Building Blog Architectural Journal - January 9, 2009

In a surprisingly under-reported story from 2007, Mark Holley, a professor of underwater archaeology at Northwestern Michigan University College, discovered a series of stones Ð some of them arranged in a circle and one of which seemed to show carvings of a mastodon - 40-feet beneath the surface waters of Lake Michigan. If verified, the carvings could be as much as 10,000 years old - coincident with the post-Ice Age presence of both humans and mastodons in the upper midwest.

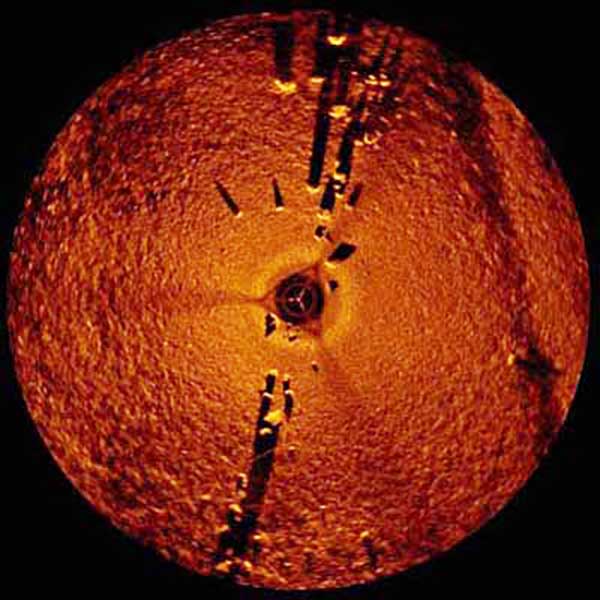

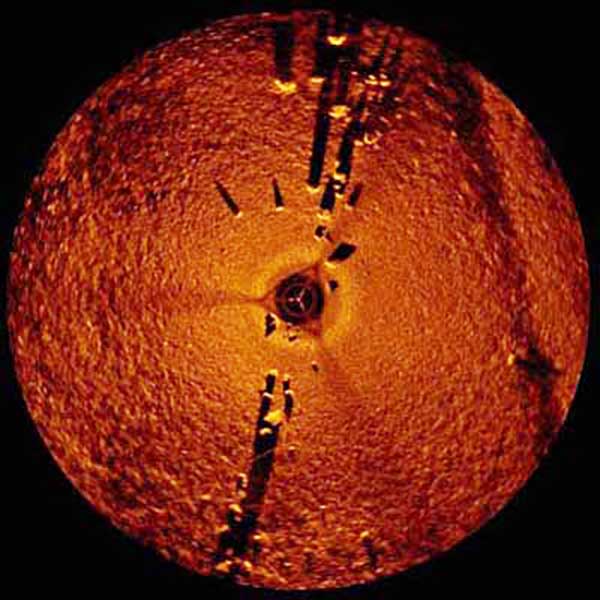

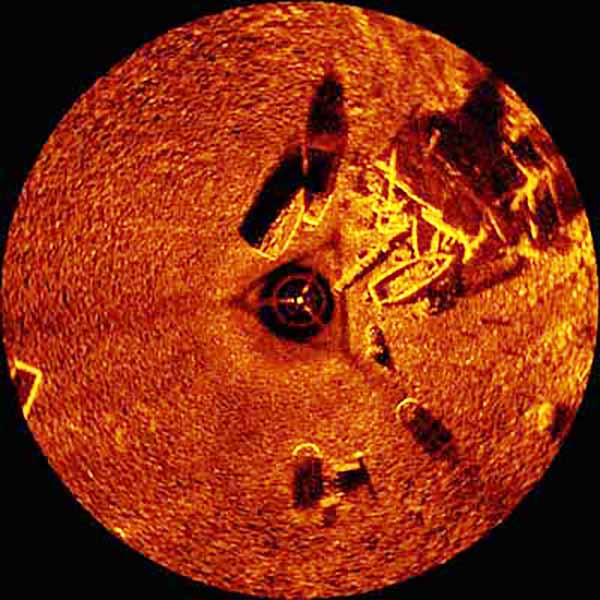

In a PDF assembled by Holley and Brian Abbott to document the expedition, we learn that the archaeologists had been hired to survey a series of old boat wrecks using a slightly repurposed "sector scan sonar" device. You can read about the actual equipment - a Kongsberg-Mesotech MS 1000 - here.

The circular images this thing produces are unreal; like some strange new art-historical branch of landscape representation, they form cryptic dioramas of long-lost wreckage on the lakebed. Shipwrecks (like the Tramp, which went down in 1974); a "junk pile" of old boats and cars; a Civil War-era pier; and even an old buggy are just some of the topographic features the divers discovered.

These are anthropological remains that will soon be part of the lake's geology; they are our future trace fossils. But down amongst those otherwise mundane human remains were the stones.

While there is obviously some doubt as to whether or not that really is a mastodon carved on a rock Ð let alone if it really was human activity that arranged some of the rocks into a Stonehenge-like circle Ð it's worth pointing out that Michigan does already have petroglyph sites and even standing stones.

A representative of the University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology has even commented that, although he's skeptical, he's interested in learning more, hoping to see better photographs of the so-called "glyph stone."

So is there a North American version of Stonehenge just sitting up there beneath the glacial waters of a small northern bay in Lake Michigan? If so, are there other submerged prehistoric megaliths waiting to be discovered by some rogue archaeologist armed with a sonar scanner? Whatever the answer might be, the very suggestion is interesting enough to think about - where underwater archaeology, prehistoric remains, and lost shipwrecks collide to form a midwestern mystery