The First Dynasty of ancient Egypt is often combined with the Second Dynasty under the group title, Early Dynastic Period of Egypt. At that time the capital was Thinis.

Information about this dynasty is derived from a few monuments and other objects bearing royal names, the most important being the Narmer palette and macehead as well as Den and Qa'a king lists. No detailed records of the first two dynasties have survived, except for the terse lists on the Palermo stone. The hieroglyphs were fully developed by then, and their shapes would be used with little change for more than three thousand years.

Large tombs of pharaohs at Abydos and Naqada, in addition to cemeteries at Saqqara and Helwan near Memphis, reveal structures built largely of wood and mud bricks, with some small use of stone for walls and floors. Stone was used in quantity for the manufacture of ornaments, vessels, and occasionally, for statues. Tamarix - tamarisk, salt cedar was used to build boats such as the Abydos Boats.

One of the most important indigenous woodworking techniques was the fixed Mortise and tenon joint. A fixed tenon was made by shaping the end of one timber to fit into a mortise (hole) that is cut into a second timber. A variation of this joint using a free tenon eventually became one of the most important features in Mediterranean and Egyptian shipbuilding. I creates a union between two planks or other components by inserting a separate tenon into a cavity (mortise) of the corresponding size cut into each component."

Human sacrifice was practiced as part of the funerary rituals associated with all of the pharaohs of the first dynasty. It is clearly demonstrated as existing during this dynasty by retainers being buried near each pharaoh's tomb as well as animals sacrificed for the burial. The tomb of Djer is associated with the burials of 338 individuals. The people and animals sacrificed, such as donkeys, were expected to assist the pharaoh in the afterlife. For unknown reasons, this practice ended with the conclusion of the dynasty, with shabtis taking the place of actual people to aid the pharaohs with the work expected of them in the afterlife.

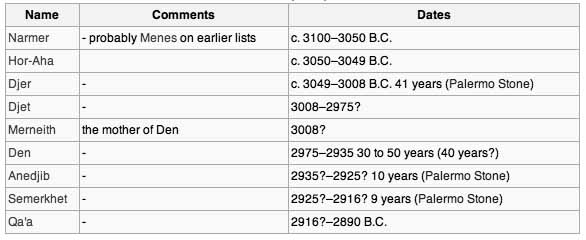

Known rulers in the history of Egypt for the First Dynasty are as follows:

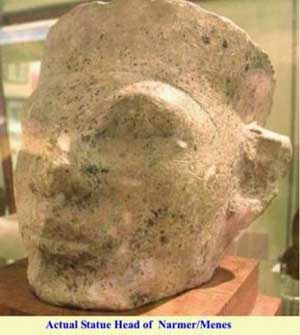

�Narmer (Ancient Egyptian - "Striker") was an Egyptian pharaoh who ruled in the 32nd century BC. Thought to be the successor to the pre-dynastic Serket, he is considered by some to be the founder of the First dynasty. It is thought by many archaeologists that Serket is actually identical with Narmer.

Narmer's name is represented phonetically by the hieroglyphic symbol for a catfish (n'r) and that of a chisel (mr). Other modern variants of his name include "Narmeru" or "Merunar", but convention uses "Narmer". Like other First Dynasty Kings, his name is a single word ("The Striker") and may be shorthand for "Horus is the Striker".

The southern king Narmer (perhaps the legendary Menes) wins a victory over the northern king which is immortalized by Narmer's Palette. The famous Narmer Palette, discovered in 1898 in Hierakonpolis, shows Narmer displaying the insignia of both Upper and Lower Egypt, giving rise to the theory that he unified the two kingdoms. Traditionally, Menes is credited with that unification, and he is listed as being the first pharaoh in Manetho's list of kings, so this find has caused some controversy.

Some Egyptologists hold that Menes and Narmer are in fact the same person; some hold that Menes is the same person with Horus Akha (aka. Hor-Aha) and he inherited an already-unified Egypt from Narmer; others hold that Narmer began the process of unification but either did not succeed or succeeded only partially, leaving it to Menes to complete.

Another equally plausible theory is that Narmer was an immediate successor to the king who did manage to unify Egypt (perhaps the King Scorpion whose name was found on a macehead also discovered in Hierakonpolis), and adopted symbols of unification that had already been in use perhaps for a generation. It should be noted that while there is extensive physical evidence of there being a pharaoh named Narmer, so far there is no evidence other than Manetho's list and from legend for a pharaoh called Menes. The King Lists recently found in Den's and Qa'a's tombs both list Narmer as the founder of their dynasty.

His wife is thought to have been Neithhotep A, a princess of northern Egypt. Inscriptions bearing her name were found in tombs belonging to Narmer's immediate successors Hor-Aha and Djer, implying either that she was the mother or wife of Hor-Aha.

His tomb is thought to have been comprised of two joined chambers (B17 and B18) found in the Umm el-Qa'ab region of Abydos.

During the summer of 1994, excavators from the Nahal Tillah expedition in southern Israel discovered an incised ceramic shard with the serekh sign of Narmer, the same individual whose ceremonial slate palette was found by James E. Quibell in Upper Egypt. The inscription was found on a large circular platform, possibly the foundations of a storage silo on the Halif Terrace. Dated to ca. 3000 BC, mineralogical studies of the shard conclude that it is a fragment of a wine jar which was imported from the Nile valley to Israel some 5000 years ago.

The name Narmer has been found all over Egypt including the local vicinities of Tarkhan to the South of Memphis, the Helwan cemeteries excavated by Zaki Y. Saad, immediately to the East and in the subterranean eastern shaft of Djoser's Step pyramid complex at Saqqara. Obviously he was remembered with some reverence in the area. Perhaps when the earliest site of the Capital is finally located (possibly to the North West) we will be in a much better position to evaluate Narmer's role with Memphis or Inbw hdj as it was then known.

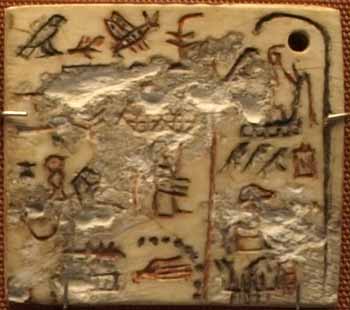

Writing was fairly widespread during this period and although hundred of wooden and ivory labels have been found engraved with hieroglyphs little is known of the individual signs, for example ; the serech of Aha above is thought to feature mud brick paneling (early Palace facade) topped by an unknown structure with a curved roof. From a modern point of view this might seem to refer to the royal aviaries of Aha, where the mace or fighting stick substitutes for a perch and the arched hieroglyph a "pigeon hole" for the Pelegrine falcon to enter.

The arched hieroglyph however is more likely to be derived from the earlier roof shape which makes up the national shrine of lower Egypt which is partly seen on the 'macehead of King Scorpion'. Something quite similar in design to the Aha hieroglyph (a protected enclosure for a female) is also seen on the macehead of Narmer. The shape is also to be seen in the plant like form below.

The ritual mace head of 'Scorpion' is one of the rare artifacts to have survived from this king's reign, and is one of the oldest Egyptian works of art. It is a rounded piece of limestone, shaped like the head of a mace of 25 cm. high. Its dimensions and the fact that it is decorated both show that it was intended as a ritual artifact and not as a real mace head. The mace head was found by archaeologists Quibell and Green during their expedition of 1897/98 in the main deposit at Hierakonpolis. This main deposit also contained other artifacts from the Pre-dynastic and Early Dynastic Periods, among them a long narrow vase also showing the name of king 'Scorpion', as well as, perhaps, the Narmer Palette. It is now on display at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

Note the Scorpion near the King.

No one is quite sure who united Egypt.

Information about the first dynasty is very sketchy.

Was Ancient Egypt's Scorpion King Also China's Yellow Emperor? IFL Science - February 1, 2024

The Yellow Emperor of China and the Scorpion King of Egypt are two elusive figures from the ancient past that inhabit the foggy world between myth and history. Is it possible that they are the same person? It's a sensational theory, but one which a Chinese researcher believes they have proof for.

In a new paper, which is yet to be peer-reviewed, Guang Bao Liu argues that the ruler of Ancient Egypt known as Scorpion I was the figure recorded as the Yellow Emperor in Chinese documents. This is a pretty bold claim since Egyptologists are still determining the true identity of the King Scorpion. Some even dispute his existence. Likewise, historians have debated whether the story of the Yellow Emperor is grounded in reality or mythology.

Menes was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the early dynastic period, credited by classical tradition with having united Upper and Lower Egypt, and as the founder of the first dynasty. The identity of Menes is the subject of ongoing debate, although mainstream Egyptological consensus identifies Menes with the protodynastic pharaoh Narmer (most likely) or first dynasty Hor-Aha. Both pharaohs are credited with the unification of Egypt, to different degrees by various authorities.

The almost complete absence of any mention of Menes in the archaeological record, and the comparative wealth of evidence of Narmer, a protodynastic figure credited by posterity and in the archaeological record with a firm claim to the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, has given rise to a theory identifying Menes with Narmer.

The chief archaeological reference to Menes is an ivory label from Naqada which shows the royal Horus-name Aha (the pharaoh Hor-Aha) next to a building, within which is the royal nebty-name mn, generally taken to be Menes. From this, various theories on the nature of the building (a funerary booth or a shrine), the meaning of the word mn (a name or the verb endures) and the relationship between Hor-Aha and Menes (as one person or as successive pharaohs) have arisen.

Hor-Aha (or Aha or Horus Aha) is considered the second pharaoh of the first dynasty of ancient Egypt in current Egyptology. He lived around the thirty-first century BC. The commonly-used name Hor-Aha is a rendering of the pharaoh's Horus-name, an element of the royal titulary associated with the god Horus, and is more fully given as Horus-Aha meaning Horus the Fighter.

For the Early Dynastic Period, the archaeological record refers to the pharaohs by their Horus-names, while the historical record, as evidenced in the Turin and Abydos king lists, uses an alternative royal titulary, the nebty-name. The different titular elements of a pharaoh's name were often used in isolation, for brevity's sake, although the choice varied according to circumstance and period. Mainstream Egyptological consensus follows the findings of Petrie in reconciling the two records and connects Hor-Aha (archaeological) with the nebty-name Ity (historical).

The same process has led to the identification of the historical Menes (a nebty-name) with the Narmer (a Horus-name) evidenced in the archaeological record (both figures are credited with the unification of Egypt and as the first pharaoh of Dynasty I) as the predecessor of Hor-Aha (the second pharaoh).

There has been some controversy about Hor-Aha. Some believe him to be the same individual as the legendary Menes and that he was the one to unify all of Egypt. Others claim he was the son of Narmer, the pharaoh who unified Egypt. Narmer and Menes may have been one pharaoh, referred to with more than one name. Regardless, considerable historical evidence from the period points to Narmer as the pharaoh who first unified Egypt and to Hor-Aha as his son and heir.

Seals impressions discovered by G. Dreyer in the Umm el-Qa'ab from Merneith and Qa'a burials identify Hor-Aha as the second pharaoh of the first dynasty. His predecessor Narmer had united Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt into a single kingdom. Hor-Aha probably ascended the throne in the late 32nd century BC or early 31st century BC. According to Manetho, he became pharaoh at about the age of thirty and ruled until he was about sixty years old.

Hor-Aha seem to have conducted many religious activities. A visit to a shrine of the goddess Neith is recorded on several tablets from his reign. The sanctuary of Neith he visited was located in the north-east of the Nile Delta at Sai. Furthermore, the first known representation of the sacred Henu-barque of the god Sokar was found engraved on a year tablet dating from his reign.

Vessel inscriptions, labels and sealings from the graves of Hor-Aha and Queen Neithhotep suggest that this queen died during the reign of Aha. He arranged for her burial in a magnificent mastaba excavated by de Morgan . Queen Neithhotep is plausibly Aha's mother . The selection of the cemetery of Naqada as the resting place of Neithhotep is a strong indication that she came from this province. This, in turn, supports the view that Narmer married a member of the ancient royal line of Naqada to strenghten the domination of the Thinite kings over the region.

Most importantly, the oldest mastaba at the North Saqqara necropolis of Memphis, dates to his reign. The mastaba belongs to an elite member of the administration who may have been a relative of Hor-Aha as was customary at the time. This is a strong indication of the growing importance of Memphis during Aha's reign.

Few artifacts remain of Hor-Aha's reign. However, the finely executed copper-axes heads, faience vessel fragments , ivory box and inscribed white marbles all testify to the flourishing of craftsmanship during Aha's time in power.

Inscriptions on ivory tablet from Abydos suggest that Hor-Aha led an expedition against the Nubians. On a year tablet, a year is explicitely called 'Year of smiting of Ta-Sety' (i.e. Nubia). During Hor-Aha's reign, trade with the Southern Levant seem to have been on decline. Contrary to his predecessor Narmer, Hor-Aha's is not yet attested outside of the Nile Valey. This may point to a gradual replacement of long-distance trade between Egypt and its eastern neighbors by a more direct exploitation of the local ressources by the Egyptians. Vessel fragments analysis from an egyptian outpost at En Besor suggests that it was active during Hor-Aha's reign. Other egyptian settlement are know to have been active at the time as well (Byblos and along the Lebanese coast). Finally, Hor-Aha's tomb yielded vessel fragments from the Southern-Levant.

Legend had it that he was carried away by a hippopotamus, the embodiment of the deity Seth. Provided that Hor-Aha was the legendary Menes, another story has it that Hor-Aha was killed by a hippopotamus while hunting.

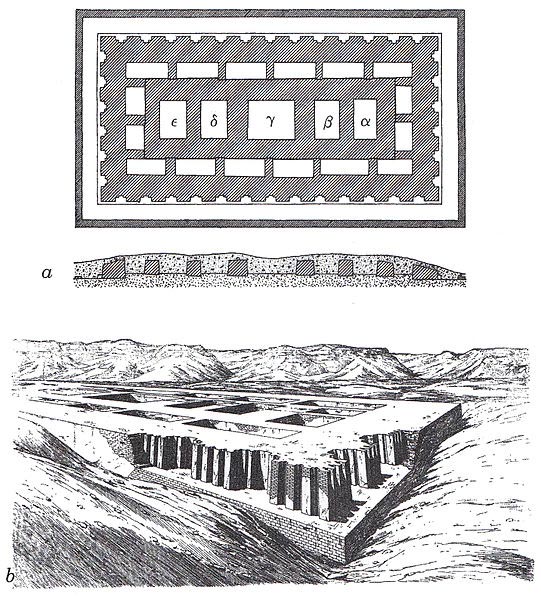

The tomb of Hor-Aha is located in the necropolis of the kings of the 1st Dynasty at Abydos, known as the Umm el-Qa'ab. It comprises three large chambers B10 B15 and B19 which are directly adjacent to Narmer's tomb. The chambers are rectangular, directly dug in the desert floor, their walls lined with mud bricks. The tombs of Narmer and Ka had only two adjacent chambers, while the tomb of Hor-Aha comprises three substantially larger yet separated chambers. The reason for this architecture is that it was difficult at that time to build large ceiling above the chambers. Moreoever timber for these structures often had to be imported from Palestine.

A striking innovation of Hor-Aha's tomb is that members of the royal household were buried with the Pharaoh. It is unclear if they were killed or committed suicide. Among those buried, were servants, dwarfs, women and even dogs. A total of 36 subsidiary burials were laid out in three parallel rows east of Hor-Aha's main chambers. As a symbol of royalty Hor-Aha was even given a group of young lions.

Djer was the second or third pharaoh of the first dynasty of Egypt, which dates from approximately 3100 BC. Uncertainty over the first pharaohs of this dynasty, Menes or Narmer, and Hor-Aha, and possible confusion with the final ruler of the Protodynastic Period, makes the numbering of the First Dynasty problematic. A mummified wrist of Djer or his wife was discovered by Flinders Petrie, but was discarded by Emile Brugsch.

The Abydos King List lists the third pharaoh as Iti, the Turin King List lists a damaged name, beginning with "it" while Egyptian priest Mantheo lists the name Athothis or Athothes.

Reign: His name was found in an inscription on the Wadi Halfa, south of the first Cataract, proving the boundaries of his reign. Hieroglyphs on Ivory and wood labels from Abydos and Saqqara say he reigned for 57 years. Modern research by Toby Wilkinson in Royal Annals of Ancient Egypt stresses that the near-contemporary and therefore, more accurate Palermo Stone ascribes Djer a reign of "41 complete and partial years." Wilkinson notes that Years 1-10 of Djer's reign are preserved in register II of the Palermo Stone, while the middle years of this pharaoh's reign are recorded in register II of Cairo Fragment One.

Military Campaigns: He probably fought several battles against the Libyans in the Nile delta.

Family: Djer was a son of a pharaoh Hor-Aha and his wife Khenthap. His grandfather was probably Narmer, and his grandmother was Neithhotep. Women carrying titles later associated with queens such as great one of the hetes-sceptre and She who sees/carries Horus were buried in subsidiary tombs near the tomb of Djer in Abydos or attested in Saqqara. These women are thought to be the wives of Djer and include:

Herneith, possibly a wife of Djer. Buried in Saqqara.

Seshemetka, buried in Abydos next to the king. She was said to be a wife of Den in Dodson and Hilton.

Penebui, her name and title were found on an ivory label from Saqqara.

Ibsu, known from a label in Saqqara and several stone vessels (reading of name uncertain; name consists of three fish hieroglyphs).

Burial: Like his predecessor, Hor-Aha, he was buried in the holy place Abydos. Close to his grave is another, that probably belongs to his wife Herneith, mother of the later king Den, and possibly his regent during his youth.

The evidence for Djer's life and reign:

Seal prints from graves 2185 and 3471 in Saqqara

Inscriptions in graves 3503, 3506 and 3035 in Saqqara

Seal impression and inscriptions from Helwan (Saad 1947: 165; Saad 1969: 82, pl. 94)

Jar from Turah with the name of Djer (Kaiser 1964: 103, fig.3)

UC 16182 ivory tablet from Abydos, subsidiary tomb 612 of the enclosure of Djer (Petrie 1925: pl. II.8; XII.1)

UC 16172 copper adze with the name of Djer (tomb 461 in Abydos, Petrie 1925: pl. III.1, IV.8)

Inscription of his name (of questioned authenticity, however) at Wadi Halfa, Sudan

Tomb: Similarly to his father Hor-Aha, Djer was buried in Abydos. Djer's tomb is tomb of Petrie. His tomb contains the remains of 300 retainers who were buried with him. Several objects were found in and around the tomb of Djer.

Labels mentioning the name of a palace and the name of Meritneith.

Fragments of two vases inscribed with the name of Queen Neithhotep.

Bracelets of a Queen were found in the wall of the tomb.

In the subsidiary tombs excavators found:

Ivory objects with the name of Neithhotep.

Ivory tablets.

From the 18th Dynasty on, the tomb of Hor-Aha was revered as the tomb of Osiris, and the First Dynasty burial complex, which includes both this and the tomb of Djer, was very important in the Egyptian religious tradition.

Manetho indicates that the First Dynasty ruled from Memphis - and indeed Herneith, one of Djer's wives, was buried nearby at Saqqara. Manetho also claimed that Athothes, who is sometimes identified as Djer, had written a treatise on anatomy that still existed in his own day, over two millennia later.

Similarly to his father Hor-Aha, Djer was buried in Abydos. Djer's tomb is tomb O of Petrie. His tomb contains the remains of 300 retainers who were buried with him. Several objects were found in and around the tomb of Djer. From the 18th Dynasty on, the tomb of Hor-Aha was revered as the tomb of Osiris, and the First Dynasty burial complex, which includes both this and the tomb of Djer, was very important in the Egyptian religious tradition.

Manetho indicates that the First Dynasty ruled from Memphis - and indeed Herneith, one of Djer's wives, was buried nearby at Saqqara. Manetho also claimed that Athothes, who is sometimes identified as Djer, had written a treatise on anatomy that still existed in his own day, over two millennia later.

Djet, also known as Wadj, Zet, and Uadji (in Greek possibly the pharaoh known as Uenephes or possibly Atothis), was the fourth Egyptian pharaoh of the first dynasty. Djet's Horus name means "Horus Cobra" or "Serpent of Horus". Little is known about his reign, but he has become famous because of his tomb stela. It is decorated with Djet's Horus name, and shows that the distinct Egyptian style had already become fully developed.

His stela is displayed at the Louvre in Paris. It is made of limestone carved by the sculptor Serekh. The stela was discovered near the ancient city of Abydos where Wadj's mortuary complex is located. The only other place that Egyptologists found a reference to him was in an inscription near the city of Edfu, to the south of Egypt.

Merneith was a consort and a regent of Ancient Egypt during the first dynasty. She may have been a ruler of Egypt in her own right. The possibility is based on several official records. Her rule occurred the thirtieth century B.C., for an undetermined period. Merneith's name means Beloved by Neith and her stela contains symbols of that deity. She was Djet's senior royal wife and the mother of Den.

Merneith is linked in a variety of seal impressions and inscribed bowls with Djer, Djet and Den. Merneith may have been the daughter of King Djer, but there is no conclusive evidence. As the mother of Den, it is likely that Merneith was the wife of King Djet. No information about the identity of her mother has been found. A clay seal found in the tomb of her son, Den, was engraved with "King's Mother Merneith". It also is known that Den's father was Djet, making it likely, therefore, that Merneith was Djet's royal wife.

Merneith is believed to have become ruler upon the death of her husband, Djet. The title she held, however, is debated. It is possible that her son Den was too young to rule when Djet died, so she may have ruled as regent until Den was old enough to be the king in his own right.

The strongest evidence that Merneith was a ruler of Egypt is her tomb. This tomb in Abydos (Tomb Y) is unique among the otherwise exclusively male tombs. Merneith was buried close to Djet and Den. Her tomb is of the same scale as the tombs of the kings of that period. Two grave stelae were discovered near her tomb. The stelae bear the name Merneith. However, her name is not surrounded by a serekh which was the prerogative of a king. Merneith's name is not included in the King Lists from the New Kingdom. A seal containing a list of pharaohs of the first dynasty was found in the tomb of Qa'a, the third known pharaoh after Den. However, this list does not mention the reign of Merneith.

A few other pieces of evidence exist elsewhere about Merneith:

At Abydos the tomb belonging to Merneith was found in an area associated with other pharaohs of the first dynasty, Umm el-Qa'ab. Two stela made of stone, identifying the tomb as hers, were found at the site.

In 1900 William Petrie discovered Merneith's tomb and, because of its nature, believed it belonged to a previously unknown pharaoh. The tomb was excavated and was shown to contain a large underground chamber, lined with mud bricks, which was surrounded by rows of small satellite burials with at least 40 subsidiary graves.

The servants were thought to assist the ruler in the afterlife. The burial of servants with a ruler was a consistent practice in the tombs of the early first dynasty pharaohs. Large numbers of sacrificial assets were buried in her tomb complex as well, which is another honor afforded to pharaohs that provided the ruler with powerful animals for eternal life. This first dynasty burial complex was very important in the Egyptian religious tradition and its importance grew as the culture endured.

Inside her tomb archaeologists discovered a solar boat that would allow her to travel with the sun deity in the afterlife.

Considered one of the most important archaeological sites of ancient Egypt (near the town of al-Balyana), the sacred city of Abydos was the site of many ancient temples, including Umm el-Qa'ab, the royal necropolis, where early pharaohs were entombed. These tombs began to be seen as extremely significant burials and in later times it became desirable to be buried in the area, leading to the growth of the town's importance as a cult site.

Den, also known as Hor-Den, Dewen and Udimu, is the Horus name of an early Egyptian king who ruled during the 1st dynasty. He is the best archaeologically attested ruler of this period. Den is said to have brought prosperity to his realm and numerous innovations are attributed to his reign.

He was the first to use the title King of Lower- and Upper Egypt, and the first depicted as wearing the double crown (red and white). The floor of his tomb at Umm el-Qa'ab near Abydos is made of red and black granite, the first time in Egypt this hard stone was used as a building material. During his long reign he established many of the patterns of court ritual and royalty used by later rulers and he was held in high regard by his immediate successors.

The Greek historian (priest) Manetho called him "Ousaphaidos" and credited him with a reign of 20 years, whilst the Royal Canon of Turin is damaged and therefore unable to provide information about the duration of Den's reign. Egyptologists and historians generally consider that Den had a reign of 42 years. Their conclusion is based on inscriptions on the Palermo Stone.

Den's serekh name is well attested on earthen seal impressions, on ivory labels and in inscriptions on vessels made of schist, diorite and marble. The artifacts were found at Abydos, Sakkara and Abu Rawash. Den's name is also attested in later documents. For example, the Medical Papyrus of Berlin (ramesside era) discusses several methods of treatment and therapies for a number of different diseases. Some of these methods are said to originate from the reign of Den, but this statement may merely be trying to make the medical advice sound traditional and authoritative. Similarly, Den is mentioned in the "Ani's book of death" (also dated to ramesside times) in chapter 64.

Den's family has been the subject of significant research. His Mother was queen Meritneith; this conclusion is supported by contemporary seal impressions and by the inscription on the Palermo Stone. Den's wives were the queens Semat, Nakht-Neith and -possibly- Qua-Neith. He had also numerous sons and daughters, his possible successors to his heirs could have been king Anedjib and king Semerkhet.

Den's royal court is also well researched. Subsidiary tombs and palatial mastabas at Sakkara belonged to high officials such as Ipka, Ankh-ka, Hemaka, Nebitka, Amka, Iny-ka and Ka-Za. In a subsidiary tomb at Den's necropolis, the rare stela of a dwarf named Ser-Inpu was found.

The birth name of Den was misread in ramesside times. The Royal Table of Abydos has 'Sepatju' written with two symbols for 'district'. This derives from the two desert symbols Den originally had used. The Royal Canon of Turin refers to Qenentj, which is quite difficult to translate. The origin of the hieroglyphs used the Royal Canon of Turin remains unknown. The Royal Saqqara Tablet mysteriously omits Den completely.

According to archaeological records, at the very beginning of his reign, Den had to share the throne with his mother Meritneith for several years. It seems that he was too young to rule himself. Therefore Meritneith reigned as a regent or de facto pharaoh for some time. Such a course of action was not unusual in ancient Egyptian history. Queen Neithhotep may have taken on a similar role before Meritneith, while queens such as Sobekneferu and Hatshepsut were later female Egyptian rulers. Den's mother was rewarded with her own tomb of royal dimensions with her own mortuary cult.

An important innovation during Den's reign was the introduction of numbering using hieroglyphs. Prior to this, important year events were merely depicted in signs and miniatures, sometimes guided by the hieroglyphic sign of a bald palm panicle (renpet), meaning 'year'. From Den's reign onwards, the Egyptians used numbering hieroglyphs for a range of purposes including calculating tax collections and for annotating their year events.

Most religious and political happenings from Den's reign are recorded in the numerous ivory tags and from the Palermo Stone inscription. The tags show important developments in typographics and arts. The surface is artistically parted into sections, each of them showing individual events. For example, one of these tags reports on a epidemic then affecting Egypt. The inscription shows the figure of a shaman with an undefined vessel or urn at his feet. A nearby inscription begins with Henu ... but it is unclear, if that means provision or if it is the first syllable of the name Henu-Ka (a high official).

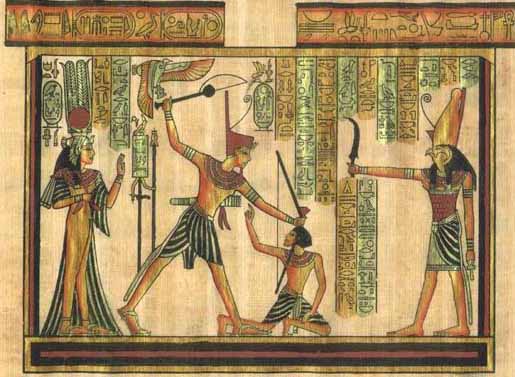

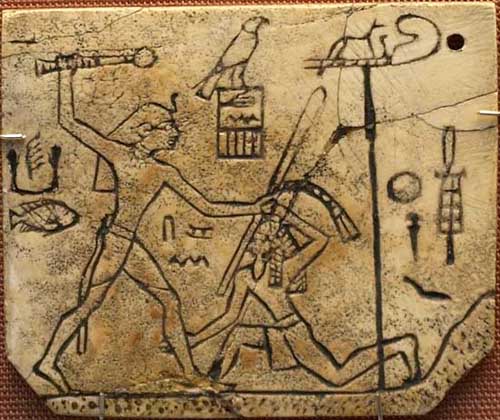

Another tag, known as the MacGregor Label, shows the first complete depiction of an Egyptian king with the so-called Nemes head dress. The picture shows Den in a gesture known as smiting the enemy. In one hand Den holds a smashing sceptre, in the other hand he grabs a foe by his hair. Thanks to the dreadlocks and the conic beard the foe has been identified as of Asian origin. The hieroglyphs at the right side say first smiting of the east. At the left side the name of the high official Iny-Ka is inscribed. It seems that Den sent troops to Sinai and the eastern desert a number of times. Plundering nomads, known by the early Egyptians as Iuntju ('peoples with hunting bows'), were regular foes of Egypt, often causing trouble. They are again mentioned in a rock inscription at Sinai under king Semerkhet, one of Den's successors.

Den was interred within a tomb ("Tomb T") in the Umm el-Qa'ab area of Abydos, which is associated with other first dynasty kings. Tomb T is among the largest and most finely-built of the tombs in this area, and is the first to feature a staircase and a floor made of granite.

His was the first tomb to have a flight of stairs leading to it, those of earlier kings being filled directly above from their roofs. It is possible that the tomb may have used as a storehouse for surplus produce during the king's lifetime, while also making it easier to add grave goods for later use in the afterlife by Den.

Tomb T is also the first tomb to include architectural elements made of stone rather than mud-brick. In the original layout for the tomb, a wooden door was located about half-way up the staircase, and a portcullis placed in front of the burial chamber, designed to keep out tomb robbers. The floor of the tomb was paved in red and black granite from Aswan, the first architectural use of such hard stone on a large scale.

Twenty labels made of ivory and ebony were found in his tomb, 18 of them were found by Flinders Petrie in the spoil heaps left by the less thorough archaeologist Emile Amelineau Among these labels are the earliest known depictions of a pharaoh wearing the double-crown of Egypt (see above), as well as running between ritual stele as part of the Sed festival. Also found are seal impressions that provide the earliest confirmed king list.

Tomb T is surrounded by the burial sites of 136 men and women who were buried at the same time as the king. Thought to be the king's retainers, an examination of some of the skeletons suggests they were strangled, making this an example of human sacrifice which is considered to be common with the pharaohs of this dynasty. This practice which seems to have ceased by the conclusion of the dynasty with shabtis taking the place of the bodies of actual people to aid the pharaohs with the work expected of them in the afterlife

Anedjib, more correctly Adjib and also known as Hor-Anedjib, Hor-Adjib and Enezib, is the Horus name of an early Egyptian king who ruled during the 1st dynasty. The ancient Greek historian Manetho named him "Miebidos" and credited him with a reign of 26 years, while the Royal Canon of Turin credited him with an implausible reign of 74 years. Egyptologists and historians now consider both records to be exaggerations and generally credit Adjib with a reign of 8-10 years.

Adjib is well attested in archaeological records. His name appears in inscriptions on vessels made of schist, alabaster, breccia and marble. His name is also preserved on ivory tags and earthen jar seals. Objects bearing Adjib's name and titles come from Abydos and Sakkara.

Adjib's family has only partially been investigated. His parents are unknown, but it is thought that his predecessor, king Den, may have been his father. Adjib was possibly married to a woman named Betrest. On the Palermo Stone she is described as the mother of Adjib's successor, king Semerkhet. Definite evidence for that view has not yet been found. It would be expected that Adjib had sons and daughters, but their names have not been preserved in the historical record. A candidate for being a possible member of his family line is Semerkhet.

According to archaeological records, Adjib introduced a new royal title which he thought to use as some kind of complement to the Nisut-Bity-title: the Nebuy-title, written with the doubled sign of a falcon on a short standard. It means "The two lords" and refers to the divine state patrons Horus and Seth. It also symbolically points to Lower- and Upper Egypt. Adjib is thought to have legitimatised his role as Egyptian king with the use of this title.

Clay seal impressions record the foundation of the new royal fortress Hor nebw-khet ("Horus, the gold of the divine community") and the royal residence Hor seba-khet ("Horus, the star of the divine community"). Stone vessel inscriptions show that during Adjib's reign an unusually large number of cult statues were made for the king. At least six objects show the depicting of standing statues representing the king with his royal insignia.

Stone vessel inscriptions record that Adjib commemorated a first and even a second Hebsed (a throne jubilee), a feast that was celebrated the first time after 30 years of a king's reign, after that it was repeated every 10th year. But recent investigations suggest that every object showing the Hebsed and Adjib's name together were removed from king Den's tomb.

It would seem that Adjib had simply erased and replaced Den's name with his own. This is seen by egyptologists and historians as evidence that Adjib never celebrated a Hebsed and thus his reign was relatively short. Egyptologists such as Nicolas-Christophe Grimal and Wolfgang Helck assume that Adjib, as Den's son and rightful heir to the throne, may have been quite old when he ascended the Egyptian throne. Helck additionally points to an unusual feature; All Hebsed pictures of Adjib show the notation Qesen ("calamity") written on the stairways of the Hebsed pavilion. Possibly the end of Adjib's reign was a violent one.

Adjib's burial site was excavated at Abydos and is known as "Tomb X". It measures 16.4 x 9.0 metres and is the smallest of all royal tombs in this area. Adjib's tomb has its entrance at the eastern side and a staircase leads down inside. The burial chamber is surrounded by 64 subsidiary tombs and simply divided by a cut-off wall into two rooms. Until the end of the first dynasty, it would seem to have been a tradition that the family and court of the king committed suicide (or were killed) and were then buried along side the ruler in his necropolis.

Semerkhet is the Horus name of an early Egyptian king who ruled during the 1st dynasty. This ruler became known through a tragic legend handed down by ancient Greek historian Manetho, who reported that a calamity of some sort occurred during Semerkhet's reign. The archaeological records seem to support the view that Semerkhet had a difficult time as king and some early archaeologists even questioned the legitimacy of Semerkhet's succession to the Egyptian throne.

Manetho credited him with a reign of 18 years, while the Royal Canon of Turin credited him with an implausibly long reign of 72 years. Egyptologists and historians now consider both statements as exaggerations and credit Semerkhet with a reign of 8 1/2 years. This evaluation is based on the Cairo Stone inscription, where the complete reign of Semerkhet has been recorded. Additionally, they point to the archaeological records, which strengthen the view that Semerkhet had a relatively short reign.

Semerkhet is well attested in archaeological records. His name appears in inscriptions on vessels made of schist, alabaster, breccia and marble. His name is also preserved on ivory tags and earthen jar seals. Objects bearing Semerkhet's name and titles come from Abydos and Sakkara.

Semerkhet's serekh name is commonly translated as "companion of the divine community" or "thoughtful friend". The latter translation is questioned by many scholars, since the hieroglyph khet (Gardiner-sign F32) normally was the symbol for "body" or "divine community".

Semerkhet's birth name is more problematic. Any artefact showing the birth name curiously lacks any artistic detail of the used hieroglyphic sign: a walking man with waving cloak or skirt, a nemes head dress and a long, plain stick in his hands. The reading and meaning of this special sign is disputed.

Egyptologists such as Toby Wilkinson, Bernhard Grdseloff and Jochem Kahl read Iry-Netjer, meaning "He belongs to the gods". This word is often written with single vowels nearby the ideogram of the man. Some ivory tags show the Nebty name written with the single sign of a mouth (Gardiner-sign D21). Therefore they read Semerkhet's throne name as Iry (meaning "one of them/he who belongs to...") and the Nebty name as Iry-Nebty (meaning "He who belongs to the Two Ladies").

This reconstruction is strengthened by the observation that Semerkhet was the first king using the Nebty title in its ultimate form. For unknown reason Semerkhet did not use the Nebuytitle of his predecessor. It seems that he felt connected with the 'Two Ladies', a title referring to the goddesses Nekhbet and Wadjet, both the female equivalents of Horus and Seth. The Nebty title was thought to function as an addition to the Nisut-Bity title.

Scribes and priests of the Ramesside era were also confused, because the archaic ideogram that was used during Semerkhet's lifetime was very similar to the sign of an old man with a walking stick (Gardiner sign A19). This had been read as Semsu or Sem and means "the eldest". It was used as a title identifying someone as the head of the house.

Due to this uncertainty, it seems that the compiler of the Abydos king list simply tried to imitate the original figure, whilst the author of the Royal Canon of Turin seems to have been convinced about reading it as the Gardiner-sign A19 and he wrote Semsem with single vowels. The Royal Table of Sakkara omits Semerkhet's throne name. The reason for that is unknown, but all kings from Narmer up to king Den are also missing their throne names.

Virtually nothing is known about Semerkhet's family. His parents are unknown, but it is thought that one of his predecessors, king Den, might have been his father. Semerkhet was possibly born to queen Betrest. On the Cairo Stone she is described as his mother. Definite evidence for that view has not yet been found. It would be expected that Semerkhet had sons and daughters, but their names have not been preserved in the historical record. A candidate for a possible member of his family line is his immediate successor, king Qa'a.

An old theory, supported by Egyptologists and historians such as Jean-Philippe Lauer, Walter Bryan Emery, Wolfgang Helck and Michael Rice once held that Semerkhet was a usurper and not the rightful heir to the throne. Their assumption was based on the observation that a number of stone vessels with Semerkhet's name on them were originally inscribed with king Adjib's name. Semerkhet simply erased Adjib's name and replaced it with his own. Furthermore they point out that no high official and priest associated with Semerkhet was found at Sakkara. All other kings, such as Den and Adjib, are attested in local mastabas.

Today this theory has little support. Egyptologists such as Toby Wilkinson, I. E. S. Edwards and Winifred Needler deny the 'usurping theory', because Semerkhet's name is mentioned on stone vessel inscriptions along with those of Den, Adjib and Qa'a. The objects were found in the underground galleries beneath the step pyramid of (3rd dynasty) king Djoser at Sakkara.

The inscriptions show that king Qa'a, immediate successor of Semerkhet and sponsor of the vessels, accepted Semerkhet as a rightful ancestor and heir to the throne. Furthermore, the Egyptologists point out that nearly every king of 1st dynasty had the habit of taking special vessels (so-called 'anniversary vessels') from their predecessor's tomb and then replace their predecessor's name with their own.

Semerkhet not only confiscated Adjib's vessels, in his tomb several artifacts from the necropolis of queen Meritneith and king Den were also found. The lack of any high official's tomb at Sakkara might be explained by the rather short reign of Semerkhet. It seems that the only known official of Semerkhet, Henu-Ka, had survived his king: His name appears on ivory tags from Semerkhet's and Qaa's tomb.

Seal impressions from Semerkhet's burial site show the new royal domain Hor wep-khet (meaning "Horus, the judge of the divine community") and the new private household Hut-Ipty (meaning "house of the harem"), which was headed by Semerkhet's wives. Two ivory tags show the yearly 'Escort of Horus', a feast connected to the regular tax collections. Other tags report the cult celebration for the deity of the ancestors, Wer-Wadyt ("the Great White"). And further tags show the celebration of a first (and only) Sokar feast.

While the Cairo Stone reports the whole of Semerkhet's reign, unfortunately, the surface of the stone slab is badly worn and most of the events are now illegible.

Egyptologists and historians pay special attention to the entrance "Destruction of Egypt" in the second window of Semerkhet's year records. The inscription gives no further information about that event. But it has a resemblance to the Manetho's report. The Eusebius version says: His son, Sememspes, who reigned for 18 years; in his reign a very great calamity befell Egypt. The Armenian version sounds similar: Mempsis, annis XVIII. Sub hoc multa prodigia itemque maxima lues acciderunt. ("Mempsis, 18 years. Under him many portents happened and a great pestilence occurred."). Mysteriously none of the documents from after Semerkhet's reign is able to report which kind of "calamity" took place under Semerkhet.

Semerkhet's burial site was excavated in 1899 by archaeologist and Egyptologist Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie at Abydos and is known as "Tomb U". While excavating, Petrie found no stairways like he did at the necropolis of Den and Adjib. He found a ramp, four metres wide and leading straight into the main chamber. The ramp starts around ten metres east outside the tomb and has a base slope of 12° .

Pottery sherd showing Semerkhet's serekh name

The burial chamber measures 29.2 x 20.8 metres and is of simple construction. Petrie found that the king's mastaba once covered the whole of the subsidiary tombs. Now the royal burial formed a unit with the 67 subsidiary tombs. Egyptologists such as Walter Bryan Emery and Toby Wilkinson see this architectural development as proof that the royal family and household were killed willingly when their royal family head had died. Wilkinson goes further and thinks that Semerkhet, as the godlike king, tried to demonstrate his power over the death and life of his servants and family members even in their afterlife. The tradition of burying the family and court of the king when he died was abandoned at the time of king Qaa, one of the last rulers of the 1st dynasty. The tombs of 2nd dynasty founder Hotepsekhemwy onward have no subsidiary tombs.

Most scholars believe that Qa'a was the last king of the 1st dynasty. We may also see his name as Kaa, or several other variations. Though Egyptologists often disagree on dating, our current best guess is that he lived from about 3100 to 2890 BC. According to Manetho he reigned for about 26 years.

Information on Qa'a is limited. He is mentioned on jar sealings and two damaged stela. One one of these stela he is shown wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt and being embraced by the God Horus.

Egyptologists have also discovered the stelae of two of Qa'a's officials, Merka and Sabef. These stelae have more complex inscriptions then earlier hieroglyphics, and may have signaled in increasing sophistication in the use of this writing.

Qa'a had a fairly large tomb in Abydos which measures 98.5 x 75.5 feet or 30 x 23 meters. Manetho gives him a reign of 26 years in his Epitome if this ruler was a certain Biechenes. A long reign is supported by the large size of this ruler's burial site at Abydos. A seal impression bearing Hotepsekhemwy's name was found near the entrance of the tomb of Qa'a (Tomb Q) by the German Archaeological Institute in the mid-1990s. This pharaoh's large Abydos tomb was excavated by German archaeologists in 1993 and proved to contain 26 satellite (i.e. sacrificial) burials. The discovery of the seal impression has been interpreted as evidence that Qa'a was buried, and therefore succeeded, by Hotepsekhemwy, the founder of the second dynasty of Egypt, as Manetho states.

The tomb of one of Qa'a's state officials at Saqqara - a certain noblemen named Merka - contained a stele with many titles. There is a second sed festival attested. This fact plus the high quality of a number of royal steles depicting the king implies that Qa'a's reign was a fairly stable and prosperous period of time. Qa'a's name translates as "His Arm is Raised".

A number of year labels have also been discovered dating to his reign at the First Dynasty burial site of Umm el-Qa'ab in Abydos. Qa'a is believed to have ruled Egypt around 2916 BCE. A dish inscribed with the name and titles of Qa'a was discovered in the tomb of Peribsen (Tomb P of Petrie).

Under Qa'a the officials Merka and Sabef had high positions in the palace administration.

The pharaoh with a bird within his serek is known from only one piece of evidence, and that comes from the galleries under the step pyramid from third dynasty king Djoser at Sakkara.

This object is from a stone vessel made of schist with this king's name carved in.

His position is far from certain, but he is considered to have had a short reign at the end of the second dynasty. This estimation is made by comparing his hieroglyphs' and serek's form to those of other rulers at the time. One of them is a crude serek found in king Qaa's tomb at Abydos in 1902 and possibly showing a bird.

This bird looks like a stork with a long body and neck and a rather short nib, possibly a heron and the picture left shows a similar hieroglyph. His position in the sequence of kings during this rather unknown period is hard to establish with certainty.

He must not be confused with the Horus Ba from the third dynasty whose serek had a human bone, in one occasion together with an ram. (The phonetic sounds in Egyptian is similar in these names).

The reason for placing him after Qaa is mainly the epigraphically similarities (the form of the serek) and a seal from his tomb shows the seven first rulers from the first dynasty in a successive line without mentioning a king called "Bird". Accompanying text from the scanty remains of the Bird Pharaoh is almost identical to some of Qaa's, making it very likely to place him just in this era.