The earliest Roman art is generally associated with the overthrow of the Etruscan kings and the establishment of the Republic in 509 BC. Roman art is traditionally divided into two main periods, art of the Republic and art of the Roman Empire (from 27 BC on), with subdivisions corresponding to the major emperors or imperial dynasties.

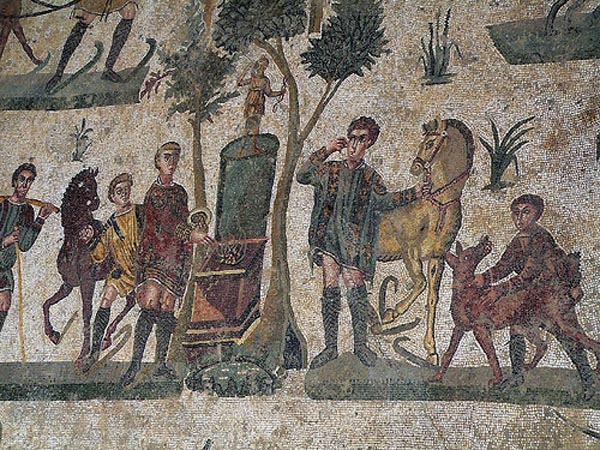

Roman art includes architecture, painting, sculpture and mosaic work. Luxury objects in metal-work, gem engraving, ivory carvings, and glass, are sometimes considered in modern terms to be minor forms of Roman art, although this would not necessarily have been the case for contemporaries.

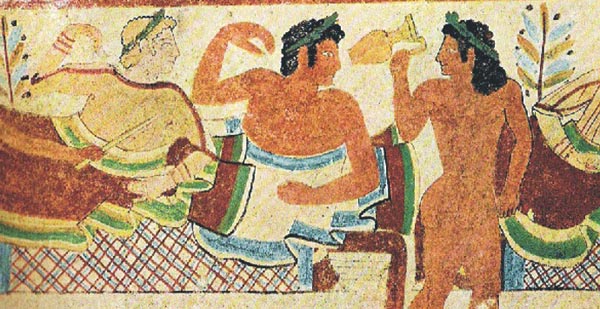

When the Republic was founded, the term Roman art was virtually synonymous with the art of the city of Rome, which still bore the stamp of its Etruscan art; during the last two centuries, notably that of Greece, Roman art shook off its dependence on Etruscan art; during the last two centuries before Christ a distinctive Roman manner of building, sculpting, and painting emerged. Never-the-less, because of the extraordinary geographical extent of the Roman Empire and the number of diverse populations encompassed within its boundaries, the art and architecture of the Romans was always eclectic and is characterized by varying styles attributable to differing regional tastes and the diverse preferences of a wide range of patrons.

Roman art is not just the art of the emperors, senators, and aristocracy, but of all the peoples of Rome's vast empire, including middle-class businessmen, freedmen, slaves, and soldiers in Italy and the provinces. Curiously, although examples of Roman sculptures, paintings, buildings, and decorative arts survive in great numbers, few names of Roman artists and architects are recorded. In general, Roman monuments were designed to serve the needs of their patrons rather than to express the artistic temperaments of their makers.

While the traditional view of Roman artists is that they often borrowed from, and copied Greek precedents (much of the Greek sculpture known today is in the form of Roman marble copies), more recent analysis has indicated that Roman art is a highly creative pastiche relying heavily on Greek models but also encompassing Etruscan, native Italic, and even Egyptian visual culture. Stylistic eclecticism and practical application are the hallmarks of much Roman art.

Pliny, Ancient Rome's most important historian concerning the arts, recorded that nearly all the forms of art - sculpture, landscape, portrait painting, even genre painting - were advanced in Greek times, and in some cases, more advanced than in Rome. Though very little remains of Greek wall art and portraiture, certainly Greek sculpture and vase painting bears this out. These forms were not likely surpassed by Roman artists in fineness of design or execution. As another example of the lost "Golden Age", he singled out Peiraikos, whose artistry is surpassed by only a very few. He painted barbershops and shoemakers' stalls, donkeys, vegetables, and such, and for that reason came to be called the 'painter of vulgar subjects'; yet these works are altogether delightful, and they were sold at higher prices than the greatest paintings of many other artists. The adjective "vulgar" is used here in its original meaning, which means "common".

The Greek antecedents of Roman art were legendary. In the mid-5th century BC., the most famous Greek artists were Polygnotos, noted for his wall murals, and Apollodoros, the originator of chiaroscuro. The development of realistic technique is credited to Zeuxis and Parrhasius, who according to ancient Greek legend, are said to have once competed in a bravura display of their talents, history's earliest descriptions of trompe l'oeil painting. In sculpture, Skopas, Praxiteles, Phidias, and Lysippos were the foremost sculptors. It appears that Roman artists had much Ancient Greek art to copy from, as trade in art was brisk throughout the empire, and much of the Greek artistic heritage found its way into Roman art through books and teaching. Ancient Greek treatises on the arts are known to have existed in Roman times though are now lost. Many Roman artists came from Greek colonies and provinces.

The high number of Roman copies of Greek art also speaks of the esteem Roman artists had for Greek art, and perhaps of its rarer and higher quality. Many of the art forms and methods used by the Romans - such as high and low relief, free-standing sculpture, bronze casting, vase art, mosaic, cameo, coin art, fine jewelry and metalwork, funerary sculpture, perspective drawing, caricature, genre and portrait painting, landscape painting, architectural sculpture, and trompe l'oeil painting - all were developed or refined by Ancient Greek artists. One exception is the Greek bust, which did not include the shoulders.

The traditional head-and-shoulders bust may have been an Etruscan or early Roman form. Virtually every artistic technique and method used by Renaissance artists 1,900 year later, had been demonstrated by Ancient Greek artists, with the notable exceptions of oil colors and mathematically accurate perspective. Where Greek artists were highly revered in their society, most Roman artists were anonymous and considered tradesmen.

There is no recording, as in Ancient Greece, of the great masters of Roman art, and practically no signed works. Where Greeks worshipped the aesthetic qualities of great art and wrote extensively on artistic theory, Roman art was more decorative and indicative of status and wealth, and apparently not the subject of scholars or philosophers.

Owing in part to the fact that the Roman cities were far larger than the Greek city-states in power and population, and generally less provincial, art in Ancient Rome took on a wider, and sometimes more utilitarian, purpose. Roman culture assimilated many cultures and was for the most part tolerant of the ways of conquered peoples.

Roman art was commissioned, displayed, and owned in far greater quantities, and adapted to more uses than in Greek times. Wealthy Romans were more materialistic; they decorated their walls with art, their home with decorative objects, and themselves with fine jewelry.

In the Christian era of the late Empire, from 350-500 CE, wall painting, mosaic ceiling and floor work, and funerary sculpture thrived, while full-sized sculpture in the round and panel painting died out, most likely for religious reasons.

When Constantine moved the capital of the empire to Byzantium (renamed Constantinople), Roman art incorporated Eastern influences to produce the Byzantine style of the late empire. When Rome was sacked in the 5th century, artisans moved to and found work in the Eastern capital. The Church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople employed nearly 10,000 workmen and artisans, in a final burst of Roman art under Emperor Justinian (527-565 AD), who also ordered the creation of the famous mosaics of Ravenna. Roman styles and even pagan oman subjects continued, however, for centuries, often in Christian guise.

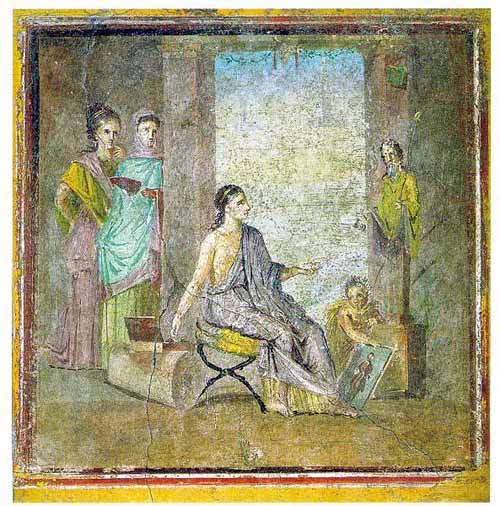

Pompeian painter with painted statue and framed painting Pompeii

Our knowledge of Ancient Roman painting relies in large part on the preservation of artifacts from Pompeii and Herculaneum, and particularly the Pompeian mural painting, which was preserved after the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. Nothing remains of the Greek paintings imported to Rome during the 4th and 5th centuries, or of the painting on wood done in Italy during that period.

In sum, the range of samples is confined to only about 200 years out of the about 900 years of Roman history, and of provincial and decorative painting. Most of this wall painting was done using the secco (dry) method, but some fresco paintings also existed in Roman times. There is evidence from mosaics and a few inscriptions that some Roman paintings were adaptations or copies of earlier Greek works. However, adding to the confusion is the fact that inscriptions may be recording the names of immigrant Greek artists from Roman times, not from Ancient Greek originals that were copied.

Roman painting provides a wide variety of themes: animals, still life, scenes from everyday life, portraits, and some mythological subjects. During the Hellenistic period, it evoked the pleasures of the countryside and represented scenes of shepherds, herds, rustic temples, rural mountainous landscapes and country houses.

Erotic scenes are also relatively common. In the late empire, after 200AD, early Christian themes mixed with pagan imagery survive on catacomb walls.

Roman mural painting is generally distinguished by four periods, as originally described by the German archaeologist August Mau and dealt with in more detail at Pompeian Styles.

The main innovation of Roman painting compared to Greek art was the development of landscapes, in particular incorporating techniques of perspective, though true mathematical perspective developed 1,515 years later.

Surface textures, shading, and coloration are well applied but scale and spatial depth was still not rendered accurately. Some landscapes were pure scenes of nature, particularly gardens with flowers and trees, while others were architectural vistas depicting urban buildings.

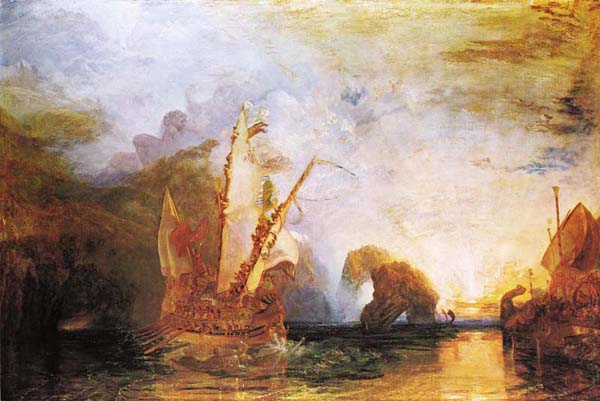

Other landscapes show episodes from mythology,

the most famous demonstrating scenes from the Odyssey.

Roman still life subjects are often placed in illusionistic niches or shelves and depict a variety of everyday objects including fruit, live and dead animals, seafood, and shells. Examples of the theme of the glass jar filled with water were skillfully painted and later served as models for the same subject often painted during the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

Woman in Mosaic

Roman fresco, Pompeii, Aphrodite

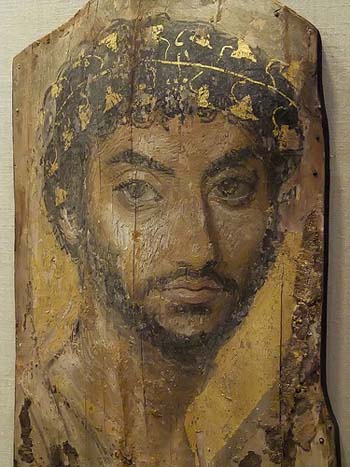

The portraits were attached to burial mummies at the face, from which almost all have now been detached. They usually depict a single person, showing the head, or head and upper chest, viewed frontally. The background is always monochrome, sometimes with decorative elements.

In terms of artistic tradition, the images clearly derive more from Greco-Roman traditions than Egyptian ones. They are remarkably realistic, though variable in artistic quality, and may indicate the similar art which was widespread elsewhere but did not survive. A few portraits painted on glass and medals from the later empire have survived, as have coin portraits, some of which are considered very realistic as well.

In Greece and Rome, wall painting was not considered as high art. The most prestigious form of art besides sculpture was panel painting, i.e. tempera or encaustic painting on wooden panels. Unfortunately, since wood is a perishable material, only a very few examples of such paintings have survived, namely the Severan Tondo from circa 200 AD, a very routine official portrait from some provincial government office, and the well-known Fayum mummy portraits, all from Roman Egypt, and almost certainly not of the highest contemporary quality.

Roman genre scenes generally depict Romans at leisure and include gambling, music and sexual encounters. Some scenes depict gods and goddesses at leisure.

Ancient Roman pottery was not a luxury product, but a vast production of "fine wares" in terra sigillata were decorated with reliefs that reflected the latest taste, and provided a large group in society with stylish objects at what was evidently an affordable price. Roman coins were an important means of propaganda, and have survived in enormous numbers. Other perishable forms of art have not survived at all.

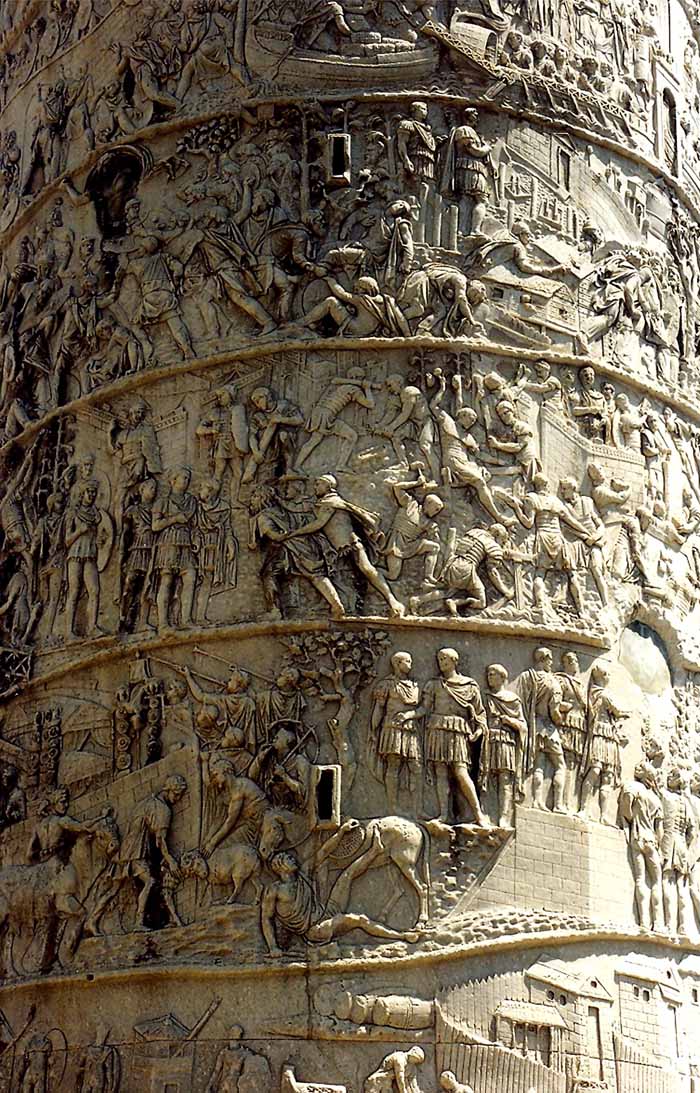

From the 3rd century BC, a specific genre known as Triumphal Paintings appeared, as indicated by Pliny (XXXV, 22). These were paintings which showed triumphal entries after military victories, represented episodes from the war, and conquered regions and cities. Summary maps were drawn to highlight key points of the campaign. These paintings have disappeared, but they likely influenced the composition of the historical reliefs carved on military sarcophagi, the Arch of Titus, and Trajan's Column. This evidence underscores the significance of landscape painting, which sometimes tended towards being perspective plans.

This episode is difficult to pinpoint. One of Ranuccio's hypotheses is that it refers to a victory of the consul Fabius Maximus Rullianus during the second war against Samnites in 326 BC. The presentation of the figures with sizes proportional to their importance is typically Roman, and finds itself in plebeian reliefs. This painting is in the infancy of triumphal painting, and would have been accomplished by the beginning of the 3rd century BC to decorate the tomb.

Traditional Roman sculpture is divided into five categories: portraiture, historical relief, funerary reliefs, sarcophagi, and copies of ancient Greek works.

Roman sculpture was heavily influenced by Greek examples, in particular their bronzes. It is only thanks to some Roman copies that a knowledge of Greek originals is preserved. One example of this is at the British Museum, where an intact 2nd century AD. Roman copy of a statue of Venus is displayed, while a similar original 500 BC. Greek statue at the Louvre is missing her arms.

Contrary to the belief of early archaeologists, many of these sculptures were large polychrome terra-cotta images, such as the Apollo of Veii (Villa Givlia, Rome), but the painted surface of many of them has worn away with time. Romans were nearly unique in the mixtures of materials (e.g. marble and porphyry) used both for painting and sculptures themselves, largely due to cost.

Portrait sculpture from the Republican era tends to be somewhat more modest, realistic, and natural compared to early Imperial works. A typical work might be one like the standing figure "A Roman Patrician with Busts of His Ancestors" (c. 30 BC.)

By the imperial age, though they were often realistic depictions of human anatomy, portrait sculpture of Roman emperors were often used for propaganda purposes and included ideological messages in the pose, accoutrements, or costume of the figure. Since most emperors from Augustus on were deified, some images are somewhat idealized. The Romans also depicted warriors and heroic adventures, in the spirit of the Greeks who came before them. Portrait sculptures were more commonly found.

While Greek sculptors traditionally illustrated military exploits through the use of mythological allegory, the Romans used a more documentary style. Roman reliefs of battle scenes, like those on the Column of Trajan, were created for the glorification of Roman might, but also provide first-hand representation of military costumes and military equipment.

Trajan's column records the various Dacian wars conducted by Trajan in what is modern day Romania. It is the foremost example of Roman historical relief and one of the great artistic treasures of the ancient world. This unprecedented achievement, over 650 foot of spiraling length, presents not just realistically rendered individuals (over 2,500 of them), but landscapes, animals, ships, and other elements in a continuous visual history - in effect an ancient precursor of a documentary movie. It survived destruction when it was adapted as a base for Christian sculpture. During the Christian era after 300 AD, the decoration of door panels and sarcophagi continued but full-sized sculpture died out and did not appear to be an important element in early churches.

Roman Architecture