Australopithecus afarensis is a hominid which lived between 3.9 to 3 million years ago belonging to the genus Australopithecus, of which the first skeleton was discovered on November 24, 1974 by Donald Johanson, Yves Coppens and Tim White in the Middle Awash of Ethiopia's Afar Depression.

Donald Johanson, an American anthropologist who is now head of the Institute of Human Origins of Arizona State University, and his team, surveyed Hadar, Ethiopia during the late 1970s for evidence in interpreting Human origins. On November 24, 1974 near the Awash River, Don was planning on updating his field notes but instead one of his students Tom Gray accompanied him to find fossil bones. Both of them were on the hot arid plains surveying on the dusty terrain when a fossil caught both their eyes; arm bone fragments on a slope. As they looked further, more and more bones were found, including a jaw, arm bone, a thighbone, ribs, and vertebrae.

Both Don and Tom had carefully analyzed the partial skeleton and calculated that an amazing 40% of a hominin skeleton was recovered, which, while sounding generally unimpressive, is astounding in the world of anthropology. When fossils are discovered usually only a few fragments are found; rarely are any skulls or ribs intact. The team proceeded to further analysis and Don noticed the feminine stature of the skeleton and argued that it was a female. The skeleton A.L. 444-2 was nicknamed Lucy, after the Beatles song "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds".

Lucy was only 3 feet 8 inches (1.1 m) tall, weighed 29 kilograms (65 lb) and looked somewhat like a Common Chimpanzee, but the observations of her pelvis proved that she had walked upright and more in the manner of humans.

Don Johanson placed Australopithecus afarensis as the last ancestor common to humans and chimpanzees living from 3.9 to 3 million years ago. Although fossils closer to the chimpanzee line have been recovered since the early 1970s, Lucy remains a treasure among anthropologists studying Human origins. The fragmentary nature of the older fossils furthermore deter confident conclusions as to the degree of bipedality or their relation to true hominines.

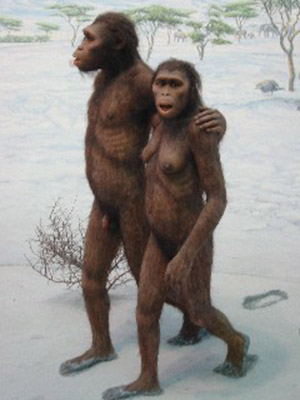

Johanson brought the skeleton back to Cleveland, under agreement with the government of the time in Ethiopia, and returned it according to agreement some 9 years later. Lucy was the first fossil hominin to really capture public notice, becoming almost a household name at the time. Current opinion is that the Lucy skeleton should be classified in the species Australopithecus afarensis. Lucy is preserved at the national Museum in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. A plaster replica is displayed instead of the original skeleton. A diorama of Australopithecus afarensis and other human predecessors showing each species in its habitat and demonstrating the behaviors and capabilities that scientists believe it had is in the Hall of Human Biology and Evolution at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

One of the most striking characteristics about Lucy was that she had a small skull, bipedal knee structure, and molars and front teeth of human (rather than great ape) style and relative size, but a small skull and small body. The image of a bipedal hominid with small skull, but teeth like a human, was quite a revelation to the paleoanthropological world at the time.

This was due to the earlier belief (1950-1970's) that increasing brain size of apes was the trigger for evolving towards humans. Before Lucy, a fossil called '1470' (Homo rudolfensis) with a brain capacity of about 800 cubic centimetres had been discovered, an ape with a bigger brain. If the older theory was correct, humans most likely evolved from the latter. However, it turned out Lucy was the older fossil, yet Lucy was bipedal (walked upright) and had a brain of only around 375 to 500 cc. These facts provided a basis to challenge the older views.

There are differing views on how Lucy or her ancestors first became bipedal full-time.

The so-called 'savanna theory' on how A. afarensis evolved bipedalism hangs on the evidence that around 6 to 8 million years ago there seems to have been a mass extinction of forest dwelling creatures including the oldest hominins recognizable: Sahelanthropus tchadensis and Orrorin tugenensis. This triggered a burst of adaptive radiation, an evolutionary characteristic that generates new species quickly. Lucy's genetic forebears were tree dwelling apes, but in Lucy's world the trees would have been much fewer, and Lucy would have been forced to find a living on the flat savanna. Being bipedal would have had evolutionary advantages. For example, with the eyes higher up, she could see further than quadrupeds. Bipedalism also saves energy. The disadvantages of bipedalism were great - Lucy was the slowest moving primate of her time, for example, but according to the hypothesis, the advantages of bipedalism must have outweighed the disadvantages.

There had previously been problems in the past with designating Australopithecus afarensis as a fully bipedal hominine. In fact these hominines may have occasionally walked upright but still walked on all fours like apes; the curved fingers on A. afarensis are similar to those of modern-day apes, which use them for climbing trees. The phalanges (finger bones) aren't just prone to bend at the joints, but rather the bones themselves are curved. Another aspect of the Australopithecus skeleton that differs from human skeleton is the iliac crest of the pelvic bones. The iliac crest, or hip bone, on a Homo sapiens extends front-to-back, allowing an aligned gait.

A human walks with one foot in front of the other. However, on Australopithecus and on other ape and ape-like species such as the orangutan, the iliac crest extends laterally (out to the side), causing the legs to stick out to the side, not straight forward. This gives a side-to-side rocking motion as the animal walks, not a forward gait.

The so-called aquatic ape theory compares the typical elements of human locomotion (truncal erectness, aligned body, two-leggedness, striding gait, very long legs, valgus knees, plantigrady etc.) with those of chimpanzees and other animals, and proposes that human ancestors evolved from vertical wader-climbers in coastal or swamp forests to shoreline dwellers who collected coconuts, turtles, bird eggs, shellfish etc. by beach-combing, wading and diving. In this view, the australopithecines largely conserved the ancestral vertical wading-climbing locomotion in swamp forests ("gracile" kind, including Australopithecus afarensis and A. africanus) and later more open wetlands ("robust" kind, including Paranthropus boisei and P. robustus). Meanwhile, Plio-Pleistocene Homo had dispersed along the African Rift valley lakes and African and Indian ocean coasts, from where different Homo populations ventured inland along rivers and lakes. However, this theory is not taken seriously by anthropologists.

These hominines were likely to be somewhat like modern Homo sapiens when it came to the matter of social behavior, yet like modern day apes they relied on the safety of trees from predators such as lions.

Australopithecus afarensis fossils have only been discovered within Eastern Africa, which include Ethiopia (Hadar, Aramis), Tanzania (Laetoli) and Kenya (Omo, Turkana, Koobi Fora and Lothagam). A major discovery made by Don Johanson after Lucy's find he discovered the "First Family" including 200 hominid fragments of A. afarensis, discovered near Lucy on the other side of the hill in the Afar region. The site is known as "site 333", by a count of fossil fragments uncovered, such as teeth and pieces of jaw. 13 individuals were uncovered and all were adults, with no injuries caused by carnivores. All 13 individuals seemed to have died at the same time, thus Don concluded that they might have been killed instantly from a flash flood.

Further findings at Afar, including the many hominin bones in site 333, produced more bones of concurrent date, and led to Johanson and White's eventual argument that the Koobi Fora hominins were concurrent with the Afar hominins. In other words, Lucy was not unique in evolving bipedalism and a flat face.

Recently, an entirely new species has been discovered, called Kenyanthropus platyops, however the cranium KNM WT 40000 has a much distorted matrix making it hard to distinguish (however a flat face is present). This had many of the same characteristics as Lucy, but is possibly an entirely different genus.

Another species, called Ardipithecus ramidus, has been found, which was fully bipedal, yet appears to have been contemporaneous with a woodland environment, and, more importantly, contemporaneous with Australopithecus afarensis. Scientists have not yet been able to draw an estimation of the cranial capacity of A. ramidus as only small jaw and leg fragments have been discovered thus far. Read more

'Lucy' Was Neighbors With an Even Older Human Ancestor, Fossils Reveal Science Alert - November 26, 2025

A jumble of bones and teeth confirms two species of human ancestor lived side by side over 3.3 million years ago in Ethiopia's Afar Rift. This is the first clear evidence that these ancient relatives may have overlapped not just in time but also coexisted as neighbors, with remains of each species having been found within 5 kilometers (3 miles) of each other.

Early human ancestor 'Lucy' was a bad runner, and this one tendon could explain why Live Science - December 27, 2024

"Lucy," our 3.2 million-year-old hominin relative, couldn't run very fast, according to a new study. But modeling her running ability has provided new insights into the evolution of human anatomy key to running performance. The human ability to walk and run efficiently on two feet arose around 2 million years ago with our Homo erectus ancestors. But our earlier relatives, the australopithecines, were also bipedal around 4 million years ago. Given the long arms and different body proportions of species like Australopithecus afarensis, though, researchers have assumed that australopithecines were less capable of walking on two legs than modern humans.

Lucy Discovery Is 50: How a Bombshell 1974 Discovery Redefined Human Origins Science Alert - November 27, 2024

She was, for a while, the oldest known member of the human family. Fifty years after the discovery of Lucy in Ethiopia, the remarkable remains continue to yield theories and questions. In a nondescript room in the National Museum of Ethiopia, the 3.18-million-year-old bones are delicately removed from a safe and placed on a long table. They consist of fossilized dental remains, skull fragments, parts of the pelvis and femur that make up the world's most famous Australopithecus afarensis, Lucy. The hominid was discovered on November 24, 1974, in the Afar region of northeast Ethiopia by a team of scientists led by Maurice Taieb, Yves Coppens, Donald Johanson, Jon Kalb, and Raymonde Bonnefille.

Lucy's last day: What the iconic fossil reveals about our ancient ancestor's last hours Live Science - November 20, 2024

Fifty years after a fossil skeleton of Australopithecus afarensis was unearthed in Ethiopia, we know so much more about how this iconic species lived and died.

Ancient human ancestor Lucy was not alone - she lived alongside at least 4 other proto-human species, emerging research suggests Live Science - November 21, 2024

About 3.2 million years ago, our ancestor "Lucy" roamed what is now Ethiopia. The discovery of her fossil skeleton 50 years ago transformed our understanding of human evolution. But it turns out her species, Australopithecus afarensis, wasn't alone. In fact, as many as four other kinds of proto-humans roamed the continent during Lucy's time. But who were Lucy's neighbors, and did they ever interact with her kind?

What the 3.2 million-year-old Lucy fossil reveals about nudity and shame PhysOrg - June 28, 2024

Fifty years ago, scientists discovered a nearly complete fossilized skull and hundreds of pieces of bone of a 3.2-million-year-old female specimen of the genus Australopithecus afarensis, often described as "the mother of us all." During a celebration following her discovery, she was named "Lucy," after the Beatles song "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds."

Lucy had an ape-like brain. Three-million-year-old brain imprints show that Australopithecus afarensis infants may have had a long dependence on caregivers Science Daily - April 3, 2020

A new study led by paleonthropologists reveals that Lucy's species Australopithecus afarensis had an ape-like brain. However, the protracted brain growth suggests that - as is the case in humans -- infants may have had a long dependence on caregivers

'All bets now off' on which ape was humanity's ancestor - Researchers have discovered a nearly complete 3.8-million-year-old skull of an early ape-like human ancestor in Ethiopia. BBC - August 28, 2019

Researchers have discovered a nearly complete 3.8-million-year-old skull of an early ape-like human ancestor in Ethiopia.

An analysis of the new specimen challenges ideas about how the first humans evolved from ape-like ancestors.

The current view that an ape named Lucy was among a species that gave rise to the first early humans may have to be reconsidered.

Early human ancestor Lucy died falling out of a tree BBC - August 29, 2016

New evidence suggests that the famous fossilized human ancestor dubbed "Lucy" by scientists died falling from a great height - probably out of a tree. CT scans have shown injuries to her bones similar to those suffered by modern humans in similar falls. The 3.2 million-year-old hominin was found on a treed flood plain, making a branch her most likely final perch. It bolsters the view that her species - Australopithecus afarensis - spent at least some of its life in the trees.

Cracking the coldest case: How Lucy, the most famous human ancestor, died Science Daily - August 29, 2016

Lucy, the most famous fossil of a human ancestor, probably died after falling from a tree, according to a new study. Lucy, a 3.18-million-year-old specimen of Australopithecus afarensis -- or "southern ape of Afar" -- is among the oldest, most complete skeletons of any adult, erect-walking human ancestor. Since her discovery in the Afar region of Ethiopia in 1974 by Arizona State University anthropologist Donald Johanson and graduate student Tom Gray, Lucy -- a terrestrial biped -- has been at the center of a vigorous debate about whether this ancient species also spent time in the trees.

Lucy had neighbors: A review of African fossils PhysOrg - June 6, 2016

If "Lucy" wasn't alone, who else was in her neighborhood? Key fossil discoveries over the last few decades in Africa indicate that multiple early human ancestor species lived at the same time more than 3 million years ago. A new review of fossil evidence from the last few decades examines four identified hominin species that co-existed between 3.8 and 3.3 million years ago during the middle Pliocene. A team of scientists compiled an overview that outlines a diverse evolutionary past and raises new questions about how ancient species shared the landscape.

'Lucy's baby' found in Ethiopia BBC - September 20, 2006

The 3.3-million-year-old fossilised remains of a human-like child have been unearthed in Ethiopia's Dikika region. The female Australopithecus afarensis bones are from the same species as an adult skeleton found in 1974 which was nicknamed "Lucy". They believe the near-complete remains offer a remarkable opportunity to study growth and development in an important extinct human ancestor. Juvenile Australopithecus afarensis remains are vanishingly rare. The skeleton was first identified in 2000, locked inside a block of sandstone. It has taken five years of painstaking work to free the bones.

Scientists in Ethiopia unearth early skeleton - 4 million years old BBC - March 7, 2005

US and Ethiopian scientists say they have discovered the fossilised remains of one of the earliest human ancestors. The research team, working in the north-east of Ethiopia, believe the remains of the hominid, or primitive human, date back four million years. They say initial study of the bones indicates the creature was bipedal - it walked around on two legs. The fossils were found just 60km (40 miles) from the site where the famous hominid Lucy was discovered. Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis), whose remains were unearthed in 1974, lived 3.2 million years ago and is thought to have given rise to the Homo line that ended in modern humans.

ANCIENT AND LOST CIVILIZATIONS