Baths - Thermae, Baths of - Caracalla, Diocletian, Trajan

Circus, Circus Maximus, Hippodrome

Ancient Roman architecture adopted certain aspects of Ancient Greek architecture, creating a new architectural style. The Romans were indebted to their Etruscan neighbors and forefathers who supplied them with a wealth of knowledge essential for future architectural solutions, such as hydraulics and in the construction of arches. Later they absorbed Greek and Phoenician influence, apparent in many aspects closely related to architecture; for example, this can be seen in the introduction and use of the Triclinium in Roman villas as a place and manner of dining.

Roman architecture flourished throughout the Empire during the Pax Romana - the long period of relative peace and minimal expansion by military force experienced by the Roman Empire in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Since it was established by Caesar Augustus it is sometimes called Pax Augusta. Its span was about 207 years (27 BC to 180 AD).

Factors such as wealth and high population densities in cities forced the ancient Romans to discover new (architectural) solutions of their own. The use of vaults and arches, together with a sound knowledge of building materials, enabled them to achieve unprecedented successes in the construction of imposing structures for public use.

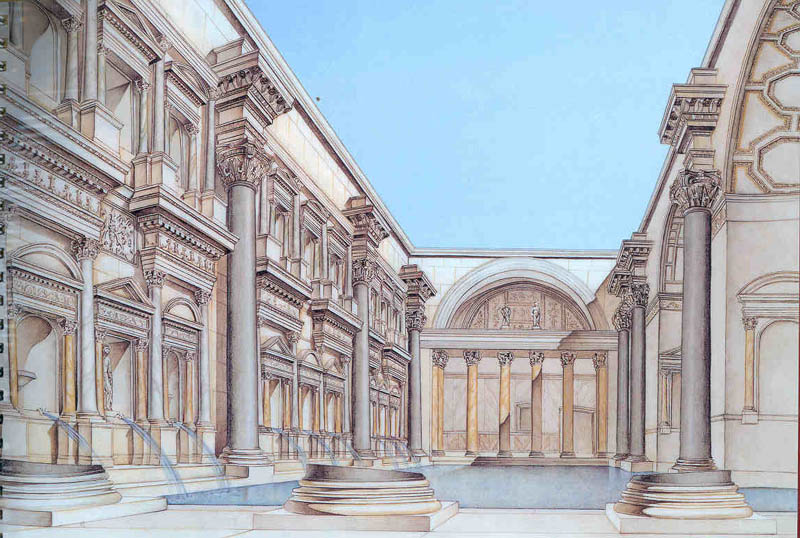

Baths of Caracalla

Examples include the Aqueducts of Rome, the Baths of Diocletian and the Baths of Caracalla, the basilicas and Colosseum. They were reproduced at smaller scale in most important towns and cities in the Empire. Some surviving structures are almost complete, such as the town walls of Lugo in Hispania Tarraconensis, or northern Spain.

The Ancient Romans intended that public buildings should be made to impress, as well as perform a public function. The Romans did not feel restricted by Greek aesthetic axioms alone in order to achieve these objectives.

The Pantheon is a example of this, particularly in the version rebuilt by Hadrian, which remains perfectly preserved, and which over the centuries has served, particularly in the Western Hemisphere, as the inspiration for countless public buildings.

The same emperor left his mark on the landscape of northern Britain when he built a wall to mark the limits of the empire, and after further conquests in Scotland, the Antonine wall was built to replace Hadrian's Wall.

Political propaganda demanded that these buildings should be made to impress as well as perform a public function. The Romans didn't feel restricted by Greek aesthetic axioms alone in order to achieve these objectives. The Pantheon is a supreme example of this, particularly in the version rebuilt by Hadrian and which still stands in its celestial glory as a prototype of several other great buildings of Western architecture. The same emperor left his mark on the landscape of northern Britain when he built a wall to mark the limits of the empire, and after further conquests in Scotland, the Antonine wall was built to replace Hadrian's Wall.

Factors such as wealth and high population densities in cities forced the ancient Romans to discover new (architectural) solutions of their own. The use of vaults and arches, together with a sound knowledge of building materials, enabled them to achieve unprecedented successes in the construction of imposing structures for public use.

The Roman use of the arch together with their improvements in the use of concrete and construction of vaulted ceilings also enabled huge (covered) public spaces such as the public baths and basilicas. The Romans also based much of their architecture on the dome, such as Hadrian's Pantheon in the city of Rome, and the Baths of Diocletian.

Art historians such as Gottfried Richter in the 20's identified the Roman architectural innovation as being the Triumphal Arch and it is poignant to see how this symbol of power on earth was transformed and utilized within the Christian basilicas when the Roman Empire of the West was on its last legs: The arch was set before the altar to symbolize the triumph of Christ and the after life. It is in their impressive aqueducts that we see the arch triumphant, especially in the many surviving examples, such as the Pont du Gard, the aqueduct at Segovia and the remains of the Aqueducts of Rome itself. Their survival is testimony to the durability of their materials and design.

On a less visible level for the modern observer, ancient Roman developments in housing and public hygiene are impressive, especially given their day and age. Clear examples are baths and latrines which could be either public or private, not to mention developments in under-floor heating, in the form of the hypocaust, double glazing (examples in Ostia) and piped water (examples in Pompeii).

Possibly most impressive from an urban planning point of view were the multi-story apartment blocks called insulae built to cater for a wide range of situations. These buildings solely intended as large scale accommodation could reach several floors in height. Although they were often dangerous, unhealthy and prone to fires there are examples in cities such as the Roman port town of Ostia which date back to the reign of Trajan and point to solutions which catered for a variety of needs and markets.

As an example of this we have the housing on Via della Foce: large scale real estate development made to cater for up-and-coming middle class entrepreneurs. Rather like modern semi-detached housing these had repeated floor plans intended to be easily and economically built in a repetitive fashion. Internal spaces were designed to be relatively low-cost yet functional and with decorative elements reminiscent of the detached houses and villas to which the buyers might aspire in their later years. Each apartment had its own terrace and private entrance. External walls were in "Opus Reticulatum" whilst interiors in "Opus Incertum" which would then be plastered and possibly painted. Some existing examples show alternate red and yellow painted panels to have been a relatively popular choice of interior decor.

Roman architecture was sometimes determined based upon the requirements of Roman religion. For example the Pantheon was an amazing engineering feat created for religious purposes, and its design (the large dome and open spaces) were made to fit the requirements of the religious services.

Innovation started in the first century BC, with the invention of concrete, a strong and readily available substitute for stone. Tile-covered concrete quickly supplanted marble as the primary building material and more daring buildings soon followed, with great pillars supporting broad arches and domes rather than dense lines of columns suspending flat architraves. The freedom of concrete also inspired the colonnade screen, a row of purely decorative columns in front of a load-bearing wall. In smaller-scale architecture, concrete's strength freed the floor plan from rectangular cells to a more free-flowing environment. Most of theses developments are ably described by Vitruvius writing in the first century AD.

Although concrete had been used on a minor scale in Mesopotamia, Roman architects perfected it and used it in buildings where it could stand on its own and support a great deal of weight. The first use of concrete by the Romans was in the town of Cosa sometime after 273 BC. Ancient Roman concrete (opus cementicium) was a mixture of lime mortar, sand, water, and stones. The ancient builders placed these ingredients in wooden frames where it hardened and bonded to a facing of stones or (more frequently) bricks. When the framework was removed, the new wall was very strong with a rough surface of bricks or stones. This surface could be smoothed and faced with an attractive stucco or thin panels of marble or other colored stones called revetment. Concrete construction proved to be more flexible and less costly than building solid stone buildings. The materials were readily available and not difficult to transport. The wooden frames could be used more than once, allowing builders to work quickly and efficiently.

On return from campaigns in Greece, the general Sulla returned with what is probably the most well-known element of the early imperial period: the mosaic, a decoration of colorful chips of stone inset into cement. This tiling method took the empire by storm in the late first century and the second century and in the Roman home joined the well known mural in decorating floors, walls, and grottoes in geometric and pictorial designs.

Though most would consider concrete the Roman contribution most relevant to the modern world, the Empire's style of architecture, though no longer used with any great frequency, can still be seen throughout Europe and North America in the arches and domes of many governmental and religious buildings.

Tile covered concrete quickly supplanted marble as the primary building material and more daring buildings soon followed, with great pillars supporting broad arches and domes rather than dense lines of columns suspending flat architraves. The freedom of concrete also inspired the colonnade screen, a row of purely decorative columns in front of a load-bearing wall. In smaller-scale architecture, concrete's strength freed the floor plan from rectangular cells to a more free-flowing environment. Most of these developments are described by Vitruvius writing in the first century AD in his work De Architectura.

Roman architects invented Roman concrete and used it in buildings where it could stand on its own and support a great deal of weight. The first use of concrete by the Romans was in the town of Cosa sometime after 273 BCE. Ancient Roman concrete was a mixture of lime mortar, sand with stone rubble, pozzolana, water, and stones, and stronger than previously-used concrete. The ancient builders placed these ingredients in wooden frames where it hardened and bonded to a facing of stones or (more frequently) bricks.

When the framework was removed, the new wall was very strong with a rough surface of bricks or stones. This surface could be smoothed and faced with an attractive stucco or thin panels of marble or other colored stones called revetment. Concrete construction proved to be more flexible and less costly than building solid stone buildings. The materials were readily available and not difficult to transport. The wooden frames could be used more than once, allowing builders to work quickly and efficiently.

On return from campaigns in Greece, the general Sulla returned with what is probably the most well-known element of the early imperial period: the mosaic, a decoration of colourful chips of stone inset into cement. This tiling method took the empire by storm in the late first century and the second century and in the Roman home joined the well known mural in decorating floors, walls, and grottoes in geometric and pictorial designs.

Though most would consider concrete the Roman contribution most relevant to the modern world, the Empire's style of architecture can still be seen throughout Europe and North America in the arches and domes of many governmental and religious buildings.

Today, Roman influence can be seen among countless buildings such as banks, government buildings, houses, business buildings, etc. Roman culture resonates among modern building styles because of the structural mastering of the dome and the arch. When a building has substantial weight bearing down on lower levels, columns can easily support the weight when it is distributed through an arch, reducing the stress significantly. The arch, for this reason, is the most famous and most modernly used aspect of Roman architecture and can be seen nearly anywhere.

The Dome is not used as frequently among modern buildings, but it is widely used to show prominence and elegance. In Washington, D.C., domes are a common theme among the government buildings, originally meant to imitate the grandeur of ancient Rome. Modern use of Ancient Roman Architecture is most commonly used as an allusion to Ancient Rome itself, people recall the Roman Empire as a colossal, dominant, and extremely influential nation. To allude to Ancient Rome is to project the image of greatness and influence.