The images of the top two skulls were photographed by Robert Connolly on his trip around the world during which he was collecting materials about ancient civilizations. The discovery of unusual skulls was thus an unintended "spinoff" of his efforts.

The data about the skulls is incomplete, and that makes the correct assessment of their age, context with other hominids, as well as placement of their origin extremely difficult. Some of the skulls are very distinct, as if they belong to entirely different species, remotely similar to genus Homo. The first thing that attracts attention is the size and shape of the cranium in all the specimens. There are 4 different groups represented in the pictures. As a matter of convenience, I labeled them "conehead", "jack-o-lantern" or "J" and "M" based on the shape of the skull, except the first and possibly earliest type of skull, which I call "premodern".

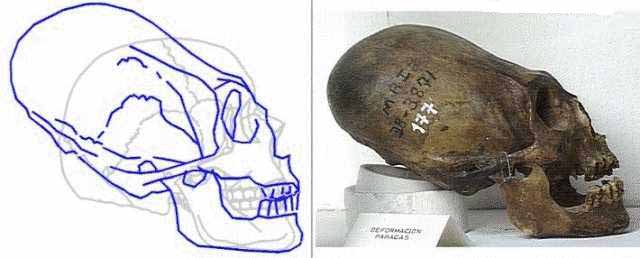

When some of these pictures (the first two) were posted on CompuServe more than year ago, the majority of people assumed that they represented an example of binding of the head, well known to be in fashion in ancient Nubia, Egypt and other cultures. The problem with this theory is that the inside of the cranium of the mentioned skulls, although elongated and with a back sloping, flattened forehead, have the same capacity as normal human skulls; the only difference is the shape achieved by frontal and side deformations. They are actually more similar to the first type of skull (premodern) with the rounded back, than the cone-head type. The cone-shaped types of skull are not found amongst the usual skull-binding samples.

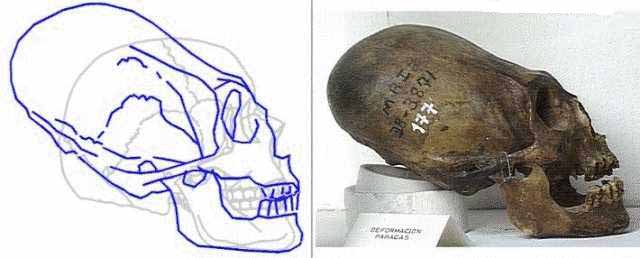

The first skull presents problems of its own. The frontal part of the skull seems to belong to an individual of the pre-Neanderthal family, but the lower jaw, though more robust than modern human type, has a modern shape and characteristics. The shape of the cranium does not have any comparison with the Erectus, Neanderthal types, nor the modern human type. Some minor Neanderthal characteristics are present, as is the occipital ridge on the bottom back of the skull and the flattened bottom of the cranium, other characteristics point more towards Homo Erectus. The angle of the cranial bottom is, though, unusual. We cannot exclude the possibility of a deformed individual in this case, but it is highly unlikely that the angle of the frontal part would require a modification of the lower jaw in the process of growing to resemble modern human types with their projected chin rim. The answer seems to be that the skull belongs to a representative of an unknown premodern human or humanoid type.

As is obvious from the comparison with a modern human skull, the cranial capacity lies within the modern human range. This is not surprising, since the late Neanderthals and early modern humans (Cro-Magnon) had larger cranial capacities (both roughly 1600 ccm to 1750 ccm) than modern humans (av. 1450 ccm). The decrease of the cranial capacity (sudden at that -- the specimens of modern humans after about 10500 BCE have smaller craniums) is a puzzling matter, but that's another story.

No less puzzling is what a representative of a premodern human type is doing on the South American continent. According to the orthodox anthropology, this skull simply does not exist, because it cannot be. Textbooks' oldest date of appearance of humans in North America is about 35000 BCE and much later for South America, based on the diffusion theory assumptions. The only accepted human types entering the continent are of the modern anatomy. There are some other sources that place all types of human genus in both Americas at much earlier dates based on numerous anomalous finds, but the academe sticks to its preconceived notions, no matter what. It's safer

The "premodern" skull and the following three specimens were found in the Paracas region of Perœ. It does not necessarily mean that they are related. There is some possibility that the "premodern" is in fact a precursor of the "conehead" type, but since we do not have any dating analysis at hand, we may only speculate in this regard.

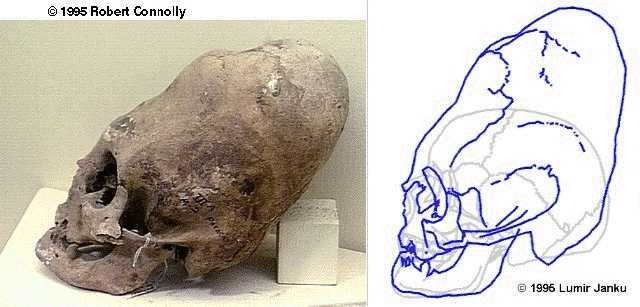

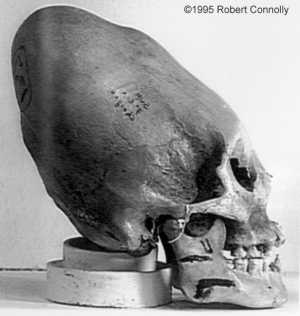

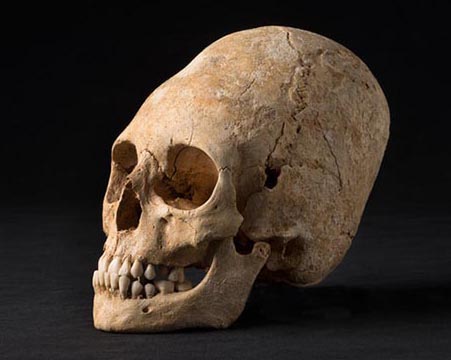

The "conehead" type is very unusual because of the cranial shape. Here we have three specimens, which exclude the possibility of random or artificial deformation (the already mentioned Nubian deformations had quite a number of individual variations). They have individual characteristics within the range of overall morphology. There is no doubt that they are closely related and possibly represent quite a distinct branch of the genus Homo, if not an entirely different species.

The comparison of the C1 with a modern human skull has slight inaccuracies, caused by a degree of distortion when rotating the skull shape into position. As is obvious from C2 and C3, the angle of the bottom part of the cranium does not deviate from normal. However, the general proportions are correct.

The enormity of the cranial vault is obvious from all three pictures. By interpolation, we can estimate the minimum cranial capacity at 2200 ccm, but the value can be as high as 2500 ccm. The shape of the skull may be a biological response--a survival of the species mechanism--to increase the brain mass without the danger of relegating the species to extinction and keeping a viable biological reproduction intact. However, since we do not see the representatives of the "conehead" type in modern population, something prevented the type becoming as widespread as it is in the case of present-day moderns.

The "J" type of skull presents different sets of problems. It is an equivalent of the modern type of skull in all respects, with only several factors out of proportion. Less significant is the size of eye sockets which are about 15% larger than in modern populations. More significant is the enormity of the cranial vault. The estimated cranial capacity ranges between minimum of 2600 ccm to 3200 ccm.

New insights into the origin of elongated heads in early medieval Germany Science Daily - March 13, 2018

A palaeogenomic study investigates early medieval migration in southern Germany and the peculiar phenomenon of artificial skull deformation. In an interdisciplinary study, the international research team analyzed the ancient genomes of almost 40 early medieval people from southern Germany. While most of the ancient Bavarians looked genetically like Central and Northern Europeans, one group of individuals had a very different and diverse genetic profile. Members of this group were particularly notable in that they were women whose skulls had been artificially deformed at birth. Such enigmatic deformations give the skull a characteristic tower shape and have been found in past populations from across the world and from different periods of time.

Parents wrapped their children's heads with bandages for a few months after birth in order to achieve the desired head shape. It is difficult to answer why they carried out this elaborate process, but it was probably used to emulate a certain ideal of beauty or perhaps to indicate a group affiliation. So far, scholars have only speculated about origins of the practice in medieval Europe. The presence of these elongated skulls in parts of eastern Europe is most commonly attributed to the nomadic Huns, led by Atilla, during their invasion of the Roman Empire from Asia, but the appearance of these skulls in western Europe is more mysterious, as this was very much the fringes of their territory.

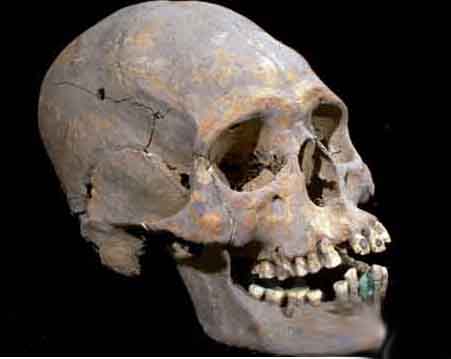

Skeleton With Alien-Like Skull Found Discovery - July 11, 2016

The specimen, found in Mexico, also had stone-encrusted teeth. Archaeologists in Mexico have unearthed the 1,600 year old skeleton of a woman with an elongated, "alien-like" skull and stone-encrusted teeth. Found at a town called San Juan Evangelista, near the ancient ruins of Teotihuacan some 30 miles from Mexico City, the skeleton belongs to an upper class woman who died at around 35-40 years of age. They estimate the burial dates between 350-400 AD.

'

Deformed, Pointy Skull from Dark Ages Unearthed in France Live Science - November 15, 2013

The skeleton of an ancient aristocratic woman whose head was warped into a deformed, pointy shape has been unearthed in a necropolis in France. The necropolis, found in the Alsace region of France, contains 38 tombs that span more than 4,000 years, from the Stone Age to the Dark Ages. The Obernai region where the remains were found contains a river and rich, fertile soil, which has attracted people for thousands of years.