22q11.2 deletion syndrome, which has several presentations including DiGeorge syndrome (DGS), DiGeorge anomaly, velo-cardio-facial syndrome, Shprintzen syndrome, conotruncal anomaly face syndrome, Strong syndrome, congenital thymic aplasia, and thymic hypoplasia, is a syndrome caused by the deletion of a small piece of chromosome 22. The deletion occurs near the middle of the chromosome at a location designated 22q11.2-signifying its location on the long arm of one of the pair of chromosomes 22, on region 1, band 1, sub-band 2. It has a prevalence estimated at 1:4000. The syndrome was described in 1968 by the pediatric endocrinologist Angelo DiGeorge. deletion is also associated with truncus arteriosus.

The features of this syndrome vary widely, even among members of the same family, and affect many parts of the body. Characteristic signs and symptoms may include birth defects such as congenital heart disease, defects in the palate, most commonly related to neuromuscular problems with closure (velo-pharyngeal insufficiency), learning disabilities, mild differences in facial features, and recurrent infections. Infections are common in children due to problems with the immune system's T-cell mediated response that in some patients is due to an absent or hypoplastic thymus. 22q11.2 deletion syndrome may be first spotted when an affected newborn has heart defects or convulsions from hypocalcemia due to malfunctioning parathyroid glands and low levels of parathyroid hormone (parathormone).

Affected individuals may also have any other kind of birth defect including kidney abnormalities and significant feeding difficulties as babies. Disorders such as hypothyroidism and hypoparathyroidism or thrombocytopenia (low platelet levels), and psychiatric illnesses are common late-occurring features. Microdeletions in chromosomal region 22q11.2 are associated with a 20 to 30-fold increased risk of schizophrenia.

Studies provide various rates of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome in schizophrenia, ranging from 0.5 to 2% and averaging about 1%, compared with the overall estimated 0.025% risk of the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome in the general population.

Study finds biomarkers for psychiatric symptoms in patients with rare genetic condition 22q Medical Express - April 26, 2024

It found unique biomarkers that could identify patients with 22q who may be more likely to develop schizophrenia or psychiatric conditions, including psychosis, which is commonly associated with 22q. People with 22q are missing a piece of chromosome 22 that contains more than 30 genes. This loss can lead to a variety of health challenges, including heart issues, psychosis, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism and other conditions. However, it is not clear which genes in the deleted region lead to these symptoms.

The research team focused on the likelihood of patients with 22q developing psychosis, a condition characterized by difficulty recognizing what is real and what is not. This condition can affect up to 20% of patients with 22q in their late teens to mid-twenties. Without good diagnostic tests, it is almost impossible to predict which patients face these risks. Early detection would help patients start treatments when most helpful.

Brain Researchers Find Early Warning For Cognitive Decline Red Orbit - September 18, 2013

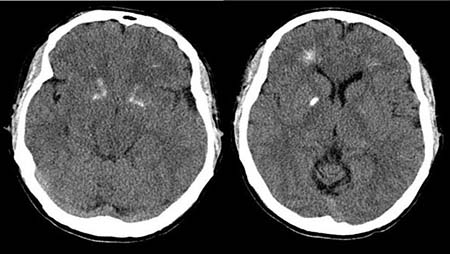

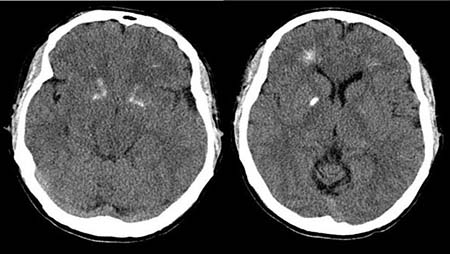

22q11.2 deletion syndrome is associated with Parkinson's disease is very exciting. The varying pathology that we found is reminiscent of certain other genetic causes of Parkinson's disease, and opens new directions to search for novel genes that could cause its more common form. Studies of patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome before they ever develop clinical features of Parkinson's disease may not only provide important information on the effectiveness of screening methods for early detection of the disease, but also allow for future ‘neuroprotective treatments' to be introduced at the ultimate time when they can have a chance to make an important impact on preventing the disease or slowing its course. Most people with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome will not develop Parkinson's disease said co-author Dr. Anne Bassett, a geneticist at the University of Toronto. But it does occur at a rate higher than in the general population.

Study finds that a subset of children often considered to have autism may be misdiagnosed PhysOrg - September 18, 2013

Children with a genetic disorder called 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, who frequently are believed to also have autism, often may be misidentified because the social impairments associated with their developmental delay may mimic the features of autism, a study by researchers with the UC Davis MIND Institute suggests.

The study is the first to examine autism in children with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, in whom the prevalence of autism has been reported at between 20 and 50 percent, using rigorous gold-standard diagnostic criteria. The research found that none of the children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome "met strict diagnostic criteria" for autism. The researchers said the finding is important because treatments designed for children with autism, such as widely used discrete-trial training methods, may exacerbate the anxiety that is commonplace among the population.

Rather, evaluations should be performed to assess autism and guide the selection of appropriate therapies based on the children's symptoms, such as language and communication delay, the researchers said. The study, "Social impairments in Chromosome 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome (22q11.2DS): Autism Spectrum Disorder or a different Endophenotype?" is published online today in Springer's Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

A high prevalence of autism spectrum disorder has been reported in children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome - as high as 50 percent based on parent-report measures. Children diagnosed with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome - or 22q - may experience mild to severe cardiac anomalies, weakened immune systems and malformations of the head and neck and the roof of the mouth, or palate. They also experience developmental delay, with IQs in the borderline-to-low-average range. They characteristically experience significant anxiety and appear socially awkward.

"The results of our study show that of the children involved in our study no child actually met strict diagnostic criteria for an autism spectrum disorder," said Kathleen Angkustsiri, study lead author and assistant professor of developmental-behavioral pediatrics at the MIND Institute.

"This is very important because the literature cites rates of anywhere from 20 to 50 percent of children with the disorder also have an autism spectrum disorder. Our findings lead us to question whether this is the correct label for these children who clearly have social impairments. We need to find out what interventions are most appropriate for their difficulties."

The disorder's name also describes its location on the 22nd chromosome as well as the nature of the genetic mutation, which is associated with a variety of anatomical and intellectual deficits. It has previously been known as Velocardiofacial Syndrome and Di George Syndrome, for the pediatric endocrinologist who described it in the 1960s.

The risk of 22q is about 1 in 2000 in the general population. The condition is seen in individuals of all backgrounds. Notably, people with 22q are at significantly heightened risk of developing mental-health disorders in adolescence and young adulthood. A person with 22q has a 30 times greater risk of developing schizophrenia than individuals in the general population.

"Because of the high rates of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adulthood, 22q is a very special population for prospective study looking at what's happening throughout childhood that might either increase risk or provide protection against some of the later developing serious psychiatric illnesses, such as schizophrenia, that are associated with the disorder," said Tony J. Simon, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and director of the chromosome 22q11.2 deletion program at the MIND Institute.

The study was conducted among individuals recruited through the website of the Cognitive Analysis and Brain Imaging Laboratory (CABIL), which Simon directs. Simon and Angkustsiri said that the parents of children with 22q deletion syndrome often had commented that their children "seemed different" from other children with autism diagnoses, but that they hadn't discovered a better diagnosis.

The clinical impression of the MIND Institute's 22q deletion syndrome team, which includes psychologists Ingrid Leckliter and Janice Enriquez, was that the children were experiencing significant social impairments, but their presentation diverged from that of children with autism. To determine whether the children met the criteria for classic autism, they decided to test a subset of the children recruited from participants in a larger study of neurocognitive functioning, based on stringent methods and using multiple testing instruments.

The researchers selected 29 children - 16 boys and 13 girls - for additional scrutiny, administering two tests. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), a gold-standard assessment for autism, was administered to the children. The Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ), a 40-question parent screening tool for communication and social functioning based on the gold-standard Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised, was administered to their parents.

Typically, a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder requires elevated scores on both a parent report measure, such as the SCQ, and a directly administered assessment such as the ADOS. Prior studies of autism in chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome have only used parent report measures.

Only five of the 29 children had scores in the elevated range on the ADOS diagnostic tool. Four of the five had significant anxiety. Only two - 7 percent - had SCQ scores above the cut off. No child had both SCQ and ADOS scores in the relevant ranges that would lead to an ASD diagnosis.

"Over the years, a number of children came to us as part of the research or the clinical assessments that we perform, and their parents told us that they had an autism spectrum diagnosis. It's quite clear that children with the disorder do have social impairments," Simon said. "But it did seem to us that they did not have a classic case of autism spectrum disorder. They often have very high levels of social motivation. They get a lot of pleasure from social interaction, and they're quite socially skilled."

Simon said that the team also noted that the children's social deficits might be more a function of their developmental delay and intellectual disability than autism. "If you put them with their younger siblings' friends they function very well in a social setting," Simon continued, "and they interact well with an adult who accommodates their expectations for social interaction."

Angkustsiri said that further study is needed to assess more appropriate treatments for children with 22q, such as improving their communication skills, treating their anxiety, helping them to remain focused and on task. "There are a variety of different avenues that might be pursued rather than treatments that are designed to treat children with autism," Angkustsiri said. "There are readily available, evidence-based treatments that may be more appropriate to help maximize these children's potential."