An obelisk (from Greek "spit, nail, pointed pillar") is a tall, narrow, four-sided, tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape at the top. Ancient obelisks were often monolithic - whereas most modern obelisks are made of several stones and can have interior spaces. The term stele (plural: stelae) is generally used for other monumental standing inscribed sculpted stones. Because of the Enlightenment-era association of Egypt with mortuary arts, obelisks became associated with timelessness and memorialization. There are smaller obelisks or similar forms to be found in European, Asian, and American cemeteries or as World War I memorials in rural Australian towns.

The TV series Ancient Aliens is forever in search of physical evidence about the human-extraterrestrial experiment when ancient astronauts allegedly came to Earth to seed a root race leaving behind physical evidence of their presence as enigmatic clues to the mysteries of creation.

Among them we find inscribed obelisk-style monuments that some believe - when activated - were used for communication and as power sources.

Alien obelisks allegedly communicated with - each other, other extraterrestrial objects on the planet, Earth's Grid, as well as UFOs above and/or below the planet.

At some point in history they may have been power sources to keep the simulation of reality programmed and running at the physical level.

As an inscribed monument at this juncture of the human journey - unless an obelisk has discernible carvings that speak to end times - it's just an edifice belonging to the past much like other megaliths across the planet that tell story of the journey of humanity in his various iterations.

On Feb 3, 2023 - "Ancient Aliens" featured an episode called "The Power of the Obelisks". Tagline: The towering obelisks of ancient Egypt weigh hundreds of tons. Each was perfectly carved from a single granite rock. While mainstream scholars identify them as monuments to the pharaohs, Ancient Astronaut Theorists suggest they may have served a technological purpose - powering technology that allowed for communication with the gods who came from the stars.

In Egyptian mythology, the obelisk symbolized the Sun Gsod Ra, and during the religious reformation of Akhenaten it was said to have been a petrified ray of the Aten, the sundisk.

Symbolism: The obelisk is a solar symbol of regeneration and creation, and it symbolizes the Benben Stone - associated with the top stone of a pyramid, which is called a pyramid's pyramidion (or benbenet). Benben represents the first mound or stone to arise from the primordial waters at the creation of the world

Obelisks were prominent in the architecture of the ancient Egyptians, who placed them in pairs at the entrance of temples. The word "obelisk" as used in English today is of Greek rather than Egyptian origin because Herodotus, the Greek traveler, was one of the first classical writers to describe the objects.

Twenty-nine ancient Egyptian obelisks are known to have survived, plus the "Unfinished Obelisk" found partly hewn from its quarry at Aswan. These obelisks are now dispersed around the world, and less than half of them remain in Egypt. The obelisks can be found in the following locations:

Egypt - 9 - List of Egyptian Obelisks

Pharaoh Tuthmosis I, Karnak Temple, Luxor

Pharaoh Ramses II, Luxor Temple

Pharaoh Hatshepsut, Karnak Temple, Luxor

Pharaoh Senusret I, Al-Masalla area of Al-Matariyyah district in Heliopolis, Cairo

Pharaoh Ramses III, Luxor Museum

Pharaoh Ramses II, Gezira Island, Cairo, 20.4 m

Pharaoh Ramses II, Cairo International Airport, 16.97 m

Pharaoh Seti II, Karnak Temple, Luxor, 7 m

Pharaoh Senusret I, Faiyum (ancient site of Crocodilopolis), 12.9 m

France - 1

'Propaganda' praising Ramesses II discovered on famous 3,300-year-old Egyptian obelisk in Paris, Egyptologist claims Live Science - May 2, 2025

Israel - 1

Caesarea obelisk

Italy - 18 (includes the only one located in the Vatican City)

14 in Rome (see Obelisks in Rome)

Piazza del Duomo, Catania (Sicily)

Boboli Gardens (Florence)

Urbino

Poland - 1

Ramses II, Poznan Archaeological Museum, Poznan (on loan from Agyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, Berlin)

Turkey - 1

Pharaoh Tuthmosis III, in Square of Horses, Istanbul

United Kingdom - 4

Pharaoh Tuthmosis III, "Cleopatra's Needle", on Victoria Embankment, London

Pharaoh Amenhotep II, in the Oriental Museum, University of Durham

Pharaoh Ptolemy IX, Philae obelisk, at Kingston Lacy, near Wimborne Minster, Dorset

Pharaoh Nectanebo II, British Museum, London (pair of obelisks)

United States - 1

Pharaoh Tuthmosis III, "Cleopatra's Needle", in Central Park, New York

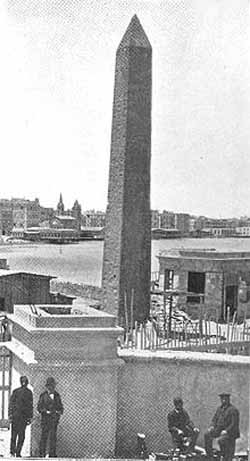

Cleopatra's Needles is the popular name for each of three Ancient Egyptian obelisks re-erected in London, Paris, and New York City during the nineteenth century. The London and New York ones are a pair, while the Paris one comes from a different original site where its twin remains. Although the needles are genuine Ancient Egyptian obelisks, they are somewhat misnamed as they have no particular connection with Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt, and were already over a thousand years old in her lifetime. The Paris "needle" was the first to be moved and re-erected, and the first to acquire the nickname.

The pair are made of red granite, stand about 21 metres (68 ft) high, weigh about 224 tons and are inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyphs. They were originally erected in the Egyptian city of Heliopolis on the orders of Thutmose III, around 1450 BC. The material of which they were cut is granite, brought from the quarries of Aswan, near the first cataract of the Nile. The inscriptions were added about 200 years later by Ramesses II to commemorate his military victories. The obelisks were moved to Alexandria and set up in the Caesareum - a temple built by Cleopatra in honor of Mark Antony - by the Romans in 12 BC, during the reign of Augustus, but were toppled some time later. This had the fortuitous effect of burying their faces and so preserving most of the hieroglyphs from the effects of weathering.

Location: Central Park, New York, USA

Pharaoh: Tuthmosis III (reigned 1504-1450 B.C.)

Height: 70 feet

Weight: 193 tons

The New York needle, Pompey's Pillar, was erected in Central Park on February 22, 1881. It was secured in May 1877 by judge Elbert E. Farman, the then-United States Consul General at Cairo, as a gift from Khedive for the United States remaining a friendly neutral as the European powers-France and Britain-maneuvered to secure political control of the Egyptian Government.

The original idea to secure an Egyptian obelisk for New York City came out of the March 1877 New York City newspaper accounts of the transportation of the London obelisk. If Paris had one and London was to get one, why should not New York get one?

The newspapers mistakenly attributed to a Mr. John Dixon the 1869 proposal of the Khedive of Egypt to give the United States the remaining Alexandria obelisk as a gift for increased trade. Mr. Dixon was the 1877 contractor who arranged the transport of the London obelisk and denied the newspaper accounts.

In March 1877 and based on the newspaper accounts, Mr. Henry G. Stebbins, then Commissioner of the Department of Public Parks of the City of New York, undertook to secure the funding to transport the obelisk to New York. When the railroad magnate William H. Vanderbilt was asked to head the subscription, he generously offered to finance the project with a donation of over $100,000. Mr. Stebbins then sent two acceptance letters to the Khedive through the Department of State which forwarded them to Judge Farman in Cairo. Realizing that the New York accounts were false and that he might be able to secure one of the two remaining upright obelisks - either the mate to the Paris obelisk in Luxor or the London mate in Alexandria; Judge Farman formally asked the Khedive in March 1877 and by May 1877 he had secured the gift in writing.

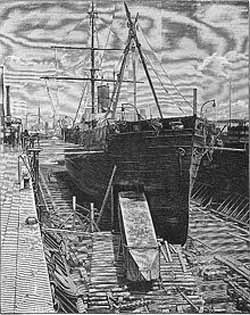

The formidable task of moving the Obelisk from Alexandria to New York was given to Henry Honychurch Gorringe, a lieutenant commander on leave from the U.S. Navy. Cleopatra's Needle is a 240-ton, 68 foot 10 inch, single shaft of red granite from the AssuČn (formerly Syene) Quarries at the 1st Cataract of the Nile. The 220-ton granite needle was first shifted from vertical to horizontal, nearly crashing to ground in the process, then put into the hold of the steamship Dessoug which set sail 12 June 1880.

It took 32 horses hitched in 16 pairs to bring it from the banks of the Hudson River to Staten Island, finally arriving on 20 July 1880. The final leg of the journey was made across a specially built trestle bridge from Fifth Avenue to its new home on Greywacke Knoll, just across the drive from the then recently built Metropolitan Museum of Arthieroglyphics.

Most Worshipful Jesse B. Anthony, Grand Master of Masons in the State of New York, presided as the cornerstone for the obelisk was laid in place with full Masonic ceremony on October 2, 1880. Over nine thousand Masons paraded up Fifth Avenue from 14th Street to 82nd Street and it was estimated that over fifty thousand spectators lined the parade route. The benediction was presented by R.W. Louis C. Gerstein.

The surface of the stone is heavily weathered, nearly masking the rows of hieroglyphics engraved on all sides. Photographs taken near the time the obelisk was erected in the park show that the inscriptions or hieroglyphics, as depicted below with translation, were still quite legible and date first from Thutmosis III (1479-1425 BCE) and then nearly 300 years later, Ramesses II the Great (1279-1213 BCE). The stone had stood in the clear dry Egyptian desert air for nearly 3000 years and had undergone little weathering. In a little more than a century in the climate of New York City, pollution and acid rain have heavily pitted its surfaces.

of Al-Matariyyah district in Heliopolis, Cairo

The earliest temple obelisk still in its original position is the 20.7 m / 68 ft high 120 tons red granite Obelisk of Senusret I of the XIIth Dynasty at Al-Matariyyah part of Heliopolis. The obelisk symbolized the sun god Ra, and during the brief religious reformation of Akhenaten was said to be a petrified ray of the Aten, the sundisk. It was also thought that the god existed within the structure.

It is hypothesized by New York University Egyptologist Patricia Blackwell Gary and Astronomy senior editor Richard Talcott that the shapes of the ancient Egyptian pyramid and obelisk were derived from natural phenomena associated with the sun (the sun-god Ra being the Egyptians' greatest deity). The pyramid and obelisk might have been inspired by previously overlooked astronomical phenomena connected with sunrise and sunset: the zodiacal light and sun pillars respectively.

The city of Rome harbors thirteen ancient obelisks, the most in the world. There are eight ancient Egyptian and five ancient Roman obelisks in Rome, together with a number of more modern obelisks; there was also until 2005 an ancient Ethiopian obelisk in Rome.

The Romans used special heavy cargo carriers called obelisk ships to transport the monuments down the Nile to Alexandria and from there across the Mediterranean Sea to Rome. On site, large Roman cranes were employed to erect the monoliths. The Ancient Romans were strongly influenced by the obelisk form, to the extent that there are now more than twice as many obelisks standing in Rome as remain in Egypt. All fell after the Roman period except for the Vatican obelisk and were re-erected in different locations.

The tallest Egyptian obelisk is in the square in front of the Lateran Basilica in Rome at 105.6 feet tall and a weight of 455 tons

Not all the Egyptian obelisks erected in the Roman Empire were set up at the city of Rome. Herod the Great imitated his Roman patrons and set up a red granite Egyptian obelisk in the hippodrome of his new city Caesarea in northern Judea. This one is about 40 feet tall and weighs about 100 tons. It was discovered by archaeologists and has been re-erected at its former site.

In Constantinople, the Eastern Emperor Theodosius shipped an obelisk in AD 390 and had it set up in his hippodrome, where it has weathered Crusaders and Seljuks and stands in the Hippodrome square in modern Istanbul. This one stood 95 feet tall, weighing 380 tons. Its lower half reputedly also once stood in Istanbul but is now lost. The Istanbul obelisk is 65 feet tall.

Rome is the obelisk capital of the world. The most prominent is the 25.5 m/83.6 ft high 331 ton obelisk at Saint Peter's Square in Rome. The obelisk had stood since AD 37 on its site on the wall of the Circus of Nero, flanking St Peter's Basilica.

Re-erecting the obelisk had daunted even Michelangelo, but Sixtus V was determined to erect it in front of St Peter's, of which the nave was yet to be built. He had a full-sized wooden mock-up erected within months of his election. Domenico Fontana, the assistant of Giacomo Della Porta in the Basilica's construction, presented the Pope with a little model crane of wood and a heavy little obelisk of lead, which Sixtus himself was able to raise by turning a little winch with his finger. Fontana was given the project.

The obelisk, half-buried in the debris of the ages, was first excavated as it stood; then it took from April 30 to May 17, 1586 to move it on rollers to the Piazza: it required nearly 1000 men, 140 carthorses, 47 cranes. The re-erection, scheduled for September 14, the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross, was watched by a large crowd. It was a famous feat of engineering, which made the reputation of Fontana, who detailed it in a book illustrated with copperplate etchings, Della Trasportatione dell'Obelisco Vaticano et delle Fabriche di Nostro Signore Papa Sisto V (1590), which itself set a new standard in communicating technical information and influenced subsequent architectural publications by its meticulous precision.

Before being re-erected the obelisk was exorcised. It is said that Fontana had teams of relay horses to make his getaway if the enterprise failed. When Carlo Maderno came to build the Basilica's nave, he had to put the slightest kink in its axis, to line it precisely with the obelisk.

An obelisk stands in front of the church of Trinita dei Monti, at the head of the Spanish Steps. Another obelisk in Rome is sculpted as carried on the back of an elephant. Rome lost one of its obelisks, which had decorated the temple of Isis, where it was uncovered in the 16th century. The Medici claimed it for the Villa Medici, but in 1790 they moved it to the Boboli Gardens attached to the Palazzo Pitti in Florence, and left a replica in its stead.

Several more Egyptian obelisks have been re-erected elsewhere. The best-known examples outside Rome are the pair of 21 m/68 ft Cleopatra's Needles in London(69 feet 187 tons) and New York City(70 feet 193 tons) and the 23 m/75 ft 227 ton obelisk at the Place de la Concorde in Paris.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_obelisks_in_Rome

Obelisk type monuments are also known from the Assyrian civilization, where they were erected as public monuments that commemorated the achievements of the Assyrian king. The British Museum possesses three Assyrian obelisks:

White Obelisk on display in the British Museum

White Obelisk of Ashurnasirpal I was discovered by Iraqi archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam in 1853 at Nineveh. The obelisk was erected by either Ashurnasirpal I (1050-1031 BC) or Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BC).

According to the excavator's report, it was found about 60 metres to the northeast of Sennacherib's palace at a depth of about 5 metres below the surface of the mound. It was then shipped to London via Bombay on HMS Akbar in March 1854, arriving in the British capital in February 1855, where it was immediately deposited in the national collection.

The obelisk bears an inscription that refers to the king's seizure of goods, people and herds, which he carried back to the city of Ashur. The reliefs of the Obelisk depict military campaigns, hunting, victory banquets and scenes of tribute bearing.

The White Obelisk is a very large four-sided pillar made from white limestone with engraved decoration in relief on all sides of the obelisk, with an inscription at the top.

The carvings show campaigns and recreational activities (including a hunt) of an Assyrian king that has been identified as either Ashurnasirpal I, Tiglath-Pileser II or Ashurnasirpal II.

According to Julian Reade, the style of dress suggests that this impressive stela was set up under the reign of Ashurnasirpal I, since many courtiers wear a Fez-like hat, which is only known from sculptural work made in the thirteenth century BC. If this is the case, the White Obelisk is one of the earliest representations of Assyrian art in existence.

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III was discovered by Sir Austen Henry Layard in 1846 on the citadel of Kalhu. The obelisk was erected by Shalmaneser III and the reliefs depict scenes of tribute bearing as well as the depiction of two subdued rulers, Jehu the Israelite and Sua the Gilzanean, giving gestures of submission to the king. The reliefs on the obelisk have accompanying epigraphs, but besides these the obelisk also possesses a longer inscription that records one of the latest versions of Shalmaneser III's annals, covering the period from his accessional year to his 33rd regnal year.

The Rassam Obelisk, named after its discoverer Hormuzd Rassam, was found on the citadel of Nimrud (ancient Kalhu). It was erected by Ashurnasirpal II, though only survives in fragments. The surviving parts of the reliefs depict scenes of tribute bearing to the king from Syria and the west.

The Black and Rassam Obelisks were both set up in what seems to have been the central square in the citadel of Nimrud, presumably a very public space, and the White in Nineveh. All record much the same types of scenes as the narrative sections of wall-relief, and the gates. The Black Obelisk concentrates on scenes of the bringing of tribute from conquered kingdoms, including Israel, while the White also has scenes of war, hunting, and religious figures. The White Obelisk, from 1049-1031, and the "Broken Obelisk" from 1074-1056, predate the earliest known wall-reliefs by 160 years or more, but are respectively in worn and fragmentary condition.

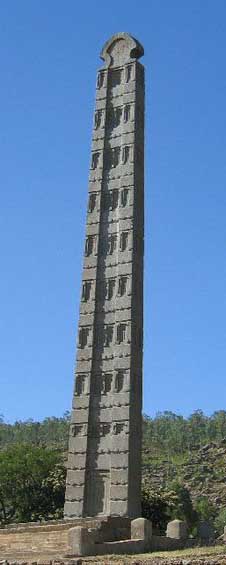

A number of obelisks were carved in the ancient Axumite Kingdom of Ethiopia. Together with (21 m high) King Ezana's Stele, the last erected one and the only unbroken, the most famous example of axumite obelisk is the so-called (24 m high) Obelisk of Axum. It was carved around the 4th century AD and, in the course of time, it collapsed and broke into three parts. In these conditions it was found by Italian soldiers in 1935, after the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, looted and taken to Rome in 1937, where it stood in the Piazza di Porta Capena. Italy agreed in a 1947 UN agreement to return the obelisk but did not affirm its agreement until 1997, after years of pressure and various controversial settlements. In 2003 the Italian government made the first steps toward its return, and in 2008 it was finally re-erected.

The largest obelisk, Great Stele at Axum, now fallen, at 33 m high and 3 by 2 meters at the base (520 tons) is one of the largest single pieces of stone ever worked in human history (the largest is either at Baalbek or the Ramesseum) and probably fell during erection or soon after, destroying a large part of the massive burial chamber underneath it. The obelisks, properly termed stelae or the native hawilt or hawilti as they do not end in a pyramid, were used to mark graves and underground burial chambers. The largest of the grave markers were for royal burial chambers and were decorated with multi-story false windows and false doors, while nobility would have smaller less decorated ones. While there are only a few large ones standing, there are hundreds of smaller ones in "stelae fields".

Walled Obelisk, Hippodrome of Constantinople. Built by Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (905-959) and originally covered with gilded bronze plaques.

The obelisk stone (rock) crosses of Kerala form another category of obelisks. The Syrian Christians or St. Thomas Christians of Malabar on the west coast of India had close contacts with the Egyptian and Assyrian worlds, the original habitat of obelisks. The "Ray of the Sun" and Horus concepts are to be found in the idea of Christ and in the orientation of the churches East-West. The use of the cylinder and socket method is found in both structures.

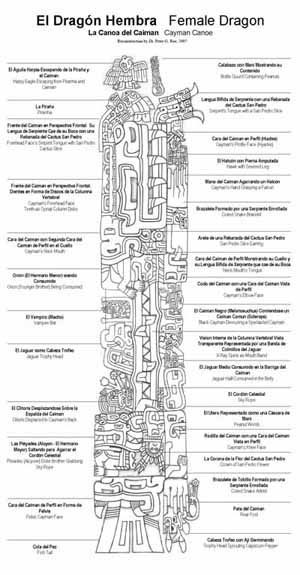

Tello Obelisk

The "Tello Obelisk", from Chavin de Huantar, which used to be housed in the Museo Nacional de Arqueologia, Antropologia e Historia del Peru in Lima until it was relocated to the Museo Nacional de Chavin in July 2008, is a monolith stele with obelisk-like proportions.

I live across the street from historic John Paul Jones Park in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn that features this obelisk. The monument has a pyramid-shaped copper capstone - or pyramidion.

In 2004 my friend threw a quartz crystal onto the ledge before I taught workshop about crystals

Local pigeons must have come to see what was going on.

Selfie at Midnight