Servius Tullius was the legendary sixth king of ancient Rome, and the second of its Etruscan dynasty. He reigned 578-535 BC. Roman and Greek sources describe his servile origins and later marriage to a daughter of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, Rome's first Etruscan king, who was assassinated in 579 BC. Servius was said to have been the first Roman king to accede without election by the Senate, having gained the throne by popular support, at the contrivance of his mother-in-law.

Several traditions describe Servius' father as divine. Livy depicts Servius' mother as a captured Latin princess enslaved by the Romans; her child is chosen as Rome's future king after a ring of fire is seen around his head. The Emperor Claudius discounted such origins and described him as an originally Etruscan mercenary who fought for Caelius Vibenna.

Servius was a popular king, and one of Rome's most significant benefactors. He had military successes against Veii and the Etruscans, and expanded the city to include the Quirinal, Viminal and Esquiline hills. He is credited with the institution of the Compitalia festivals, the building of temples to Fortuna and Diana, and the invention of Rome's first true coinage. Despite the opposition of Rome's patricians, he expanded the Roman franchise and improved the lot and fortune of Rome's lowest classes of citizens and non-citizens.

According to Livy, he reigned for 44 years, until murdered by his treacherous daughter Tullia and son-in-law Tarquinius Superbus. In consequence of this "tragic crime" and his hubristic arrogance as king, Tarquinius was eventually removed. This cleared the way for the abolition of Rome's monarchy and the founding of the Roman Republic, whose groundwork had already been laid by Servius' reforms.

The main literary sources for Servius' life and achievements are the Roman historian Livy (59 BC - AD 17), his near contemporary Dionysius of Halicarnassus, and Plutarch (c.46 - 120 AD); their own sources included works by Quintus Fabius Pictor, Diocles of Peparethus and Quintus Ennius. Livy's sources probably included at least some official state records; he takes pains to arrange his material selectively, within an overarching chronology. Dionysus and Plutarch offer various alternatives not found in Livy, and Livy's own pupil, the etruscologist, historian and emperor Claudius offered yet another, based on Etruscan tradition.

Claims of divine ancestry and divine favor were often attached to charismatic individuals who rose "as if from nowhere" to become dynasts, tyrants and hero-founders in the ancient Mediterranean world. Yet all these legends offer the father as divine, the mother Ð virgin or not Ð as princess of a ruling house, never as slave. The disembodied phallus and its impregnation of a virgin slave of Royal birth are unique to Servius.

Livy and Dionysius ignore or reject the tales of Servius' supernatural virgin birth; though his parents came from a conquered people, both are of noble stock. His ancestry is an accident of fate, and his character and virtues are entirely Roman. He acts on behalf of the Roman people, not for personal gain; these Roman virtues are likely to find favor with the gods, and win the rewards of good fortune.

Nevertheless, the stories of Servius servile birth circulated far beyond Rome, confirmed by Mithridates sneer at Rome's servos vernasque Tuscorum; the details of Servius' servile birth, miraculous conception and links with divine Fortuna were doubtless embellished after his own time, but the core may have been propagated during his reign.

His unconstitutional and seemingly reluctant accession, and his direct appeal to the Roman masses over the heads of the senate may have been interpreted as the rise of a tyrant. Under these circumstances, an extraordinary personal charisma must have been central to his success. When Servius expanded Romes influence and boundaries, and reorganized its citizenship and armies, his "new Rome" was still centered on the Comitium, the casa Romuli of Romulus. Servius became a second Romulus, a benefactor to his people, part human, part divine; but his slave origins remain without parallel, and make him all the more remarkable: for Cornell, this is "the most important single fact about him".

Claudius' story of Servius as an Etruscan named Macstarna was published as an incidental scholarly comment within the Oratio Claudii Caesaris of the Lugdunum Tablet. There is some support for this Etruscan version of Servius, in wall paintings at the Francois Tomb in Etruscan Vulci. They were commissioned some time in the 2nd half of the 4th cent BC. One panel shows heroic Etruscans putting foreign captives to the sword. The victims include a Roman named Gnaeus Tarquinius.

The victors include Aule and Caile Vipinas Ð known to the Romans as the Vibenna brothers Ð and their ally or countryman Macstrna, who seems instrumental in winning the day. Claudius was certain that Macstarna was simply another name for Servius Tullius, who started his career as an Etruscan ally of the Vibenna brothers and helped them settle Rome's Caelian Hill. Claudius' account evidently drew on sources unavailable to his fellow-historians, or rejected by them.

There may have been two different, Servius-like figures, or two different traditions about the same figure. Mcstarna may have been the name of a once celebrated Etruscan hero, or more speculatively, an Etruscan rendering of Roman magister (magistrate). Claudius' "Etruscan Servius" seems less a monarch than a freelance Roman magister, an "archaic condottiere" who placed himself and his own band of armed clients at Vibenna's service, and may later have seized, rather than settled Rome's Caelian Hill.

If the Etruscan Macstarna was identical with the Roman Servius, the latter may have been less monarch then some kind of proto-Republican magistrate given permanent office, perhaps a magister populi, a war-leader, or in Republican parlance, a dictator.[

Before its establishment as a Republic, Rome was ruled by kings (Latin reges, singular rex). In Roman tradition, Rome's founder Romulus was the first. Servius Tullius was the sixth, and his successor Tarquinius Superbus (Tarquin the Proud) was the last. The nature of Roman kingship is unclear; most Roman kings were elected by the senate, as to a lifetime magistracy, but some claimed succession through dynastic or divine right. Some were native Romans, others were foreign. Servius Tullius has been described as "the most complex and enigmatic" of all the Roman kings, and a kind of "proto-Republican magistrate".

Most Roman sources name Servius' mother as Ocrisia, a young noblewoman taken at the Roman siege of Corniculum and brought to Rome, either pregnant by her husband, who was killed at the siege: or as a virgin. She was given to Tanaquil, wife of king Tarquinius, and though slave was treated with the respect due her former status. In one variant, she became wife to a noble client of Tarquinius. In others, she served the domestic rites of the royal hearth as a Vestal Virgin, and on one such occasion, having damped the hearth flames with a sacrificial offering, she was penetrated by a disembodied phallus that rose from the hearth. According to Tanaquil, this was a divine manifestation, either of the household Lar or Vulcan himself. Thus Servius was divinely fathered and already destined for greatness, despite his mother's servile status; for the time being, Tanaquil and Ocrisia kept this a secret.

Servius' birth to a slave of the royal household made him part of Tarquin's extended familia. Ancient sources infer him as protege, rather than adopted son, as he married Tarquinius' and Tanaquil's daughter, named by some sources as Gegania. All sources agree that before his accession, either in his early childhood or later, members of the royal household witnessed a nimbus of fire about his head while he slept, a sign of divine favor, and a great portent. He proved a loyal, responsible son-in-law. When given governmental and military responsibilities, he excelled in both.

The sons of Ancus Marcius, Tarquinius' predecessor as king of Rome, remained angry at Tarquinius during his reign. In their minds, he had usurped their rightful place by taking the crown, although they remained hopeful that they might succeed to the throne after Tarquinius' death. Upon the marriage of Servius to the king's daughter, and the general rise of Servius' public stature, the sons of Ancus began to realise that their prospects of succeeding Tarquinius were diminishing. Accordingly, they decided to have Tarquinius murdered, and attempt to seize the throne. The sons of Ancus hired two of the most ferocious shepherds, who approached the king in the palace and struck his head with an axe.

The king's wife, Tanaquil, immediately ordered the palace to be shut. She attended to the king's wound, but realised that the blow was fatal, and therefore approached Servius and entreated him to seize the throne. Tanaquil then addressed the people of Rome from the palace window, stating that the king was recovering from the blow, and had commanded the people to obey the orders of Servius as if he were king.

For several days thereafter, Servius carried out the functions of the king, appearing on the throne wearing the royal toga trabea, and with lictors. The death of Tarquin then became public knowledge, and the senate elected Servius as king. This was the first occasion that the people of Rome were not involved in the election of the king. Servius cemented his authority supported by a strong guard, and the sons of Ancus fled into exile to Suessa Pometia. In Plutarch, he consented to the kingship only at the death-bed insistence of Tanaquil, not for his own advantage but for the benefit of the Roman people.

Early in his reign, Servius warred against Veii and the Etruscans. He is said to have shown valour in the campaign, and to have routed a great army of the enemy. The war helped him to cement his position at Rome. According to the Fasti Triumphales, Servius celebrated three triumphs over the Etruscans, including on 25 November 571 BC and 25 May 567 BC (the date of the third triumph is not legible on the Fasti).

As Rome's population was enlarged by treaty and conquest, Servius formed a comitia centuriata to replace Rome's comitia curiata as its central legislative body. This required the development of a census to determine voting rights among an expanded and culturally diverse population. People were assembled by tribe in the Campus Martius. Under oath, each man told his name, address, social rank, family members, servants, tenants, and property to the registrar.

Land, wealth and the ability to muster arms for military service remained the major qualifications, and provided the basis for traditionally Servian social classifications; Servius is credited as Rome's first censor. Neither the census nor the classification significantly altered social status in Rome. Servius required a minimum wealth qualification of 800,000 sesterces for Senators, and a half of this for equites ("knights").

Rome's expanded voting population was thus divided into classes according to age, wealth and occupation. These classes were further subdivided into centuriae, or centuries.

The comitia centuriata met when summoned by the Senate to vote on legislation. Each century had some vote; the order of voting was determined by the number of centuries within a class, with the largest voting first. If these classes failed to reach unanimity, others were convened to break the deadlock; those with the most centuries met most frequently and had the most power. The classes are as follows:

2nd: 75,000 sesterces in assets. 10 centuries of older men and 10 of younger.

3rd: 50,000 sesterces in assets. 10 of older, 10 of younger.

4th: 25,000 sesterces in assets. 10 older, 10 younger.

5th: 11,000 sesterces in assets. 30 centuries of specific types of artisan, such as 3 of carpenters.

6th, or proletarii: No estate. One century.

Archaic society at Rome was divided into three ancestral tribes: the Ramnes, the Tities, and the Luceres, further divided into 30 curiae and held to represent the entire populus Romanus (Roman people). Servius created a four-part division of Rome into regiones, "quarters" that remained in use until 7 BC, when Augustus redistricted the city into 14 new regiones.

Before Servius Tullius, the Ramnes were Latins who lived on the Palatine, the Tities were Sabines who lived on the Quirinal and Viminal, and the Luceres were Etruscans who lived on the Caelian. These tribes and their curiae were further divided into approximately 200 gentes (clans). Each clan contributed one senator ("elder") to the deliberative and consultative body of the Senate, who advised the rex (king) and devised laws in his name. These laws required the approval of the 30 curiae into which the three tribes were divided; the curiae met as the comitia curiata ("the going together of the curiae") to vote on new laws or their amendments, probably one curia at a time, and probably by voice ("yes" or "no").

The senators were the patres (fathers) of their clans. In time Rome was flooded with people not belonging to any of the gentes and who lived in districts around the three established. They had no say in the government. These Italic peoples became the plebs, from an Proto-Indo-European root *ple-, "fill", in the sense of multitude. The three original clans "of the fathers" became the patricii, the "patricians."

By the time of Servius the patricii had become the minority, excluding the majority from a role in government. In order to correct the imbalance, Servius moved the pomerium, the sacred boundary of the city as established by Romulus, to add to the existing hill districts, thus creating the Seven Hills of Rome, as celebrated in the festival of the Septimontium. The space enclosed he divided into four urban tribes, the Suburana, Esquilina, Collina, and Palatina.

The redistricting brought new families into the social structure. It isn't clear that they received their own curiae; probably not, as Servius innovated a new class system. Their assemblies met on the same field and took over most functions of the curiae, and yet the curiae continued to exist.

Servius established the Roman army's centuria system and its order of battle, based on the civilian classifications established for his census. The military selection process picked men from civilian centuriae and slipped them into military ones. Their function depended on their age, experience, and the equipment they could afford; the wealthier men of combat age were armed as hoplites, heavy infantry with helmet, greaves, breastplate, shields (clipeus), and spears (hastae). Each battle line in the phalanx formation was composed of a single class.

Specialists were chosen from the 5th class. Officers were not part of the class selection process but were picked beforehand, often by vote of the civilian century.

Servius is credited with the foundation of Diana's temple on the Aventine Hill to mark the foundation of the so-called Latin League. Roman tradition associated the Aventine with the ancient kingdom of Alba Longa: Remus, the murdered bother of Romulus in Rome's founding-myth): the Sabines who were thought to have been settled there by Romulus: the Latins resettled there once defeated by Ancus Marcius, Rome's fourth legendary king: and a series of actual or threatened secessions by Rome's plebeians.

Servius' traditional birth-mythos and social reforms appear to justify his foundation of Compitalia, celebrated by the local communities of his re-organized vici.

He expanded the city to include the Quirinal Hill and the Viminal Hill. He expanded the settlement on the Esquiline Hill, and moved his own residence there to increase its reputation. He also built a rampart, moat and wall around the city and expanded the pomerium.

In modern Rome, an ancient portion of surviving wall is attributed him, the remainder supposedly being rebuilt after the sack of Rome in 390/387 BC by the Gauls. No firm evidence can be offered in support of either attribution.[

Servius Tullius arranged the marriage of his two daughters to the two sons of his predecessor Lucius Tarquinius Priscus. The sons were named Lucius Tarquinius and Aruns Tarquinius. According to Livy, the younger of the two daughters had the fiercer disposition, and yet she was married to Aruns, who was the milder of the two sons. "Tarquin and the younger Tullia, did not, in the first instance, become man and wife; for Rome was there by granted a period of reprieve."

Livy says that the similar temperament of the younger Tullia and Lucius Tarquinius drew them to each other, and she inspired Lucius to greater daring. The younger Tullia and Lucius Tarquinius next arranged the murder of their respective siblings, the elder Tullia and Aruns, in quick succession, and Lucius and the younger Tullia were afterwards married.

She then encouraged Lucius Tarquinius to seek the throne. Lucius was convinced, and began to solicit the support of the patrician senators, especially those families who had been given senatorial rank by his father. He bestowed presents upon them, and to them he criticized the king Servius Tullius.

Tarquinius then seized the throne. He went to the senate-house with a group of armed men, sat himself on the throne, and summoned the senators to attend upon King Tarquinius. Tarquin then spoke to the senators, criticizing Servius: for being a slave born of a slave; for failing to be elected by the Senate and the people during an interregnum, as had been the tradition for the election of kings of Rome; for being gifted the throne by a woman; for favoring the lower classes of Rome over the wealthy and for taking the land of the upper classes for distribution to the poor; and for instituting the census so that the wealth of the upper classes might be exposed in order to excite popular envy.

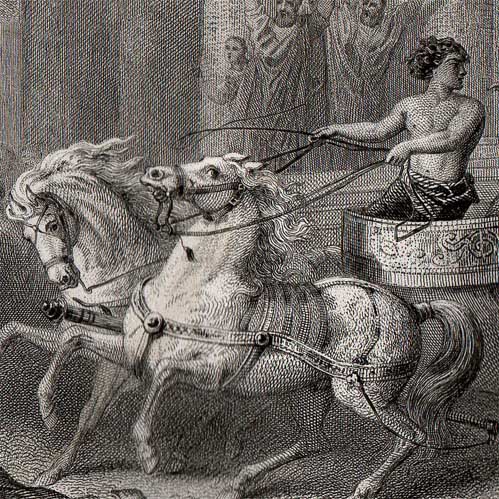

When Servius Tullius arrived at the senate-house to defend his position, Tarquinius threw him down the steps. Servius returned home, but was murdered in the streets of Rome by a group of men sent by Tarquin, possibly on the advice of Tullia. Tullia then drove in her chariot to the senate house, where she hailed her husband as king. He ordered her to return home, away from the tumult.

She drove along the Cyprian street, where the king had been murdered, and turned towards the Orbian Hill, in the direction of the Esquiline Hill. There she encountered her father's body and, on a street later to become known as wicked street because of her actions, she drove her chariot over her father's body. Livy also says that she took a part of her father's body, and his blood, and returned with it to her own and her husband's household gods, and that by the end of her journey she was, herself, covered in the blood. Tarquinius refused to permit Servius to be buried, thereby earning for himself the name "Superbus", translated as 'proud'.

For Livy, Servius' death is a "tragic crime" (tragicum scelus), a dark episode in Rome's history and just cause for the abolition of the monarchy. Servius thus becomes the last of Rome's benevolent kings; the place of this outrage Ð which Livy seems to suggest as a crossroads Ð is known thereafter as Vicus Sceleratus (street of shame, infamy or crime). His murder is parricide, the worst of all crimes. This morally justifies Tarquin's eventual expulsion and the abolition of Rome's aberrant, "un-Roman" monarchy. Livy's Republic is partly founded on the achievements and death of Rome's last benevolent king.

ALPHABETICAL INDEX OF ALL FILES