Late 69 BC - August 12, 30 BC

Late 69 BC - August 12, 30 BC

Cleopatra VII Philopator was the last person to rule Egypt as an Egyptian pharaoh. After her death Egypt became a Roman province.

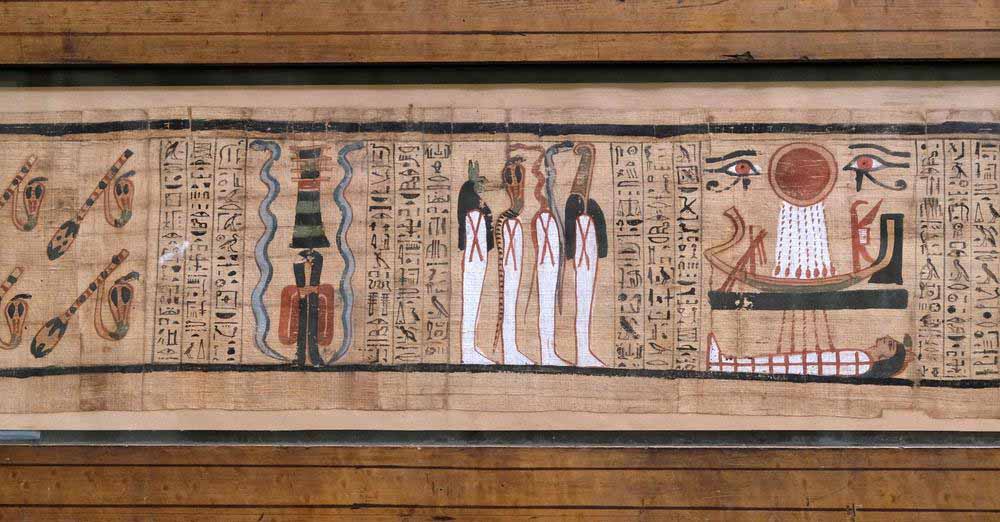

Cleopatra VII was a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty of Ancient Egypt, and therefore was a descendant of one of Alexander the Great's generals who had seized control over Egypt after Alexander's death. Most Ptolemeis spoke Greek and refused to learn Egyptian, which is the reason that Greek as well as Egyptian languages were used on official court documents like the Rosetta Stone By contrast, Cleopatra learned Egyptian and represented herself as the reincarnation of an Egyptian Goddess.

Cleopatra originally ruled jointly with her father Ptolemy XII Auletes and later with her brothers, Ptolemy XIII and Ptolemy XIV, whom she married as per Egyptian custom, but eventually she became sole ruler. As pharaoh, she consummated a liaison with Gaius Julius Caesar that solidified her grip on the throne. She later elevated her son with Caesar, Caesarion, to co-ruler in name.

After Caesar's assassination in 44 BC, she aligned with Mark Antony in opposition to Caesar's legal heir, Gaius Julius Caesar Octavian (later known as Augustus). With Antony, she bore the twins Cleopatra Selene II and Alexander Helios, and another son, Ptolemy Philadelphus.

Her unions with her brothers produced no children. After losing the Battle of Actium to Octavian's forces, Antony committed suicide. Cleopatra followed suit, according to tradition killing herself by means of an asp bite on August 12, 30 BC. She was briefly outlived by Caesarion, who was declared pharaoh, but he was soon killed on Octavian's orders. Egypt became the Roman province of Aegyptus.

Though Cleopatra bore the ancient Egyptian title of pharaoh, the Ptolemaic dynasty was Hellenistic, having been founded 300 years before by Ptolemy I Soter, a Macedonian Greek general of Alexander the Great. As such, Cleopatra's language was the Greek spoken by the Hellenic aristocracy, though she was reputed to be the first ruler of the dynasty to learn Egyptian.

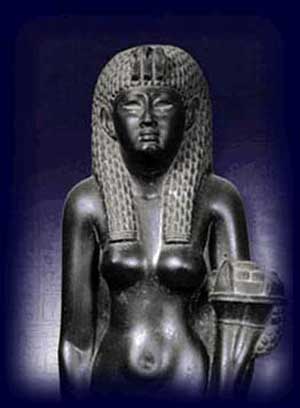

She also adopted common Egyptian beliefs and deities. Her patron goddess was Isis, and thus, during her reign, it was believed that she was the re-incarnation and embodiment of the goddess of wisdom. Her death marked the end of the Ptolemaic Kingdom and Hellenistic period and the beginning of the Roman era in the eastern Mediterranean.

To this day, Cleopatra remains a popular figure in Western culture. Her legacy survives in numerous works of art and the many dramatizations of her story in literature and other media, including William Shakespeare's tragedy Antony and Cleopatra, Jules Massenet's opera Cleopatre and the 1963 film Cleopatra.

In most depictions, Cleopatra is put forward as a great beauty and her successive conquests of the world's most powerful men are taken to be proof of her aesthetic and sexual appeal. In his Pensees, philosopher Blaise Pascal contends that Cleopatra's classically beautiful profile changed world history: "Cleopatra's nose, had it been shorter, the whole face of the world would have been changed."

The identity of Cleopatra's mother is unknown, but she is generally believed to be Cleopatra V Tryphaena of Egypt, the sister or cousin and wife of Ptolemy XII, or possibly another Ptolemaic family member who was the daughter of Ptolemy X and Cleopatra Berenice III Philopator if Cleopatra V was not the daughter of Ptolemy X and Berenice III. Cleopatra's father Auletes was a direct descendant of Alexander the Great's general, Ptolemy I Soter, son of Arsinoe and Lacus, both of Macedon.

Centralization of power and corruption led to uprisings in and the losses of Cyprus and Cyrenaica, making Ptolemy's reign one of the most calamitous of the dynasty. When Ptolemy went to Rome with Cleopatra, Cleopatra VI Tryphaena seized the crown but died shortly afterwards in suspicious circumstances. It is believed, though not proven by historical sources, that Berenice IV poisoned her so she could assume sole rulership. Regardless of the cause, she did until Ptolemy Auletes returned in 55 BC, with Roman support, capturing Alexandria aided by Roman general Aulus Gabinius. Berenice was imprisoned and executed shortly afterwards, her head allegedly being sent to the royal court on the decree of her father, the king. Cleopatra was now, at age 14, put as joint regent and deputy of her father, although her power was likely to have been severely limited.

Ptolemy XII died in March 51 BC, thus by his will making the 18-year-old Cleopatra and her brother, the 12-year-old Ptolemy XIII joint monarchs. The first three years of their reign were difficult, due to economic difficulties, famine, deficient floods of the Nile, and political conflicts. Although Cleopatra was married to her young brother, she quickly made it clear that she had no intention of sharing power with him.

In August 51 BC, relations between Cleopatra and Ptolemy completely broke down. Cleopatra dropped Ptolemy's name from official documents and her face appeared alone on coins, which went against Ptolemaic tradition of female rulers being subordinate to male co-rulers. In 50 BC Cleopatra came into a serious conflict with the Gabiniani, powerful Roman troops of Aulus Gabinius who had left them in Egypt to protect Ptolemy XII after his restoration to the throne in 55 BC. This conflict was one of the main causes for Cleopatra's soon following loss of power.

The sole reign of Cleopatra was finally ended by a cabal of courtiers, led by the eunuch Pothinus, removing Cleopatra from power and making Ptolemy sole ruler in circa 48 BC (or possibly earlier, as a decree exists from 51 BC with Ptolemy's name alone). She tried to raise a rebellion around Pelusium, but she was soon forced to flee with her only remaining sister, Arsinoe.

While Cleopatra was in exile, Pompey became embroiled in the Roman civil war. In the autumn of 48 BC, Pompey fled from the forces of Caesar to Alexandria, seeking sanctuary. Ptolemy, only fifteen years old at that time, had set up a throne for himself on the harbor, from where he watched as on September 28, 48 BC, Pompey was murdered by one of his former officers, now in Ptolemaic service. He was beheaded in front of his wife and children, who were on the ship from which he had just disembarked.

Ptolemy is thought to have ordered the death to ingratiate himself with Caesar, thus becoming an ally of Rome, to which Egypt was in debt at the time, though this act proved a miscalculation on Ptolemy's part. When Caesar arrived in Egypt two days later, Ptolemy presented him with Pompey's severed head; Caesar was enraged. Although he was Caesar's political enemy, Pompey was a Consul of Rome and the widower of Caesar's only legitimate daughter, Julia (who died in childbirth with their son). Caesar seized the Egyptian capital and imposed himself as arbiter between the rival claims of Ptolemy and Cleopatra.

Eager to take advantage of Julius Caesar's anger toward Ptolemy, Cleopatra had herself smuggled secretly into the palace to meet with Caesar. One legend claims she entered past Ptolemy's guards rolled up in a carpet. She became Caesar's mistress, and nine months after their first meeting, in 47 BC, Cleopatra gave birth to their son, Ptolemy Caesar, nicknamed Caesarion, which means "little Caesar".

At this point Caesar abandoned his plans to annex Egypt, instead backing Cleopatra's claim to the throne. After a war lasting six months between the party of Ptolemy XIII and the Roman army of Caesar, Ptolemy XIII was drowned in the Nile and Caesar restored Cleopatra to her throne, with another younger brother Ptolemy XIV as her new co-ruler.

Although Cleopatra was 21 years old when they met and Caesar was 52, they became lovers during Caesar's stay in Egypt between 48 BC and 47 BC. Cleopatra claimed Caesar was the father of her son and wished him to name the boy his heir, but Caesar refused, choosing his grandnephew Octavian instead. During this relationship, it is also rumored that Cleopatra introduced Caesar to her astronomer Sosigenes of Alexandria, who first proposed the idea of leap day and leap years.

Cleopatra, Ptolemy XIV and Caesarion visited Rome in summer 46 BC, where the Egyptian Queen resided in one of Caesar's country houses. The relationship between Cleopatra and Caesar was obvious to the Roman people and it was a scandal, because the Roman dictator was already married to Calpurnia Pisonis. But Caesar even erected a golden statue of Cleopatra represented as Isis in the temple of Venus Genetrix (the mythical ancestress of Caesar's family), which was situated at the Forum Julium.

The Roman orator Cicero said in his preserved letters that he hated the foreign Queen. Cleopatra and her entourage were in Rome when Caesar was assassinated on 15 March, 44 BC. She returned with her relatives to Egypt. When Ptolemy XIV died - allegedly poisoned by his older sister - Cleopatra made Caesarion her co-regent and successor and gave him the epithets Theos Philopator Philometor (= Father- and motherloving God).

In the following Roman civil war between the Caesarian party - led by Mark Antony and Octavian - and the party of the assassins of Caesar - led by Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus - Cleopatra sided with the Caesarian party because of her past. Brutus and Cassius left Italy and sailed to the East of the Roman Empire, where they conquered large areas and established their military basis. At the beginning of 43 BC Cleopatra formed an alliance with the leader of the Caesarian party in the East, Publius Cornelius Dolabella, who recognized Caesarion as her co-ruler.But soon Dolabella was encircled in Laodicea and committed suicide (July 43 BC).

Now Cassius wanted to invade Egypt to seize the treasures of that country and to punish the Queen for her refusal of Cassius' request to send him supplies and her support for Dolabella. Egypt seemed an easy booty because the land did not have strong land forces and there was famine and an epidemic. Cassius finally wanted to prevent that Cleopatra would bring a strong fleet as reinforcement for Antony and Octavian. But he could not execute the invasion of Egypt because at the end of 43 BC Brutus summoned him back to Smyrna.

Cassius tried to blockade Cleopatra's way to the Caesarians. For this purpose Lucius Statius Murcus moved with 60 ships and a legion of elite troops into position at Cape Matapan in the south of the Peloponnese. Nevertheless Cleopatra sailed with her fleet from Alexandria to the west along the Libyan coast to join the Caesarian leaders but her ships were damaged by a violent storm and she became ill, forcing her to return to Egypt. Murcus learned of the misfortune of the Queen and saw parts of her wrecked ships at the coast of Greece. He then sailed with his ships into the Adriatic Sea.

Scientists Recreate Cleopatra's Favorite Perfume Smithsonian - May 24, 2022

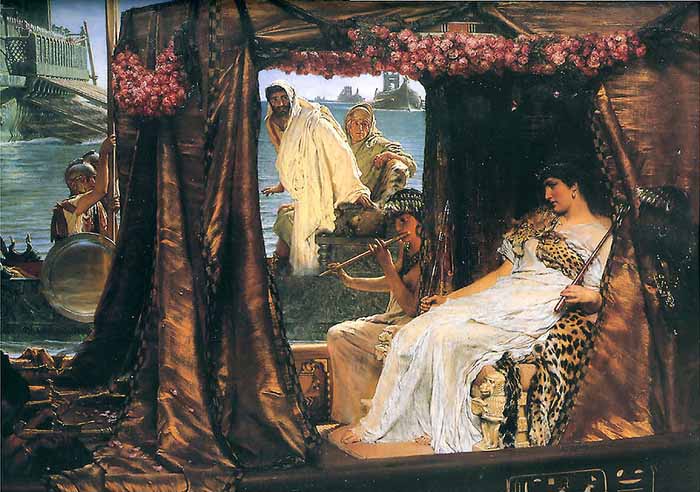

In 41 BC, Mark Antony, one of the triumvirs who ruled Rome in the power vacuum following Caesar's death, summoned Cleopatra to meet him in Tarsus to answer questions about her loyalty. Cleopatra arrived in great state, and so charmed Antony that he chose to spend the winter of 41 BC-40 BC with her in Alexandria.

To safeguard herself and Caesarion, she had Antony order the death of her sister Arsinoe, who was living at the temple of Artemis in Ephesus, which was under Roman control. The execution was carried out in 41 BC on the steps of the temple, and this violation of temple sanctuary scandalized Rome. Cleopatra had also executed her strategos of Cyprus, Serapion, who had supported Cassius against her intentions.

On December 25, 40 BC, Cleopatra gave birth to twins fathered by Antony, Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene II. Four years later, Antony visited Alexandria again en route to make war with the Parthians. He renewed his relationship with Cleopatra, and from this point on Alexandria would be his home. He married Cleopatra according to the Egyptian rite (a letter quoted in Suetonius suggests this), although he was at the time married to Octavia Minor, sister of his fellow triumvir Octavian. He and Cleopatra had another child, Ptolemy Philadelphus.

At the Donations of Alexandria in late 34 BC, following Antony's conquest of Armenia, Cleopatra and Caesarion were crowned co-rulers of Egypt and Cyprus; Alexander Helios was crowned ruler of Armenia, Media, and Parthia; Cleopatra Selene II was crowned ruler of Cyrenaica and Libya; and Ptolemy Philadelphus was crowned ruler of Phoenicia, Syria, and Cilicia. Cleopatra was also given the title of "Queen of Kings" by Antonius.

Her enemies in Rome feared that Cleopatra "was planning a war of revenge that was to array all the East against Rome, establish herself as empress of the world at Rome, cast justice from Capitolium, and inaugurate a new universal kingdom." Caesarion was not only elevated having coregency with Cleopatra, but also proclaimed with many titles, including god, son of god and king of kings, and was depicted as Horus.

a reincarnation of goddess Isis,

as she called herself (Nea Isis).

Relations between Antony and Octavian, disintegrating for several years, finally broke down in 33 BC, and Octavian convinced the Senate to levy war against Egypt. In 31 BC Antony's forces faced the Romans in a naval action off the coast of Actium. Cleopatra was present with a fleet of her own. Popular legend states that when she saw that Antony's poorly equipped and manned ships were losing to the Romans' superior vessels, she took flight and that Antony abandoned the battle to follow her, but no contemporary evidence states this was the case. Following the Battle of Actium, Octavian invaded Egypt. As he approached Alexandria, Antony's armies deserted to Octavian on August 1, 30 BC.

There are a number of unverifiable stories about Cleopatra, of which one of the best known is that, at one of the lavish dinners she shared with Antony, she playfully bet him that she could spend ten million sesterces on a dinner. He accepted the bet. The next night, she had a conventional, unspectacular meal served; he was ridiculing this, when she ordered the second course - only a cup of strong vinegar. She then removed one of her priceless pearl earrings, dropped it into the vinegar, allowed it to dissolve, and drank the mixture. The earliest report of this story comes from Pliny the Elder and dates to about 100 years after the banquet described would have happened. The calcium carbonate in pearls does dissolve in vinegar, but slowly unless the pearl is first crushed.

The ancient sources, particularly the Roman ones, are in general agreement that Cleopatra killed herself by inducing an Egyptian cobra to bite her. The oldest source is Strabo, who was alive at the time of the event, and might even have been in Alexandria. He says that there are two stories: that she applied a toxic ointment, or that she was bitten by an asp.[26] Several Roman poets, writing within ten years of the event, all mention bites by two asps, as does Florus, a historian, some 150 years later.[30] Velleius, sixty years after the event, also refers to an asp. Other authors have questioned these historical accounts, stating that it is possible that Augustus had her killed.

Plutarch, writing about 130 years after the event, reports that Octavian succeeded in capturing Cleopatra in her Mausoleum after the death of Antony. He ordered his freedman Epaphroditus to guard her to prevent her from committing suicide because he allegedly wanted to present her in his triumph. But Cleopatra was able to deceive Epaphroditus and kill herself nevertheless.

Plutarch states that she was found dead, her handmaiden, Iras dying at her feet, and another handmaiden, Charmion, adjusting her crown before she herself falls. He then goes on to state that an asp was concealed in a basket of figs that was brought to her by a rustic, and, finding it after eating a few figs, she held out her arm for it to bite. Other stories state that it was hidden in a vase, and that she poked it with a spindle until it got angry enough to bite her on the arm. Finally, he eventually writes, in Octavian's triumphal march back in Rome, an effigy of Cleopatra that has an asp clinging to it is part of the parade.

Suetonius, writing about the same time as Plutarch, also says Cleopatra died from an asp bite.

Shakespeare gave us the final part of the image that has come down to us, Cleopatra clutching the snake to her breast. Before him, it was generally agreed that she was bitten on the arm.

Plutarch tells us of the death of Antony. When his armies desert him and join with Octavian, he cries out that Cleopatra has betrayed him. She, fearing his wrath, locks herself in her monument with only her two handmaidens and sends messengers to Antony that she is dead. Believing them, Antony stabs himself in the stomach with his sword, and lies on his couch to die. Instead, the blood flow stops, and he begs any and all to finish him off.

Another messenger comes from Cleopatra with instructions to bear him to her, and he, rejoicing that Cleopatra is still alive, consents. She won't open the door, but tosses ropes out of a window. After Antony is securely trussed up, she and her handmaidens haul him up into the monument. This nearly finishes him off. After dragging him in through the window, they lay him on a couch. Cleopatra tears off her clothes and covers him with them. She raves and cries, beats her breasts and engages in self-mutilation. Antony tells her to calm down, asks for a glass of wine, and dies upon finishing it.

The site of their Mausoleum is uncertain, though it is thought by the Egyptian Antiquities Service, to be in or near the temple of Taposiris Magna south west of Alexandria.

Cleopatra's son by Caesar, Caesarion, was proclaimed pharaoh by the Egyptians, after Alexandria fell to Octavian. Caesarion was captured and killed, his fate reportedly sealed when one of Octavian's advisers paraphrased Homer: "It is bad to have too many Caesars." This ended not just the Hellenistic line of Egyptian pharaohs, but the line of all Egyptian pharaohs. The three children of Cleopatra and Antony were spared and taken back to Rome where they were taken care of by Antony's wife, Octavia Minor. The daughter, Cleopatra Selene, was married by arrangements by Octavian to Juba II of Mauretania.

Cleopatra died of drug cocktail not snake bite Telegraph.co.uk - June 29, 2010

Cleopatra's Needle is the popular name for each of three Ancient Egyptian obelisks re-erected in London, Paris, and New York City during the nineteenth century. The London and New York ones are a pair, while the Paris one comes from a different original site where its twin remains. Although the needles are genuine Ancient Egyptian obelisks, they are somewhat misnamed as they have no particular connection with Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt, and were already over a thousand years old in her lifetime. The Paris "needle" was the first to be moved and re-erected, and the first to acquire the nickname.

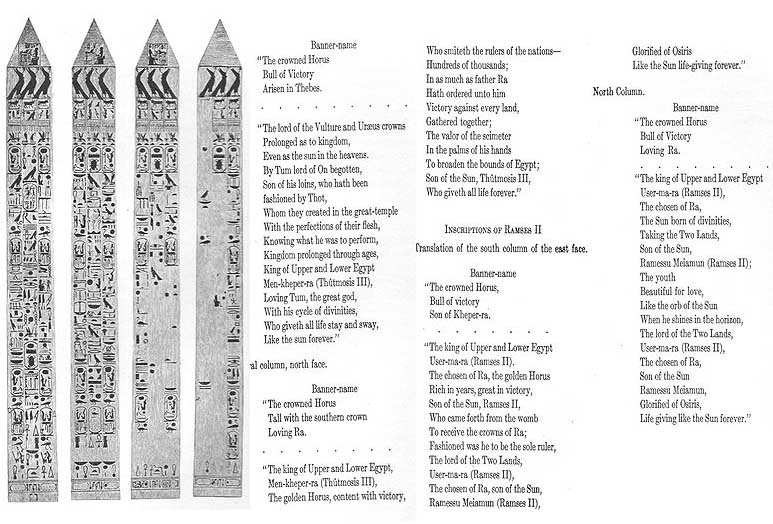

The pair are made of red granite, stand about 21 metres (68 ft) high, weigh about 224 tons and are inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyphs. They were originally erected in the Egyptian city of Heliopolis on the orders of Thutmose III, around 1450 BC. The material of which they were cut is granite, brought from the quarries of Aswan, near the first cataract of the Nile. The inscriptions were added about 200 years later by Ramesses II to commemorate his military victories. The obelisks were moved to Alexandria and set up in the Caesareum - a temple built by Cleopatra in honor of Mark Antony - by the Romans in 12 BC, during the reign of Augustus, but were toppled some time later. This had the fortuitous effect of burying their faces and so preserving most of the hieroglyphs from the effects of weathering.

The London needle is in the City of Westminster, on the Victoria Embankment near the Golden Jubilee Bridges. It is close to the Embankment underground station. It was presented to the United Kingdom in 1819 by the ruler of Egypt and Sudan Muhammad Ali, in commemoration of the victories of Lord Nelson at the Battle of the Nile and Sir Ralph Abercromby at the Battle of Alexandria in 1801. Although the British government welcomed the gesture, it declined to fund the expense of transporting it to London.

The obelisk remained in Alexandria until 1877 when Sir William James Erasmus Wilson, a distinguished anatomist and dermatologist, sponsored its transportation to London at a cost of some 10,000 pds. (a very considerable sum in those days). It was dug out of the sand in which it had been buried for nearly 2,000 years and was encased in a great iron cylinder, 92 feet (28 m) long and 16 feet (4.9 m) in diameter, designed by the engineer John Dixon and dubbed Cleopatra, to be commanded by Captain Carter. It had a vertical stem and stern, a rudder, two bilge keels, a mast for balancing sails, and a deck house. This acted as a floating pontoon which was to be towed to London by the ship Olga, commanded by Captain Booth.

The effort met with disaster on 14 October 1877, in a storm in the Bay of Biscay, when the Cleopatra began wildly rolling, and became untenable. The Olga sent out a rescue boat with six volunteers, but the boat capsized and all six crew were lost - named today on a bronze plaque attached to the foot of the needle's mounting stone. Captain Booth on the Olga eventually managed to get his ship next to the Cleopatra, to rescue Captain Carter and the five crew members aboard Cleopatra. Captain Booth reported the Cleopatra "abandoned and sinking," but instead she drifted in the Bay until found four days later by Spanish trawler boats, then rescued by the Glasgow steamer Fitzmaurice and taken to Ferrol in Spain for repairs.

The Master of the Fitzmaurice lodged a salvage claim of pds. 5,000 which had to be settled before departure from Ferrol, which was negotiated down and settled for pds. 2,000. The William Watkins Ltd paddle tug Anglia under the command of Captain David Glue was then commissioned to tow the Cleopatra back to the Thames. On their arrival in the estuary, the school children of Gravesend were given the day off when she arrived on January 21, 1878. The obelisk was erected on the Victoria Embankment on September 12, 1878.

On erection of the obelisk in 1878 a time capsule was concealed in the front part of the pedestal, it contained : A set of 12 photographs of the best looking English women of the day, a box of hairpins, a box of cigars, several tobacco pipes, a set of imperial weights, a baby's bottle, some children's toys, a shilling razor, a hydraulic jack and some samples of the cable used in erection, a 3' bronze model of the monument, a complete set of British coins, a rupee, a portrait of Queen Victoria, a written history of the strange tale of the transport of the monument, plans on vellum, a translation of the inscriptions, copies of the bible in several languages, a copy of Whitaker's Almanack, a Bradshaw Railway Guide, a map of London and copies of 10 daily newspapers.

Cleopatra's Needle is flanked by two faux-Egyptian sphinxes cast from bronze that bear hieroglyphic inscriptions that say netjer nefer men-kheper-re di ankh (the good god, Thuthmosis III given life). These Sphinxes appear to be looking at the Needle rather than guarding it. This is due to the Sphinxes' improper or backwards installation. The Embankment has other Egyptian flourishes, such as buxom winged sphinxes on the armrests of benches.

On September 4, 1917, during World War I, a bomb from a German air raid landed near the needle. In commemoration of this event, the damage remains unrepaired to this day and is clearly visible in the form of shrapnel holes and gouges on the right-hand sphinx. Restoration work was carried out in 2005. The original Master Stone Mason who worked on the granite foundation was Lambeth-born William Henry Gould (1822-1891).

The New York needle, Pompey's Pillar, was erected in Central Park on February 22, 1881. It was secured in May 1877 by judge Elbert E. Farman, the then-United States Consul General at Cairo, as a gift from Khedive for the United States remaining a friendly neutral as the European powers-France and Britain maneuvered to secure political control of the Egyptian Government.

The original idea to secure an Egyptian obelisk for New York City came out of the March 1877 New York City newspaper accounts of the transportation of the London obelisk. If Paris had one and London was to get one, why should not New York get one? The newspapers mistakenly attributed to a Mr. John Dixon the 1869 proposal of the Khedive of Egypt to give the United States the remaining Alexandria obelisk as a gift for increased trade.

Mr. Dixon was the 1877 contractor who arranged the transport of the London obelisk and denied the newspaper accounts. In March 1877 and based on the newspaper accounts, Mr. Henry G. Stebbins, then Commissioner of the Department of Public Parks of the City of New York, undertook to secure the funding to transport the obelisk to New York. When the railroad magnate William H. Vanderbilt was asked to head the subscription, he generously offered to finance the project with a donation of over $100,000.

Mr. Stebbins then sent two acceptance letters to the Khedive through the Department of State which forwarded them to Judge Farman in Cairo. Realizing that the New York accounts were false and that he might be able to secure one of the two remaining upright obelisks either the mate to the Paris obelisk in Luxor or the London mate in Alexandria; Judge Farman formally asked the Khedive in March 1877 and by May 1877 he had secured the gift in writing.

The surface of the stone is heavily weathered, nearly masking the rows of hieroglyphics engraved on all sides. Photographs taken near the time the obelisk was erected in the park show that the inscriptions or hieroglyphics, as depicted below with translation, were still quite legible and date first from Thutmosis III (1479-1425 BCE) and then nearly 300 years later, Ramesses II the Great (1279-1213 BCE). The stone had stood in the clear dry Egyptian desert air for nearly 3000 years and had undergone little weathering. In a little more than a century in the climate of New York City, pollution and acid rain have heavily pitted its surfaces.

The Paris Needle (L'aiguille de Cleopatre) is in the Place de la Concorde. The centre of the Place is occupied by the giant Egyptian obelisk decorated with hieroglyphics exalting the reign of the pharaoh Ramesses II. It once marked the entrance to the Luxor Temple. The ruler of Egypt and Sudan, Muhammad Ali, presented the 3,300-year-old Luxor Obelisk to France in 1826.

King Louis-Philippe had it placed in the centre of Place de la Concorde in 1833 near the spot where Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette had been guillotined in 1793. Given the technical limitations of the day, transporting it was difficult - on the pedestal are diagrams explaining the machinery used for its transportation.

The red granite column rises 23 metres high, including the base, and weighs over 250 tonnes. Missing its original cap, believed stolen in the 6th century BC, in 1998 the government of France added a goldleafed pyramid cap to the top of the obelisk. The obelisk is flanked by two fountains constructed at the time of its erection on the Place.

Since the Paris obelisk was already described as "l'Aiguille de Cleopatre" by 1877, before either the London or New York needles were erected, it appears to be the origin of the nickname. However, it is now more often referred to more formally as "the Luxor Obelisk".