Chinchorro - Mummies of Chile

Some of the best-preserved mummies date from the Inca period in Peru and Chile some 500 years ago, where children were ritually sacrificed and placed on the summits of mountains in the Andes. Also found in this area are the Chinchorro mummies, which are among the oldest mummified bodies ever found. The cold, dry climate had the effect of desiccating the corpses and preserving them intact. In 1995, the frozen body of a 12- to 14-year-old Inca girl who had died some time between 1440 and 1450 was discovered on Mount Ampato in southern Peru. Known as "Mummy Juanita" ("Momia Juanita" in Spanish) or "The Ice Maiden", some archaeologists believe that she was a human sacrifice to the Inca mountain god Apus.

Chinchorro - Mummies of Chile

The Chinchorro mummies are mummified remains of individuals from the South American Chinchorro culture found in what is now northern Chile and southern Peru. They are the oldest examples of mummified human remains, dating to thousands of years before the Egyptian mummies. They are believed to have first appeared around 5000 B.C. and reaching a peak around 3000 B.C.

Often Chinchorro mummies were elaborately prepared by removing the internal organs and replacing them with vegetable fibers or animal hair. In some cases an embalmer would remove the skin and flesh from the dead body and replace them with clay. Shell midden and bone chemistry suggest that 90% of their diet was seafood. Many ancient cultures of fisherfolk existed, tucked away in the arid river valleys of the Andes, but the Chinchorro made themselves unique by their dedicated preservation of the dead.

The Chinchorro mummies are significant because during the periods of these mummies, everyone who died was mummified, including children, new-borns and fetuses. This shows that it was not reserved for those of high rank or high status - mummification was not a sign of social stratification.

Radiocarbon dating reveals that the oldest, discovered Chinchorro mummy was that of a child from a site in the Camarones Valley, about 60 miles south of Arica and dates from around 5050 B.C. The mummies continued to be made until about 1800 B.C., making them contemporary with Las Vegas culture and Valdivia culture in Ecuador and the Norte Chico civilization in Peru.

The Chinchorro mummies are the earliest examples of the deliberate preservation of the dead. The mummies may have served as a means of assisting the soul in surviving, and to prevent the bodies from frightening the living.

Chinchorro Mummification

While many cultures throughout the world have sought to preserve the dead elite, the Chinchorro tradition performed mummification on all members of their society, including children and miscarried fetuses. Because of this egalitarian preservation of the dead, hundreds of mummies have been excavated and hundreds more remain. The oldest mummies recovered from the Atacama Desert are dated between 6000 BC and 5000 BC, the oldest yet found. To put this in perspective, the earliest mummy that has been found in Egypt dated around 3000 BC.

Preparation of mummies

The manner in which the Chinchorro mummified their dead changed over the years, but several traits remained constant throughout their history. In excavated mummies, the skin had been set aside and all soft tissues and organs, including the brain, had been removed from the corpse. There is even evidence that the bone marrow was removed from the femurs of one mummy, but this has not yet been identified as a frequent occurrence. After the soft tissues had been removed, the bones were reinforced with sticks and the skin was stuffed with vegetable matter before reassembling the corpse. The mummy was then given a clay mask, though some mummies were completely covered in clay, wrapped in reeds and left to dry out for 30 - 40 days.

Techniques

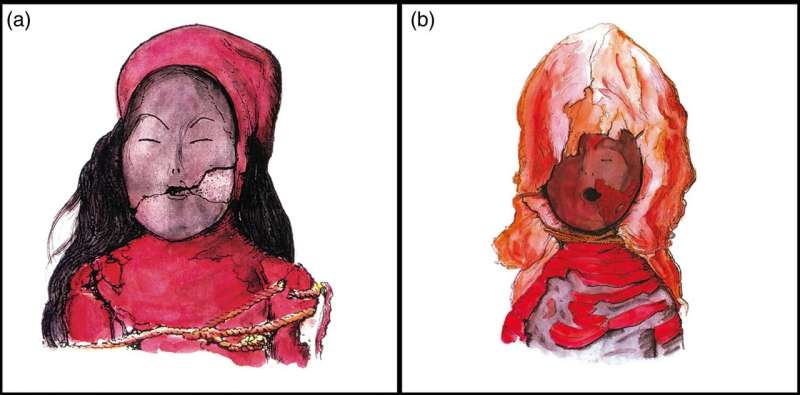

The two most common techniques used in Chinchorro mummification were the Black mummies and the Red mummies. The Black mummy technique (5000 B.C. to 3000 B.C.) involved taking the dead person's body apart, treating it, and reassembling it. The head, arms and legs were removed; the skin was often removed, too. The body was heat-dried, and the flesh and tissue were completely stripped from the bone. After reassembly, the body was then covered with a white ash paste, filling the nooks and crannies left by the reassembling process. The paste was also used to fill out the person's normal facial features. The person's skin (including facial skin with a wig attachment of short black human hair) was refitted on the body, sometimes in smaller pieces, sometimes in one almost-whole piece. Sometimes sea lion skin was used as well. Then the skin (or, in the case of children, who were often missing their skin layer, the white ash layer) was painted with manganese giving them a black color.

The Red mummy technique (2500 BC to 2000 BC) was a technique in which rather than disassemble the body, many incisions were made in the trunk and shoulders to remove internal organs and dry the body cavity. The head was cut from the body so that the brain could be removed. The body was packed with various materials to return it to somewhat more-normal dimensions, sticks used to strengthen it, and the incisions sewn up. The head was placed back on the body, this time with a wig made from tassels of human hair up to 60 cm long. A "hat" made out of clack clay held the wig in place. Except for the wig and often the (black) face, everything was then painted with red ochre.

1,100-year-old mummy found in Chile died of extensive injuries when a turquoise mine caved in, CT scans reveal Live Science - January 9, 2026

Extensive evidence of blunt-force trauma discovered on the man's skeleton suggests he died because of a rockfall or mine collapse, according to a new study

Chinchorro mummification may have originated as a form of art therapy, study suggests PhysOrg - December 26, 2025

The Chinchorro were a highly dynamic group of skilled fishers, artisans, and morticians who lived along the coast of the Atacama Desert in Chile. They are best known for their characteristic artificial mummies, which were produced between 7000 and 3500 BP.

Origin of 'six-inch mummy' confirmed BBC - March 22, 2018

Tests on a six-inch-long mummified skeleton from Chile confirm that it represents the remains of a newborn with multiple mutations in key genes. Despite being the size of a fetus, initial tests had suggested the bones were of a child aged six to eight. These highly unusual features prompted wild speculation about its origin. Now, DNA testing indicates that the estimated age of the bones and other anomalies may have been a result of the genetic mutations. In addition to its exceptionally small height, the skeleton had several unusual physical features, such as fewer than expected ribs and a cone-shaped head. The remains were initially discovered in a pouch in the abandoned nitrate mining town of La Noria. From there, they found their way into a private collection in Spain. Some wondered whether the remains, dubbed Ata after the Atacama region where they were discovered, could in fact be the remains of a non-human primate. A documentary, called Sirius, even suggested it could be evidence of alien visitations.

Scans unveil secrets of world's oldest mummies PhysOrg - December 24, 2016

More than 7,000 years after they were embalmed by the Chinchorro people, an ancient civilization in modern-day Chile and Peru, 15 mummies were taken to a Santiago clinic last week to undergo DNA analysis and computerized tomography scans. The Chinchorro were a hunting and fishing people who lived from 10,000 to 3,400 BC on the Pacific coast of South America, at the edge of the Atacama desert. They were among the first people in the world to mummify their dead. Their mummies date back some 7,400 years at least 2,000 years older than Egypt's.

Incan Child Sacrificed to the Gods Reveals History of American Expansion Live Science - November 12, 2015

The mummy of an Incan child who was sacrificed to the gods more than 500 years ago belonged to a previously unknown offshoot of an ancient Native American lineage, new research finds. The child, a 7-year-old who was found frozen in the highest reaches of the Andes in Argentina, was part of a genetic lineage that arose when humans were beginning to cross the Bering Strait or first migrating into the Americas, the researchers found.

Lost genetic history of Inca child mummy BBC - November 12, 2015

Scientists have unravelled part of the genetic code of a child who was sacrificed in a ritual ceremony by the Inca civilization 500 years ago. The boy's mummified remains were discovered on an Argentinean mountain. Analysis of his mitochondrial DNA, which is passed from mother to child, showed that the boy's closest living relatives are in Peru and Bolivia. He belonged to a population of native South Americans that almost disappeared after the Spanish conquest. Researchers in Spain were given permission to extract mitochondrial DNA from the seven-year-old boy to study part of his genome. By comparing his genetic code with hundreds of thousands of samples held in genetic databases, they found his genetic profile was very rare.

Saving Chilean mummies from climate change Science Daily - March 9, 2015

At least two thousand years before the ancient Egyptians began mummifying their pharaohs, a hunter-gatherer people called the Chinchorro living along the coast of modern-day Chile and Peru developed elaborate methods to mummify not just elites but all types of community members--men, women, children, and even unborn fetuses. Radiocarbon dating as far back as 5050 BC makes them the world's oldest human-made mummies. But after staying remarkably well preserved for millennia, during the past decade many of the Chinchorro mummies have begun to rapidly degrade. To discover the cause, and a way to stop the deterioration, Chilean preservationists turned to a Harvard scientist with a record of solving mysteries around threatened cultural heritage artifacts.

Nearly 120 Chinchorro mummies are housed in the collection of the University of Tarapaca's archeological museum in Arica, Chile. That's where scientists noticed that the mummies were starting to visibly degrade at an alarming rate. In some cases, specimens were literally turning into a black ooze.

Chilean Mummies Reveal Signs of Arsenic Poisoning Live Science - April 15, 2014

People of numerous pre-Columbian civilizations in northern Chile, including the Incas and the Chinchorro culture, suffered from chronic arsenic poisoning due to their consumption of contaminated water, new research suggests. Previous analyses showed high concentrations of arsenic in the hair samples of mummies from both highland and coastal cultures in the region. However, researchers weren't able to determine whether the people had ingested arsenic or if the toxic element in the soil had diffused into the mummies' hair after they were buried. In the new study, scientists used a range of high-tech methods to analyze hair samples from a 1,000- to 1,500-year-old mummy from the Tarapaca Valley in Chile's Atacama Desert. They determined the high concentration of arsenic in the mummy's hair came from drinking arsenic-laced water and, possibly, eating plants irrigated with the toxic water.

Chilean Mummies Reveal Ancient Nicotine Habit Live Science - June 28, 2013

The hair of mummies from the town of San Pedro de Atacama in Chile reveals the people in the region had a nicotine habit spanning from at least 100 B.C. to A.D. 1450. Additionally, nicotine consumption occurred on a society-wide basis, irrespective of social status and wealth, researchers say. The finding refutes the popular view that the group living in this region smoked tobacco for just a short stint before moving on to snuffing hallucinogens.

Chilean team proposes theory on why early culture began to mummify their dead PhysOrg - August 14, 2012

Marqueta et al, hypothesized that the Chinchorro, hunter-gatherers that lived in the desert region of what is now northern Chile and southern Peru, from about 10,000 years ago to around 4,000 years ago, began mummifying their dead as a way to deal with the bodies of those that had passed on, but refused to decompose. The bodies wouldnÕt decompose because it was simply too dry; the area is one of the driest places on Earth. Thus over time, because the Chinchorro buried their dead in shallow graves, the wind would partially uncover them, leaving those still alive to be constantly exposed to thousands of such bodies in their lifetime. But that was only part of the story they say.