The Ojibwe (also Ojibwa or Ojibway) or Chippewa (also Chippeway) are among the largest groups of Native Americans–First Nations north of Mexico. They are divided between Canada and the United States. In Canada, they are the second-largest population among First Nations, surpassed only by Cree. In the United States, they had the fourth-largest population among Native American tribes, surpassed only by Navajo, Cherokee and the Lakota.

Because many Ojibwe were historically formerly located mainly around the outlet of Lake Superior, which the French colonists called Sault Ste. Marie, they referred to the Ojibwe as Saulteurs. Ojibwe who subsequently moved to the prairie provinces of Canada have retained the name Saulteaux. Ojibwe who were originally located about the Mississagi River and made their way to southern Ontario are known as the Mississaugas.

The Ojibwe peoples are a major component group of the Anishinaabe-speaking peoples, a branch of the Algonquian language family which includes the Algonquin, Nipissing, Oji-Cree, Odawa and the Potawatomi. The Ojibwe peoples number over 56,440 in the U.S., living in an area stretching across the northern tier from Michigan west to Montana.

Another 77,940 of main-line Ojibwe; 76,760 Saulteaux and 8,770 Mississaugas, in 125 bands, live in Canada, stretching from western Quebec to eastern British Columbia. They are historically known for their crafting of birch bark canoes, sacred birch bark scrolls, use of cowrie shells for trading, cultivation of wild rice, and use of copper arrow points. In 1745 they adopted guns from the British to use to defeat and push the Dakota nation of the Sioux to the south.

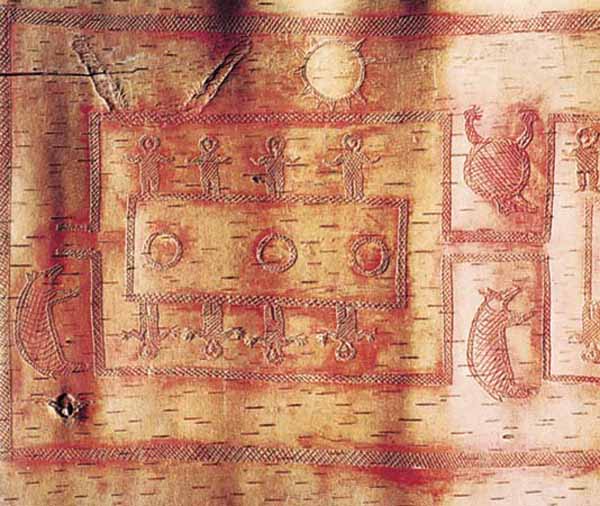

The Ojibwe Nation was the first to set the agenda with European-Canadian leaders for signing more detailed treaties before many European settlers were allowed too far west. The Midewiwin Society is well respected as the keeper of detailed and complex scrolls of events, history, songs, maps, memories, stories, geometry, and mathematics.

The Ojibwe language is known as Anishinaabemowin or Ojibwemowin, and is still widely spoken, but the number of fluent speakers has declined sharply. Today, most of the language's fluent speakers are elders. A movement has picked up in recent years to revitalize the language, and restore its strength as an anchor of Ojibwe culture.

The language belongs to the Algonquian linguistic group, and is descended from Proto-Algonquian. Its sister languages include Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Cree, Fox, Menominee, Potawatomi, and Shawnee. Anishinaabemowin is frequently referred to as a "Central Algonquian" language; however, Central Algonquian is an area grouping rather than a linguistic genetic one. Ojibwemowin is the fourth-most spoken Native language in North America (US and Canada) after Navajo, Cree, and Inuktitut. Many decades of fur trading with the French established the language as one of the key trade languages of the Great Lakes and the northern Great Plains.

The popularity of the epic poem The Song of Hiawatha, written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in 1855, publicized the Ojibwe culture. The epic contains many toponyms that originate from Ojibwe words.

According to their tradition, and from recordings in birch bark scrolls, many Ojibwe came from the eastern areas of North America, which they called Turtle Island, and from along the east coast. Turtle Island is a term used by several Northeastern Woodland Native American tribes, especially the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois Confederacy, for the continent of North America.

The Ojibwe traded widely across the continent for thousands of years and knew of the canoe routes west and a land route to the west coast. The identification of the Ojibwe as a culture or people may have occurred in response to contact with Europeans. The Europeans preferred to deal with bounded groups and tried to identify those they encountered.

According to the oral history, seven great miigis (radiant/iridescent) beings appeared to the peoples in the Waabanakiing (Land of the Dawn, i.e., Eastern Land) to teach them the mide way of life. One of the seven great miigis beings was too spiritually powerful and killed the peoples in the Waabanakiing when they were in its presence. The six great miigis beings remained to teach, while the one returned into the ocean.

The six great miigis beings established doodem (clans) for the peoples in the east, symbolized by animal, fish or bird species. The five original Anishinaabe doodem were the Wawaazisii (Bullhead), Baswenaazhi (Echo-maker, i.e., Crane), Aan'aawenh (Pintail Duck), Nooke (Tender, i.e., Bear) and Moozoonsii (Little Moose), then these six miigis beings returned into the ocean as well. If the seventh miigis being stayed, it would have established the Thunderbird doodem.

At a later time, one of these miigis appeared in a vision to relate a prophecy. It said that if the Anishinaabeg did not move further west, they would not be able to keep their traditional ways alive because of the many new settlements and European immigrants who would arrive soon in the east. Their migration path would be symbolized by a series of smaller Turtle Islands, which was confirmed with miigis shells (i.e., cowry shells). After receiving assurance from the their "Allied Brothers" (i.e., Mi'kmaq) and "Father" (i.e., Abnaki) of their safety to move inland, the Anishinaabeg gradually migrated along the St. Lawrence River to the Ottawa River to Lake Nipissing, and then to the Great Lakes.

Traditionally, the Ojibwe had a patrilineal system, in which children were born to the father's clan. People had to be from different clans to marry. Continuing their westward expansion, the Ojibwe divided into the "northern branch," following the north shore of Lake Superior, and "southern branch," along its south shore. As the peoples continued to migrate westward, the "northern branch" divided into a "westerly group" and a "southerly group".

The "southern branch" and the "southerly group" of the "northern branch" came together at their "sixth stopping place" on Spirit Island located in the St. Louis River estuary of the present-day Duluth/Superior region. The people were directed in a vision by the miigis being to go to the "place where there is food (i.e., wild rice) upon the waters." Their second major settlement, referred as their "seventh stopping place", was at Shaugawaumikong (or Zhaagawaamikong, French, Chequamegon) on the southern shore of Lake Superior, near the present La Pointe, Wisconsin.

The "westerly group" of the "northern branch" migrated along the Rainy River, Red River of the North, and across the northern Great Plains until reaching the Pacific Northwest. Along their migration to the west, they came across many miigis, or cowry shells, as told in the prophecy.

The first historical mention of the Ojibwe occurs in the French Jesuit Relation of 1640, a report by the missionary priests to their superiors in France. Through their friendship with the French traders (coureur des bois and voyageurs), the Ojibwe gained guns, began to use European goods, and began to dominate their traditional enemies, the Lakota and Fox to their west and south. They drove the Sioux from the Upper Mississippi region to the area of the present-day Dakotas, and forced the Fox down from northern Wisconsin. The latter allied with the Sauk for protection.

By the end of the 18th century, the Ojibwe controlled nearly all of present-day Michigan, northern Wisconsin, and Minnesota, including most of the Red River area. They also controlled the entire northern shores of lakes Huron and Superior on the Canadian side and extending westward to the Turtle Mountains of North Dakota. In the latter area, the French Canadians called them Ojibwe or Saulteaux.

The Ojibwe (Chippewa) were part of a long-term alliance with the Anishinaabe Ottawa and Potawatomi peoples, called the Council of Three Fires. They fought against the Iroquois Confederacy, based mainly to the southeast of the Great Lakes in present-day New York, and the Sioux. The Ojibwe expanded eastward, taking over the lands along the eastern shores of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay. In part due to its long trading alliance, the Ojibwe allied with the French against Great Britain and its colonists in the Seven Years' War (also called the French and Indian War).

After losing the war, in 1763 France was forced to cede "its" colonial claims to lands in Canada and east of the Mississippi River to Britain. After adjusting to British colonial rule, the Ojibwe allied with them and against the United States in the War of 1812. They had hoped a British victory could protect against United States settlers' encroachment on their territory.

Following the war, the United States government tried to forcibly remove all the Ojibwe to Minnesota west of Mississippi River. The Ojibwe resisted, and there were violent confrontations. In the Sandy Lake Tragedy, the US killed several hundred Ojibwe. Through the efforts of Chief Buffalo and the rise of popular opinion in the US against Ojibwe removal, the bands east of the Mississippi were allowed to return to reservations on ceded territory. A few families were removed to Kansas as part of the Potawatomi removal.

In British North America, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 following the Seven Years' War governed the cession of land by treaty or purchase . Subsequently France ceded most of the land in Upper Canada to Great Britain. Even with the Jay Treaty signed between the Great Britain and the United States, the newly formed United States did not fully uphold the treaty. Illegal United States immigration into Ojibwe and other Native American lands continued, and the tribes retaliated in the series of battles called the Northwest Indian War. As it was still preoccupied by war with France, Great Britain ceded to the United States much of the lands in Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, parts of Illinois and Wisconsin, and northern Minnesota and North Dakota to settle the boundary of their holdings in Canada.

Many of the land cession treaties the British made with the Ojibwe provided for their rights for continued hunting, fishing and gathering of natural resources after land sales. The government signed numbered treaties in northwestern Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. British Columbia had no signed treaties until the late 20th century, and most areas have no treaties yet.

The government and First Nations are continuing to negotiate treaty land entitlements and settlements. The treaties are constantly being reinterpreted by the courts because many of them are vague and difficult to apply in modern times. The numbered treaties were some of the most detailed treaties signed for their time. The Ojibwe Nation set the agenda and negotiated the first numbered treaties before they would allow safe passage of many more British settlers to the prairies.

Often, earlier treaties were known as "Peace and Friendship Treaties" to establish community bonds between the Ojibwe and the European settlers. These earlier treaties established the groundwork for cooperative resource-sharing between the Ojibwe and the settlers. The United States and Canada viewed later treaties offering land cessions as offering territorial advantages. The Ojibwe did not understand the land cession terms in the same way because of the cultural differences in understanding the uses of land. The governments of the US and Canada considered land a commodity of value that could be freely bought, owned and sold.

The Ojibwe believed it was a fully shared resource, along with air, water and sunlight. At the time of the treaty councils, they could not conceive of separate land sales or exclusive ownership of land. Consequently, today in both Canada and the US, legal arguments in treaty-rights and treaty interpretations often bring to light the differences in cultural understanding of treaty terms to come to legal understanding of the treaty obligations.

During its Indian Removal of the 1830s, US government attempted to relocate tribes from the east to the west of the Mississippi River as the white pioneers increasingly migrated west. By the late 19th century, the government policy was to move tribes onto reservations within their territories. The government attempted to do this to the Anishinaabe in the Keweenaw Peninsula in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

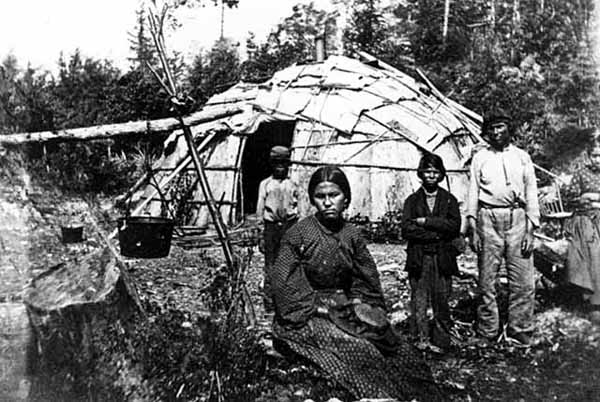

The Ojibwe live in groups (otherwise known as "bands"). Most Ojibwe, except for the Great Plains bands, lived a sedentary lifestyle, engaging in fishing and hunting to supplement the women's cultivation of numerous varieties of maize and squash, and the harvesting of manoomin (wild rice). Their typical dwelling was the wiigiwaam (wigwam), built either as a waginogaan (domed-lodge) or as a nasawa'ogaan (pointed-lodge), made of birch bark, juniper bark and willow saplings.

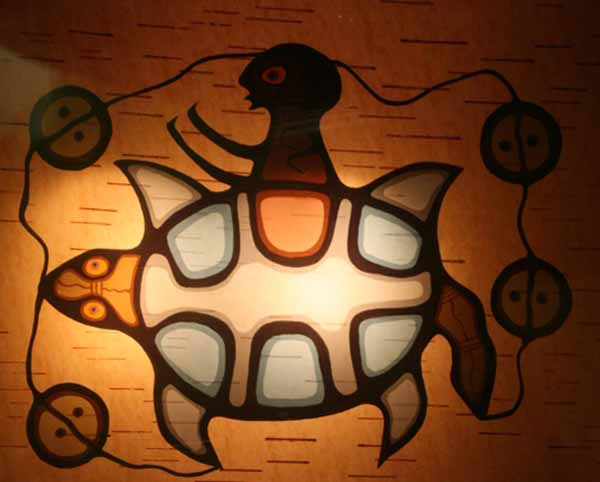

The Ojibwe developed a form of pictorial writing, used in religious rites of the Midewiwin and recorded on birch bark scrolls and possibly on rock. The many complex pictures on the sacred scrolls communicate much historical, geometrical, and mathematical knowledge. Ceremonies also used the miigis shell (cowry shell), which is found naturally in distant coastal areas.

Their use of such shells demonstrates there was a vast trade network across the continent at some time. The use and trade of copper across the continent has also been proof of a large trading network that took place for thousands of years, as far back as the Hopewell tradition. Certain types of rock used for spear and arrow heads were also traded over large distances.

The use of petroforms, petroglyphs, and pictographs was common throughout the Ojibwe traditional territories. Petroforms and medicine wheels were a way to teach the important concepts of four directions and astronomical observations about the seasons, and to use as a memorizing tool for certain stories and beliefs.

During the summer months, the people attend jiingotamog for the spiritual and niimi'idimaa for a social gathering (pow-wows or "pau waus") at various reservations in the Anishinaabe-Aki (Anishinaabe Country). Many people still follow the traditional ways of harvesting wild rice, picking berries, hunting, making medicines, and making maple sugar. Many of the Ojibwe take part in sun dance ceremonies across the continent. The sacred scrolls are kept hidden away until those who are worthy and respect them are given permission to see and interpret them properly.

The Ojibwe would bury their dead in a burial mound. Many erect a jiibegamig or a "spirit-house" over each mound. A traditional burial mound would typically have a wooden marker, inscribed with the deceased's doodem (clan sign). Because of the distinct features of these burials, Ojibwe graves have been often looted by grave robbers. In the United States, many Ojibwe communities safe-guard their burial mounds through the enforcement of the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

The Ojibwe viewed the world in two genders: animate and inanimate, rather than male and female. As an animate, a person could serve the society as a male-role or a female-role. John Tanner and the anthropologist Hermann Baumann have documented that Ojibwe peoples do not live according to the European ideas of gender and its roles. Individuals known as egwakwe (or Anglicised to "agokwa"), contribute in ways that cross European gender lines. Though these egwakweg may contribute to their communities in whatever way brings out their best character, these documented male-to-female transsexual midew among the Ojibwe were more readily noticed by the ethnic European documenters. A well-known egwakwe warrior and guide in Minnesota history was Ozaawindib.

Several Ojibwe bands in the United States cooperate in the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission, which manages the treaty hunting and fishing rights in the Lake Superior-Lake Michigan areas. The commission follows the directives of U.S. agencies to run several wilderness areas. Some Minnesota Ojibwe tribal councils cooperate in the 1854 Treaty Authority, which manages their treaty hunting and fishing rights in the Arrowhead Region. In Michigan, the Chippewa-Ottawa Resource Authority manages the hunting, fishing and gathering rights about Sault Ste. Marie, and the resources of the waters of lakes Michigan and Huron. In Canada, the Grand Council of Treaty #3 manages the Treaty 3 hunting and fishing rights related to the area around Lake of the Woods.

Ojibwe understanding of kinship is complex, and includes not only the immediate family but also the extended family. It is considered a modified bifurcate merging kinship system. As with any bifurcate-merging kinship system, siblings generally share the same kinship term term with parallel cousins, because they are all part of the same clan. The modified system allows for younger siblings to share the same kinship term with younger cross-cousins. Complexity wanes further from the speaker's immediate generation, but some complexity is retained with female relatives. For example, ninooshenh is "my mother's sister" or "my father's sister-in-law" i.e., my parallel-aunt, but also "my parent's female cross-cousin".

Great-grandparents and older generations, as well as great-grandchildren and younger generations, are collectively called aanikoobijigan. This system of kinship speaks of the nature of the Anishinaabe's philosophy and lifestyle, that is, of interconnectedness and balance among all living generations, as well as of all generations of the past and of the future.

The Ojibwe people were divided into a number of odoodeman (clans; singular: doodem) named primarily for animals and birds totems (pronounced doodem). The five original totems were Wawaazisii (Bullhead), Baswenaazhi ("Echo-maker", i.e., Crane), Aan'aawenh (Pintail Duck), Nooke ("Tender", i.e., Bear) and Moozwaanowe ("Little" Moose-tail). The Crane totem was the most vocal among the Ojibwe, and the Bear was the largest - so large, in fact, that it was sub-divided into body parts such as the head, the ribs and the feet.

Traditionally, each band had a self-regulating council consisting of leaders of the communities' clans, or odoodemaan. The band was often identified by the principal doodem. In meeting others, the traditional greeting among the Ojibwe peoples is, "What is your 'doodem'?" ("Aaniin gidoodem?" or "Awanen gidoodem?") to establish social conduct by identifying each of the parties as family, friends or enemies. Today, the greeting has been shortened to "Aaniin."

The Ojibwe people and culture are alive and growing today. During the summer months, the people attend pow-wows or "pau waus" at various reservations in the US and reserves in Canada. Many people still follow the traditional ways of harvesting wild rice, picking berries, hunting and making maple sugar.

The Chippewa, are an important group of Native Americans/First Nations about equally divided between the United States and Canada. The popular name is a corruption of Ojibwa, but they call themselves Anishinabek, or original men, and because they formerly had their main residence at Sault Sainte Marie, at the outlet of Lake Superior, the French knew them by the name of Saulteurs.

They belong to the great Algonquian stock and are related to the Ottawa and Cree. According to their own tradition, they came from the east, advancing along the Great Lakes, and had their first settlement in their present country at Sault Sainte Marie and Shaugawaumikong (French Chegoimegon) on the southern shore of Lake Superior, near the present Lapointe or Bayfield, Wisconsin.

The decline of the fur trade transformed the traditional Ojibwe society. When the British ousted the French from the region, the Ojibwe allied with British traders and soldiers to drive away American settlers. After the US took control of the region, however, the Ojibwe fell on hard economic times. The men took menial jobs in the timber industry, and the role of women weakened. Nevertheless, the bands' isolation enabled the Ojibwe to preserve much of their religion and cultural traditions through the 19th and into the 20th century.

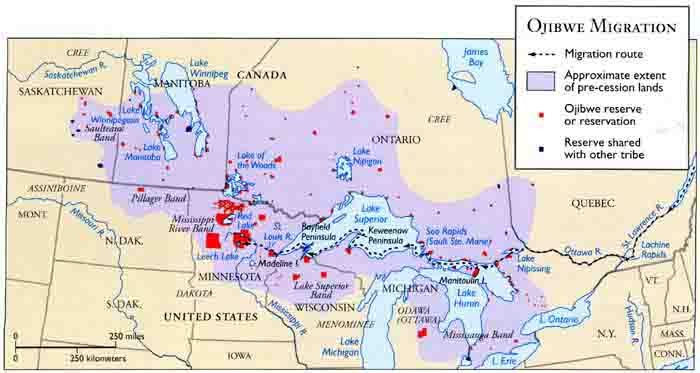

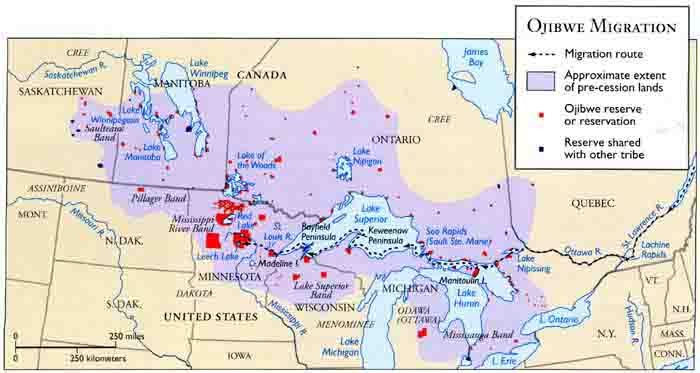

Starting about 1640, many Ojibwe moved (or were driven) westward from the Sault Ste. Marie area. Some turned south into the Lower Peninsula, later joining the Odawa (Ottawa) and Potawatomi in the Three Fires (three brothers) Society. Others continued west along the Lake Superior shore and settled on Madeline Island (in Lake Superior) about 1680. The map below shows not only where the Ojibwe peoples lived prior to European settlement, but also where they migrated to and where they eventually settled (on reservations).

Their first historical mention occurs in the Jesuit Relation of 1640. Through their friendship with the French traders they were able to obtain guns and thus successfully end their hereditary wars with the Sioux and Foxes on their west and south, with the result that the Sioux were driven out from the Upper Mississippi region, and the Foxes forced down from northern Wisconsin and compelled to ally with the Sauk.

By the end of the eighteenth century the Chippewa were the nearly unchallenged owners of almost all of present-day Michigan, northern Wisconsin, and Minnesota, including most of the Red River area and extending westward to the Turtle Mountains of North Dakota, together with the entire northern shores of Lakes Huron and Superior on the Canadian side.

They were never removed as so many other tribes have been, but by successive treaty sales they are now restricted to reservations within this territory, with the exception of a few families living in Kansas.

The Ojibwe have a number of spiritual beliefs passed down by oral tradition under the Midewiwin teachings. These include a creation story and a recounting of the origins of ceremonies and rituals. Spiritual beliefs and rituals were very important to the Ojibwe because spirits guided them through life. Birch bark scrolls and petroforms were used to pass along knowledge and information, as well as for ceremonies. Pictographs were also used for ceremonies.

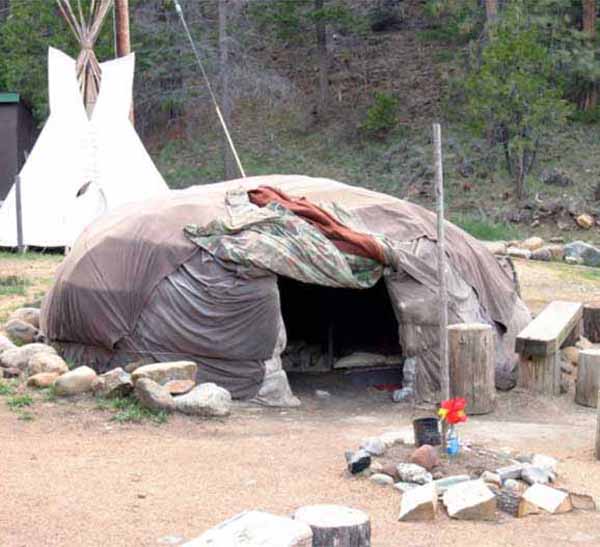

The sweatlodge is still used during important ceremonies about the four directions, when oral history is recounted. Teaching lodges are common today to teach the next generations about the language and ancient ways of the past. The traditional ways, ideas, and teachings are preserved and practiced in such living ceremonies. The Ojbwe crafted the dreamcatcher. They believe that if one is hung above the head of a sleeper, it will catch and trap bad dreams, preventing them from reaching the dreamer. Traditional Ojibwe use dreamcatchers only for children, as they believe that adults should be able to interpret their dreams, good or bad and use them in their lives.

The Chippewas, like all other Indians, were extremely superstitious; indeed, they appeared to be more marked in this peculiarity than were most of the other tribes. It has already been mentioned that the ancestors of the later Saginaw Chippewas imagined that the country which they had wrested from the conquered Sauks was haunted by the spirits of those whom they had slain, and that it was only after the lapse of years that their terrors became allayed sufficiently to permit them to occupy the "haunted hunting-grounds." But the superstition still remained, and, in fact, it was never entirely dispelled.

Long after the valleys of the Saginaw, the Shiawassee, and the Maple became studded with white settlements, the Indians still believed that mysterious Sauks were lingering in the forests and along the margins of their streams for purposes of vengeance. So great was their dread that when (as was frequently the case) they became possessed of the idea that the munesous were in their immediate vicinity, they would fly, as if for their lives, abandoning everything, - wigwams, fish, game, and peltry, - and no amount of ridicule from the whites could induce them to stay and face the imaginary danger.

"Sometimes, during sugar-making," said Mr. Truman B. Fox, of Saginaw, "they would be seized with a sudden panic, and leave everything, - their kettles of sap boiling, their mokoks of sugar standing in their camps, and their ponies tethered in the woods, - and flee helter-skelter to their canoes, as though pursued by the Evil One.

In answer to the question asked in regard to the cause of their panic, the invariable answer was a shake of the head, and a mournful 'an-do-gwane' (don't know)." Some of the northern Indian bands, whose country joined that of the Saginaw Chippewas, played upon their weak superstition, and derived profit from it by lurking around their villages or camps, frightening them into flight, and then appropriating the property which they had abandoned.

A few shreds of wool from their blankets left sticking on thorns or dead brushwood, hideous figures drawn with coal upon the trunks of trees, or marked on the ground in the vicinity of their lodges, was sure to produce this result, by indicating the presence of the dreaded munesous. Often the Indians would become impressed with the idea that these bad spirits had bewitched their firearms, so that they could kill no game.

A very singular superstitious rite was performed annually by the Shiawassee Indians at a place called Pindatongoing (meaning the place where the spirit of sound or echo lives), about two miles above Newburg, on the Shiawassee River, where the stream was deep and eddying.

Chippewa mythology is known from oral legends such as the aadizokaanan (traditional stories, singular aadizokaan), which are told only in winter in order to preserve their transformative powers. The Mideg (singular Mide) are the spiritual leaders of the tribe. A particularly well-respected male spiritual leader was called Jaasakiid. Nanabozho (also known as Nanabush, Wenabozho or Nenabozho) is the trickster and culture hero, who sometimes takes the form of a hare. Aniwye is a skunk spirit and was involved in the creation of skunks.

The windigo is the winter cannibal monster. If someone consumes human flesh, they are said to become possessed by the spirit of the wiindigoo.Baykok is an evil flying skeleton. He is a skeleton because he has starved himself out of obstinance. Wemicus is a trickster god. Ojibwa People

Ojibwa Prophecies