This dynasty traced its origins to 24th dynasty. Psamtik I was probably a descendant of Bakenrenef, and following the Assyrians' invasions during the reigns of Taharqa and Tantamani, he was recognized as sole king over all of Egypt. While the Assyrian Empire was preoccupied with revolts and civil war over control of the throne, Psammetichus threw off his ties to the Assyrians, and formed alliances with Gyges, king of Lydia, and recruited mercenaries from Caria and Greece to resist Assyrian attacks.

With the sack of Nineveh in 612 BC and the fall of the Assyrian Empire, both Psamtik and his successors attempted to reassert Egyptian power in the Near East, but were driven back by the Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar II. With the help of Greek mercenaries, Apries was able to hold back Babylonian attempts to conquer Egypt, but it was the Persians who conquered Egypt, and their king Cambyses II carried Psamtik III to Susa in chains.

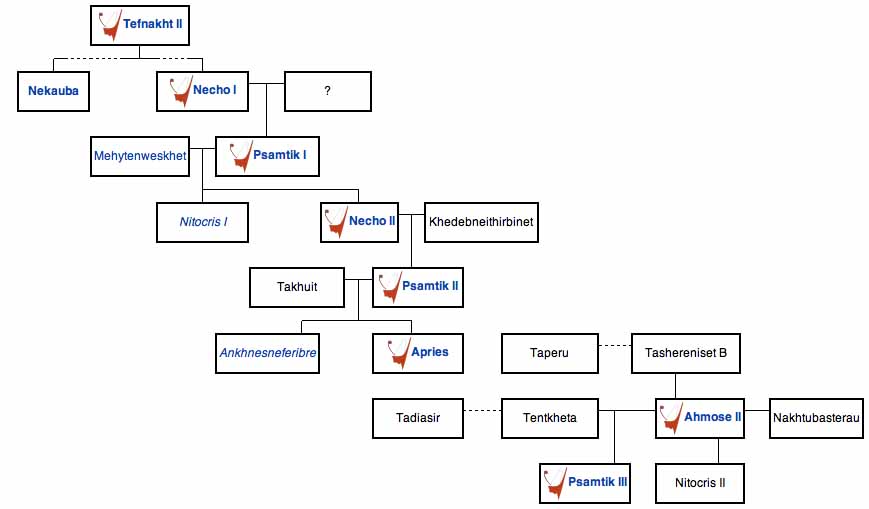

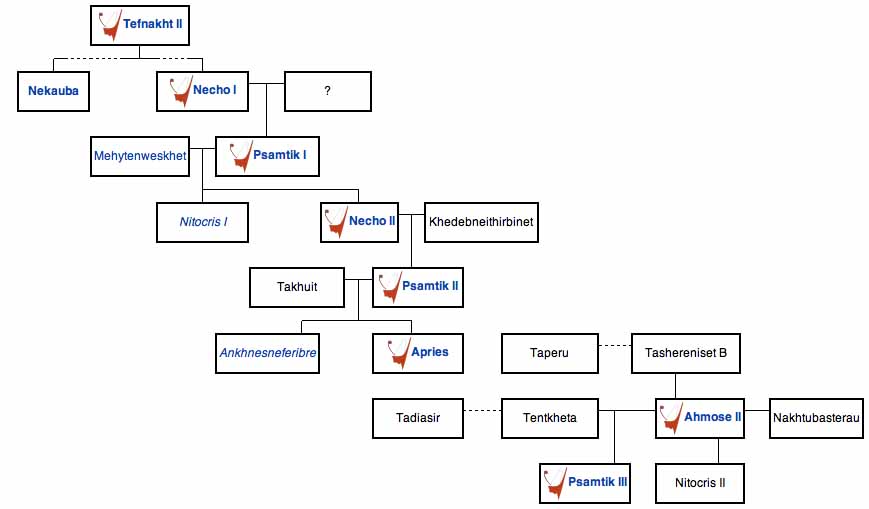

The 26th dynasty may be related to the 24th dynasty. Manetho begins the dynasty with:

Sextus Julius Africanus states in his often accurate version of Manetho's Epitome that the dynasty numbered 9 pharaohs, beginning with a "Stephinates" (Tefnakht II) and ending with Psamtik III. Africanus also notes that Psamtik I and Necho I ruled for 54 and 8 years respectively.

Psamtik I (also spelled Psammeticus or Psammetichus, was the first of three kings of that name of the Saite, or Twenty-sixth dynasty of Egypt. His prenomen, Wah-Ib-Re, means "Constant is the Heart of Re."

The story in Herodotus of the Dodecarchy and the rise of Psamtik is fanciful. It is known from cuneiform texts that twenty local princelings were appointed by Esarhaddon and confirmed by Assurbanipal to govern Egypt. Necho I, the father of Psammetichus by his Queen Istemabet, was the chief of these kinglets, but they seem to have been quite unable to hold the Egyptians to the hated Assyrians against the more sympathetic Nubians.

The labyrinth built by Amenemhat III of the Twelfth dynasty of Egypt is ascribed by Herodotus to the Dodecarchy, or rule of 12, which must represent this combination of rulers. Psamtik was the son of Necho I who died in 664 BC when the Kushite king Tantamani tried unsuccessfully to seize control of lower Egypt from the Assyrian Empire. After his father's death, Psamtik managed to both unite all of Egypt and free her from Assyrian control within.

The Greek historian Herodotus conveyed an anecdote about Psamtik in the second volume of his Histories (2.2). During his travel to Egypt, Herodotus heard that Psammetichus ("Psamtik") sought to discover the origin of language by conducting an experiment with two children. Allegedly he gave two newborn babies to a shepherd, with the instructions that no one should speak to them, but that the shepherd should feed and care for them while listening to determine their first words.

The hypothesis was that the first word would be uttered in the root language of all people. When one of the children cried "bekos" with outstretched arms the shepherd concluded that the word was Phrygian because that was the sound of the Phrygian word for "bread." Thus, they concluded that the Phrygians were an older people than the Egyptians, and that Phrygian was the original language of men. There are no other extant sources to verify this story.

Psamtik's chief wife was Mehtenweskhet, the daughter of Harsiese, the Vizier of the North and High Priests of Atum at Heliopolis. Psamtik and Mehtenweshket were the parents of Necho II, Merneith, and the Divine Adoratice Nitocris I.

Psamtik's father-in-law - the aforementioned Harsiese - was married three times: to Sheta, with whom he had a daughter named Naneferheres, to Tanini and, finally, to an unknown lady, by whom he had both Djedkare, the Vizier of the South and Mehtenweskhet. Harsiese was the son of Vizier Harkhebi, and was related to two other Harsieses, both Viziers, who were a part of the family of the famous Mayor of Thebes Montuemhat.

Necho II (sometimes Nekau) was a king of the twenty-sixth dynasty of Egypt (610 BC - 595 BC). He is most likely the pharaoh mentioned in several books of the Bible (see Hebrew Bible / Old Testament). The Book of Kings states that Necho met King Josiah of the Kingdom of Judah at Megiddo and killed him (2 Kings 23:29).

The Book of Chronicles 2 Chronicles 35:20-27 gives a lengthier account and 2 Chronicles 35:20 states that when Josiah had prepared the temple, Necho king of Egypt came up to fight against the Babylonians at Carchemish on the Euphrates River and that King Josiah was fatally wounded by an Egyptian archer. He was then brought back to Jerusalem to die.

According to the Book of Jeremiah in the summer of 605 BC Carchemish was the site of an important battle was fought by the Babylonian army of Nebuchadrezzar II and that of Pharaoh Necho II of Egypt. The aim of Necho's campaign was to contain the Westward advance of the Babylonian Empire and cut off its trade route across the Euphrates. However, the Egyptians were defeated by the unexpected attack of the Babylonians and were eventually expelled from Syria.

The Egyptologist Donald B. Redford observed that although Necho II was "a man of action from the start, and endowed with an imagination perhaps beyond that of his contemporaries, Necho had the misfortune to foster the impression of being a failure.

Necho II was the son of Psammetichus I by his Great Royal Wife Mehtenweskhet. His prenomen or royal name Wahem-Ib-Re means "Carrying out the Heart (ie. Wish) of Re.

Necho played a significant role in the histories of the Assyrian Empire, Babylonia and the Kingdom of Judah. Upon his ascension, Necho was faced with the chaos created by the raids of the Cimmerians and the Scythians, who had not only ravaged Asia west of the Euphrates, but had also helped the Babylonians shatter the Assyrian Empire. That once mighty empire was now reduced to the troops, officials, and nobles who had gathered around a general holding out at Harran, who had taken the throne name of Ashur-uballit II. Necho attempted to assist this remnant immediately upon his coronation, but the force he sent proved to be too small, and the combined armies were forced to retreat west across the Euphrates.

In the spring of 609 BC, Necho personally led a sizable force to help the Assyrians. At the head of a large army, consisting mainly of his mercenaries, Necho took the coast route Via Maris into Syria, supported by his Mediterranean fleet along the shore, and proceeded through the low tracts of Philistia and Sharon. He prepared to cross the ridge of hills which shuts in on the south the great Jezreel Valley, but here he found his passage blocked by the Judean army. Their king, Josiah, sided with the Babylonians and attempted to block his advance at Megiddo, where a fierce battle was fought and Josiah was killed (2 Kings 23:29, 2 Chronicles 35:20-24).

Necho soon captured Kadesh on the Orontes and moved forward, joining forces with Ashur-uballit and together they crossed the Euphrates and laid siege to Harran. Although Necho became the first pharaoh to cross the Euphrates since Thutmose III, he failed to capture Harran, and retreated back to northern Syria. At this point, Ashur-uballit vanished from history, and the Assyrian Empire was conquered by the Babylonians.

Leaving a sizable force behind, Necho returned to Egypt. On his return march, he found that the Judeans had selected Jehoahaz to succeed his father Josiah, whom Necho deposed and replaced with Jehoiakim. He brought Jehoahaz back to Egypt as his prisoner, where Jehoahaz ended his days (2 Kings 23:31; 2 Chronicles 36:1-4).

Meanwhile, the Babylonian king was planning on reasserting his power in Syria. In 609 BC, King Nabopolassar captured Kumukh, which cut off the Egyptian army, then based at Carchemish. Necho responded the following year by retaking Kumukh after a four month siege, and executed the Babylonian garrison. Nabopolassar gathered another army, which camped at Qurumati on the Euphrates. However, Nabopolassar's poor health forced him to return to Babylon in 605 BC. In response, in 606 BC the Egyptians attacked the leaderless Babylonians (probably then led by the crown prince Nebuchadrezzar) who fled their position.

At this point, the aged Nabopolassar, passed command of the army to his son Nebuchadrezzar II, who led them to a decisive victory over the Egyptians at Carchemish, and pursued the fleeing survivors to Hamath. Necho's dream of restoring the Egyptian Empire in the Middle East as had occurred under the New Kingdom was destroyed as Nebuchadrezzar conquered Egyptian territory from the Euphrates to the Brook of Egypt (Jeremiah 46:2; 2 Kings 23:29) down to Judea.

Although Nebuchadrezzar spent many years in his new conquests on continuous pacification campaigns, Necho was unable to recover any significant part of his lost territories. For example, when Ashkalon rose in revolt, despite repeated pleas the Egyptians sent no help, and were barely able to repel a Babylonian attack on their eastern border in 601 BC. When he did repel the Babylonian attack, Necho managed to capture Gaza while pursuing the enemy. Necho turned his attention in his remaining years to forging relationships with new allies: the Carians, and further to the west, the Greeks.

At some point during his Syrian campaign, Necho II initiated but never completed the ambitious project of cutting a navigable canal from the Pelusiac branch of the Nile to the Red Sea. Necho's Canal was the earliest precursor of the Suez Canal. It was in connection with this new activity that Necho founded a new city of Per-Temu Tjeku which translates as 'The House of Atum of Tjeku' at the site now known as Tell el-Maskhuta, about 15 km west of Ismailia. The waterway was intended to facilitate trade between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean. Necho also formed an Egyptian navy by recruiting displaced Ionian Greeks. This was an unprecedented act by the pharaoh since most Egyptians had traditionally harboured an inherent distaste for and fear of the sea. The navy which Necho created operated along both the Mediterranean and Red Sea coasts.

Herodotus (4.42) also reports that Necho sent out an expedition of Phoenicians, who in three years sailed from the Red Sea around Africa back to the mouth of the Nile. Some current historians tend to believe Herodotus' account, primarily because he stated with disbelief that the Phoenicians " as they sailed on a westerly course round the southern end of Libya (Africa), they had the sun on their right - to northward of them" (The Histories 4.42) -- in Herodotus' time it was not known that Africa extended south past the equator; however, Egyptologists also point out that it would have been extremely unusual for an Egyptian Pharaoh to carry out such an expedition. Alan B. Lloyd doubts the event and attributes the development of the story by other events.

Necho II died in 595 BC and was succeeded by his son, Psamtik II, as the next pharaoh of Egypt. Psamtik II, however, later removed Necho's name from almost all of his father's monuments for unknown reasons.

Apries is the name by which Herodotus (ii. 161) and Diodorus (i. 68) designate Wahibre Haaibre, (Pharaoh-Hophra), a pharaoh of Egypt (589 BC - 570 BC), the fourth king (counting from Psamtik I) of the Twenty-sixth dynasty of Egypt. He was equated with the Waphres of Manetho, who correctly records that he reigned for 19 years. Apries is also called Hophra in Jeremiah 44:30.

Apries inherited the throne from his father, pharaoh Psamtik II, in February 589 BC and his reign continued his father's history of foreign intrigue in Palestinian affairs. Apries was an active builder who constructed "additions to the temples at Athribis (Tell Atrib), Bahariya Oasis, Memphis and Sais."

In Year 4 of his reign, Apries' sister Ankhnesneferibre was adopted as the new God's Wife of Amun at Thebes. However, Apries' reign was also fraught with internal problems. In 588 BC, Apries dispatched a force to Jerusalem to protect it from Babylonian forces sent by Nebuchadrezzar II. His forces were quickly crushed and Jerusalem was destroyed by the Babylonians. His unsuccessful attempt to intervene in the politics of the Kingdom of Judah was followed by a mutiny of soldiers from the strategically important Aswan garrison.

While the mutiny was contained, Apries later attempted to protect Libya from incursions by Dorian Greek invaders but his efforts here backfired spectacularly as his forces were mauled by the Greek invaders. When the defeated army returned home, a civil war broke out between the indigenous Egyptian army troops and foreign mercenaries in the Egyptian army.

At this time of crisis, the Egyptians turned in support towards a victorious general, Amasis II who had led Egyptian forces in a highly successful invasion of Nubia in 592 BC under pharaoh Psamtik II, Apries' father. Amasis quickly declared himself pharaoh in 570 BC and Apries fled Egypt and sought refuge in another foreign country. When Apries marched back to Egypt in 567 BC with the aid of a Babylonian army to reclaim the throne of Egypt, he was likely killed in battle with Amasis' forces. Amasis thus secured his kingship over Egypt and was now the unchallenged ruler of Egypt.

Amasis, however, reportedly treated Apries' mortal remains with respect and observed the proper funerary rituals by having Apries' body carried to Sais and buried there with "full military honours." Amasis, the former general who had declared himself pharaoh also married Apries' daughter Chedebnitjerbone II to legitimise his accession to power. While Herodotus claimed that the wife of Apries was called Nitetis in (Greek), "there are no contemporary references naming her" in Egyptian records.Eusebius placed the eclipse of Thales in 585 BC in the eighth or twelfth year of Apries' reign.

An obelisk which Apries erected at Sais was moved by the 3rd century AD Roman Emperor Diocletian and originally placed at the Temple of Isis in Rome. It is today located in front of the Santa Maria sopra Minerva basilica church in Rome.

Amasis II or Ahmose II was a pharaoh (570 B.C.E. - 526 B.C.E.) of the Twenty-sixth dynasty of Egypt, the successor of Apries at Sais. He was the last great ruler of Egypt before the Persian conquest.

Most of our information about him is derived from Herodotus (2.161ff) and can only be imperfectly verified by monumental evidence. According to the Greek historian, he was of common origins A revolt which broke out among native Egyptian soldiers gave him his opportunity to seize the throne. These troops, returning home from a disastrous military expedition to Cyrene in Libya, suspected that they had been betrayed in order that Apries, the reigning king, might rule more absolutely by means of his Greek mercenaries; many Egyptians fully sympathized with them.

Relief of Amasis at Karnak Temple

General Amasis, sent to meet them and quell the revolt, was proclaimed king by the rebels instead, and Apries, who had now to rely entirely on his mercenaries, was defeated. Apries was either taken prisoner in the ensuing conflict at Memphis before being eventually strangled and buried in his ancestral tomb at Sais, or fled to the Babylonians and was killed mounting an invasion of his native homeland in 567 B.C.E. with the aid of a Babylonian army. An inscription confirms the struggle between the native Egyptian and the foreign soldiery, and proves that Apries was killed and honourably buried in the third year of Amasis (c.567 B.C.E.). Amasis then married Chedebnitjerbone II, one of the daughters of his predecessor Apries, in order to legitimize his kingship.

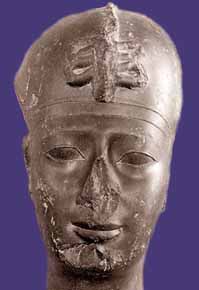

Some information is known about the family origins of Amasis: his mother was a certain Tashereniset as a bust statue of this lady, which is today located in the British Museum, shows. A stone block from Mehallet el-Kubra also establishes that his maternal grandmother - Tashereniset's mother - was a certain Tjenmutetj

Herodotus describes how Amasis II would eventually cause a confrontation with the Persian armies. According to Herodotus, Amasis, was asked by Cambyses II or Cyrus the Great for an Egyptian ophthalmologist on good terms. Amasis seems to have complied by forcing an Egyptian physician into mandatory labor causing him to leave his family behind in Egypt and move to Persia in forced exile. In an attempt to exact revenge for his forced exile, the physician would grow very close with Cambyses and would suggest that Cambyses should ask Amasis for a daughter in marriage in order to solidify his bonds with the Egyptians. Cambyses complied and requested a daughter of Amasis for marriage.

Amasis worrying that his daughter would be a concubine to the Persian king refused to give up his offspring; Amasis also was not willing to take on the Persian empire so he concocted a trickery in which he forced the daughter of the ex-pharaoh Apries, whom Herodotus explicitly confirms to have been killed by Amasis, to go to Persia instead of his own offspring.

This daughter of Apries, was none other than Nitetis, who was as per Herodotus's account, "tall and beautiful." Nitetis naturally, betrayed Amasis and upon being greeted by the Persian king explained Amasis' trickery and her true origins. This infuriated Cambyses and he vowed to take revenge for it. Amasis would die before Cambyses reached him, but his heir and son Psamtik III would be defeated by the Persians.

Herodotus also describes that just like his predecessor, Amasis II relied on Greek mercenaries and council men. One such figure was Phanes of Halicarnassus, who would later on leave Amasis, for reasons Herodotus does not clearly know but suspects were personal between the two figures. Amasis would send one of his eunuchs to capture Phanes, but the eunuch is bested by the wise council man and Phanes flees to Persia, meeting up with Cambyses providing advice in his invasion of Egypt. Egypt would finally be lost to Persians during the battle of Pelusium.

Although Amasis thus appears first as champion of the disparaged native, he had the good sense to cultivate the friendship of the Greek world, and brought Egypt into closer touch with it than ever before. Herodotus relates that under his prudent administration, Egypt reached a new level of wealth; Amasis adorned the temples of Lower Egypt especially with splendid monolithic shrines and other monuments (his activity here is proved by existing remains). Amasis assigned the commercial colony of Naucratis on the Canopic branch of the Nile to the Greeks, and when the temple of Delphi was burnt, he contributed 1,000 talents to the rebuilding. He also married a Greek princess named Ladice daughter of King Battus III and made alliances with Polycrates of Samos and Croesus of Lydia.

His kingdom consisted probably of Egypt only, as far as the First Cataract, but to this he added Cyprus, and his influence was great in Cyrene. In his fourth year (c.567 B.C.E.), Amasis was able to defeat an invasion of Egypt by the Babylonians under Nebuchadrezzar II; henceforth, the Babylonians experienced sufficient difficulties controlling their empire that they were forced to abandon future attacks against Amasis.

However, Amasis was later faced with a more formidable enemy with the rise of Persia under Cyrus who ascended to the throne in 559 B.C.E.; his final years were preoccupied by the threat of the impending Persian onslaught against Egypt.

With great strategic skill, Cyrus had destroyed Lydia in 546 B.C.E. and finally defeated the Babylonians in 538 B.C.E. which left Amasis with no major Near Eastern allies to counter Persia's increasing military might. Amasis reacted by cultivating closer ties with the Greek states to counter the future Persian invasion into Egypt but was fortunate to have died in 526 B.C.E. shortly before the Persians attacked. The final assault instead fell upon his son Psamtik III, whom the Persians defeated in 525 B.C.E. after a reign of only six months.

Amasis II died in 526 BC. He was buried at the royal necropolis of Sais, and while his tomb was never discovered, Herodotus describes it for us:

Relief depicting Psamtik III from a chapel in Karnak

Psamtik III (also spelled Psammetichus or Psammeticus) was the last Pharaoh of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt from 526 BC to 525 BC. Most of what is known about his reign and life was documented by the Greek historian Herodotus in the 5th century. Herodotus states that Psamtik had ruled Egypt for only six months before he was confronted by a Persian invasion of his country led by King Cambyses II of Persia. Psammetichus was subsequently defeated at Pelusium, and fled to Memphis where he was captured. The deposed pharaoh was carried off to Susa in chains, and later executed.

Psamtik III was the son of the pharaoh Amasis II and one of his wives, Queen Tentkheta. He succeeded his father as pharaoh in 526 BC, when Amasis died after a long and prosperous reign of some 44 years. According to Herodotus, he had a son named Amasis and a wife and daughter, both unnamed in historical documents.

Psamtik ruled Egypt for no more than six months. A few days after his coronation, rain fell at Thebes, which was a rare event that frightened some Egyptians, who interpreted this as a bad omen. The young and inexperienced pharaoh was no match for the invading Persians. After the Persians under Cambyses had crossed the Sinai desert with the aid of the Arabs, a bitter battle was fought near Pelusium, a city on Egypt's eastern frontier, in the spring of 525 BC.

The Egyptians were defeated at Pelusium and Psamtik was betrayed by one of his allies, Phanes of Halicarnas. Consequently, Psamtik and his army were compelled to withdraw to Memphis. The Persians captured the city after a long siege, and captured Psamtik after its fall. Shortly thereafter, Cambyses ordered the public execution of two thousand of the principal citizens, including (it is said) a son of the fallen king.

According to book III of The History by Herodotus, Psamtik's daughter was enslaved, his son given a death sentence, and a male companion was turned into a beggar. They were all brought before him to test his reaction, and he only became upset over seeing the state of the beggar. Psamtik III was spared but his son was cut to pieces. The deposed pharaoh was imprisoned and taken to Susa in chains where he was initially treated relatively well. After a while, however, Psamtik reportedly plotted a rebellion against Cambyses and was executed for his involvement in this conspiracy by being forced to drink bull's blood thereby causing his death.