One of the earliest advanced civilizations, Ancient Egypt, had a rich religious tradition which permeated every aspect of society. As in most early cultures, the patterns and behaviors of the sky led to the creation of a number of myths to explain the astronomical phenomena. For the Egyptians, the practice of astronomy went beyond legend. Huge temples and pyramids were built with specific astronomical orientations. Thus astronomy had both religious and practical purposes.

Creation and protection came from the gods. Today we associate these gods with Ancient Alien Theory and Reality as a Consciousness Hologram.

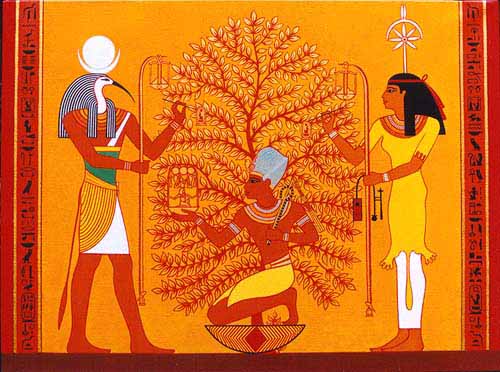

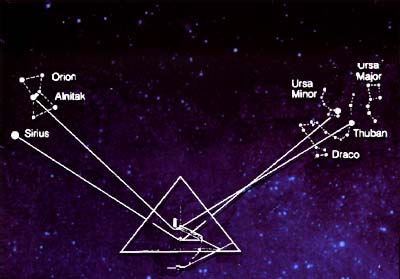

The Egyptian gods and goddesses were numerous, pictured in many paintings and murals with celestial alignments. Certain gods were seen in the constellations, and others were represented by actual astronomical bodies. The constellation Orion, for instance, represented Osiris, who was the god of death, rebirth, and the afterlife. The Belt Stars of Orion align with the three pyramids on the Giza Plateau.

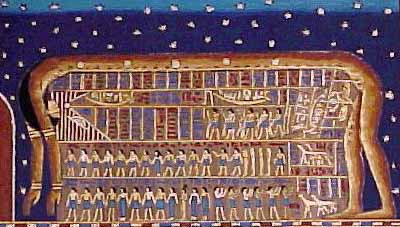

The Milky Way represented the sky goddess Nut giving birth to the sun god Ra.

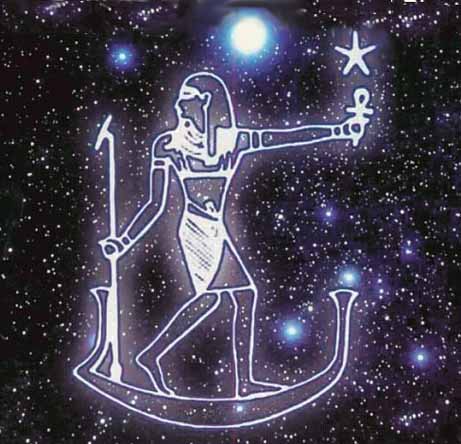

The stars in Egyptian mythology were represented by the goddess of writing, Seshat, while the Moon was either Thoth, the god of wisdom and writing, or Khons, a child moon god.

The horizon was extremely important to the Egyptians, since it was here that the Sun appeared and disappeared daily. A hymn to the Sun god Ra shows this reverance: 'O Ra! In thine egg, radiant in thy disk, shining forth from the horizon, swimming over the steel firmament.' The Sun itself was represented by several gods, depending on its position. A rising morning Sun was Horus, the divine child of Osiris and Isis. The noon Sun was Ra because of its incredible strength.

The evening Sun became Atum, the creator god who lifted Pharoahs from their tombs to the stars. The red color of the Sun at sunset was considered to be the blood from the Sun god as he died. After the Sun had set, it became Osiris, god of death and rebirth. In this way, night was associated with death and day with life or rebirth. This reflects the typical Egyptian idea of immortality.

The center of Egyptian civilization was the flooding of the Nile River every year at the same time and provided rich soil for agriculture. The Egyptian astronomers, who were actually priests, recognized that the flooding always occurred at the summer solstice, which was also when the bright star Sirius rose before the Sun. The priests were therefore able to predict the annual flooding, which made them quite powerful.

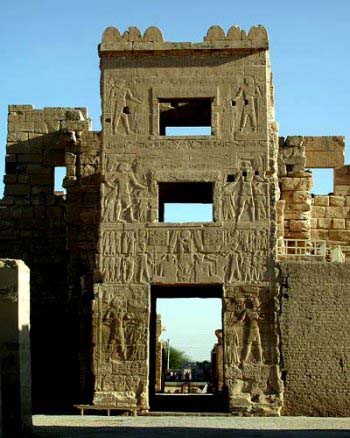

Many Egyptian buildings were built with an astronomical orientation. The temples and pyramids were constructed in relation to the stars, zodiac, and constellations. In different cities, the buildings had different orientations based on the specific religion of that place. For instance, some temples were constructed to align with a star that either rose or set at harvest or sowing time. Others were oriented toward the solstices or equinoxes. As early as 4000 B.C., temples were built so that sunlight entered a room at only one precise time of the year.

An alternative building method was to gradually narrow successive doors into a specific room, in order to concentrate the sunbeams onto a god's image on the wall. The designs sometimes became quite complex. At the temple of Medinet Habu, there are actually two buildings which are slightly off-kilter. It has been suggested that the second one was built when the altitude of the other temple's orientation stars changed over a long period of time.

The Egyptians were a practical people and this is reflected in their astronomy in contrast to Babylonia where the first astronomical texts were written in astrological terms. Even before Upper and Lower Egypt were unified in 3000 BCE, observations of the night sky had influenced the development of a religion in which many of its principal deities were heavenly bodies.

In Lower Egypt, priests built circular mud-brick walls with which to make a false horizon where they could mark the position of the sun as it rose at dawn, and then with a plumb-bob note the northern or southern turning points (solstices). This allowed them to discover that the sun disc, personified as Ra, took 365 days to travel from his birthplace at the winter solstice and back to it. Meanwhile in Upper Egypt a lunar calendar was being developed based on the behavior of the moon and the reappearance of Sirius in its heliacal rising after its annual absence of about 70 days.

After unification, problems with trying to work with two calendars (both depending upon constant observation) led to a merged, simplified civil calendar with twelve 30 day months, three seasons of four months each, plus an extra five days, giving a 365 year day but with no way of accounting for the extra quarter day each year. Day and night were split into 24 units, each personified by a deity.

A sundial found on Seti I's cenotaph with instructions for its use shows us that the daylight hours were at one time split into 10 units, with 12 hours for the night and an hour for the morning and evening twilights. However, by Seti I's time day and night were normally divided into 12 hours each, the length of which would vary according to the time of year.

Key to much of this was the motion of the sun god Ra and his annual movement along the horizon at sunrise. Out of Egyptian myths such as those around Ra and the sky goddess Nut came the development of the Egyptian calendar, time keeping, and even concepts of royalty.

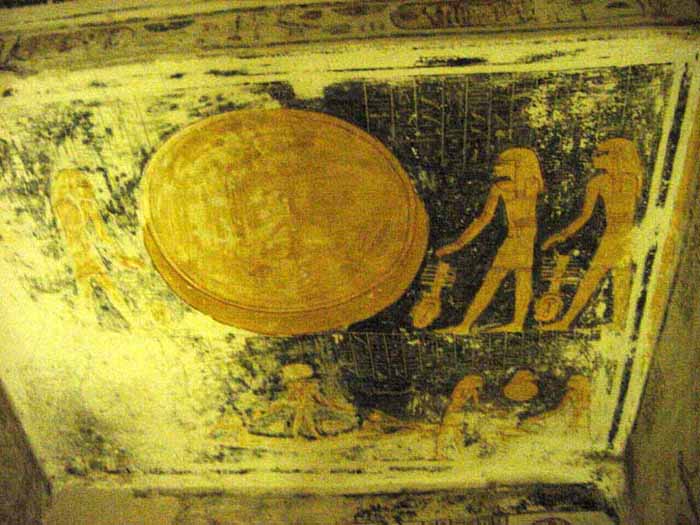

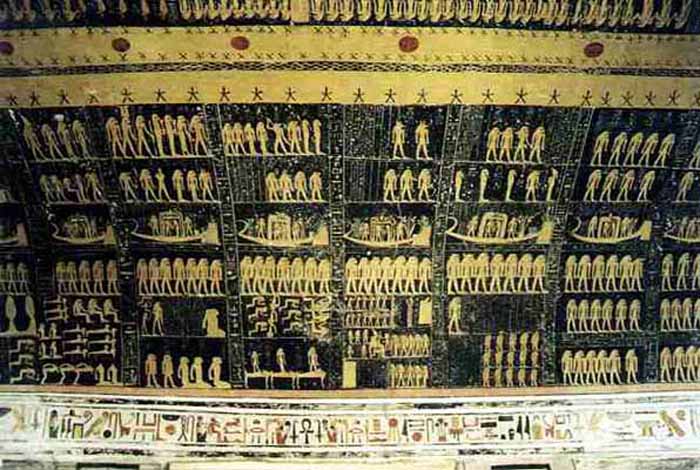

An astronomical ceiling in the burial chamber of Ramesses VI shows the sun being born from Nut in the morning, traveling along her body during the day and being swallowed at night.

During the Fifth Dynasty six kings built sun temples in honor of Ra. The temple complexes built by Niuserre at Abu Gurab and Userkaf at Abusir have been excavated and have astronomical alignments, and the roofs of some of the buildings could have been used by observers to view the stars, calculate the hours at night and predict the sunrise for religious festivals.

Claims have been made thatprecession of the equinoxes was known in Ancient Egypt prior to the time of Hipparchus. This has been disputed however on the grounds that pre-Hipparchus texts do not mention precession and that "it is only by cunning interpretation of ancient myths and images, which are ostensibly about something else, that precession can be discerned in them, aided by some pretty esoteric numerological speculation involving the 72 years that mark one degree of shift in the zodiacal system and any number of permutations by multiplication, division, and addition."

Note however that the observation that a stellar alignment has grown wrong does not necessarily mean that the Egyptians understood or even cared what was going on. For instance, from the Middle Kingdom on they used a table with entries for each month to tell the time of night from the passing of constellations: these went in error after a few centuries because of their calendar and precession, but were copied (with scribal errors) for long after they lost their practical usefulness or possibly the understanding of them.

Egyptian astronomy begins in prehistoric times, in the Predynastic Period. In the 5th millennium BCE, the stone circles at Nabta Playa may have made use of astronomical alignments. By the time the historical Dynastic Period began in the 3rd millennium BCE, the 365 day period of the Egyptian calendar was already in use, and the observation of stars was important in determining the annual flooding of the Nile. The Egyptian pyramids were carefully aligned towards the pole star, and the temple of Amun-Re at Karnak was aligned on the rising of the midwinter sun. Astronomy played a considerable part in fixing the dates of religious festivals and determining the hours of the night, and temple astrologers were especially adept at watching the stars and observing the conjunctions, phases, and risings of the Sun, Moon and planets.

In Ptolemaic Egypt, the Egyptian tradition merged with Greek astronomy and Babylonian astronomy, with the city of Alexandria in Lower Egypt becoming the centre of scientific activity across the Hellenistic world. Roman Egypt produced the greatest astronomer of the era, Ptolemy (90-168 CE). His works on astronomy, including the Almagest, became the most influential books in the history of Western astronomy. Following the Muslim conquest of Egypt, the region came to be dominated by Arabic culture and Islamic astronomy.

The astronomer Ibn Yunus (c. 950-1009) observed the sun's position for many years using a large astrolabe, and his observations on eclipses were still used centuries later. In 1006, Ali ibn Ridwan observed the SN 1006, a supernova regarded as the brightest steller event in recorded history, and left the most detailed description of it. In the 14th century, Najm al-Din al-Misri wrote a treatise describing over 100 different types of scientific and astronomical instruments, many of which he invented himself.

In the 20th century, Farouk El-Baz from Egypt worked for NASA and was involved in the first Moon landings with the Apollo program, where he assisted in the planning of scientific explorations of the Moon.

Egyptian astronomy begins in prehistoric times. The presence of stone circles at Nabta Playa dating from the 5th millennium BCE show the importance of astronomy to the religious life of ancient Egypt even in the prehistoric period. The annual flooding of the Nile meant that the heliacal risings, or first visible appearances of stars at dawn, was of special interest in determining when this might occur, and it is no surprise that the 365 day period of the Egyptian calendar was already in use at the beginning of Egyptian history. The constellation system used among the Egyptians also appears to have been essentially of native origin.

The precise orientation of the Egyptian pyramids affords a lasting demonstration of the high degree of technical skill in watching the heavens attained in the 3rd millennium BCE. It has been shown the Pyramids were aligned towards the pole star, which, because of the precession of the equinoxes, was at that time Thuban, a faint star in the constellation of Draco. Evaluation of the site of the temple of Amun-Re at Karnak, taking into account the change over time of the obliquity of the ecliptic, has shown that the Great Temple was aligned on the rising of the midwinter sun. The length of the corridor down which sunlight would travel would have limited illumination at other times of the year.

Astronomy played a considerable part in religious matters for fixing the dates of festivals and determining the hours of the night. The titles of several temple books are preserved recording the movements and phases of the sun, moon and stars. The rising of Sirius (Egyptian: Sopdet, Greek: Sothis) at the beginning of the inundation was a particularly important point to fix in the yearly calendar.

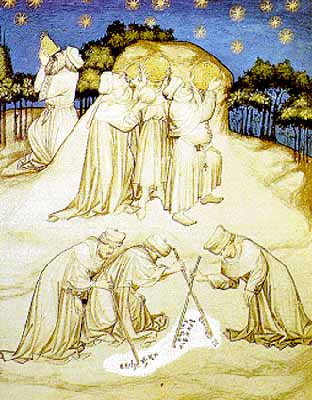

From the tables of stars on the ceiling of the tombs of Rameses VI and Rameses IX it seems that for fixing the hours of the night a man seated on the ground faced the Astrologer in such a position that the line of observation of the pole star passed over the middle of his head. On the different days of the year each hour was determined by a fixed star culminating or nearly culminating in it, and the position of these stars at the time is given in the tables as in the centre, on the left eye, on the right shoulder, etc. According to the texts, in founding or rebuilding temples the north axis was determined by the same apparatus, and we may conclude that it was the usual one for astronomical observations. In careful hands it might give results of a high degree of accuracy.

Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius (floruit AD 395-423) attributed the planetary theory where the Earth rotates on its axis and the interior planets Mercury and Venus revolve around the Sun which in turn revolves around the Earth, to the ancient Egyptians. He named it the "Egyptian System," and stated that "it did not escape the skill of the Egyptians," though there is no other evidence it was known in ancient Egypt.

The Astrologer's instruments (horologium and palm) are a plumb line and sighting instrument. They have been identified with two inscribed objects in the Berlin Museum; a short handle from which a plumb line was hung, and a palm branch with a sight-slit in the broader end. The latter was held close to the eye, the former in the other hand, perhaps at arms length. The "Hermetic" books which Clement refers to are the Egyptian theological texts, which probably have nothing to do with Hellenistic Hermetism.

Following Alexander the Great's conquests and the foundation of Ptolemaic Egypt, the native Egyptian tradition of astronomy had merged with Greek astronomy as well as Babylonian astronomy. The city of Alexandria in Lower Egypt became the centre of scientific activity throughout the Hellenistic civilization.

The greatest Alexandrian astronomer of this era was the Greek, Eratosthenes (c. 276-195 BCE), who calculated the size of the Earth, providing an estimate for the circumference of the Earth.

Following the Roman conquest of Egypt, the region once again became the centre of scientific activity throughout the Roman Empire. The greatest astronomer of this era was the Hellenized Egyptian, Ptolemy (90-168 CE).

Originating from the Thebaid region of Upper Egypt, he worked at Alexandria and wrote works on astronomy including the Almagest, the Planetary Hypotheses, and the Tetrabiblos, as well as the Handy Tables, the Canobic Inscription, and other minor works. The Almagest is one of the most influential books in the history of Western astronomy. In this book, Ptolemy explained how to predict the behavior of the planets with the introduction of a new mathematical tool, the equant.

A few mathematicians of late Antiquity wrote commentaries on the Almagest, including Pappus of Alexandria as well as Theon of Alexandria and his daughter Hypatia. Ptolemaic astronomy became standard in medieval western European and Islamic astronomy until it was displaced by Maraghan, heliocentric and Tychonic systems by the 16th century.

Following the Muslim conquest of Egypt, the region came to be dominated by Arabic culture. It was ruled by the Rashidun, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates up until the 10th century, when the Fatimids founded their own Caliphate centered around the city of Cairo in Egypt. The region once again became a centre of scientific activity, competing with Baghdad for intellectual dominance in the medieval Islamic world. By the 13th century, the city of Cairo eventually overtook Baghdad as the intellectual center of the Islamic world.

Ibn Yunus (c. 950-1009) observed more than 10,000 entries for the sun's position for many years using a large astrolabe with a diameter of nearly 1.4 meters. His observations on eclipses were still used centuries later in Simon Newcomb's investigations on the motion of the moon, while his other observations inspired Laplace's Obliquity of the Ecliptic and Inequalities of Jupiter and Saturn.

In 1006, Ali ibn Ridwan observed the supernova of 1006, regarded as the brightest stellar event in recorded history, and left the most detailed description of the temporary star. He says that the object was two to three times as large as the disc of Venus and about one-quarter the brightness of the Moon, and that the star was low on the southern horizon.

The astrolabic quadrant was invented in Egypt in the 11th century or 12th century, and later known in Europe as the "Quadrans Vetus" (Old Quadrant).

In 14th century Egypt, Najm al-Din al-Misri (c. 1325) wrote a treatise describing over 100 different types of scientific and astronomical instruments, many of which he invented himself.

In the 20th century, Farouk El-Baz from Egypt worked for NASA and was involved in the first Moon landings with the Apollo program, where he was secretary of the Landing Site Selection Committee, Principal Investigator of Visual Observations and Photography, chairman of the Astronaut Training Group, and assisted in the planning of scientific explorations of the Moon, including the selection of landing sites for the Apollo missions and the training of astronauts in lunar observations and photography.