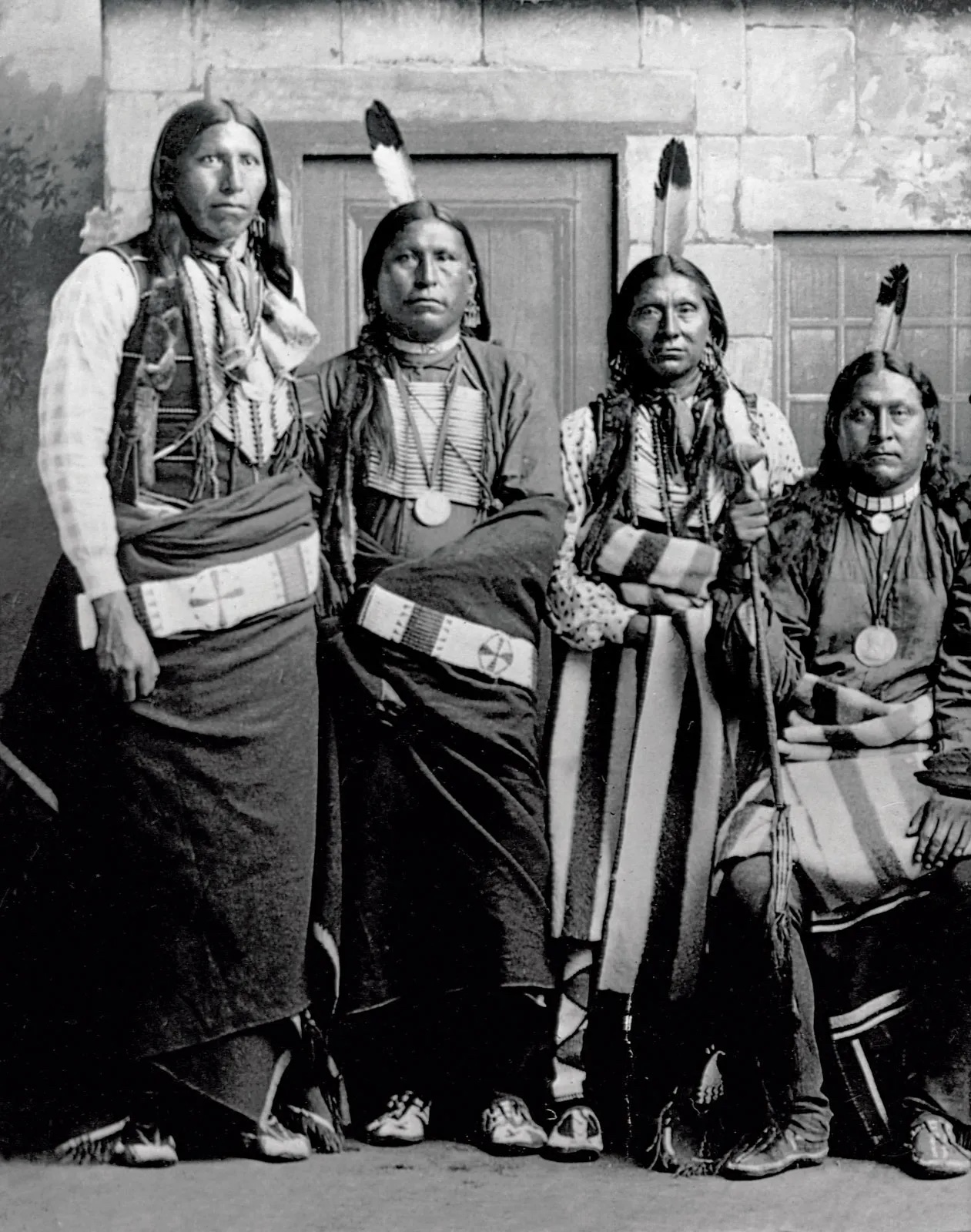

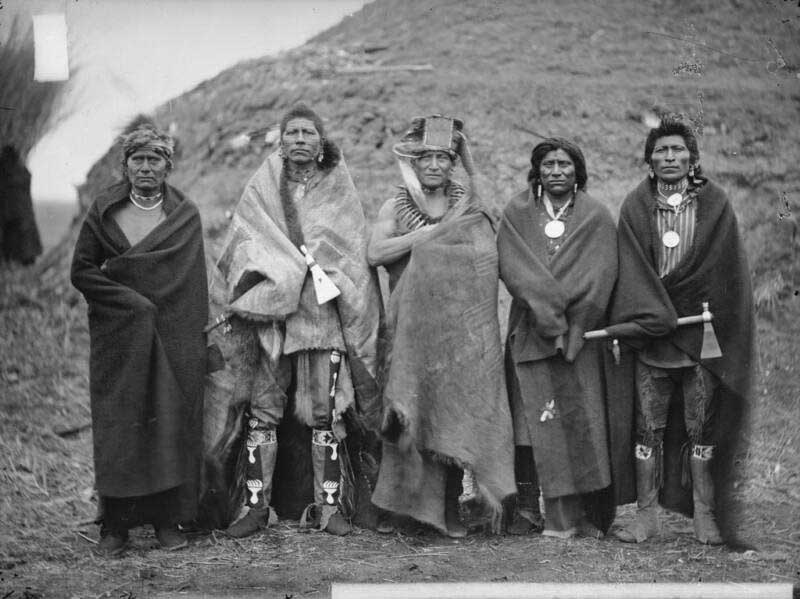

Pawnee people (also Paneassa, Pari, Pariki) are a Caddoan-speaking Native American tribe. They are federally recognized as the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma.

Historically, the Pawnee lived along outlying tributaries of the Missouri River: the Platte, Loup and Republican rivers in present-day Nebraska and in northern Kansas. They lived in permanent earth lodge villages where they farmed. They left the villages on seasonal buffalo hunts, using tipis while traveling.

In the 1830s, the Pawnee numbered about 2,000 people, as they had escaped some of the depredations of exposure to Eurasian infectious diseases. By 1859, their numbers were reduced to about 1,400; however, by 1874 they were back up to 2,000. Still subject to encroachment by the Lakota and European Americans, finally most accepted relocation to a reservation in Indian Territory. This is where most of the enrolled members of the nation live today. Their autonym is Chatickas-si-Chaticks, meaning "men of men".

Pawnee Confederacy was divided into four nations

Chaui (Tcawi) - generally recognized as being the leading band although each band was autonomous and as was typical of many Indian tribes each band saw to its own although with outside pressures from the Spanish, French and Americans, as well as neighboring tribes saw the Pawnee drawing closer together.

Kitkehahki (Republican)

Pitahauerat (Tappage)

Skidi (Wolf)

The Pawnee were a matriarchal people, descent was reckoned through the mother and a young couple would traditionally move into the bride's parents' lodge. Women were active in political life although men would take decision making responsibilities. This may seem contradictory, but one must consider that tribal groups will allow far more flexibility in political life due to the simple fact that survival of the tribe is paramount, not political might and power. Within the lodge the above-mentioned sections were designated for the three classes of women.

Young single women just learning their responsibilities

Mature women who did much of the labor

Older women who looked after the young children

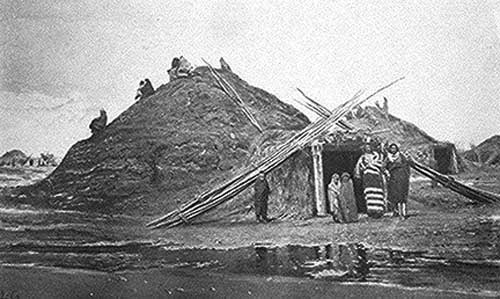

The Pawnee lodges tended to be oval in shape, the frame was constructed of 10-15 posts set some ten feet apart which formed the floor of the lodge. In the centre were four posts representing the four directions, this framework was then covered with willow branches, grass and earth. A hole was left in the centre which served as a combined chimney and skylight, the lodge itself was semi subterranean and the floor was approximately three feet below ground level.

A buffalo skin door on a hinge could be closed at night and wedged shut. There could be as many as 30-50 people living in each lodge. A village could consist of as many as 300-500 people and 10-15 households. Each lodge was divided in two, north and south and each section had a head who oversaw the daily business, each section was further subdivided into three. The membership of the lodge was actually quite flexible. Twice a year the tribe went on a buffalo hunt and on their return the inhabitants of the lodges would often move into another lodge, although they generally remained within the village.

The Pawnee had a sedentary lifestyle combining village life and seasonal hunting, which had long been established on the Plains. Archeology studies of ancient sites have demonstrated the people lived in this pattern for nearly 700 years, since about 1250 CE.

They generally settled close to the rivers and placed their lodges on the higher banks. They built earth lodges that by historical times tended to be oval in shape; at earlier stages, they were rectangular. They constructed the frame, made of 10-15 posts set some ten feet apart, which outlined the central room of the lodge. Lodge size varied based on the number of poles placed in the center of the structure. Most lodges had 4, 8 or 12 center poles. A common feature in Pawnee lodges were four painted poles, which represented the four cardinal directions and the four major star gods (not to be confused with the Creator.) A second outer ring of poles outlined the outer circumference of the lodge. Horizontal beams linked the posts together.

The frame was covered first with smaller poles, tied with willow withes. The structure was covered with thatch, then earth. A hole left in the center of the covering served as a combined chimney/smoke hole and skylight. The door of each lodge was placed to the east and the rising sun. A long, low passageway, which helped keep out outside weather, led to an entry room that had an interior buffalo-skin door on a hinge. It could be closed at night and wedged shut. Opposite the door, on the west side of the central room, a buffalo skull with horns was displayed. This was considered great medicine.

Mats were hung on the perimeter of the main room to shield small rooms in the outer ring, which served as sleeping and private spaces. The lodge was semi-subterranean, as the Pawnee recessed the base by digging it approximately three feet below ground level. This insulated the interior from extreme temperatures. Lodges were strong enough to support adults, who routinely sat on them, and the children who played on the top of the structures.

As many as 30-50 people might live in each lodge, and they were usually of related families. A village could consist of as many as 300-500 people and 10-15 households. Each lodge was divided in two (the north and south), and each section had a head who oversaw the daily business. Each section was further subdivided into three duplicate areas, with tasks and responsibilities related to the age of women and girls, as described below. The membership of the lodge was quite flexible.

The tribe went on buffalo hunts in summer and winter. Upon their return, the inhabitants of a lodge would often move into another lodge, although they generally remained within the village. Men's lives were more transient than those of women. They had obligations of support for the wife (and family they married into), but could always go back to their mother and sisters for a night or two of attention. When young couples married, they lived with the woman's family.

The Pawnee women were "skilled horticulturalists" and cooks, cultivating and processing ten varieties of corn, seven of pumpkins and squashes, and eight of beans. They planted their crops along the fertile river bottomlands. These crops provided a wide variety of nutrients and complemented each other in making whole proteins. In addition to varieties of flint corn and flour corn for consumption, the women planted an archaic breed which they called "Wonderful" or "Holy Corn", specifically to be included in the sacred bundles.

The holy corn was cultivated and harvested to replace corn in the winter and summer sacred bundles. Seeds were taken from sacred bundles for the spring planting ritual. The cycle of corn determined the annual agricultural cycle, as it was the first to be planted and first to be harvested (with accompanying ceremonies involving priests and men of the tribe as well.)

In keeping with their cosmology, the Pawnee classified the varieties of corn by color: black, spotted, white, yellow and red (which, excluding spotted, related to the colors associated with the four semi-cardinal directions). The women kept the different strains pure as they cultivated the corn. While important in agriculture, squash and beans were not given the same theological meaning as corn.

After they obtained horses, the Pawnee adapted their culture and expanded their buffalo hunting seasons. With horses providing a greater range, the people traveled in both summer and winter westward to the Great Plains for buffalo hunting. They often traveled 500 miles or more in a season. In summer the march began at dawn or before, but usually did not last the entire day.

Once buffalo were located, hunting did not begin until the medicine men of the tribe considered the time propitious. Then the hunt began by the men advancing together toward the buffalo, but no one could kill any buffalo until the warriors of the tribe gave the signal. Anyone who broke ranks was severely beaten.

During the chase, the hunters guided their ponies with their knees and wielded bows and arrows. They could incapacitate buffalo with a single arrow shot into the flank between the lower ribs and the hip. The animal would soon lie down and perhaps bleed out, or the hunters would finish it off. An individual hunter might shoot as many as five buffalo in this way before backtracking and finishing them off. They preferred to kill cows and young bulls, as the taste of older bulls was disagreeable.

After successful kills, the women processed the bison meat and skin: the flesh was sliced into strips and dried on poles over slow fires and stored. Prepared in this way, it was usable for several years. Although the Pawnee preferred buffalo, they also hunted other game, including elk, bear, panther, and skunk, for meat and skins. The skins were used for clothing and accessories, storage bags, foot coverings, fastening ropes and ties, etc.

The people returned to their villages to harvest crops when the corn was ripe in late summer, or in the spring when the grass became green and they could plant a new cycle of crops. Summer hunts extended from late June to about the first of September; but might end early if hunting was successful. Sometimes the hunt was limited to what is now western Nebraska. Winter hunts were from late October until early April and were often to the southwest into what is now western Kansas.

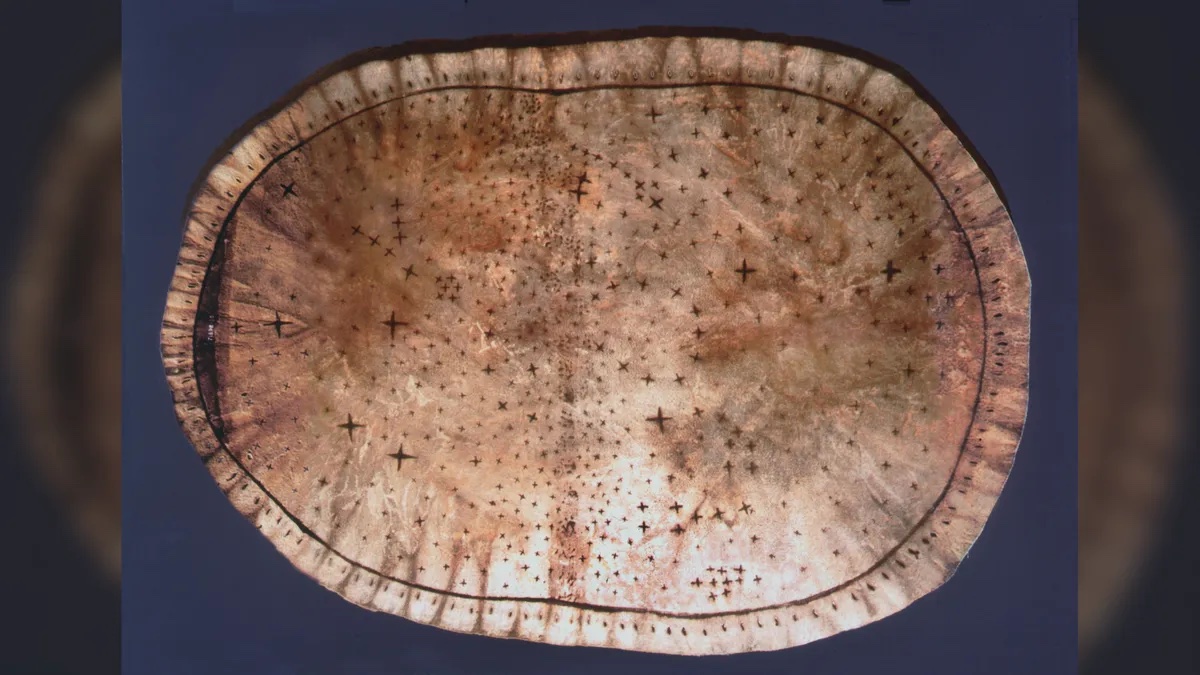

Pawnee Star Chart: A precontact elk-skin map used by Indigenous priests to tell an origin story Live Science - September 14, 2025

The Pawnee Star Chart is a series of crosses sprinkled around an oval piece of elk skin. Likely made in the early 17th century by the Skiri (also called the Skidi) band of the Pawnee Nation, the chart is a fairly accurate representation of the night sky, but the meaning of the chart is still debated.

According to amateur astronomer Ralph Buckstaff, who published a study about the chart in 1927, it was discovered in a sacred bundle in 1902 by Skiri anthropologist James Murie, who passed it on to the Field Museum in Chicago. At the time, the chart was estimated to be at least 300 years old. The piece of tanned elk skin measures roughly 15 by 22 inches (38 by 56 centimeters), and hand-drawn stars cover the surface. Buckstaff interpreted the chart as a depiction of the night sky, separated into two halves by a centerline of very small stars possibly representing the Milky Way.

On the left side, the stars line up into Northern Hemisphere winter constellations, while the right side features summer constellations. This suggested to Buckstaff that the Pawnee recognized the seasonal shift of the stars.

Like many other Native American tribes, the Pawnee had a cosmology with elements of all of nature represented in it. They based many rituals in the four cardinal directions. Medicine men created sacred bundles which included materials, such as an ear of corn, with great symbolic value. These were used in many religious ceremonies to maintain the balance of nature and the Pawnee relationship with the gods and spirits. The Pawnee were not part of the Sun Dance tradition. In the 1890s, the people participated in the Ghost Dance movement.

The Ghost Dance -- also called the Ghost Dance of 1890 -- was a new religious movement which was incorporated into numerous Native American belief systems. The traditional ritual used in the Ghost Dance, the circle dance, has been used by many Native Americans since prehistoric times. In accordance with the prophet Jack Wilson (Wovoka)'s teachings, it was first practiced for the Ghost Dance among the Nevada Paiute in 1889. The practice swept throughout much of the Western United States, quickly reaching areas of California and Oklahoma. As the Ghost Dance spread from its original source, Native American tribes synthesized selective aspects of the ritual with their own beliefs. This process often created change in both the society that integrated it, and in the ritual itself.

The chief figure in the movement was the prophet of peace, Jack Wilson, known as Wovoka among the Paiute. He prophesied a peaceful end to white expansion while preaching goals of clean living, an honest life, and cross-cultural cooperation by Native Americans. Practice of the Ghost Dance movement was believed to have contributed to Lakota resistance. In the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890, U.S. Army forces killed at least 153 Lakota Sioux. The Sioux variation on the Ghost Dance tended towards millenarianism, an innovation that distinguished the Sioux interpretation from Jack Wilson's original teachings. The Caddo Nation still practices the Ghost Dance today.

The Pawnee believed that the Morning Star and Evening Star gave birth to the first Pawnee woman. The first Pawnee man was the offspring of the union of the Moon and the Sun. As they believed they were descendants of the stars, cosmology had a central role in daily and spiritual life. They planted their crops according to the position of the stars, which related to the appropriate time of season for planting. Like many tribal bands, they sacrificed maize and other crops to the stars.

The Pawnee placed great significance on Sacred Bundles, which formed the basis of many religious ceremonies maintaining the balance of nature and the relationship with the gods and spirits. They were part of the Ghost Dance phenomenon of the 1890s.

Sacred Bundles have different levels of power and are used by tribal and village priests, doctors, warriors, and certain families. Only women can own the bundles and only men know and perform ceremonies with them. This bundle is ritually kept and never opened. It is exhibited over the sacred place in the lodge.

They equated the stars with the gods and planted their crops according to the position of the stars. Like many tribal units they sacrificed maize and other crops. There is reference to human sacrifice right up until the mid eighteenth century, Gene Welts in his book The Lost Universe makes note of a young Lakota captive who was tied to a tree and shot with arrows. She was thought to be the last human sacrifice performed by the Pawnee, Welts attributes this peculiarity to their Aztec kin to the south.

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado visited the neighboring Wichita in 1541 where he encountered a Pawnee chief from Harahey, north of Kansas or Nebraska. Nothing much is mentioned of the Pawnee until the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries when successive incursions of Spanish, French and English settlers attempted to enlarge their possessions.

The tribes however tended to make alliances as and when it suited them. An interesting point to note being that different Pawnee subtribes could make treaties with warring European powers without disrupting the underlying unity; the Pawnee were masters at unity within diversity. A tribal delegation visited President Jefferson and in 1806 Lieutenant Zebulon Pike, Major G. C. Sibley, Major S. H. Long, amongst others began visiting the Pawnee villages. Their policy being to befriend and defraud the tribes, part of the Manifest Destiny doctrine that had plagued American society.

The years 1818, 1825, 1833, 1848, 1857, and 1892 are significant years when the Pawnee ceded territory to the Americans and in 1857 they were settled in Nebraska, in 1875 they were finally moved to Indian Territory, Oklahoma, a large territory that had served as a 'dumping ground' for tribes displaced from the east and elsewhere. Many Pawnee men joined the US cavalry as scouts rather than face the ignominy of reservation life and the inevitable loss of their freedom and culture.

In the 20th century Christianity supplanted the older religion. In 1780 the Pawnee are thought to have numbered around 10,000, but by the 19th century, epidemics of smallpox and cholera wiped out most of the Pawnee, reducing the population to approximately 600 by the year 1900; as of 2002, there are approximately 2500 Pawnee.

The Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936 established the Pawnee Business Council, the Nasharo (Chiefs) Council, and a tribal constitution, bylaws, and charter. An out of court settlement in 1964 awarded the Pawnee Nation $7,316,096.55 for undervalued ceded land from the previous century. Bills such as the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 have gone some way to address the mistakes of the past and help the Pawnee Nation regain some of their pride and culture. Today the Pawnee are still celebrating their culture and meet twice a year for the inter-tribal gathering with their kinsmen the Wichita Indians and the four day Pawnee Homecoming for Pawnee veterans in July. Many Pawnee return to their traditional lands to visit relatives, craft shows and take part in powwows.

The Wichita Indians formed a loose confederation on the Southern Plains, including such tribes as Panis Piques, Taovayas, Guichitas, Tawakonis, Kichais, and Wacos, and they lived in fixed villages notable for domed-shaped and grass-covered dwellings. The Wichitas were successful hunters and farmers, skillful traders and negotiators. They ranged as far south as San Antonio, Texas to as far north as Great Bend, Kansas. Their population at the time of first contact with the Europeans is estimated at 200,000. They were discovered by the Spanish conquistador Coronado in 1541 in South Central Kansas but by 1719 had migrated southward to Oklahoma. During the Civil War they moved back to Kansas and established a village at the site of present-day Wichita, Kansas.Their numbers dwindled rapidly upon contact with people of European descent. In 1780, it was estimated that there were about 3,200 total Wichita. By 1868, the population is recorded as being 572 total Wichita. By the time of the census of 1937, there were only 385 Wichita officially left.

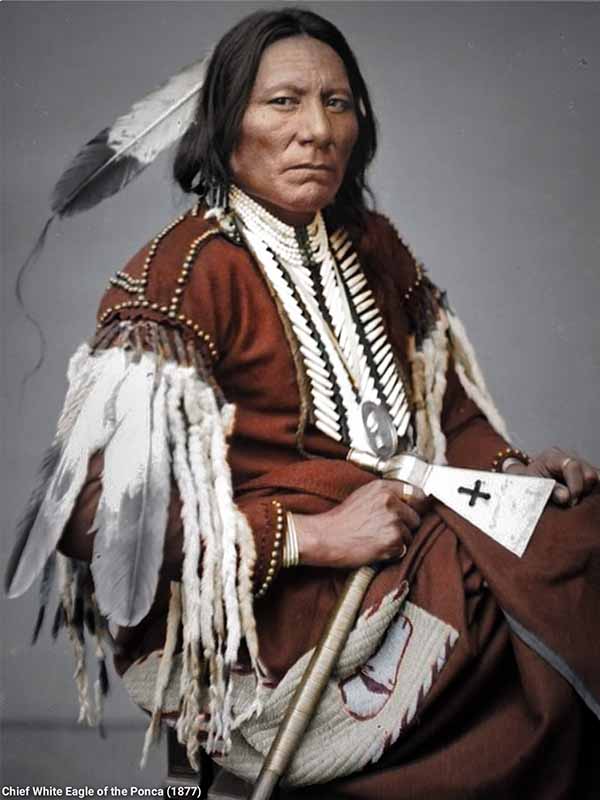

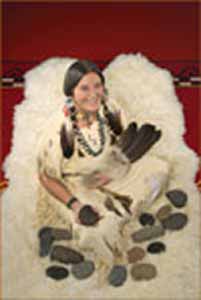

White Bear Medicine Woman