Various types of aerial surveillance methods were used by UNESCO to create an aerial picture of Tiwanaku. Lidar, aerial photography, drones, and terrestrial laser scanning were all used in this process. Data concluded from this research includes topographical maps that show the principal structures at the site along with mapping of multiple structures in the Mollo Kuntu area. Over 300 million data points were placed from these methods and have helped redefine main structures that have not fully been excavated such as the Puma Punku. Natural foliage covers many megalithic monuments yet to be discovered and excavated as researchers piece together the story of this land and people who lived there long ago.

Tiwanaku (Spanish: Tiahuanaco or Tiahuanacu) is a Pre-Columbian archaeological site in western Bolivia, near Lake Titicaca, about 70 kilometers from La Paz, and it is one of the largest sites in South America. Surface remains currently cover around 4 square kilometers and include decorated ceramics, monumental structures, and megalithic blocks. It has been conservatively estimated that the site was inhabited by 10,000 to 20,000 people in AD 800.

The site was first recorded in written history in 1549 by Spanish conquistador Pedro Cieza de Leon while searching for the southern Inca capital of Qullasuyu.

Jesuit chronicler of Peru Bernabe Cobo reported that Tiwanaku's name once was taypiqala, which is Aymara meaning "stone in the center", alluding to the belief that it lay at the center of the world. The name by which Tiwanaku was known to its inhabitants may have been lost as they had no written language. Heggarty and Beresford-Jones suggest that the Puquina language is most likely to have been the language of Tiwanaku.

The city and its inhabitants left no written history, and modern local people know little about the city and its activities. An archaeologically based theory asserts that around AD 400, Tiwanaku went from being a locally dominant force to a predatory state. Tiwanaku expanded its reaches into the Yungas and brought its culture and way of life to many other cultures in Peru, Bolivia, and Chile. However, Tiwanaku was not exclusively a violent culture. In order to expand its reach, Tiwanaku used politics to create colonies, negotiate trade agreements (which made the other cultures rather dependent), and establish state cults.

Many others were drawn into the Tiwanaku empire due to religious beliefs as Tiwanaku never ceased being a religious center. Force was rarely necessary for the empire to expand, but on the northern end of the Basin resistance was present. There is evidence that bases of some statues were taken from other cultures and carried all the way back to the capital city of Tiwanaku where the stones were placed in a subordinate position to the Gods of the Tiwanaku in order to display the power Tiwanaku held over many.

Among the times that Tiwanaku expressed violence were dedications made on top of building known as the Akipana. Here people were disemboweled and torn apart shortly after death and laid out for all to see. It is speculated that this ritual was a form of dedication to the gods. Research showed that one man who was dedicated was not a native to the Titicaca Basin, leaving room to think that dedications were most likely not of people originally within the society.

The community grew to urban proportions between AD 600 and AD 800, becoming an important regional power in the southern Andes. According to early estimates, at its maximum extent, the city covered approximately 6.5 square kilometers, and had between 15,000 - 30,000 inhabitants.

However, satellite imaging was used recently to map the extent of fossilized suka kollus across the three primary valleys of Tiwanaku, arriving at population-carrying capacity estimates of anywhere between 285,000 and 1,482,000 people.

The empire continued to grow, absorbing cultures rather than eradicating them. William H. Isbell states that "Tiahuanaco underwent a dramatic transformation between AD 600 and 700 that established new monumental standards for civic architecture and greatly increased the resident population."

Archaeologists note a dramatic adoption of Tiwanaku ceramics in the cultures who became part of the Tiwanaku empire. Tiwanaku gained its power through the trade it implemented between all of the cities within its empire.

The elites gained their status by control of the surplus of food obtained from all regions and redistributed among all the people. Control of llama herds became very significant to Tiwanaku, as they were essential for carrying goods back and forth between the center and the periphery. The animals may also have symbolized the distance between the commoners and the elites.

The elites' power continued to grow along with the surplus of resources until about AD 950. At this time a dramatic shift in climate occurred. A significant drop in precipitation occurred in the Titicaca Basin, with some archaeologists venturing to suggest a great drought. As the rain became less and less many of the cities furthest away from Lake Titicaca began to produce fewer crops to give to the elites.

As the surplus of food dropped, the elites power began to fall. Due to the resiliency of the raised fields, the capital city became the last place of production, but in the end even the intelligent design of the fields was no match for the weather. Tiwanaku disappeared around AD 1000 because food production, the empire's source of power and authority, dried up. The land was not inhabited again for many years. In isolated places, some remnants of the Tiwanaku people, like the Uros, may have survived until today.

Beyond the northern frontier of the Tiwanaku state a new power started to emerge in the beginning of the 13th century, the Inca Empire.

In 1445 Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui (the ninth Inca) began conquest of the Titicaca regions. He incorporated and developed what was left from the Tiwanaku patterns of culture, and the Inca officials were superimposed upon the existing local officials. Quechua was made the official language and sun worship the official religion. So, the last traces of the Tiwanaku civilization were integrated or deleted.

The dating of the site has been significantly refined over the last century. From 1910 to 1945, Arthur Posnansky maintained that the site was 11,000-17,000 years old based on comparisons to geological eras and archaeoastronomy.

Beginning in the 1970s, Carlos Ponce Sanginés proposed the site was first occupied around 1580 BC, the site's oldest radiocarbon date. This date is still seen in some publications and museums in Bolivia.

Since the 1980s, researchers have recognized this date as unreliable, leading to the consensus that the site is no older than 200 or 300 BC. More recently, a statistical assessment of reliable radiocarbon dates estimates that the site was founded around AD 110 (50-170, 68% probability), a date supported by the lack of ceramic styles from earlier periods.

Tiwanaku began its steady growth in the early centuries of the first millennium AD. From approximately 375 to 700 AD, this Andean city grew to significance. At its height, the city of Tiwanaku spanned an area of roughly 4 square kilometers (1.5 square miles) and had a population greater than 10,000 individuals. The growth of the city was due to its complex agropastoral economy, supported by trade.

The site appeared to have collapsed around 1000 AD, however the reasoning behind this is still open to debate. Recent studies by geologist Elliott Arnold of the University of Pittsburgh have shown evidence of a greater amount of aridity in the region around the time of collapse. A drought in the region would have affected local systems of agriculture and likely played a role in the collapse of Tiwanaku.

The area around Tiwanaku may have been inhabited as early as 1500 BC as a small agriculturally-based village. Most research, though, is based around the Tiwanaku IV and V periods between AD 300 and AD 1000, during which Tiwanaku grew significantly in power.

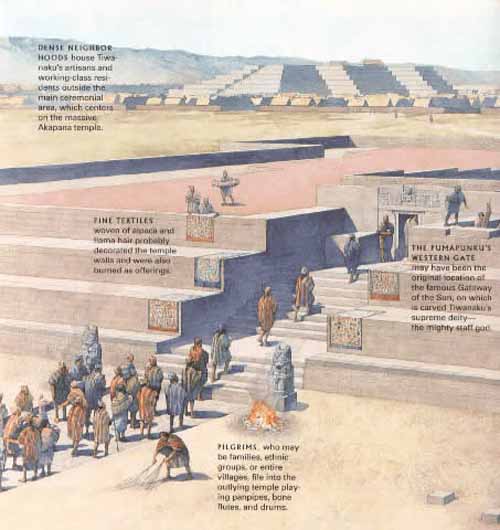

During the time period between 300 BC and AD 300 Tiwanaku is thought to have been a moral and cosmological center to which many people made pilgrimages. The ideas of cosmological prestige are the precursors to Tiwanaku's powerful empire.

Tiwanaku's location between the lake and dry highlands provided key resources of fish, wild birds, plants, and herding grounds for camelidae, particularly llamas. The Titicaca Basin is the most productive environment in the area with predictable and abundant rainfall, which the Tiwanaku culture learned to harness and use in their farming. As one goes further east, the Altiplano is an area of very dry arid land.

The high altitude Titicaca Basin required the development of a distinctive farming technique known as "flooded-raised field" agriculture (suka kollus). They comprised a significant percentage of the agriculture in the region, along with irrigated fields, pasture, terraced fields and qochas (artificial ponds) farming.

Artificially raised planting mounds are separated by shallow canals filled with water. The canals supply moisture for growing crops, but they also absorb heat from solar radiation during the day. This heat is gradually emitted during the bitterly cold nights that often produce frost, endemic to the region, providing thermal insulation.

Traces of landscape management were also found in the Llanos de Moxos region (Amazonian food plains of the Moxos).

Over time, the canals also were used to farm edible fish, and the resulting canal sludge was dredged for fertilizer. The fields grew to cover nearly the entire surface of the lake and although they were not uniform in size or shape, all had the same primary function.

Though labor-intensive, suka kollus produce impressive yields. While traditional agriculture in the region typically yields 2.4 metric tons of potatoes per hectare, and modern agriculture (with artificial fertilizers and pesticides) yields about 14.5 metric tons per hectare, suka kollu agriculture yields an average of 21 tons per hectare.

Significantly, the experimental fields recreated in the 1980s by University of Chicago's Alan Kolata and Oswaldo Rivera suffered only a 10% decrease in production following a 1988 freeze that killed 70-90% of the rest of the region's production. This kind of protection against killing frosts in an agrarian civilization is an invaluable asset. For these reasons, the importance of suka kollus cannot be overstated.

As the population grew occupational niches were created where each member of the society knew how to do their job and relied on the elites of the empire to provide all of the commoners with all the resources that would fulfill their needs.

Little is known of the 30,000 to 60,000 urban dwellers or of the city's crafts or administrative functions. We also know little about the storage system that was required for the bounty of surplus foods from the agricultural fields, the vast llama herds on the Poona, and the abundant fish caught in the lake. The core of this imperial capital was surrounded by a moat that restricted access to the temples and areas frequented by royalty.

Some occupations include agriculturists, herders, pastoralists, etc. Along with this separation of occupations, there was also a hierarchal stratification within the empire.

The elite of Tiwanaku lived inside four walls that were surrounded by a moat. This moat, some believe, was to create the image of a sacred island. Inside the walls there were many images of human origin that only the elites were privileged to, despite the fact that images represent the beginning of all humans not only the elite. Commoners may have only ever entered this structure for ceremonial purposes since it was home to the holiest of shrines.

The people of Tiwanaku held a tight relationship with the Wari culture. The Wari and Tiwanaku civilizations shared the same iconography, referred to as the "Southern Andean Iconographic Series".

The relationship between the two civilizations is presumed to be trade based or military based. The Wari aren't the only other civilization that Tiwanaku could have had contact with. Inca cities also contained similar types of architecture Infrastructure seen in Tiwanaku. From this it can be expected that the Inca took some inspiration from the city of Tiwanaku and other early civilizations in the Andean basin.

Before the Inca Ruled South America, the Tiwanaku Left Their Mark on the Andes Smithsonian - April 2, 2019

The Tiwanaku artifacts, including gold medallions and stone carvings, were found in the waters around the lake's Island of the Sun. Religious iconography and the location of the objects suggest that pilgrimages played an important role in the development of this early empire - a practice that would later be adopted by the Inca civilization.

Photos: Diving for Ancient Offerings in Lake Titicaca Live Science - April 2, 2019

Archaeologists dove into Lake Titicaca in Bolivia and found artifacts dating to hundreds of years ago, which had been put there as offerings, likely by an elite class of people.

s

Offerings to Supernatural Deities Discovered in Lake Titicaca in the Andes Live Science - April 2, 2019

A team of archaeological divers has uncovered dazzling treasures at the bottom of Lake Titicaca, including a puma carved out of the blue gemstone lapis-lazuli, gold medallions and a turquoise stone pendant. These riches were likely offered to supernatural deities hundreds of years ago by elite people from the Tiwanaku culture, which established the first large state in the Andes Mountains from about 500 to 1100

Tiwanaku sculpture is comprised typically of blocky column-like figures with huge, flat square eyes, and detailed with shallow relief carving. They are often holding ritual objects like the Ponce Stela or the Bennett Monolith. Some have been found holding severed heads such as the figure on the Akapana, possibly a puma-shaman. These images suggest ritual human beheading, which correlate with the discovery of headless skeletons found under the Akapana.

Ceramics and textiles were also present in their art, composed of bright colors and stepped patterns. An important ceramic artifact is the kero, a drinking cup, that was ritually smashed after ceremonies and placed in burials. However, as the empire expanded, ceramics changed in the society.

The earliest ceramics were "coarsely polished, deeply incised brownware and a burnished polychrome incised ware". Later the Qeya style became popular during the Tiwanaku III phase "Typified by vessels of a soft, light brown ceramic paste". These ceramics included libation bowls and bulbous bottom vases.

Examples of textiles are tapestries and tunics. The objects typically depicted herders, effigies, trophy heads, sacrificial victims, and felines. The key to spreading religion and influence from the main site to the satellite centers was through small portable objects that held ritual religious meaning. They were created in wood, engraved bone, and cloth and depicted puma and jaguar effigies, incense burners, carved wooden hallucinogenic snuff tablets, and human portrait vessels. Like the Moche, Tiwanaku portraits had individual characteristics in them.

Tiwanaku monumental architecture is characterized by large stones of exceptional workmanship. In contrast to the masonry style of the later Inca, Tiwanaku stone architecture usually employs rectangular ashlar blocks laid in regular courses, and monumental structures were frequently fitted with elaborate drainage systems.

The drainage systems of the Akapana (a terraced platform mound) and Puma Punka include conduits composed of red sandstone blocks held together by ternary (copper/arsenic/nickel) bronze architectural cramps.

The I-shaped architectural cramps of the Akapana were created by cold hammering of ingots. In contrast, the cramps of the Akapana were created by pouring molten metal into I-shaped sockets.

The blocks have flat faces that do not need to be fitted upon placement because the grooves make it possible for the blocks to be shifted by ropes into place.

The main architectural appeal of the site comes from the carved images on the blocks along with carved doorways and giant stone monoliths. The stone used to build Tiwanaku was quarried and then transported 40 km or more to the city.

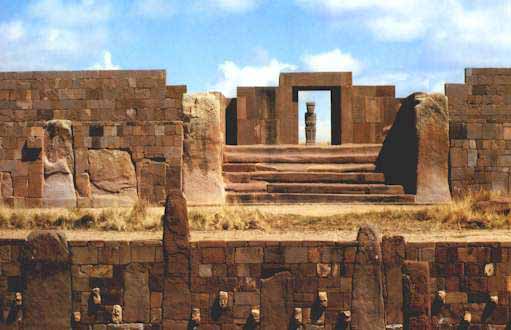

The most important edifice for dating purposes is the Kalasasaya ("Place of the Vertical Stones"). It is built like a stockade with 12 foot high columns jutting upward at intervals, each of these being carved into human figures.

The megalithic entrance to the Kalasaya mound is here seen from the Sunken Courtyard viewing west. The Kalasaya stairway is a well-worn megalith, a single block of carved sandstone. Like the Kalasaya mound, the Sunken Courtyard is walled by standing stones and masonry infill. In this case the stones are smaller and sculptured heads are inset in the walls. Several stelae are placed in the center of the 30 m square courtyard.

The largest terraced step pyramid of the city, the Akapana, was once believed to be a modified hill, and has proven to be a massive human construction with a base 656 feet square and a height of 55.8 feet. It is aligned perfectly with the cardinal directions. Its base is formed of beautifully cut and joined facing stone blocks. Within the cut- stone retaining walls are six T- shaped terraces with vertical stone pillars, an architectural technique that is also used in most of the other Tiwanaku monuments. It originally had a covering of smooth Andesite stone, but 90% of that has disappeared due to weathering. The ruinous state of the pyramid is due to its being used as a stone quarry for later buildings at La Paz. Its interior is honeycombed with shafts in a complicated grid pattern, which incorporates a system of weirs used to direct water from a tank on top, going through a series of levels,and finally ending up in a stone canal surrounding the pyramid. On the summit of the Akapana there was a sunken court with an area 164 feet square serviced by a subterranean drainage system that remains unexplained.

Associated with the Akapana are four temples: the Semi-subterranean, the Kalasasaya, the Putuni, and the Kheri Kala. The first of these, the Semi-subterranean Temple, was studded with sculptured stone heads set into cut-stone facing walls and in the middle of the court was located a now-famous monolithic stela. Named for archaeologist Wendell C. Bennett who conducted the first archaeological research at Tiwanaku in the 1930's, the Bennett Stela represents a human figure wearing elaborate clothes and a crown. The ancient Tiwanaku heartland is estimated to have been about 365,000, of whom 115,000 lived in the capital and satellite cities, with the remaining 250,000 engaged in farming, herding, and fishing.

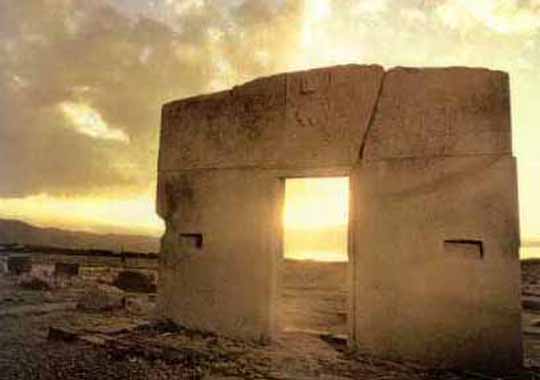

This megatlithic doorway is all that remains of the walls of a building on a small mound near the Kalasaya. Much of the readily accessible masonry at the ruin was used to construct the Catholic church in the village. A nearby railroad bridge also has Tiwanaku stone.

Adjacent to the sunken court, residences of the elite were revealed, while under the patio the remains of a number of seated individuals, believed to have been priests, faced a man with a ceramic vessel that displayed a puma-an animal sacred to the Tiwanaku. Ritual offerings of llamas and ceramics, as well as high-status goods made of copper, silver and obsidian were also encountered in this elite residential area. The cut-stone building foundations supported walls of adobe brick, which have been eroded away by the yearly torrential rains over the centuries.

In 1934 the Peruvianist Wendell C. Bennett carried out several excavations at Tiwanaku. Excavating in the Subterranean Temple he found two large stone images. One was a bearded statue. Depicted are large round eyes, a straight narrow nose and oval mouth. Rays of lightning are carved on the forehead. Strange animals are carved up around the head. It stands over 7 feet tall with arms crossed over an ankle- length tunic, which is decorated with pumas around the hem. Serpents ascend the figure on each side, reminding one of the Feathered Serpent culture-hero known as Quetzalcoatl in Central America.

Beside the bearded statue was a much larger statue Bennett's report as "the large monolithic statue" and is over 24 feet tall. It was sculpted out of red sandstone, and is covered with carved images of various kinds. He holds objects in each hand which are totally unidentifiable, although numerous interpretations have been suggested. The lower half of its body, which is covered with fish-scales (which upon close inspection are actually fish-heads). Immediately one recalls the Mesopotamian deity called Oannes, the man-fish amphibious being who conveyed special knowledge to ancient mankind. The statue has been removed from the site and now stands in a plaza in La Paz.

This monolithic piece of work has a number of designs scattered over its surface, many of which resemble the running winged-figures found on the Gate of the Sun, only with curled-up tails. The "Weeping God" is depicted on the sides of the head of the statue.

There are numerous other statues which have been found at Tiahuanacu, several of which have found their way into various museums. Most have the incomprehensible stiff designs scattered about on their surfaces in the typical Tiahuanacu style. Some are rather large, and others are small. Depictions of toxodons and several other extinct creatures are plentiful at Tiahuanacu. The images of these extinct animals are understandable on pottery and textiles, they could be copied by anyone from the stone monuments dotting the area.

and in the southwest corner is The Idol.

This is one of two large anthropomorphic figures standings in the southwest corner of the Kalasasaya Temple. This one faces the entrance and is placed on the central axis. With the exception of the Sun Gate, it is the most picturesque of the sculptures at Tiahuanacu, since its 7-foot height is almost covered with hieroglyphic-like carvings. No one knows if these carvings represent a form of writing or are merely decorative. The figures resemble those on Easter Island.

The Akapana is the biggest platform on the site measuring 200 meters on each side and 17 meters tall and the largest ashlars of andesite or sandstone weigh over 100 tons.

Originally, the Akapana was thought to have been made from a modified hill, but recent studies have shown that most of the hill is man-made by taking dirt from the moat and packing it behind stone walls.

It is constructed from a mix of tall, upright, and small stones. There are staircases present on the east and west sides with a sunken court 50 meters long between them. Today the area where this would be is an indiscernible hole. The structure was possibly for the shaman-puma relationship or transformation. Tenon puma and human heads stud the upper terraces.

The Akapana East was built on the eastern side of early Tiwanaku and later became a boundary for the ceremonial center and the urban area. It was made of a thick prepared floor of sand and clay and supported a group of buildings. Yellow and red clay were used in different areas for what seems like aesthetic purposes. One major observation was that it was swept clean of all domestic refuse, signaling great importance to the culture.

The Kalasasaya is a large courtyard over three hundred feet long, outlined by a high gateway. It is located to the north of the Akapana and west of the Semi-Subterranean Temple. Within the courtyard is where explorers found the Gateway of the Sun, but it is contested today that this was not its original location.

Near the courtyard is the Semi-Subterranean Temple; a square sunken courtyard that's unique for its north-south rather than east-west axis. The walls are covered with tenon heads of many different styles postulating that it was probably reused for different purposes over time. It was built with walls of sandstone pillars and smaller blocks of Ashlar masonry. There are many more colossal stone statues, gateways and blocks including one that is 7.5 meters tall weighing well over 10 tons.

Within many of the sites structures are impressive gateways; the ones of monumental scale being placed on artificial mounds, platforms, or sunken courts. Many gateways show iconography of "Staffed Gods" that also spreads to some oversized vessels, indicating an importance to the culture. This iconography is most present on the The Gateway of the Sun.

The Gate of the Sun

Winter Solstice

The Gate of the Sun is a stone gateway constructed by the Tiwanaku culture. It is located near Lake Titicaca at about 3,825 m above sea level in La Paz, Bolivia. The gate is approximately 9.8 ft (3.0 m) tall and 13 ft (4.0 m) wide. It was originally constructed by a single piece of stone. The weight is estimated to be 10 tons.

When the gate was originally found, it was lying face down and had a large crack. It stands in the place where it was found, although it is believed that this was not its original location. Gate of the Sun is a valuable monument to the history of art. Some elements of their iconography spread throughout Peru and parts of Bolivia; the engravings that decorate the gate has some astronomic connotations. There have been innumerable interpretations of the inscriptions on Gate of the Sun; many of them believe that it was used as a calendar.

The lintel is carved with 48 winged effigies each in a square, 32 with human faces, and 16 with condor's heads. surrounding a central figure. These faces seem to represent many different races including a white face that looks like an alien gray.

All face the central figure (god). It is a figure of a man with the head surrounded by 24 stripes that represent rays shooting from his face. The styled staffs held by the figure symbolize thunder and lightning.

Some historians believe that the central figure represents the Sun God by the rays of his head, while others identified it with the Inca god Viracocha.

This huge monument is hewn from a single block of stone, and some believe that the strange symbols might represent a calendar, the oldest in the world. A huge monolithic figure, facing east in the direction of sunrise, stands as silent witness to an unknown civilization established around 2200 years ago.

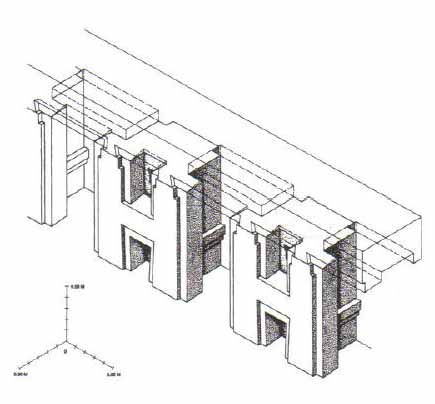

The Gateway of the Sun and others located at Puma Punku are all not complete, missing part of a typical recessed frame known as a chambranle and having sockets for clamps present for additions. These architectural examples, as well as the recently discovered Akapana Gate have a unique detail and skill in stone-cutting that reveal a knowledge of descriptive geometry. The regularity of elements suggest be part of a system of proportions.

Many theories for Tiwanaku's architecture construction have been proposed. One is that they used a luk'a which is a standard measurement of about sixty centimeters. Another argument is for the Pythagorean Ratio. This idea calls for right triangles at a ration of five to four to three used in the gateways to measure all parts. Lastly Protzen and Nair argue that Tiwanaku had a system set for individual elements dependent on context and composition. This is shown in the construction of similar gateways ranging from diminutive to monumental size proving that scaling factors did not affect proportion. With each added element, the individual pieces shifted to fit together.

Throughout their imperial reign, the Tiwanaku shared domination of the Middle Horizon with the Wari. Their culture rose and fell around the same time and was centered 500 miles north in the southern highlands of Peru. The relationship between the two empires is unknown either being cooperative or antagonistic. Definite interaction between the two is proved by their shared iconography in art. Significant elements of both of these styles, the split eye, trophy heads, and staff-bearing profile figures, for example, seem to have been derived from that of the earlier Pukara culture in the northern Titicaca Basin.

The Tiwanaku created a powerful ideology, using previous Andean icons that spread throughout their sphere of influence using extensive trade routes and shamanistic art. Tiwanaku art consisted of legible, outlined figures depicted in curvilinear style with a naturalistic manner, while Wari art used the same symbols in a more abstract, rectilinear style with a militaristic manner.

The structures that have been excavated by researchers at Tiwanaku include the terraced platform mound Akapana, Akapana East, and Pumapunku stepped platforms, the Kalasasaya, the Kantatallita, the Kheri Kala, and Putuni enclosures, and the Semi-Subterranean Temple.

The Akapana is a "half Andean Cross"-shaped structure that is 257 m wide, 197 m broad at its maximum, and 16.5 m tall. At its center appears to have been a sunken court. This was nearly destroyed by a deep looters excavation that extends from the center of this structure to its eastern side. Material from the looter's excavation was dumped off the eastern side of the Akapana. A staircase is present on its western side. Possible residential complexes might have occupied both the northeast and southeast corners of this structure.

Originally, the Akapana was thought to have been developed from a modified hill. Twenty-first-century studies have shown that it is an entirely man-made earthen mound, faced with a mixture of large and small stone blocks. The dirt comprising Akapana appears to have been excavated from the "moat" that surrounds the site. The largest stone block within the Akapana, made of andesite, is estimated to weigh 65.7 tons. Tenon stone blocks in the form of puma and human heads stud the upper terraces.

The Akapana East was built on the eastern side of early Tiwanaku. Later it was considered a boundary between the ceremonial center and the urban area. It was made of a thick, prepared floor of sand and clay, which supported a group of buildings. Yellow and red clay was used in different areas for what seems like aesthetic purposes. It was swept clean of all domestic refuse, signaling its great importance to the culture.

The Pumapunku is a man-made platform built on an east-west axis like the Akapana. It is a T-shaped, terraced earthen platform mound faced with megalithic blocks. It is 167.36 m wide along its north-south axis and 116.7 m broad along its east-west axis and is 5 m tall. Identical 20-meter-wide projections extend 27.6 meters north and south from the northeast and southeast corners of the Pumapunku. Walled and unwalled courts and an esplanade are associated with this structure.

A prominent feature of the Pumapunku is a large stone terrace; it is 6.75 by 38.72 meters in dimension and paved with large stone blocks. It is called the "Plataforma Litica" and contains the largest stone block found in the Tiwanaku site. According to Ponce Sangines, the block is estimated to weigh 131 metric tonnes. The second-largest stone block found within the Pumapunku is estimated to be 85 metric tonnes.

Scattered around the site of the Puma Punku are various types of cut stones. Due to the complexity of the stonework the site is often cited by conspiracy theorists to be a site of ancient alien intervention. These claims are entirely unsubstantiated.

The Kalasasaya is a large courtyard more than 300 feet long, outlined by a high gateway. It is located to the north of the Akapana and west of the Semi-Subterranean Temple. Within the courtyard is where explorers found the Gateway of the Sun. Since the late 20th century, researchers have theorized that this was not the gateway's original location.

Near the courtyard is the Semi-Subterranean Temple; a square sunken courtyard that is unique for its north-south rather than east-west axis. The walls are covered with tenon heads of many different styles, suggesting that the structure was reused for different purposes over time. It was built with walls of sandstone pillars and smaller blocks of Ashlar masonry. The largest stone block in the Kalasasaya is estimated to weigh 26.95 metric tons.

Within many of the site's structures are impressive gateways; the ones of monumental scale are placed on artificial mounds, platforms, or sunken courts. One gateway shows the iconography of a front-facing figure in Staff God pose. This iconography also is used on some oversized vessels, indicating an importance to the culture. The iconography of the Gateway of the Sun called Southern Andean Iconographic Series can be seen on several stone sculptures, Qirus, snuff trays and other Tiwanaku artifacts.

The unique carvings on the top of the Gate of the sun depict animals and other beings. Some have claimed that the symbolism represents a calendar system unique to the people of Tiwanaku, although there is no definitive evidence that this theory is correct.

The Gateway of the Sun and others located at Pumapunku are not complete. They are missing part of a typical recessed frame known as a chambranle, which typically have sockets for clamps to support later additions. These architectural examples, as well as the Akapana Gate, have unique detail and demonstrate high skill in stone-cutting. This reveals a knowledge of descriptive geometry. The regularity of elements suggests they are part of a system of proportions.

Many theories for the skill of Tiwanaku's architectural construction have been proposed. One is that they used a luk’ a, which is a standard measurement of about sixty centimeters. Another argument is for the Pythagorean Ratio. This idea calls for right triangles at a ratio of five to four to three used in the gateways to measure all parts. Lastly, Protzen and Nair argue that Tiwanaku had a system set for individual elements dependent on context and composition. This is shown in the construction of similar gateways ranging from diminutive to monumental size, proving that scaling factors did not affect proportion. With each added element, the individual pieces were shifted to fit together.

As the population grew, occupational niches developed, and people began to specialize in certain skills. There was an increase in artisans, who worked in pottery, jewelry, and textiles. Like the later Inca, the Tiwanaku had few commercial or market institutions. Instead, the culture relied on elite redistribution. That is, the elites of the state controlled essentially all economic output but were expected to provide each commoner with all the resources needed to perform his or her function. Selected occupations include agriculturists, herders, pastoralists, etc. Such separation of occupations was accompanied by hierarchical stratification within the state.

Some authors believe that the elites of Tiwanaku lived inside four walls that were surrounded by a moat. This theory is called "Tiwanaku moat theory". This moat, some believe, was to create the image of a sacred island. Inside the walls were many images devoted to human origin, which only the elites would see. Commoners may have entered this structure only for ceremonial purposes since it was home to the holiest of shrines.

In the 1960s, the Bolivian government initiated an effort to restore the site and reconstruct part of it. The walls of the Kalasasaya are almost all reconstructed. The reconstruction was not sufficiently based on evidence. The reconstruction does not have as high quality of stonework as was present in Tiwanaku. Early visitors compared Kalasasaya to Englands Stonehenge. Ephraim Squier called it "American Stonehenge". Before the reconstruction, it had more of a "Stonehenge"-like appearance as the filler stones between the large stone pillars were all looted.[ As noted, the Gateway of the Sun, now in the Kalasasaya, is believed to have been moved from its original location.

Modern, academically sound archaeological excavations were performed from 1978 through the 1990s by University of Chicago anthropologist Alan Kolata and his Bolivian counterpart, Oswaldo Rivera. Among their contributions are the rediscovery of the suka kollus, accurate dating of the civilization's growth and influence, and evidence for a drought-based collapse of the Tiwanaku civilization.

Archaeologists such as Paul Goldstein have argued that the Tiwanaku empire ranged outside of the altiplano area and into the Moquegua Valley in Peru. Excavations at Omo settlements show signs of similar architecture characteristic of Tiwanaku, such as a temple and terraced mound. Evidence of similar types of cranial vault modification in burials between the Omo site and the main site of Tiwanaku is also being used for this argument.

Today Tiwanaku has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, administered by the Bolivian government.

Recently, the Department of Archaeology of Bolivia (DINAR, directed by Javier Escalante) has been conducting excavations on the terraced platform mound Akapana. The Proyecto Arqueologico Pumapunku-Akapana (Pumapunku-Akapana Archaeological Project, PAPA) run by the University of Pennsylvania, has been excavating in the area surrounding the terraced platform mound for the past few years, and also conducting Ground Penetrating Radar surveys of the area.

In former years, an archaeological field school offered through Harvard's Summer School Program, conducted in the residential area outside the monumental core, has provoked controversy amongst local archaeologists. The program was directed by Gary Urton, of Harvard, who was an expert on quipus, and Alexei Vranich of the University of Pennsylvania.

The controversy was over allowing a team of untrained students to work on the site, even under professional supervision. It was so important that only certified professional archaeologists with documented funding were allowed access. The controversy was charged with nationalistic and political undertones. The Harvard field school lasted for three years, beginning in 2004 and ending in 2007. The project was not renewed in subsequent years, nor was permission sought to do so.

In 2009 state-sponsored restoration work on Akapana was halted due to a complaint from UNESCO. The restoration had consisted of facing the platform mound with adobe, although researchers had not established this as appropriate.

In 2013, marine archaeologists exploring Lake Titicaca's Khoa reef discovered an ancient ceremonial site and lifted artifacts such as a lapis lazuli and ceramic figurines, incense burners and a ceremonial medallion from the lake floor. The artifacts are representative of the lavishness of the ceremonies and the Tiwanaku culture.

When a topographical map of the site was created in 2016 by the use of a drone, a "set of hitherto unknown structures" was revealed. These structures spanned over 411 hectares, and included a stone temple and about one hundred circular or rectangular structures of vast dimensions, which were possibly domestic units.

In many Andean cultures, mountains are venerated and may be considered sacred objects. The site of Tiwanaku is located in the valley between two sacred mountains, Pukara and Chuqi Q’awa. At such temples in ancient times, ceremonies were conducted to honor and pay gratitude to the gods and spirits. They were places of worship and rituals that helped unify Andean peoples through shared symbols and pilgrimage destinations.

Tiwanaku became a center of pre-Columbian religious ceremonies for both the general public and elites. For example, human sacrifice was used in several pre-Columbian civilizations to appease a god in exchange for good fortune. Excavations of the Akapana at Tiwanaku revealed the remains of sacrificial dedications of humans and camelids.

Researchers speculate that the Akapana may also have been used as an astronomical observatory. It was constructed so that it was aligned with the peak of Quimsachata, providing a view of the rotation of the Milky Way from the southern pole. Other structures like Kalasasaya are positioned to provide optimal views of the sunrise on the Equinox, Summer Solstice, and Winter Solstice.

Although the symbolic and functional value of these monuments can only be speculated upon, the Tiwanaku were able to study and interpret the positions of the sun, moon, Milky Way and other celestial bodies well enough to give them a significant role in their architecture.

Aymara legends place Tiwanaku at the center of the universe, probably because of the importance of its geographical location. The Tiwanaku were highly aware of their natural surroundings and would use them and their understanding of astronomy as reference points in their architectural plans.

The most significant landmarks in Tiwanaku are the mountains and Lake Titicaca. The lake level of Lake Titicaca has fluctuated significantly over time. The spiritual importance and location of the lake contributed to the religious significance of Tiwanaku. In the Tiwanaku worldview, Lake Titicaca is the spiritual birthplace of their cosmic beliefs.

According to Incan mythology, Lake Titicaca is the birthplace of Viracocha, who was responsible for creating the sun, moon, people, and the cosmos. In the Kalasasaya at Tiwanaku, carved atop a monolith known as the Gate of the Sun, is a front-facing figure holding a spear-thrower and snuff. Some speculate that this is a representation of Viracocha. However, it is also possible that this figure represents a deity that the Aymara refer to as 'Tunuupa' who, like Viracocha, is associated with legends of creation and destruction.

The Aymara, who are thought to be descendants of the Tiwanaku, have a complex belief system similar to the cosmology of several other Andean civilizations. They believe in the existence of three spaces: Arajpacha, the upper world; Akapacha, the middle or inner world; and Manqhaoacha, the lower world. Often associated with the cosmos and Milky Way, the upper world is considered to be where celestial beings live. The middle world is where all living things are, and the lower world is where life itself is inverted.

As the site has suffered from looting and amateur excavations since shortly after Tiwanaku's fall, archeologists must attempt to interpret it with the understanding that materials have been jumbled and destroyed. This destruction continued during the Spanish conquest and colonial period, and during 19th century and the early 20th century. Other damage was committed by people quarrying stone for building and railroad construction, and target practice by military personnel.

No standing buildings have survived at the modern site. Only public, non-domestic foundations remain, with poorly reconstructed walls. The ashlar blocks used in many of these structures were mass-produced in similar styles so that they could possibly be used for multiple purposes. Throughout the period of the site, certain buildings changed purposes, causing a mix of artifacts found today.

Detailed study of Tiwanaku began on a small scale in the mid-nineteenth century. In the 1860s, Ephraim George Squier visited the ruins and later published maps and sketches completed during his visit. German geologist Alphons Stübel spent nine days in Tiwanaku in 1876, creating a map of the site based on careful measurements. He also made sketches and created paper impressions of carvings and other architectural features. A book containing major photographic documentation was published in 1892 by engineer Georg von Grumbkow, With commentary by archaeologist Max Uhle, this was the first in-depth scientific account of the ruins.

Von Grumbkow had first visited Tiwanaku between the end of 1876 and the beginning of 1877, when he accompanied as a photographer the expedition of French adventurer Theodore Ber, financed by American businessman Henry Meiggs, against Ber's promise of donating the artifacts he will find, on behalf of Meiggs, to Washington's Smithsonian Institution and the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Ber’s expedition was cut short by the violent hostility of the local population, instigated by the Catholic parish priest, but von Grumbkow’s early pictures survive.

Ancient temple could reveal secrets of a lost society that predates the Inca Empire CNN - August 19, 2025

The newly discovered temple complex is located southeast of Lake Titicaca, a region where previous Tiwanaku researchers hadn't focused search efforts

Today Tiwanaku is a UNESCO world heritage site, and is administered by the Bolivian government.

Recently, the Department of Archaeology of Bolivia (DINAR, directed by Javier Escalante) has been conducting excavations on the Akapana pyramid. The Proyecto Arqueologico Puma Punku-Akapana (PAPA, or Puma Punku-Akapana Archaeological Project) run by the University of Pennsylvania, has been excavating in the area surrounding the pyramid for the past few years, and also conducting Ground Penetrating Radar surveys of the area.

In previous years, an archaeological field school offered through Harvard's Summer School Program, conducted in the residential area outside the monumental core, has provoked controversy amongst local archaeologists. The program was directed by Dr. Gary Urton of Harvard, expert in quipu, and Dr. Alexei Vranich of the University of Pennsylvania.

The controversy had to do with fact that permission to excavate Tiwanaku, being such an important site, is only provided to certified professional archaeologists and rarely to independent Bolivian scholars who scarcely can present proof of funding to carry on archaeological research. On that occasion permission was given to Harvard's Summer School to allow a team mostly composed of untrained students to dig the site. The controversy, charged with nationalistic and political undertones that characterized the archaeology of Tiwanaku faded rapidly without any response from the directors, however, the project did not continue in subsequent years.

Because nearby quarries are lacking, scholars marvel at the large blocks used to construct stone structures at Tiwanaku. The red sandstone used in the pyramid have been determined by petrographic analysis to come from a quarry 10 kilometers away - a remarkable distance considering that one of the stones alone weighs over 130 tons. The green andesite stones that were used to create the most elaborate carvings and monoliths originate from the Copacabana peninsula, located across Lake Titicaca. One theory is that these giant andesite stones, which weigh up to 40 tons were transported some 90 kilometers across Lake Titicaca on reed boats, then laboriously dragged another 10 kilometers to the city.

In 2009 state-sponsored restoration work on the Akapana pyramid was halted due to a complaint from UNESCO. The restoration had consisted in plastering the pyramid with adobe, despite it being unclear whether or not the result would bring the pyramid back to its original state.

The origin of many of the megalithic sites found in Central and South America remain unknown yet follow a basic geometric design across the planet.

People study them to find answers to age-old questions about who we are, why we are, and where we are going.

Some believe the human experiment was designed and created by extraterrestrials who came to Earth in the distant past then left saying they will return one day. That storyline is repeated over and over again throughout history as life is about patterns within a simulated reality. They bring hope and the belief in religious icons, whatever their agendas.

UFO sightings have always been in abundance in Central and South America especially at Lake Titicaca replete with the usual legends of creators who came from the sky - some of whom remain here to watch over humanity.

Aliens are, in fact, artificial intelligence. In our current storyline - in the simulation of reality - they present as gray aliens with the ability to shape shift.

The purposes of all of this is to study emotions.

Ancient civilizations came and went (disappeared) - perhaps due to diseases, climate change, natural disasters, blending into surrounding cultures - or they were simply deleted from the simulation.

As you look at climate change and natural disasters today - you remember/understand we are at the end of another story (insert in the simulation) that is about to end.