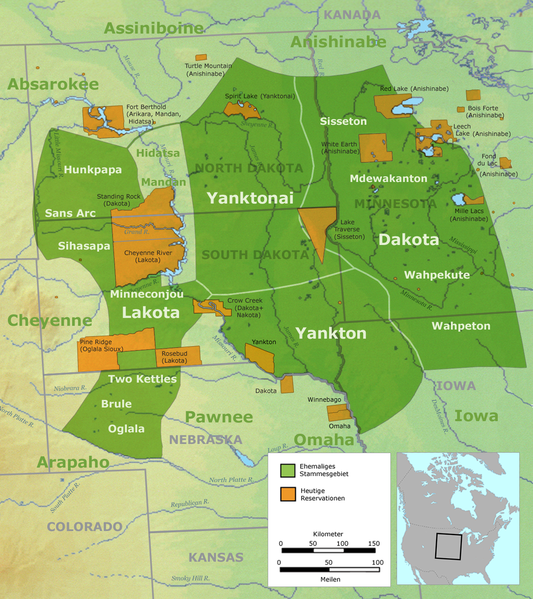

The Sioux are Native American and First Nations people in North America. The term can refer to any ethnic group within the Great Sioux Nation or any of the nation's many language dialects. Their territory covers some 200,000 km2 in the present day state of South Dakota and neighboring states.

The Lakota, Dakota and Nakota Nation (also known as the Great Sioux Nation) descends from of the original inhabitants of North America and can be divided into three major linguistic and geographic groups: Lakota (Teton, West Dakota), Nakota (Yankton, Central Dakota) and Dakota (Santee, Eastern Dakota). The total number of native North Americans is approximately 1.5 million, of which around 100,000 are Lakota. They reside near the Sacred Black Hills of South Dakota.

The Sioux maintain many separate tribal governments scattered across several reservations and communities in North America: in the Dakotas, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Montana in the United States; and in Manitoba, southern Saskatchewan and Alberta in Canada.

The earliest known European record of the Sioux identified them in Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin. After the introduction of the horse in the early 18th century, the Sioux dominated larger areas of land - from present day Central Canada to the Platte River, from Minnesota to the Yellowstone River, including the Powder River country.

The Lakota, also known as Teton, Tetonwan ("dwellers of the prairie"), Teton Sioux ("snake, or enemy") are a Native American tribe. They are part of a confederation of seven related Sioux tribes (the Oceti Sakowin, or seven council fires) and speak Lakota, one of the three major dialects of the Sioux language. The Lakota are the western-most of the three Sioux-language groups, occupying lands in both North and South Dakota.

The Lakota were originally referred to as the Dakota when they lived by the Great Lakes. Encroaching European-American settlement in Canada eventually led them to migrate west from the Great Lakes region. They later called themselves the Lakota, and were also known as Sioux. They were introduced to horses by the Cheyenne about 1730.

After their adoption of the horse, their society centered on the buffalo hunt on horseback. The total population of the Sioux (Lakota, Santee, Yankton, and Yanktonai) was estimated at 28,000 by French explorers in 1660. The Lakota population was first estimated at 8,500 in 1805, growing steadily and reaching 16,110 in 1881. The Lakota were, thus, one of the few Indian tribes to increase in population in the 19th century. The number of Lakota has now increased to about 70,000, of whom about 20,500 still speak the Lakota language.

After 1720, the Lakota branch of the Seven Council Fires split into two major sects, the Saone who moved to the Lake Traverse area on the South DakotaŠNorth DakotaŠMinnesota border, and the Oglala-Sicangu who occupied the James River valley. By about 1750, however, the Sane had moved to the east bank of the Missouri River, followed 10 years later by the Oglala and Brule (Sicangu).

The large and powerful Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa villages had long prevented the Lakota from crossing the Missouri. However, the great smallpox epidemic of 1772-1780 destroyed three-quarters of these tribes. The Lakota crossed the river into the drier, short-grass prairies of the High Plains. These newcomers were the Saone, well-mounted and increasingly confident, who spread out quickly.

In 1765, a Saone exploring and raiding party led by Chief Standing Bear discovered the Black Hills (the Paha Sapa), then the territory of the Cheyenne. Ten years later, the Oglala and Brule also crossed the river. In 1776, the Lakota defeated the Cheyenne, who had earlier taken the region from the Kiowa. The Cheyenne then moved west to the Powder River country, and the Lakota made the Black Hills their home.

Initial United States contact with the Lakota during the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-1806 was marked by a standoff. Lakota bands refused to allow the explorers to continue upstream, and the expedition prepared for battle, which never came.

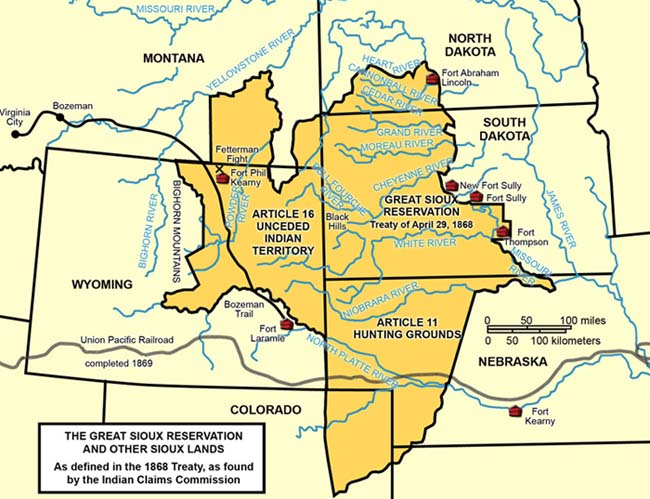

Nearly half a century later, after the United States Army had built Fort Laramie without permission on Lakota land, the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 was negotiated to protect travelers on the Oregon Trail. The Cheyenne and Lakota had previously attacked emigrant parties in a competition for resources, and also because some settlers had encroached on their lands. The Fort Laramie Treaty acknowledged Lakota sovereignty over the Great Plains in exchange for free passage on the Oregon Trail for "as long as the river flows and the eagle flies".

The United States government did not enforce the treaty restriction against unauthorized settlement. Lakota and other bands attacked settlers and even emigrant trains, causing public pressure on the US Army to punish the hostiles. On September 3, 1855, 700 soldiers under American General William S. Harney avenged the Grattan Massacre by attacking a Lakota village in Nebraska, killing about 100 men, women, and children. A series of short "wars" followed, and in 1862Š1864, as refugees from the "Dakota War of 1862" in Minnesota fled west to their allies in Montana and Dakota Territory. Increasing illegal settlement after the American Civil War caused war once again.

The Black Hills were considered sacred by the Lakota, and they objected to mining. In 1868, the United States signed the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, exempting the Black Hills from all white settlement forever. Four years later gold was discovered there, and prospectors descended on the area.

The attacks on settlers and miners were met by military force conducted by army commanders such as Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer. General Philip Sheridan encouraged his troops to hunt and kill the buffalo as a means of "destroying the Indians' commissary."

The allied Lakota and Arapaho bands and the unified Northern Cheyenne were involved in much of the warfare after 1860. They fought a successful delaying action against General George Crook's army at the Battle of the Rosebud, preventing Crook from locating and attacking their camp, and a week later defeated the U.S. 7th Cavalry in 1876 at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, which the Lakota call the Greasy Grass Fight. Custer attacked a camp of several tribes, much larger than he realized. Their combined forces killed 258 soldiers, wiping out the entire Custer battalion, and inflicting more than 50% casualties on the regiment.

Their victory over the U.S. Army would not last, however. The US Congress authorized funds to expand the army by 2500 men. The reinforced US Army defeated the Lakota bands in a series of battles, finally ending the Great Sioux War in 1877. The Lakota were eventually confined onto reservations, prevented from hunting buffalo and forced to accept government food distribution.

In 1877 some of the Lakota bands signed a treaty ceding the Black Hills to the United States. Low-intensity conflicts continued. Fourteen years later, Sitting Bull was killed at Standing Rock reservation on December 15, 1890. The US Army attacked Spotted Elk (aka Bigfoot), Mnicoujou band of Lakota at the Wounded Knee Massacre on December 29, 1890 at Pine Ridge.

Today, the Lakota are found mostly in the five reservations of western South Dakota: Rosebud Indian Reservation (home of the Upper Sicangu or Brule), Pine Ridge Indian Reservation (home of the Oglala), Lower Brule Indian Reservation (home of the Lower Sicangu), Cheyenne River Indian Reservation (home of several other of the seven Lakota bands, including the Mnikoju, Itazipco, Sihasapa and Oohenumpa), and Standing Rock Indian Reservation (home of the Hunkpapa), also home to people from many bands. Lakota also live on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in northeastern Montana, the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation of northwestern North Dakota, and several small reserves in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Their ancestors fled to "Grandmother's [i.e. Queen Victoria's] Land" (Canada) during the Minnesota or Black Hills War.

Large numbers of Lakota live in Rapid City and other towns in the Black Hills, and in metro Denver. Lakota elders joined the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) to seek protection and recognition for their cultural and land rights. It is a little known fact that some of the American Sign Language came from the Lakota Sioux.

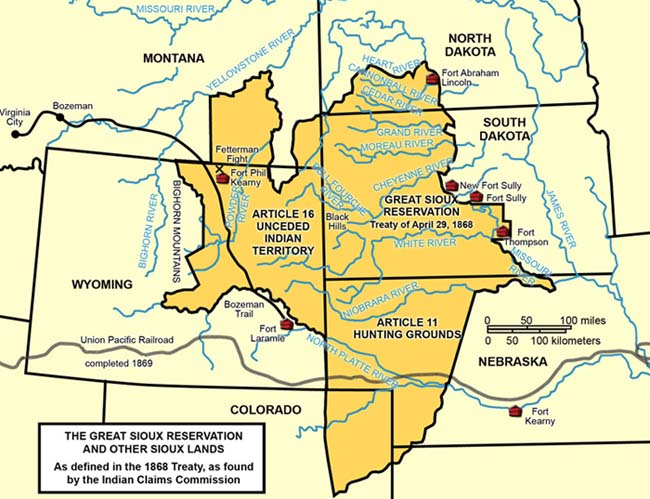

Chief Rain In The Face was a Hunkpapa Lakota, born around 1835 near the forks of the Cheyenne River in present-day North Dakota. According to his own testimony, he first received the name as a result of a boyhood fight in which blood smeared his face paint, much as rain. Another version, popular among whites, told that as an infant he was left in a storm long enough for rain to splatter his face.

During his youth, Rain In The Face rose to prominence as a warrior and was a major leader in the Lakota wars of the 1860s and 1870s. Following the Battle of the Little Bighorn, he accompanied Sitting Bull to Canada and returned with him to the United States in 1881. Like many other former Lakota warriors he became a reservation policeman, performing many of the traditional functions of an akicita or camp patrolman.

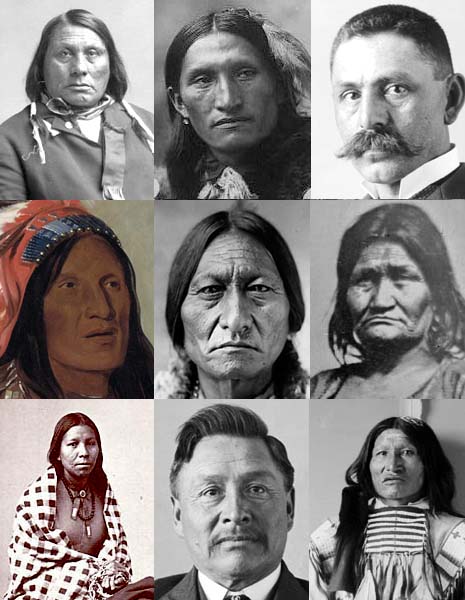

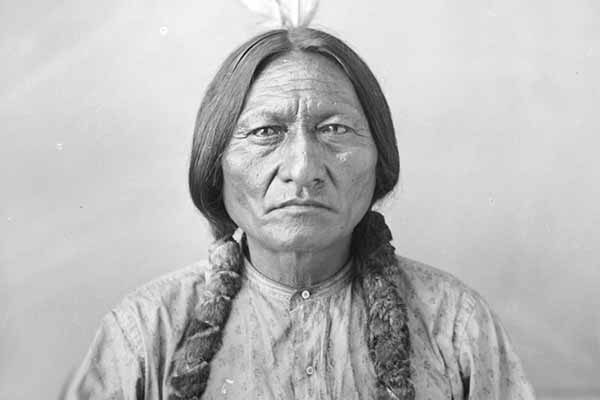

Sitting Bull was a Lakota Medicine Man and Chief was considered the last Sioux to surrender to the U.S. Government. He was a Native American shaman and leader of the Hunkpapa Sioux, who led 3,500 Sioux and Cheyenne warriors against the US 7th Cavalry under George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876.

Though he did not participate personally in the battle, the chiefs were spurred on by a dream that Sitting Bull had in which a group of American soldiers tumbled into his encampment.

Blamed for the ensuing massacre, Sitting Bull led his tribe into Canada, where they lived until 1881, when on July 20 he led the last of his fugitive people in surrender to United States troops at Fort Buford in Montana. The US government, however, had granted him amnesty.

In later life, Sitting Bull toured with Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show, where he was a popular attraction. Often asked to address the audience, he frequently cursed them in his native Lakota language to the wild applause of his listeners.

Toward the end of his life, Sitting Bull was drawn to the mystical Ghost Dance as a way of repelling the white invaders from his people's land. Although he himself was not a follower, this was perceived as a threat by the American government, and a group of Indian police was sent to arrest him. In the ensuing scuffle, Sitting Bull and his son Crow Foot were killed.

Gall (Pizi), known also as Man Who Goes In The Middle and Red Walker, was a close ally and younger brother of Sitting Bull. He is best remembered for mounting the successful counterattack on Commander Marcus Reno's troops during the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Discovering that his wives and children were victims of Reno's assault, Gall threw himself into the remaining conflict with unbridled passion, observing later that their loss had "made his heart bad."

Following the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Gall lived with Sitting Bull's camp in Canada from 1877 to 1881. Returning to the United States, he joined the rest of the Hunkpapas on Standing Rock Reservation where he attempted to help his people adapt to the changes demanded of them by assimilationist polices. His willingness to cooperate with white officials led Sitting Bull and other traditionalists to brand him a traitor. Gall died in Oak Creek, South Dakota in 1894.

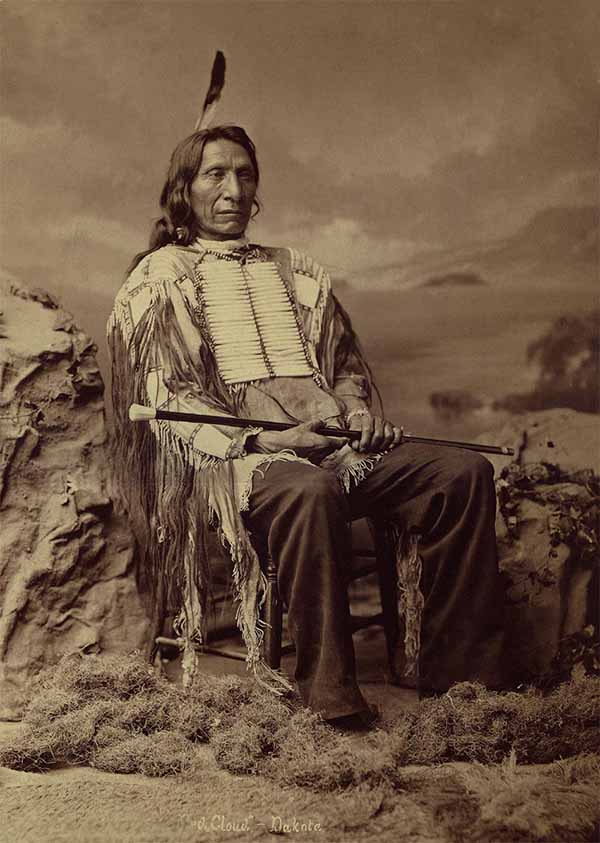

Beginning in 1866, Red Cloud orchestrated the most successful war against the United States ever fought by an Indian nation. The army had begun to construct forts along the Bozeman Trail, which ran through the heart of Lakota territory in present-day Wyoming to the Montana gold fields from Colorado's South Platte River. As caravans of miners and settlers began to cross the Lakota's land, Red Cloud was haunted by the vision of Minnesota's expulsion of the Eastern Lakota in 1862 and 1863.

So he launched a series of assaults on the forts, most notably the crushing defeat of Lieutenant Colonel William Fetterman's column of eighty men just outside Fort Phil Kearny, Wyoming, in December of 1866. The garrisons were kept in a state of exhausting fear of further attacks through the rest of the winter.

Red Cloud's strategies were so successful that by 1868 the United States government had agreed to the Fort Laramie Treaty. The treaty's remarkable provisions mandated that the United States abandon its forts along the Bozeman Trail and guarantee the Lakota their possession of what is now the Western half of South Dakota, including the Black Hills, along with much of Montana and Wyoming.

The peace, of course, did not last. Custer's 1874 Black Hills expedition again brought war to the northern Plains, a war that would mean the end of independent Indian nations. For reasons which are not entirely clear, Red Cloud did not join Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull and other war leaders in the Lakota War of 1876-77. However, after the military defeat of the Lakota nation, Red Cloud continued to fight for the needs and autonomy of his people, even if in less obvious or dramatic ways than waging war.

Throughout the 1880's Red Cloud struggled with Pine Ridge Indian Agent Valentine McGillycuddy over the distribution of government food and supplies and the control of the Indian police force. He was eventually successful in securing McGillycuddy's dismissal. Red Cloud cultivated contacts with sympathetic Eastern reformers, especially Thomas A. Bland, and was not above pretending for political effect to be more acculturated to white ways than he actually was.

Fearing the Army's presence on his reservation, Red Cloud refrained from endorsing the Ghost Dance movement, and unlike Sitting Bull and Big Foot, he escaped the Army's occupation unscathed. Thereafter he continued to fight to preserve the authority of chiefs such as himself, opposed leasing Lakota lands to whites, and vainly fought allotment of Indian reservations into individual tracts under the 1887 Dawes Act. He died in 1909, but his long and complex life endures as testimony to the variety of ways in which Indians resisted their conquest.

Red Cloud's War (also referred to as the Bozeman War) was an armed conflict between the Lakota and the United States in the Wyoming Territory and the Montana Territory from 1866 to 1868. The war was fought over control of the Powder River Country in north central Wyoming.

The war is named after Red Cloud, a prominent Sioux chief who led the war against the United States following encroachment into the area by the U.S. military. The war ended with the Treaty of Fort Laramie. The Sioux victory in the war led to their temporarily preserving their control of the Powder River country.

Celebrated for his ferocity in battle, Crazy Horse was recognized among his own people as a visionary leader committed to preserving the traditions and values of the Lakota way of life.

Even as a young man, Crazy Horse was a legendary warrior. He stole horses from the Crow Indians before he was thirteen, and led his first war party before turning twenty. Crazy Horse fought in the 1865-68 war led by the Oglala chief Red Cloud against American settlers in Wyoming, and played a key role in destroying William J. Fetterman's brigade at Fort Phil Kearny in 1867.

Crazy Horse earned his reputation among the Lakota not only by his skill and daring in battle but also by his fierce determination to preserve his people's traditional way of life. He refused, for example, to allow any photographs to be taken of him. And he fought to prevent American encroachment on Lakota lands following the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, helping to attack a surveying party sent into the Black Hills by General George Armstrong Custer in 1873.

When the War Department ordered all Lakota bands onto their reservations in 1876, Crazy Horse became a leader of the resistance. Closely allied to the Cheyenne through his first marriage to a Cheyenne woman, he gathered a force of 1,200 Oglala and Cheyenne at his village and turned back General George Crook on June 17, 1876, as Crook tried to advance up Rosebud Creek toward Sitting Bull's encampment on the Little Bighorn.

After this victory, Crazy Horse joined forces with Sitting Bull and on June 25 led his band in the counterattack that destroyed Custer's Seventh Cavalry, flanking the Americans from the north and west as Hunkpapa warriors led by chief Gall charged from the south and east.

Following the Lakota victory at the Little Bighorn, Sitting Bull and Gall retreated to Canada, but Crazy Horse remained to battle General Nelson Miles as he pursued the Lakota and their allies relentlessly throughout the winter of 1876-77. This constant military harassment and the decline of the buffalo population eventually forced Crazy Horse to surrender on May 6, 1877; except for Gall and Sitting Bull, he was the last important chief to yield.

Even in defeat, Crazy Horse remained an independent spirit, and in September 1877, when he left the reservation without authorization, to take his sick wife to her parents, General George Crook ordered him arrested, fearing that he was plotting a return to battle. Crazy Horse did not resist arrest at first, but when he realized that he was being led to a guardhouse, he began to struggle, and while his arms were held by one of the arresting officers, a soldier ran him through with a bayonet.

The Dakota are first recorded to have resided at the source of the Mississippi River during the seventeenth century. By 1700 some had migrated to present-day South Dakota. Late in the 17th century, the Dakota entered into an alliance with French merchants. The French were trying to gain advantage in the struggle for the North American fur trade against the English, who had recently established the Hudson's Bay Company.

Siege of New Ulm, August 19, 1862

By 1862, shortly after a failed crop the year before and a winter starvation, the federal payment was late. The local traders would not issue any more credit to the Santee and one trader, Andrew Myrick, went so far as to say, "If they're hungry, let them eat grass." On August 17, 1862 the Dakota War began when a few Santee men murdered a white farmer and most of his family. They inspired further attacks on white settlements along the Minnesota River. The Santee attacked the trading post. Later settlers found Myrick among the dead with his mouth stuffed full of grass.

On November 5, 1862 in Minnesota, in courts-martial, 303 Santee Sioux were found guilty of rape and murder of hundreds of American settlers. They were sentenced to be hanged. No attorneys or witness were allowed as a defense for the accused, and many were convicted in less than five minutes of court time with the judge. President Abraham Lincoln commuted the death sentence of 284 of the warriors, while signing off on the execution of 38 Santee men by hanging on December 26, 1862 in Mankato, Minnesota. It was the largest mass-execution in U.S. history.

Afterwards, the US suspended treaty annuities to the Dakota for four years and awarded the money to the white victims and their families. The men remanded by order of President Lincoln were sent to a prison in Iowa, where more than half died.

During and after the revolt, many Santee and their kin fled Minnesota and Eastern Dakota to Canada, or settled in the James River Valley in a short-lived reservation before being forced to move to Crow Creek Reservation on the east bank of the Missouri. A few joined the Yanktonai and moved further west to join with the Lakota bands to continue their struggle against the United States military.

Others were able to remain in Minnesota and the east, in small reservations existing into the 21st century, including Sisseton-Wahpeton, Flandreau, and Devils Lake (Spirit Lake or Fort Totten) Reservations in the Dakotas. Some ended up in Nebraska, where the Santee Sioux Tribe today has a reservation on the south bank of the Missouri.

Those who fled to Canada now have descendants residing on nine small Dakota Reserves, five of which are located in Manitoba (Sioux Valley, Long Plain, Dakota Tipi, Birdtail Creek, and Oak Lake [Pipestone]) and the remaining four (Standing Buffalo, Moose Woods White Cap] Round Plain [Wahpeton], and Wood Mountain) in Saskatchewan.

The Great Sioux War comprised a series of battles between the Lakota and allied tribes such as the Cheyenne against the United States military. The earliest engagement was the Battle of Powder River, and the final battle was the Wolf Mountain. Included are the Battle of the Rosebud, Battle of the Little Bighorn, Battle of Warbonnet Creek, Battle of Slim Buttes, Battle of Cedar Creek, and the Dull Knife Fight.

The massacre at Wounded Knee Creek was the last major armed conflict between the Lakota and the United States. It was described as a "massacre" by General Nelson A. Miles in a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

On December 29, 1890, five hundred troops of the U.S. 7th Cavalry, supported by four Hotchkiss guns (a lightweight artillery piece capable of rapid fire), surrounded an encampment of the Lakota bands of the Miniconjou and Hunkpapa with orders to escort them to the railroad for transport to Omaha, Nebraska.

By the time it was over, 25 troopers and more than 150 Lakota Sioux lay dead, including men, women, and children. Some of the soldiers are believed to have been the victims of "friendly fire" because the shooting took place at point-blank range in chaotic conditions. Around 150 Lakota are believed to have fled the chaos, many of whom may have died from hypothermia.

Later in the 19th century, the railroads hired hunters to exterminate the buffalo herds, the Indians' primary food supply. The Santee and Lakota were forced to accept white-defined reservations in exchange for the rest of their lands, and domestic cattle and corn in exchange for buffalo. They became dependent upon annual federal payments guaranteed by treaty.

In Minnesota, the treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota in 1851 left the Sioux with a reservation twenty miles (32 km) wide on each side of the Minnesota River. Today, one half of all enrolled Sioux in the United States live off the reservation. Enrolled members in any of the Sioux tribes in the United States are required to have ancestry that is at least 1/4 degree Sioux (the equivalent to one grandparent).

In Canada, the Canadian government recognizes the tribal community as First Nations. The land holdings of the these First Nations are called Indian Reserves.

The Wounded Knee incident began February 27, 1973 when about 200 Oglala Lakota and followers of the American Indian Movement seized and occupied the town of Wounded Knee, South Dakota on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. The grassroots protest followed the failure of their effort to impeach the elected tribal president Richard Wilson, whom they accused of corruption and abuse of opponents; they also protested the United States government's failure to fulfill treaties with Indian peoples and demanded the reopening of treaty negotiations.

Oglala and AIM activists controlled the town for 71 days while the United States Marshals Service, Federal Bureau of Investigation agents and other law enforcement agencies cordoned off the area. The activists chose the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre for its symbolic value. Both sides were armed and shooting was frequent. An FBI agent was paralyzed from a gunshot wound early during the occupation, and later died from complications; a Cherokee and an Oglala Lakota were killed by shootings in April 1973. Ray Robinson, a civil rights activist who joined the protesters, disappeared during the events and is believed to have been murdered. Due to damage to the houses, the small community was never reoccupied.

The occupation attracted wide media coverage, especially after the press accompanied the two US Senators from South Dakota to Wounded Knee. The events electrified American Indians, who were inspired by the sight of their people standing in defiance of the government which had so often failed them. Many Indian supporters traveled to Wounded Knee to join the protest. At the time there was widespread public sympathy for the goals of the occupation, as Americans were becoming more aware of longstanding issues of injustice related to American Indians. Afterward AIM leaders Dennis Banks and Russell Means were indicted on charges related to the events, but their 1974 case was dismissed by the federal court for prosecutorial misconduct, a decision upheld on appeal.

Wilson stayed in office and in 1974 was re-elected amid charges of intimidation, voter fraud and other abuses. The rate of violence climbed on the reservation as conflict opened between political factions in the following three years; residents accused Wilson's private militia, Guardians of the Oglala Nation (GOONs), for much of it. More than 60 opponents of the tribal government died violently during those years, including the executive director of the Oglala Sioux Civil Rights Organization (OSCRO). In 1975 in the "Pine Ridge shootout", two FBI agents were killed, found to have been shot at close range.

Three AIM members were indicted for their deaths, including Leonard Peltier, who escaped to Canada. In the first trial, the two AIM members were acquitted. Because of delays of the extradition process, Peltier was tried separately; he was convicted in a controversial case. Anna Mae Aquash, the highest-ranking woman in AIM, was murdered in late December 1975 at the reservation, but her body was not found until February 1976. Two Native American men were convicted in 2004 and 2010 in her murder, but many people believe that the execution was ordered by the highest leaders in AIM.

The Republic of Lakotah or Lakotah is a proposed country in North America to serve as a homeland for the Lakota. Its boundaries would be surrounded by the borders of the United States, covering thousands of square miles in North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Wyoming, and Montana. The proposed borders are those of the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie between the United States government and the Lakota.

A group of Native Americans called the Lakota Freedom Delegation traveled to Washington, D.C., on 17 December 2007 and delivered a statement asserting the independence of the Lakota from the United States. The group argues that the recent declaration of independence is not a secession from the USA, but rather a reassertion of sovereignty. Their leader is Russell Means, one of the prominent members of the American Indian Movement in the late 1960s and 1970s.

The Lakota Freedom Delegation does not recognize tribal governments or presidents as recognized by the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs, sometimes referring to these groups as "stay-by-the-fort Indians".

The claimed boundaries of Lakotah are the Yellowstone River to the north, the North Platte River to the south, the Missouri River to the east and an irregular line marking the west. These borders coincide with those set by the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

By these claims, the largest city in Lakotah is Omaha, Nebraska. The boundaries also contain Rapid City, South Dakota; Mandan, North Dakota; Casper, Wyoming; and Bellevue, Nebraska as well as Mount Rushmore.

In addition to containing all the Indian reservations of the Lakota, the territory which the Republic claims includes reservations inhabited by non-Lakota Siouan peoples (the Dakota Indian Reservation, the Winnebago Indian Reservation and the Omaha Indian Reservation) as well as part of one non-Sioux reservation (the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in western North Dakota). Lakota would also contain the poorest counties in the United States.

On January 1, 2008, the Republic announced they were filing liens on all US government-held lands within their claimed borders; however, the first round of liens, in an unnamed county in South Dakota, were rejected.

Following this it chose to concentrate on recovery of the Black Hills.

In July 2008, Russell Means announced that the Republic of Lakotah would be founding an all-Lakota "grand jury" to investigate corruption by US government officials on the seven reservations in the Republic's claimed territory.

Means ran for presidency of the Oglala Lakota in 2008 election, losing by 1,918 to 2,277.

The Keeping of the Soul

Inipi:The Rite of Purification

Hanblecheyapi:Crying for a Vision

Wiwanyag Wachipi:The Sun Dance

Hunkapi:The Making of Relatives

Ishna Ta Awi Cha Lowan:Preparing a Girl for Womanhood

Tapa Wanka Yap:Throwing of the Ball

In the beginning, prior to the creation of the Earth, the gods resided in an undifferentiated celestial domain and humans lived in an indescribably subterranean world devoid of culture.

Chief among the gods were Takushkanshkan ("something that moves"), the Sun, who is married to the Moon, with whom he has one daughter, Wohpe ("falling star"); Old Man and Old Woman, whose daughter Ite ("face") is married to Wind, with whom she has four sons, the Four Winds.

Among numerous other spirits, the most important is Inktomi ("spider"), the devious trickster. Inktomi conspires with Old Man and Old Woman to increase their daughter's status by arranging an affair between the Sun and Ite. The discovery of the affair by the Sun's wife leads to a number of punishments by Takuskanskan, who gives the Moon her own domain, and by separating her from the Sun initiates the creation of time.

Old Man, Old Woman, and Ite are sent to earth, but Ite is separated from the Wind, her husband, who, along with the Four Winds and a fifth wind presumed to be the child of the adulterous affair, establishes space. The daughter of the Sun and the Moon, Wohpe, also falls to earth and later resides with the South Wind, the paragon of Lakota maleness, and the two adopt the fifth wind, called Wamniomni ("whirlwind").

The Emergence

Alone on the newly formed earth, some of the gods become bored, and Ite prevails upon Inktomi to find her people, the Buffalo Nation. In the form of a wolf, Inktomi travels beneath the earth and discovers a village of humans. Inktomi tells them about the wonders of the earth and convinces one man, Tokahe ("the first"), to accompany him to the surface.

Tokahe does so and upon reaching the surface through a cave (Wind Cave in the Black Hills), marvels at the green grass and blue sky. Inktomi and Ite introduce Tokahe to buffalo meat and soup and show him tipis, clothing, and hunting utensils. Tokahe returns to the subterranean village and appeals to six other men and their families to travel with him to the earth's surface.

When they arrive, they discover that Inktomi has deceived them: buffalo are scarce, the weather has turned bad, and they find themselves starving. Unable to return to their home, but armed with a new knowledge about the world, they survive to become the founders of the Seven Fireplaces.

The Seven Sacred Rites

Wohpe ("Falling Star") appears to the Lakota as a real woman during a period of starvation. She is discovered by two hunters, one of whom lusts for her. He is immediately covered by a mist and reduced to bones. The other hunter is instructed to return to his camp and tell the chief and people that she, "White Buffalo Calf Woman," will appear to them the next day. He obeys, and a great council tipi is constructed.

White Buffalo Calf Woman presents to the people a bundle containing the sacred pipe, and she tells them that in time of need they should smoke from the pipe and pray to Wakantanka for help. The smoke from the pipe will carry their prayers upward.

She then instructs them in the seven sacred rites, most of which continue to form the basis of Lakota religion, including the sweat lodge, the vision quest, and the Sundance Day.