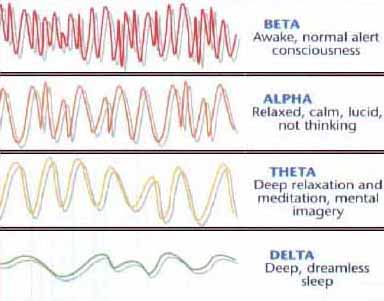

The brain is an electrochemical organ (machine) using electromagnetic energy to function. Electrical activity emanating from the brain is displayed in the form of brainwaves. They range from the high amplitude, low frequency delta to the low amplitude, high frequency beta. During meditation brain waves alter.

The four categories of these brainwaves:

Beta Waves or beta rhythm, is the term used to designate the frequency range of human brain activity between 12 and 30 Hz (12 to 30 transitions or cycles per second). They awaking awareness, extroversion, concentration, logical thinking, active conversation.

Alpha Waves are electromagnetic oscillations in the frequency range of 8–12 Hz arising from synchronous and coherent (in phase / constructive) electrical activity of thalamic pacemaker cells in humans. They are also called Berger's wave in memory of the founder of EEG. They place the brain in states of relaxation times, non-arousal, meditation, hypnosis

Theta Waves is an oscillatory pattern in EEG signals recorded either from inside the brain or from electrodes glued to the scalp. They are found in day dreaming, dreaming, creativity, meditation, paranormal phenomena, out of body experiences, ESP, shamanic journeys.

A person driving on a freeway, who discovers that they can't recall the last five miles, is often in a theta state - induced by the process of freeway driving. This can also occur in the shower or tub or even while shaving or brushing your hair. It is a state where tasks become so automatic that you can mentally disengage from them. The ideation that can take place during the theta state is often free flow and occurs without censorship or guilt. It is typically a very positive mental state.

Delta Waves are high amplitude brain waves with a frequency of oscillation between 0–4 hertz. Delta waves, like other brain waves, are recorded with an electroencephalogram (EEG) and are usually associated with the deepest stages of sleep (3 and 4 NREM), also known as slow-wave sleep (SWS), and aid in characterizing the depth of sleep.

Meditation increases activity in the left prefrontal cortex. The changes are stable over time. If you stop meditating for a while, the effect lingers.

The brain processes through Binary Code

Evidence Builds That Meditation Strengthens the Brain Science Daily - March 15, 2012

Earlier evidence out of UCLA suggested that meditating for years thickens the brain (in a good way) and strengthens the connections between brain cells. Now a further report by UCLA researchers suggests yet another benefit. Long-term meditators have larger amounts of gyrification ("folding" of the cortex, which may allow the brain to process information faster) than people who do not meditate. A direct correlation was found between the amount of gyrification and the number of meditation years, possibly providing further proof of the brain's neuroplasticity, or ability to adapt to environmental changes.

Is meditation the push-up for the brain? PhysOrg - July 14, 2011

Two years ago, researchers at UCLA found that specific regions in the brains of long-term meditators were larger and had more gray matter than the brains of individuals in a control group. This suggested that meditation may indeed be good for all of us since, alas, our brains shrink naturally with age.

How Meditation May Change the Brain New York Times - January 28, 2011

The researchers report that those who meditated for about 30 minutes a day for eight weeks had measurable changes in gray-matter density in parts of the brain associated with memory, sense of self, empathy and stress.

Brain Waves and Meditation Science Daily - March 31, 2010

Forget about crystals and candles, and about sitting and breathing in awkward ways. Meditation research explores how the brain works when we refrain from concentration, rumination and intentional thinking. Electrical brain waves suggest that mental activity during meditation is wakeful and relaxed.

Meditation increases brain gray matter PhysOrg - May 13, 2009

Push-ups, crunches, gyms, personal trainers -- people have many strategies for building bigger muscles and stronger bones. But what can one do to build a bigger brain? Meditate.

Meditation found to increase brain size PhysOrg - January 31, 2006

People who meditate grow bigger brains than those who don't. Researchers at Harvard, Yale, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have found the first evidence that meditation can alter the physical structure of our brains. Brain scans they conducted reveal that experienced meditators boasted increased thickness in parts of the brain that deal with attention and processing sensory input.

Meditation builds up the brain New Scientist - November 15, 2005

Meditating does more than just feel good and calm you down, it makes you perform better - and alters the structure of your brain, researchers have found. People who meditate say the practice restores their energy, and some claim they need less sleep as a result. Many studies have reported that the brain works

Meditation Shown to Light Up Brains of Buddhists Yahoo - May 2003

Using new scanning techniques, neuroscientists have discovered that certain areas of the brain light up constantly in Buddhists, which indicates positive emotions and good mood. "We can now hypothesize with some confidence that those apparently happy, calm Buddhist souls one regularly comes across in places such as Dharamsala, India, really are happy,"

Professor Owen Flanagan, of Duke University in North Carolina, said. Dharamsala is the home base of exiled Tibetan leader the Dalai Lama. The scanning studies by scientists at the University of Wisconsin at Madison showed activity in the left prefrontal lobes of experienced Buddhist practitioners. The area is linked to positive emotions, self-control and temperament.

Other research by Paul Ekman, of the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, suggests that meditation and mindfulness can tame the amygdala, an area of the brain which is the hub of fear memory. Ekman discovered that experienced Buddhists were less likely to be shocked, flustered, surprised or as angry as other people. Flanagan believes that if the findings of the studies can be confirmed they could be of major importance.

Meditation mapped in Monks BBC - March 1, 2002

During meditation, people often feel a sense of no space. Scientists investigating the effect of the meditative stateon Buddhist monk's brains have found that portions ofthe organ previously active become quiet, whilst pacified areas become stimulated. Using a brain imaging technique, Dr. Newberg and his team studied a group of Tibetan Buddhist monks as they meditated for approximately one hour. When they reached a transcendental high, they were asked to pull a kite string to their right, releasing an injection of a radioactive tracer. By injecting a tiny amount of radioactive marker into the bloodstream of a deep meditator, the scientists soon saw how the dye moved to active parts of the brain.

Study shows compassion meditation changes the brain PhysOrg - March 27, 2008

Can we train ourselves to be compassionate? A new study suggests the answer is yes. Cultivating compassion and kindness through meditation affects brain regions that can make a person more empathetic to other peoples' mental states, say researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Brain Scans Reveal Why Meditation Works Live Science - June 30, 2007

If you name your emotions, you can tame them, according to new research that suggests why meditation works. Brain scans show that putting negative emotions into words calms the brain's emotion center. That could explain meditation’s purported emotional benefits, because people who meditate often label their negative emotions in an effort to let them go.

Meditation Gives Brain a Charge, Study Finds Washington Post - January 3, 2005

Brain research is beginning to produce concrete evidence for something that Buddhist practitioners of meditation have maintained for centuries: Mental discipline and meditative practice can change the workings of the brain and allow people to achieve different levels of awareness. Those transformed states have traditionally been understood in transcendent terms, as something outside the world of physical measurement and objective evaluation.

Areas of the brain activated during meditation - Tracing the Synapses of Spirituality

June 17, 2001 - Washington Post

In Philadelphia, a researcher discovers areas of the brain that are activated during meditation. At two other universities in San Diego and North Carolina, doctors study how epilepsy and certain hallucinogenic drugs can produce religious epiphanies. And in Canada, a neuroscientist fits people with magnetized helmets that produce "spiritual" experiences for the secular. The work is part of a broad new effort by scientists around the world to better understand religious experiences, measure them, and even reproduce them. Using powerful brain imaging technology, researchers are exploring what mystics call nirvana, and what Christians describe as a state of grace. Scientists are asking whether spirituality can be explained in terms of neural networks, neurotransmitters and brain chemistry.

What creates that transcendental feeling of being one with the universe? It could be the decreased activity in the brain's parietal lobe, which helps regulate the sense of self and physical orientation, research suggests. How does religion prompt divine feelings of love and compassion? Possibly because of changes in the frontal lobe, caused by heightened concentration during meditation. Why do many people have a profound sense that religion has changed their lives? Perhaps because spiritual practices activate the temporal lobe, which weights experiences with personal significance.

"The brain is set up in such a way as to have spiritual experiences and religious experiences," said Andrew Newberg, a Philadelphia scientist who authored the book "Why God Won't Go Away." "Unless there is a fundamental change in the brain, religion and spirituality will be here for a very long time. The brain is predisposed to having those experiences and that is why so many people believe in God."

The research may represent the bravest frontier of brain research. But depending on your religious beliefs, it may also be the last straw. For while Newberg and other scientists say they are trying to bridge the gap between science and religion, many believers are offended by the notion that God is a creation of the human brain, rather than the other way around. "It reinforces atheistic assumptions and makes religion appear useless," said Nancey Murphy, a professor of Christian philosophy at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, Calif. "If you can explain religious experience purely as a brain phenomenon, you don't need the assumption of the existence of God."

Some scientists readily say the research proves there is no such thing as God. But many others argue that they are religious themselves, and that they are simply trying to understand how our minds produce a sense of spirituality.

Newberg, who was catapulted to center stage of the neuroscience-religion debate by his book and some recent experiments he conducted at the University of Pennsylvania with co-researcher Eugene D'Aquili, says he has a sense of his own spirituality, though he declined to say whether he believed in God because any answer would prompt people to question his agenda. "I'm really not trying to use science to prove that God exists or disprove God exists," he said. Newberg's experiment consisted of taking brain scans of Tibetan Buddhist meditators as they sat immersed in contemplation. After giving them time to sink into a deep meditative trance, he injected them with a radioactive dye. Patterns of the dye's residues in the brain were later converted into images.

Newberg found that certain areas of the brain were altered during deep meditation. Predictably, these included areas in the front of the brain that are involved in concentration. But Newberg also found decreased activity in the parietal lobe, one of the parts of the brain that helps orient a person in three-dimensional space. "When people have spiritual experiences they feel they become one with the universe and lose their sense of self," he said. "We think that may be because of what is happening in that area ≠ if you block that area you lose that boundary between the self and the rest of the world. In doing so you ultimately wind up in a universal state."

Across the country, at the University of California in San Diego, other neuroscientists are studying why religious experiences seem to accompany epileptic seizures in some patients. At Duke University, psychiatrist Roy Mathew is studying hallucinogenic drugs that can produce mystical experiences and have long been used in certain religious traditions.

Could the flash of wisdom that came over Siddhartha Gautama - the Buddha - have been nothing more than his parietal lobe quieting down? Could the voices that Moses and Mohammed heard on remote mountain tops have been just a bunch of firing neurons - an illusion? Could Jesus's conversations with God have been a mental delusion?

Newberg won't go so far, but other proponents of the new brain science do. Michael Persinger, a professor of neuroscience at Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario, has been conducting experiments that fit a set of magnets to a helmet-like device. Persinger runs what amounts to a weak electromagnetic signal around the skulls of volunteers. Four in five people, he said, report a "mystical experience, the feeling that there is a sentient being or entity standing behind or near" them. Some weep, some feel God has touched them, others become frightened and talk of demons and evil spirits. "That's in the laboratory," said Persinger. "They know they are in the laboratory. Can you imagine what would happen if that happened late at night in a pew or mosque or synagogue?" His research, said Persinger, showed that "religion is a property of the brain, only the brain and has little to do with what's out there." Those who believe the new science disproves the existence of God say they are holding up a mirror to society about the destructive power of religion. They say that religious wars, fanaticism and intolerance spring from dogmatic beliefs that particular gods and faiths are unique, rather than facets of universal brain chemistry.

James Austin, a neurologist, began practicing Zen meditation during a visit to Japan. After years of practice, he found himself having to re-evaluate what his professional background had taught him. "It was decided for me by the experiences I had while meditating," said Austin, author of the book "Zen and the Brain" and now a philosophy scholar at the University of Idaho. "Some of them were quickenings, one was a major internal absorption ≠ an intense hyper-awareness, empty endless space that was blacker than black and soundless and vacant of any sense of my physical bodily self. I felt deep bliss. I realized that nothing in my training or experience had prepared me to help me understand what was going on in my brain. It was a wake-up call for a neurologist."

Austin's spirituality doesn't involve a belief in God ≠ it is more in line with practices associated with some streams of Hinduism and Buddhism. Both emphasize the importance of meditation and its power to make an individual loving and compassionate ≠ most Buddhists are disinterested in whether God exists. But theologians say such practices don't describe most people's religiousness in either eastern or western traditions.

"When these people talk of religious experience, they are talking of a meditative experience," said John Haught, a professor of theology at Georgetown University. "But religion is more than that. It involves commitments and suffering and struggle ≠ it's not all meditative bliss. It also involves moments when you feel abandoned by God." "Religion is visiting widows and orphans," he said. "It is symbolism and myth and story and much richer things. They have isolated one small aspect of religious experience and they are identifying that with the whole of religion."

Belief and faith, argue believers, are larger than the sum of their brain parts: "The brain is the hardware through which religion is experienced," said Daniel Batson, a University of Kansas psychologist who studies the effect of religion on people. "To say the brain produces religion is like saying a piano produces music." At the Fuller Theological Seminary's school of psychology, Warren Brown, a cognitive neuropsychologist, said, "Sitting where I'm sitting and dealing with experts in theology and Christian religious practice, I just look at what these people know about religiousness and think they are not very sophisticated. They are sophisticated neuroscientists, but they are not scholars in the area of what is involved in various forms of religiousness."

At the heart of the critique of the new brain research is what one theologian at St. Louis University called the "nothing-butism" of some scientists ≠ the notion that all phenomena could be understood by reducing them to basic units that could be measured. And finally, say believers, if God existed and created the universe, wouldn't it make sense that he would install machinery in our brains that would make it possible to have mystical experiences? "Neuroscientists are taking the viewpoints of physicists of the last century that everything is matter," said Mathew, the Duke psychiatrist. "I am open to the possibility that there is more to this than what meets the eye. I don't believe in the omnipotence of science or that we have a foolproof explanation."