religion, and deposed its religious hierarchy, headed by the powerful priesthood of Amun at Thebes. For fifteen centuries the Egyptians had worshiped an extended family of gods and goddesses, each of which had its own elaborate system of priests, temples, shrines and rituals. A key feature of these cults was the veneration of images and statues of the gods, which were worshipped in the dark confines of the temples.

The pinnacle of this religious hierarchy was the Pharaoh, who was both king and living god, and the administration of the Egyptian kingdom was thus inextricably bound up with, and largely controlled by, the power and influence of the priests and scribes. Akhenaten's reforms cut away both the philosophical and economic bases of priestly power, abolishing the cults of all other deities, and with them the large and lucrative industry of sacrifices and tributes that the priests controlled.

Initially, Akhenaten presented Aten to the Egyptian people as a variant of the familiar supreme deity Amun-Ra (itself the result of an earlier rise to prominence of the cult of Amun, resulting in Amun becoming merged with the sun god Ra), in an attempt to put his ideas in a familiar religious context. Aten is the name given to the solar disc, whereas the full title of Akhenaten's god was Ra-Horus, who rejoices in the horizon in his name of the light which is in the sun disc. (This is the title of the god as it appears on the numerous stelae which were placed to mark the boundaries of Akhenaten's new capital at Akhetaten.)

However in the ninth year of his reign Akhenaten declared a more radical version of his new religion by declaring Aten not merely the supreme god, but the only god, and that he, Akhenaten, was the only intermediary between the Aten and his people. He even staged the ritual regicide of Amun, and ordered the defacing of Amun's temples throughout Egypt. Key features of Atenism included a ban on idols and other images of the Aten, with the exception of a rayed solar disc, in which the rays (commonly depicted ending in hands) appear to represent the unseen spirit of Aten. New temples were constructed, in which the Aten was worshipped in the open sunlight, rather than in dark temple enclosures, as the old gods had been.

Although idols were banned - even in people's homes - these were typically replaced by functionally equivalent representations of Akhenaten and his family venerating the Aten, and receiving the ankh (breath of life) from him. The radicalisation of Year 9 (including spelling Aten phonetically instead of using the rayed solar disc) may be due to a determination on the part of Akhenaten to enforce a probable misconception among the common people that Aten was really a type of sun god like Ra. Instead, the idea was reinforced that such representations were representations above all of concepts - of Aten's universal presence - not of physical beings or things.

The early stage of Atenism appears a kind of henotheism familiar in Egyptian religion, but the later form suggests a proto-monotheism.

Styles of art that flourished during this short period are markedly different from other Egyptian art, bearing a variety of affectations, from elongated heads to protruding stomachs, exaggerated ugliness and the beauty of Nefertiti. Significantly, and for the only time in the history of Egyptian royal art, Akhenaten's family was depicted in a decidedly naturalistic manner, and they are clearly shown displaying affection for each other. Greek influence may have resulted in some of the Amarna artistic characteristics.

Images of Akhenaten and Nefertiti usually depict the Aten prominently above that pair, with the hands of the Aten closest to each offering Ankhs. Unusually for new-kingdom art the Pharaoh and his Great Royal Wife are depicted as approximately equal in size, which together with Nefertiti's image used to decorate the lesser Aten temple at Amarna may suggest she also had a prominent official role in Aten worship.

Artistic representations of Akhenaten usually give him a strikingly feminine appearance, with slender limbs, a protruding belly and wide hips. Other leading figures of the Amarna period, both royal and otherwise, are also shown with some of these features, suggesting a possible religious connotation, especially as some sources suggest that private representations of Akhenaten, as opposed to official art, show him as quite normal. However, according to some controversial theories[who?], the strikingly unusual representations may have been due to non-religious factors - Akhenaten may actually been a woman masquerading as a man, which had been known to happen in Egyptian politics at least once before, or he may have had some intersex condition. It is also suggested by Bob Brier, in his book "The Murder of Tutankhamen", that the family suffered from Marfan's syndrome, which is known to cause elongated features, and that this may explain Akhenaten's appearance.

Crucial evidence about the latter stages of Akhenaten's reign was furnished by discovery of the so-called Amarna Letters. Believed to have been thrown away by scribes after being transferred to papyrus, the letters comprise a priceless cache of incoming clay message tablets sent from imperial outposts and foreign allies. The letters suggest that Akhenaten was obsessed with his new religion, and that his neglect of matters of state was causing disorder across the massive Egyptian empire. The governors and kings of subject domains wrote to beg for gold, and also complained of being snubbed and cheated. Also discovered were reports that a major plague pandemic was spreading across the ancient Near East. This pandemic appears to have claimed the life of Akhenaten's main wife (Nefertiti) and several of his six daughters, which may have contributed to a declining interest on the part of Akhenaten in governing effectively.

With Akhenaten's death, the Aten cult he had founded almost immediately fell out of favor due to pressures from the Priesthood of Amun. Tutankhaten, who succeeded him at age 8 (with Akhenaten's old vizier, Ay, as regent) changed his name to Tutankhamun in year 3 of his reign (1348 BC or 1331 BC) and abandoned Akhetaten, the city falling into ruin. Tutankhaten became the puppet king of the priests, thus the reason for his change of name. The priests threatened the unstable rulership of the child king and forced him to take various drastic actions which corrupted the written record of Egyptian succession and history, deleting the Amarna Revolution and Atenism. Temples Akhenaten had built, including the temple at Thebes, were disassembled, reused as a source of building materials and decorations for their own temples, and inscriptions to Aten defaced. Finally, Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, Tutankhamun, and Ay were removed from the official lists of Pharaohs, which instead reported that Amenhotep III was immediately succeeded by Horemheb.

Because of the monotheistic character of Atenism, a link to Judaism (and subsequently the monotheistic religions springing from it) has been suggested by various writers. For example, psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud assumed Akhenaten to be the pioneer of monotheistic religion and Moses as Akhenaten's follower in his book Moses and Monotheism.

The Egyptian conception of the universe centered on Ma'at, a word that encompasses several concepts in English, including "truth," "justice," and "order." It was the fixed, eternal order of the universe, both in the cosmos and in human society. It had existed since the creation of the world, and without it the world would lose its cohesion. In Egyptian belief, Ma'at was constantly under threat from the forces of disorder, so all of society was required to maintain it.

On the human level this meant that all members of society should cooperate and coexist; on the cosmic level it meant that all of the forces of nature - the gods - should continue to function in balance. This latter goal was central to Egyptian religion. The Egyptians sought to maintain Ma'at in the cosmos by sustaining the gods through offerings and by performing rituals which staved off disorder and perpetuated the cycles of nature.

The most important part of the Egyptian view of the cosmos was the conception of time, which was greatly concerned with the maintenance of Ma'at. Throughout the linear passage of time, a cyclical pattern recurred, in which Ma'at was renewed by periodic events which echoed the original creation. Among these events were the annual Nile flood and the succession from one king to another, but the most important was the daily journey of the sun god Ra.

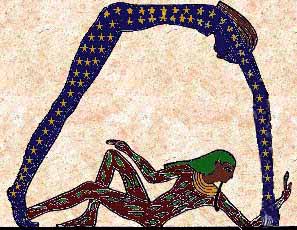

When envisioning the shape of the cosmos, the Egyptians saw the earth as a flat expanse of land, personified by the god Geb, over which arched the sky goddess Nut. The two were separated by Shu, the god of air. Beneath the earth lay a parallel underworld and undersky, and beyond the skies lay the infinite expanse of Nu, the chaos that had existed before creation. The Egyptians also believed in a place called the Duat, a mysterious region associated with death and rebirth, that may have lain in the underworld or in the sky. Each day, Ra traveled over the earth across the underside of the sky, and at night he passed through the Duat to be reborn at dawn.

In Egyptian belief, this cosmos was inhabited by three types of sentient beings. One was the gods; another was the spirits of deceased humans, who existed in the divine realm and possessed many of the gods' abilities. Living humans were the third category, and the most important among them was the pharaoh, who bridged the human and divine realms.

Egyptologists have long debated the degree to which the pharaoh was considered a god. It seems most likely that the Egyptians viewed royal authority itself as a divine force. Therefore, although the Egyptians recognized that the pharaoh was human and subject to human weakness, they simultaneously viewed him as a god, because the divine power of kingship was incarnate in him. He therefore acted as intermediary between Egypt's people and the gods. He was key to upholding Ma'at, both by maintaining justice and harmony in human society and by sustaining the gods with temples and offerings. For these reasons, he oversaw all state religious activity. However, the pharaoh's real-life influence and prestige could differ from that depicted in official writings and depictions, and beginning in the late New Kingdom his religious importance declined drastically.

The king was also associated with many specific deities. He was identified directly with Horus, who represented kingship itself, and he was seen as the son of Ra, who ruled and regulated nature as the pharaoh ruled and regulated society. By the New Kingdom he was also associated with Amun, the supreme force in the cosmos. Upon his death, the king became fully deified. In this state, he was directly identified with Ra, and was also associated with Osiris, god of death and rebirth and the mythological father of Horus. Many mortuary temples were dedicated to the worship of deceased pharaohs as gods.

The Egyptians had elaborate beliefs about death and the afterlife. They believed that humans possessed a ka, or life-force, which left the body at the point of death. In life, the ka received its sustenance from food and drink, so it was believed that, to endure after death, the ka must continue to receive offerings of food, whose spiritual essence it could still consume. Each person also had a ba, the set of spiritual characteristics unique to each individual. Unlike the ka, the ba remained attached to the body after death. Egyptian funeral rituals were intended to release the ba from the body so that it could move freely, and to rejoin it with the ka so that it could live on as an akh. However, it was also important that the body of the deceased be preserved, as the Egyptians believed that the ba returned to its body each night to receive new life, before emerging in the morning as an akh.

Originally, however, the Egyptians believed that only the pharaoh had a ba, and only he could become one with the gods; dead commoners passed into a dark, bleak realm that represented the opposite of life. The nobles received tombs and the resources for their upkeep as gifts from the king, and their ability to enter the afterlife was believed to be dependent on these royal favors. In early times the deceased pharaoh was believed to ascend to the sky and dwell among the stars. Over the course of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686-2181 BC), however, he came to be more closely associated with the daily rebirth of the sun god Ra and with the underworld ruler Osiris as those deities grew more important.

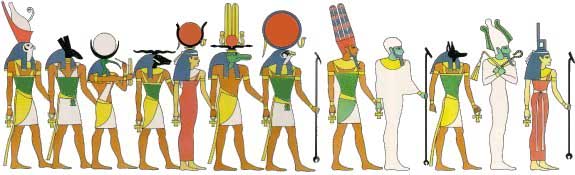

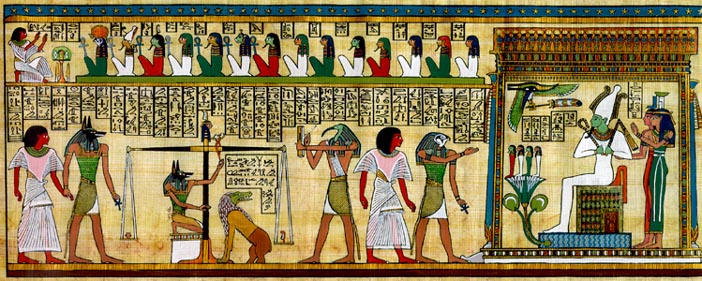

During the late Old Kingdom and the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181-2055 BC), the Egyptians gradually came to believe that possession of a ba and the possibility of a paradisiacal afterlife extended to everyone. In the fully developed afterlife beliefs of the New Kingdom, the soul had to avoid a variety of supernatural dangers in the Duat, before undergoing a final judgment known as the "Weighing of the Heart". In this judgment, the gods compared the actions of the deceased while alive (symbolized by the heart) to Ma'at, to determine whether he or she had behaved in accordance with Ma'at. If the deceased was judged worthy, his or her ka and ba were united into an akh.

Several beliefs coexisted about the akh's destination. Often the dead were said to dwell in the realm of Osiris, a lush and pleasant land in the underworld. The solar vision of the afterlife, in which the deceased soul traveled with Ra on his daily journey, was still primarily associated with royalty, but could extend to other people as well. Over the course of the Middle and New Kingdoms, the notion that the akh could also travel in the world of the living, and to some degree magically affect events there, became increasingly prevalent.

Egyptian myths were metaphorical stories intended to illustrate and explain the gods' actions and roles in nature. The details of the events they recounted could change to convey different symbolic perspectives on the mysterious divine events they described, so many myths exist in different and conflicting versions. Mythical narratives were rarely written in full, and more often texts only contain episodes from or allusions to a larger myth

Knowledge of Egyptian mythology, therefore, is derived mostly from hymns that detail the roles of specific deities, from ritual and magical texts which describe actions related to mythic events, and from funerary texts which mention the roles of many deities in the afterlife. Some information is also provided by allusions in secular texts. Finally, Greeks and Romans such as Plutarch recorded some of the extant myths late in Egyptian history.

Among the significant Egyptian myths were the creation myths. According to these stories, the world emerged as a dry space in the primordial ocean of chaos. Because the sun is essential to life on earth, the first rising of Ra marked the moment of this emergence. Different forms of the myth describe the process of creation in various ways: a transformation of the primordial god Atum into the elements that form the world, as the creative speech of the intellectual god Ptah, and as an act of the hidden power of Amun. Regardless of these variations, the act of creation represented the initial establishment of maat and the pattern for the subsequent cycles of time.

The most important of all Egyptian myths was the myth of Osiris and Isis. It tells of the divine ruler Osiris, who was murdered by his jealous brother Set, a god often associated with chaos. Osiris' sister and wife Isis resurrected him so that he could conceive an heir, Horus.

Osiris then entered the underworld and became the ruler of the dead. Once grown, Horus fought and defeated Set to become king himself. Set's association with chaos, and the identification of Osiris and Horus as the rightful rulers, provided a rationale for pharaonic succession and portrayed the pharaohs as the upholders of order. At the same time, Osiris' death and rebirth were related to the Egyptian agricultural cycle, in which crops grew in the wake of the Nile inundation, and provided a template for the resurrection of human souls after death.

Another important mythic motif was the journey of Ra through the Duat each night. In the course of this journey, Ra met with Osiris, who again acted as an agent of regeneration, so that his life was renewed. He also fought each night with Apep, a serpentine god representing chaos. The defeat of Apep and the meeting with Osiris ensured the rising of the sun the next morning, an event that represented rebirth and the victory of order over chaos.

The procedures for religious rituals were frequently written on papyri, which were used as instructions for those performing the ritual. These ritual texts were kept mainly in the temple libraries. Temples themselves are also inscribed with such texts, often accompanied by illustrations. Unlike the ritual papyri, these inscriptions were not intended as instructions, but were meant to symbolically perpetuate the rituals even if, in reality, people ceased to perform them. Magical texts likewise describe rituals, although these rituals were part of the spells used for specific goals in everyday life. Despite their mundane purpose, many of these texts also originated in temple libraries and later became disseminated among the general populace.

The Egyptians produced numerous prayers and hymns, written in the form of poetry. Hymns and prayers follow a similar structure and are distinguished mainly by the purposes they serve. Hymns were written to praise particular deities. Like ritual texts, they were written on papyri and on temple walls, and they were probably recited as part of the rituals they accompany in temple inscriptions.

Most are structured according to a set literary formula, designed to expound on the nature, aspects, and mythological functions of a given deity. They tend to speak more explicitly about fundamental theology than other Egyptian religious writings, and became particularly important in the New Kingdom, a period of particularly active theological discourse. Prayers follow the same general pattern as hymns, but address the relevant god in a more personal way, asking for blessings, help, or forgiveness for wrongdoing. Such prayers are rare before the New Kingdom, indicating that in earlier periods such direct personal interaction with a deity was not believed possible, or at least was less likely to be expressed in writing. They are known mainly from inscriptions on statues and stelae left in sacred sites as votive offerings.

Egyptian religion produced the temples and tombs which are ancient Egypt's most enduring monuments, but it also left many influences on other cultures. In pharaonic times many of its symbols, such as the sphinx and winged solar disk, spread widely across the Mediterranean and Near East, as did some of its deities, such as Bes. Some of these connections are difficult to trace. The Greek concept of Elysium may have derived from the Egyptian vision of the afterlife.

In late antiquity, the Christian conception of Hell was most likely influenced by some of the imagery of the Duat, and the iconography of Mary may have been influenced by that of Isis. Egyptian beliefs also influenced or gave rise to several esoteric belief systems developed by Greeks and Romans who saw Egypt as a source of mystic wisdom. Hermeticism, for instance, derived from the tradition of secret magical knowledge associated with Thoth.

Traces of ancient beliefs remained in Egyptian folk traditions into modern times, but its impact on modern societies greatly increased with the French Campaign in Egypt and Syria in 1798. As a result of it, Westerners began to study Egyptian beliefs firsthand, and Egyptian religious motifs were adopted into Western art. Egyptian religion has since had a significant impact on popular culture. Due to continued interest in Egyptian belief, in the late 20th century several new religious groups formed based on different reconstructions of ancient Egyptian religion.