The history of Achaemenid Egypt is divided into two eras: an initial period of Achaemenid Persian occupation when Egypt became a satrapy, followed by an interval of independence; and a second period of occupation, again under the Achaemenids.

The last pharaoh of the Twenty-Sixth dynasty, Psamtik III, was defeated by Cambyses II of Persia in the battle of Pelusium in the eastern Nile delta in 525 BC. Egypt was then joined with Cyprus and Phoenicia in the sixth satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire. Thus began the first period of Persian rule over Egypt (also known as the 27th Dynasty), which ended around 402 BC.

After an interval of independence, during which three indigenous dynasties reigned (the 28th, 29th, and 30th dynasty), Artaxerxes III (358-338 BC) reconquered the Nile valley for a brief second period (343-332 BC), which is called the thirty-first dynasty of Egypt.

Cambyses led three unsuccessful military campaigns in Africa: against Carthage, the Siwa Oasis, and Nubia. He remained in Egypt until 522 BC and died on the way back to Persia. The Greek and Jewish sources, especially Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus, present us a bleak portrait of Cambyses' rule, describing the king as mad, ungodly, and cruel. It is impossible unfortunately to compare these texts with Egyptian sources, as all unofficial documents appear doing their best to ignore Cambyses' existence.

Herodotus may have drawn on an indigenous tradition that reflected the Egyptians' resentment, especially of the clergy, of Cambyses' decree (known from a Demotic text on the back of papyrus no. 215 in the Bibliotheaque Nationale, Paris) curtailing royal grants made to Egyptian temples under Ahmose II.

In order to regain the support of the powerful priestly class, Darius I (522-486 BC) revoked Cambyses' decree. Diodorus reported that Darius was the sixth and last lawmaker for Egypt; according to Demotic papyrus no. 215, in the third year of his reign he ordered his satrap in Egypt, Aryandes, to bring together wise men among the soldiers, priests, and scribes, in order to codify the legal system that had been in use until the year 44 of Ahmose II (c. 526 BC).

The laws were to be transcribed on papyrus in both Demotic and Aramaic, so that the satraps and their officials, mainly Persians and Babylonians, would have a legal guide in both the official language of the empire and the language of local administration. To facilitate commerce, Darius built a navigable waterway from the Nile to the Red Sea (from Bubastis [modern Zaqaziq] through the Wadi Timelat and the Bitter Lakes); it was marked along the way by four great bilingual stelae, the so-called "canal stelae," inscribed in both hieroglyphics and cuneiform scripts.

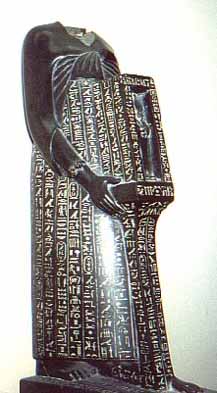

In 1972 archaeological excavations at Susa brought to light a stone statue of Darius I, standing and wearing a sumptuous Persian garment; it is inscribed in cuneiform (in Old Persian, Elamite, and Akkadian) and in hieroglyphics. This can be interpreted as a recognition of the role of Egypt in the Empire.

Shortly before 486 BC, the year of Darius' death, there was a revolt of the type that had occurred under Aryandes, that was definitively subdued by Xerxes I (486-464 BC) only in 484 BC. The province was subjected to harsh punishment for the revolt, and especially its satrap Achaemenes administered the country without regard for the opinion of his subjects.

A still more serious and extensive revolt took place in about 460 BC under Artaxerxes I. It was led by the Libyan Inaros, son of Psamtik III (Thucydides 1.104), who asked for help from Athens; a fleet of 200 ships sailed up the Nile as far as the ancient citadel of Memphis, two thirds of which was occupied by the insurgents. Achaemenes was killed in the course of the battle of Papremis in the western Delta.

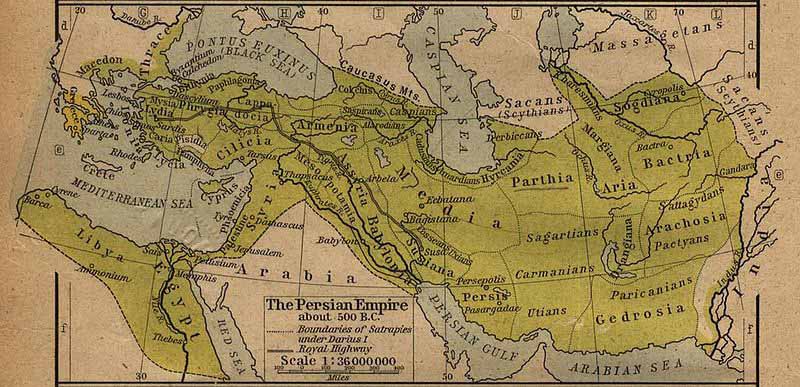

The Achaemenid empire at its greatest extent, around 500 BC.

It is not known who served as satrap after Artaxerxes III, but under Darius III (336-330 BC) there was Sabaces, who fought and died at Issus and was succeeded by Mazaces. Egyptians also fought at Issus, for example, the nobleman Somtutefnekhet of Heracleopolis, who described on the "Naples stele" how he escaped during the battle against the Greeks and how Arsaphes, the god of his city, protected him and allowed him to return home.

In 332 BC Mazaces handed over the country to Alexander the Great without a fight. The Achaemenid empire had ended, and for a while Egypt was a satrapy in Alexander's empire. Later the Ptolemies and the Romans successively ruled the Nile valley.

The Twenty-seventh Dynasty of Egypt also known as the First Egyptian Satrapy was effectively a province of the Achaemenid Persian Empire between 525 BCE to 402 BCE. The last pharaoh of the Twenty-Sixth dynasty, Psamtik III, was defeated by Cambyses II of Persia in the battle of Pelusium in the eastern Nile delta in 525 BC. Egypt was then joined with Cyprus and Phoenicia in the sixth satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire. Thus began the first period of Persian rule over Egypt (also known as the 27th Dynasty), which ended around 402 BC.

After an interval of independence, during which three indigenous dynasties reigned (the 28th, 29th, and 30th dynasty), Artaxerxes III (358-338 BC) reconquered the Nile valley for a brief second period (343-332 BC), which is called the thirty-first dynasty of Egypt.

Cambyses was the first ruler of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty. He was the ruler of Persia and treated the last ruler of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, Psammetichus III (Psamtik III) with some consideration. Psammetichus then tried to revolt and Cambyses caused him to be killed. There is an inscription on a statue that tells of Cambyses going to Sais to worship Neith and restore the revenues and festivals of the temple. But according to Herodotus, Cambyses did many reprehensible things against Egyptian religion and customs and eventually went mad.

In 525 BC the Persian emperor Cambyses II, son of Cyrus the Great, who had already named his son as king of Babylon though Cambyses II resigned that position after only one year, invaded Egypt and successfully overthrew the native Egyptian pharaoh, Psamtek III, last ruler of Egypt's 26th Dynasty to become the first ruler of Egypt's 27th Persian Dynasty. His father had earlier attempted an invasion of Egypt against Psamtek III's predecessor, Amasis, but Cyrus' death in 529 BC put a halt to that expedition.ΚΚ

The empire of Cyrus passed to his son Cambyses (530-522 BC), who was as savage and ugly of temper as Cyrus had been mild and generous. The father had conquered Asia, the son undertook the conquest of Africa. Having skillfully and successfully led his army across the deserts which separate the two continents, Cambyses met and defeated the Egyptians in front of their city at Pelusium in 525 BC just a few weeks after the death of Pharaoh Amasis of the 19th/26th Dynasty when Psammetichus II was king.

Cambyses captured Pelusium by using a clever strategy. The Egyptians regarded certain animals, especially cats, as being sacred, and would not injure them on any account. Cambyses had his men carry the `sacred' animals in front of them to the attack. The Egyptians did not dare to shoot their arrows for fear of wounding the animals, and so Pelusium was stormed successfully. After the taking of the city Cambyses seized the opportunity to show his contempt of the Egyptians. He himself carried a cage of cats in front of him upon his horse, and hurled them with insulting taunts and laughter, in to the faces of his foes.

After capturing Egypt, Cambyses took the Throne name Mesut-i-re (Mesuti-Ra), meaning "Offspring of Re". Though the Persians would rule Egypt for the next 193 years until Alexander the Great defeated Darius III and conquered Egypt in 332 BC, Cambyses II's victory would bring to an end (for the most part) Egyptians truly ruling Egyptians until the mid 20th century, when Egypt finally shrugged off colonial rule.

We know very little about Cambyses II through contemporary texts, but his reputation as a mad tyrannical despot has come down to us in the writings of the Greek historian Herodotus (440 BC) and a Jewish document from 407 BC known as 'The Demotic Chronicle' which speaks of the Persian king destroying all the temples of the Egyptian gods. However, it must be repeatedly noted that the Greeks shared no love for the Persians. Herodotus informs us that Cambyses II was a monster of cruelty and impiety.

Herodotus gives us three tales as to why the Persians invaded Egypt. In one, Cambyses II had requested an Egyptian princess for a wife, or actually a concubine, and was angered when he found that he had been sent a lady of second rate standing. In another, it turns out that he was the bastard son of Nitetis, daughter of the Saite (from Sais) king Apries, and therefore half Egyptian anyway, whereas the third story provides that Cambyses II, at the age of ten, made a promise to his mother (who is now Cassandane) that he would "turn Egypt upside down" to avenge a slight paid to her. However, Ctesias of Cnidus states that his mother was Amytis, the daughter of the last king of independent Media so we are really unsure of that side of his parentage. While even Herodotus doubts all of these stories, and given the fact that his father had already planned one invasion of Egypt, the stories do in fact reflect the later Greek bias towards his Persian dynasty.

Regardless of Cambyses II's reason for his invasion of Egypt, Herodotus notes how the Persians easily entered Egypt across the desert. They were advised by the defecting mercenary general, Phanes of Halicarnassus, to employ the Bedouins as guides. However, Phanes had left his two sons in Egypt. We are told that for his treachery, as the armies of the Persians and the mercenary army of the Egyptians met, his sons were bought out in front of the Egyptian army where they could be seen by their father, and there throats were slit over a large bowl. Afterwards, Herodotus tells us that water and wine were added to the contents of the bowl and drunk by every man in the Egyptian force.

This did not stop the ensuing battle at Pelusium, Greek pelos, which was the gateway to Egypt. Its location on Egypt's eastern boundary, meant that it was an important trading post was well and also of immense strategic importance. It was the starting point for Egyptian expeditions to Asia and an entry point for foreign invaders.

Here, the Egyptian forces were routed in the battle and fled back to Memphis. Apparently Psamtek III managed to escape the ensuing besiege of the Egyptian capital, only to be captured a short time afterwards and was carried off to Susa in chains. Herodotus goes on to tell us of all the outrages that Cambyses II then inflicted on the Egyptians, not only including the stabbing of a sacred Apis bull and his subsequent burial at the Serapeum in Saqqara, but also the desecration and deliberate burning of the embalmed body of Amasis (a story that has been partly evidenced by destruction of some of Amasis' inscriptions) and the banishment of other Egyptian opponents.

The story of Cambyses II's fit of jealousy towards the Apis bull, whether true or simply Greek propaganda, was intended to reflect his personal failures as a monarch and military leader. In the three short years of his rule over Egypt he personally led a disastrous campaign up the River Nile into Ethiopia. There, we are told, his ill-prepared mercenary army was so meagerly supplied with food that they were forced to eat the flesh of their own colleagues as their supplies ran out in the Nubian desert. The Persian army returned northwards in abject humiliation having failed even to encounter their enemy in battle.

Then, of course, there is also the mystery of his lost army, some fifty thousand strong, that vanished in the Western Desert on their way to the Siwa Oasis along with all their weapons and other equipment, never to be heard of again. Cambyses II had also planned a military campaign against Carthage, but this too was aborted because, on this occasion, the king's Phoenician sea captains refused to attack their kinfolk who had founded the Carthagian colony towards the end of the 8th century BC. In fact, the conquest of Egypt was Cambyses' only spectacular military success in his seven years of troubled rule over the Persian empire.

However, we are told that when the Persians at home received news of Cambyses' several military disasters, some of the most influential nobles revolted, swearing allegiance to the king's younger brother Bardiya. With their support, the pretender to the great throne of Cyrus seized power in July 522 BC as Cambyses II was returning home.

The story is told that, on hearing of this revolt, and in haste to mount his horse to swiftly finish the journey home, Cambyses II managed to stab himself in the thigh with his own dagger. At that moment, he began to recall an Egyptian prophecy told to him by the priests of Buto in which it was predicted that the king would die in Ecbatana. Cambyses II had thought that the Persian summer capital of Ecbatana had been meant and that he would therefore die in old age. But now he realized that the prophecy had been fulfilled in a very different way here in Syrian Ecbatana.

Still enveloped in his dark and disturbed mood, Cambyses II decided that his fate had been sealed and simply lay down to await his end. The wound soon became gangrenous and the king died in early August of 522 BC. However, it should be noted that other references tell us that Cambyses II had his brother murdered even prior to his expedition to Egypt, but apparently if it was not Bardiya (though there is speculation that Cambyses II's servants perhaps did not kill his brother as ordered), there seems to have definitely been an usurper to the throne, perhaps claiming to be his brother, who we are told was killed secretly.

Cambyses II

Modern Egyptologists believe that many of these accounts are rather biased, and that Cambyses II's rule was perhaps not nearly so traumatic as Herodotus, who wrote his history only about 75 years after Cambyses II's demise, would have us believe. In reality, the Saite dynasty had all but completely collapsed, and it is likely that with Psamtek III's (Psammetichus III) capture by the Persians, Cambyses II simply took charge of the country. The Egyptians were particularly isolated at this time in their history, having seen there Greek allies defect, including not only Phanes, but Polycrates of Samos. In addition, many of Egypt's minorities, such as the Jewish community at Elephantine and even certain elements within the Egyptian aristocracy, seem to have even welcomed Cambyses II's rule.

A depiction of Cambyses II worshipping the Apris Bull

The Egyptian evidence that we do have depicts a ruler anxious to avoid offending Egyptian susceptibilities who at least presented himself as an Egyptian king in all respects. It is even possible that the pillaging of Egyptian towns told to us by Greek sources never occurred at all. In an inscription on the statue of Udjadhorresnet, a Saite priest and doctor, as well as a former naval officer, we learn that Cambyses II was prepared to work with and promote native Egyptians to assist in government, and that he showed at least some respect for Egyptian religion. For example, regardless of the death of the Apris Bull, it should be noted that the animal's burial was held with proper pomp, ceremony and respect. Indeed, Cambyses II continued Egyptian policy regarding sanctuaries and national cults, confirmed by his building work in the Wadi Hammamat and at a few other Egyptian temples.

The statue recording the autobiography of Udjadhorresnet

Udjadhorresnet goes on to say in his autobiography written on a naophorous statue now in the Vatican collection at Rome, that he introduced Cambyses II to Egyptian culture so that he might take on the appearance of a traditional Egyptian Pharaoh.

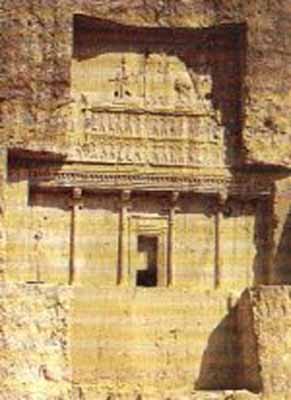

However, even though Cambyses II had his name written in a kingly Egyptian cartouche, he did remained very Persian, and was buried at Takht-i-Rustam near Persepolis (Iran). It has been suggested that Cambyses II may have originally followed a traditional Persian policy of reconciliation in the footsteps of their conquests. In deed, it may be that Cambyses II's rule began well enough, but with the his defeats and losses, his mood may very well have turned darker with time, along with his actions.

We do know that there was a short lived revolt which broke out in Egypt after Cambyses II died in 522 BC, but the independence was lost almost immediately to his successor, a distant relative and an officer in Cambyses II's army, named Darius. The dynasty of Persian rulers who then ruled Egypt did so as absentee landlords from afar.

The unfinished tomb of Cambyses II in Iran

The Lost Army of Cambyses II

Within recent years all manner of artifacts and monuments have been discovered in Egypt's Western Desert. Here and there, new discoveries of temples and tombs turn up, even in relatively inhabited areas where more modern structures are often difficult to distinguish from ancient ruins. It is a place where the shifting sands can uncover whole new archaeological worlds, and so vast that no more than very small regions are ever investigated systematically by Egyptologists. In fact, most discoveries if not almost all are made by accident, so Egypt antiquity officials must remain ever alert to those who bring them an inscribed stone unearthed beneath a house, or a textile fragment found in the sand.

Lately, there has been considerable petroleum excavation in the Western Desert. Anyone traveling the main route between the near oasis will see this activity, but the exploration for oil stretched much deeper into the Western Desert. It is not surprising that they have come upon a few archaeological finds, and it is not unlikely that they will come across others. Very recently, when a geological team from the Helwan University geologists found themselves walking through dunes littered with fragments of textiles, daggers, arrow-heads, and the bleached bones of the men to whom all these trappings belonged, they reported the discovery to the antiquity service.

Mohammed al-Saghir of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) now believes that this accidental find may very well be at least remnants of the mysterious Lost Army of Cambyses II, and he is now organizing a mission to investigate the site more thoroughly. If he is successful and the discovery is that of Cambyses II's 50,000 strong lost army, than it will not only answer some ancient mysteries, but will probably also provide us with a rich source of information on the Persian military of that time, and maybe even expand our knowledge of Cambyses II himself.

The Persian armed forces consisted of many elements, including companies of foreign mercenaries such as Greeks, Phoenicians, Carians, Cilicians, Medes and Syrians. Hence, if this is not another false lead, we may expect excellent preservation of helmets, leather corselets, cloth garments, spears, bows, swords and daggers - a veritable treasure trove of military memorabilia. The rations and support equipment will all be there, ready for detailed analysis.

However, it should be noted that some Egyptologists question the very existence of such an army, rather believing that the whole affair was simply a fable told by a very prejudiced Greek.

Yet if true, Cambyses II probably sent his army to Siwa Oasis in the Western Desert to seek (or seize) legitimization of his rule from the oracle of Amun, much as Alexander the Great would do in the 4th century BC. However, the army was overtaken by a sandstorm and buried. For centuries adventurers and archaeologists have tried to find the lost army, and at times, tantalizing, though usually false glues have been discovered.

Legitimizing his rule does not fully explain the need for taking such a large army to the Siwa Oasis. Accounts and other resources provide that the priests of the oracle were perhaps posing a danger to Cambyses II's rule, probably encouraging revolt among the native Egyptians. Perhaps the priests felt slighted that Cambyses II had not immediately sought their approval as Alexander the Great would do almost upon his arrival in Egypt. Therefore, it is likely that Cambyses II intended to forces their legitimization of his rule. In fact, some sources believe that his intent was to simply destroy the Oasis completely for their treachery, while it is also know that the army was to continue on after Siwa in order to attack the Libyans.

Yet the Siwa Oasis, the western most of Egypt's Oasis, is much deeper into the desert than others, such as Bahariya, and apparently, like many of Cambyses II's military operations, this one too was ill conceived. Why he so easily entered Egypt with the help of the Bedouins, and than sent such a large force into the desert only to be lost is a mystery.

We know that the army was dispatched from the holy city of Thebes, supported by a great train of pack animals. After a seven day march, it reached the Kharga Oasis and moved on to the last of the near Oasis, the Bahariya, before turning towards the 325 kilometers of desert that separated it from the Siwa Oasis. It would have been a 30 day march through burning heat with no additional sources of water or shade.

According to Herodotus (as later reported to him by the inhabitants of Siwa), after many days of struggle through the soft sand, the troops were resting one morning when calamity struck without warning. "As they were at their breakfast, a wind arose from the south, strong and deadly, bringing with it vast columns of whirling sand, which buried the troops and caused them utterly to disappear." Overwhelmed by the powerful sandstorm, men and animals alike were asphyxiated as they huddled together, gradually being enveloped in a sea of drift-sand.

It was after learning of the loss of his army that, having witnessed the reverence with which the Egyptians regarded the sacred Apis bull of Memphis in a ceremony and believing he was being mocked, he fell into a rage, drew his dagger and plunged it into the bull-calf. However, it seems that he must have latter regretted this action, for the Bull was buried with due reverence.

Cambyses left no heirs, and Darius I, one of his generals, fought his way to sovereignty against many rivals.

Darius I - Darius The Great - was the second ruler of the Twenty-seventh Dynasty. He was king of Persia in 522-486 BC, one of the greatest rulers of the Achaemenid dynasty, who was noted for his administrative genius and for his great building projects. Darius attempted several times to conquer Greece; his fleet was destroyed by a storm in 492, and the Athenians defeated his army at Marathon in 490.

Ascension to monarchy

Darius was the son of Hystaspes, the satrap (provincial governor) of Parthia. The principal contemporary sources for his history are his own inscriptions, especially the great trilingual inscription on the Bisitun (Behistun) rock at the village of the same name, in which he tells how he gained the throne. The accounts of his accession given by the Greek historians Herodotus and Ctesias are in many points obviously derived from this official version but are interwoven with legends.

According to Herodotus, Darius, when a youth, was suspected by Cyrus II the Great (who ruled from 559 to 529 BC) of plotting against the throne. Later Darius was in Egypt with Cambyses II, the son of Cyrus and heir to his kingdom, as a member of the royal bodyguard. After the death of Cambyses in the summer of 522 BC, Darius hastened to Media, where, in September, with the help of six Persian nobles, he killed Bardiya (Smerdis), another son of Cyrus, who had usurped the throne the previous March.

In the Bisitun inscription Darius defended this deed and his own assumption of kingship on the grounds that the usurper was actually Gaumata, a Magian, who had impersonated Bardiya after Bardiya had been murdered secretly by Cambyses. Darius therefore claimed that he was restoring the kingship to the rightful Achaemenid house. He himself, however, belonged to a collateral branch of the royal family, and, as his father and grandfather were alive at his accession, it is unlikely that he was next in line to the throne. Some modern scholars consider that he invented the story of Gaumata in order to justify his actions and that the murdered king was indeed the son of Cyrus.

Darius did not at first gain general recognition but had to impose his rule by force. His assassination of Bardiya was followed, particularly in the eastern provinces, by widespread revolts, which threatened to disrupt the empire. In Susiana, Babylonia, Media, Sagartia, and Margiana, independent governments were set up, most of them by men who claimed to belong to the former ruling families. Babylonia rebelled twice and Susiana three times.

In Persia itself a certain Vahyazdata, who pretended to be Bardiya, gained considerable support. These risings, however, were spontaneous and uncoordinated, and, notwithstanding the small size of his army, Darius and his generals were able to suppress them one by one. In the Bisitun inscription he records that in 19 battles he defeated nine rebel leaders, who appear as his captives on the accompanying relief. By 519 BC, when the third rising in Susiana was put down, he had established his authority in the east.

In 518 Darius visited Egypt, which he lists as a rebel country, perhaps because of the insubordination of its satrap, Aryandes, whom he put to death.

Fortification of the empire

Having restored internal order in the empire, Darius undertook a number of campaigns for the purpose of strengthening his frontiers and checking the incursions of nomadic tribes. In 519 BC he attacked the Scythians east of the Caspian Sea and a few years later conquered the Indus Valley.

In 513, after subduing eastern Thrace and the Getae, he crossed the Danube River into European Scythia, but the Scythian nomads devastated the country as they retreated from him, and he was forced, for lack of supplies, to abandon the campaign.

The satraps of Asia Minor completed the subjugation of Thrace, secured the submission of Macedonia, and captured the Aegean islands of Lemnos and Imbros. Thus, the approaches to Greece were in Persian hands, as was control of the Black Sea grain trade through the straits, the latter being of major importance to the Greek economy.

The conquest of Greece was a logical step to protect Persian rule over the Greeks of Asia Minor from interference by their European kinsmen. According to Herodotus, Darius, before the Scythian campaign, had sent ships to explore the Greek coasts, but he took no military action until 499 BC, when Athens and Eretria supported an Ionian revolt against Persian rule.

After the suppression of this rebellion, Mardonius, Darius' son-in-law, was given charge of an expedition against Athens and Eretria, but the loss of his fleet in a storm off Mount Athos (492 BC) forced him to abandon the operation. In 490 BC another force under Datis, a Mede, destroyed Eretria and enslaved its inhabitants but was defeated by the Athenians at Marathon. Preparations for a third expedition were delayed by an insurrection in Egypt, and Darius died in 486 BC before they were completed.

Darius as an administrator

Although Darius consolidated and added to the conquests of his predecessors, it was as an administrator that he made his greatest contribution to Persian history. He completed the organization of the empire into satrapies, initiated by Cyrus the Great, and fixed the annual tribute due from each province. During his reign, ambitious and far-sighted projects were undertaken to promote imperial trade and commerce.

Coinage, weights, and measures were standardized and land and sea routes developed. An expedition led by Scylax of Caryanda sailed down the Indus River and explored the sea route from its mouth to Egypt, and a canal from the Nile River to the Red Sea, probably begun by the chief of the Egyptian delta lords, Necho I (7th century BC), was repaired and completed.

While measures were thus taken to unite the diverse peoples of the empire by a uniform administration, Darius followed the example of Cyrus in respecting native religious institutions. In Egypt he assumed an Egyptian titulary and gave active support to the cult. He built a temple to the god Amon in the Kharga oasis, endowed the temple at Edfu, and carried out restoration work in other sanctuaries.

He empowered the Egyptians to reestablish the medical school of the temple of Sais, and he ordered his satrap to codify the Egyptian laws in consultation with the native priests. In the Egyptian traditions he was considered as one of the great lawgivers and benefactors of the country. In 519 BC he authorized the Jews to rebuild the Temple at Jerusalem, in accordance with the earlier decree of Cyrus. In the opinion of some authorities, the religious beliefs of Darius himself, as reflected in his inscriptions, show the influence of the teachings of Zoroaster, and the introduction of Zoroastrianism as the state religion of Persia is probably to be attributed to him.

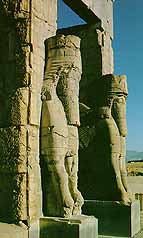

Darius was the greatest royal architect of his dynasty, and during his reign Persian architecture assumed a style that remained unchanged until the end of the empire. In 521 BC he made Susa his administrative capital, where he restored the fortifications and built an audience hall (apadana) and a residential palace.

The foundation inscriptions of his palace describe how he brought materials and craftsmen for the work from all quarters of the empire. At Persepolis, in his native country of Fars (Persis), he founded a new royal residence to replace the earlier capital at Pasargadae.

The fortifications, apadana, council hall, treasury, and a residential palace are to be attributed to him, although not completed in his lifetime. He also built at Ecbana and Babylon.

Darius died while preparing a new expedition against the Greeks; his son and successor, Xerxes I, attempted to fulfill his plan.

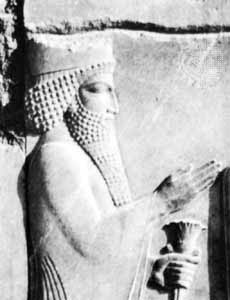

Xerxes I, detail of a bas-relief of the north courtyard in

the treasury at Persepolis, late 6th - early 5th century BC

Xerxes I - (Xerxes the Great) - was the third ruler of the Twenty-seventh Dynasty. His name in Old Persian is Khshayarsha, in the Bible Ahasuerus.

Xerxes became king of Persia at the death of his father Darius the Great in 485, at a time when his father was preparing a new expedition against Greece and had to face an uprising in Egypt. According to Herodotus, the transition was peaceful this time.

Because he was about to leave for Egypt, Darius, following the law of his country had been requested to name his successor and to choose between the elder of his sons, born from a first wife before he was in power, and the first of his sons born after he became king, from a second wife, Atossa, Cyrus' daughter, who had earlier been successively wed to her brothers Cambyses and Smerdis, and which he had married soon after reaching power in order to confirm his legitimacy. Atossa was said to have much power on Darius and he chose her son Xerxes for successor. When his father died, in 486 BC, Xerxes was about 35 years old and had already governed Babylonia for a dozen years.

One of his first concerns upon his accession was to pacify Egypt, where a usurper had been governing for two years. But he was forced to use much stronger methods than had Darius. In 484 BC he ravaged the Delta and chastised the Egyptians.

Xerxes then learned of the revolt of Babylon, where two nationalist pretenders had appeared in swift succession. The second, Shamash-eriba, was conquered by Xerxes' son-in-law, and violent repression ensued: Babylon's fortresses were torn down, its temples pillaged, and the statue of Marduk destroyed; this latter act had great political significance.

Xerxes was no longer able to "take the hand of" (receive the patronage of) the Babylonian god. Whereas Darius had treated Egypt and Babylonia as kingdoms personally united to the Persian Empire (though administered as satrapies), Xerxes acted with a new intransigence.

Having rejected the fiction of personal union, he then abandoned the titles of king of Babylonia and king of Egypt, making himself simply "king of the Persians and the Medes." It was probably the revolt of Babylon, although some authors say it was troubles in Bactria, to which Xerxes alluded in an inscription that proclaimed: "And among these countries (in rebellion) there was one where, previously, daevas had been worshipped. Afterward, through Ahura Mazda's favor, I destroyed this sanctuary of daevas. Let daevas not be worshipped. There, where daevas had been worshipped before, I worshipped Ahura Mazda."

Xerxes thus declared himself the adversary of the daevas, the ancient pre-Zoroastrian gods, and doubtlessly identified the Babylonian gods with these fallen gods of the Aryan religion. The questions arise of whether the destruction of Marduk's statue should be linked with this text proclaiming the destruction of the daeva sanctuaries, of whether Xerxes was a more zealous supporter of Zoroastrianism than was his father, and, indeed, of whether he himself was a Zoroastrian.

It is said that the slaves' lives were much harder during the time of Xerxes. It is not certain whether this is true since Xerxes was much more involved elsewhere and paid little attention to Egypt.

During his reign he put down uprisings in both Egypt and Babylon, but his efforts to invade Europe were thrown back by Greece in 480.

Xerxes was assassinated in 465 BC. Some believe that it was his son who had him assassinated, but there is no proof.

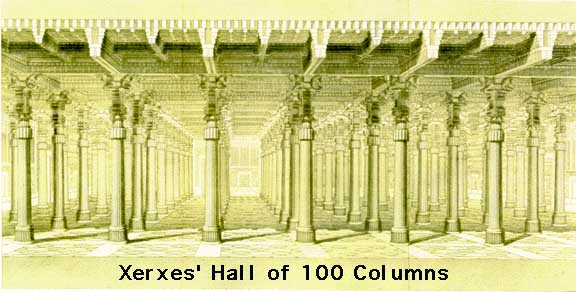

Xerxes' Hall of the 100 Columns is the most impressive

building in the Persepolis Complex. jumble of fallen

columns, column heads, and column bases.

The Gate of Xerxes at Perespolis shows that the Winged Lion was placed at the corner of one entrance. When you stood in front of the gate you saw a lion with four legs and when you were inside the gate you also saw a lion with four legs.

The king of ancient Persia (464-425 BC), of the dynasty of the Achaemenis. Artaxerxes is the Greek form of "Ardashir the Persian." He succeeded his father, Xerxes I , in whose assassination he had no part. The later weakness of the Persian Empire is commonly traced to the reign of Artaxerxes, and there were many uprisings in the provinces.

The revolt of Egypt, aided by the Athenians, was put down (c.455 BC) after years of fighting, and Bactria was pacified. The Athenians sent a fleet under Cimon to aid a rebellion of Cyprus against Persian rule.

The fleet won a victory, but the treaty negotiated by Callias was generally favorable to Persia. Important cultural exchanges occurred between Greece and Persia during Artaxerxes' reign. He was remembered warmly in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah because he authorized their revival of Judaism.

Darius II was the fifth king of the Twenty-seventh Dynasty. 404 B.C., king of ancient Persia (423?-404 B.C.); son of Artaxerxes I and a concubine, hence sometimes called Darius Nothus [Darius the Bastard].

His rule was not popular or successful, and he spent most of his reign in quelling revolts in Syria, Lydia (413), and Media (410).

He lost Egypt (410), but through the diplomacy of Pharnabazus, Tissaphernes, and Cyrus the Younger he secured much influence in Greece in the Peloponnesian War.

Artaxerxes II succeeded Darius, but the succession was challenged by Cyrus the Younger.

During his reign, he did some work on the temple of Amun is the Kharga oasis.

There were also many foreigners in Egypt during this time, mostly Greeks and Jews.

He died in the spring of 404 BC.