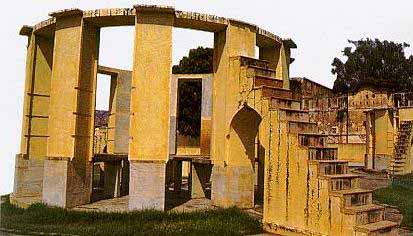

Celestial Observatory

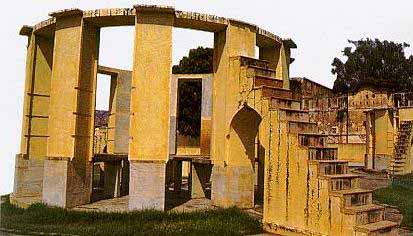

Tool for keeping track of the constellations

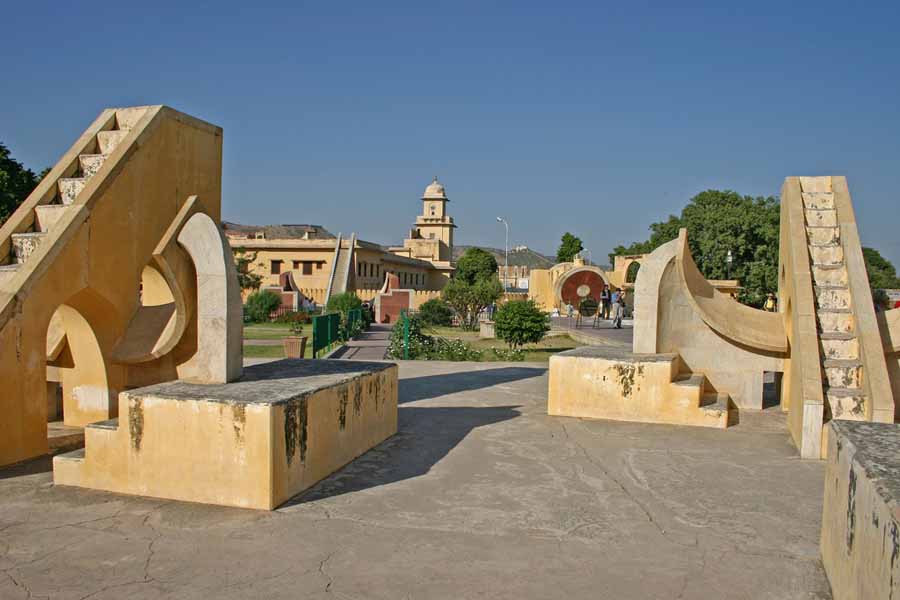

Sun Dial

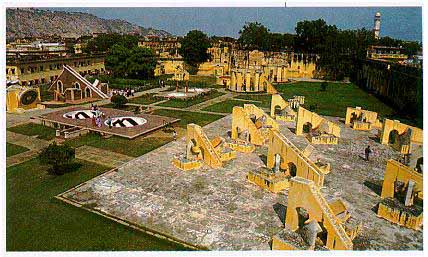

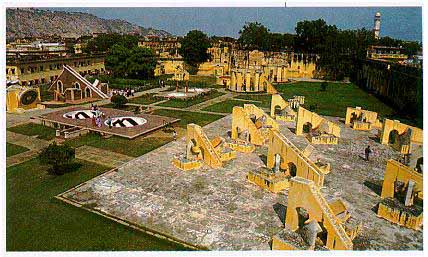

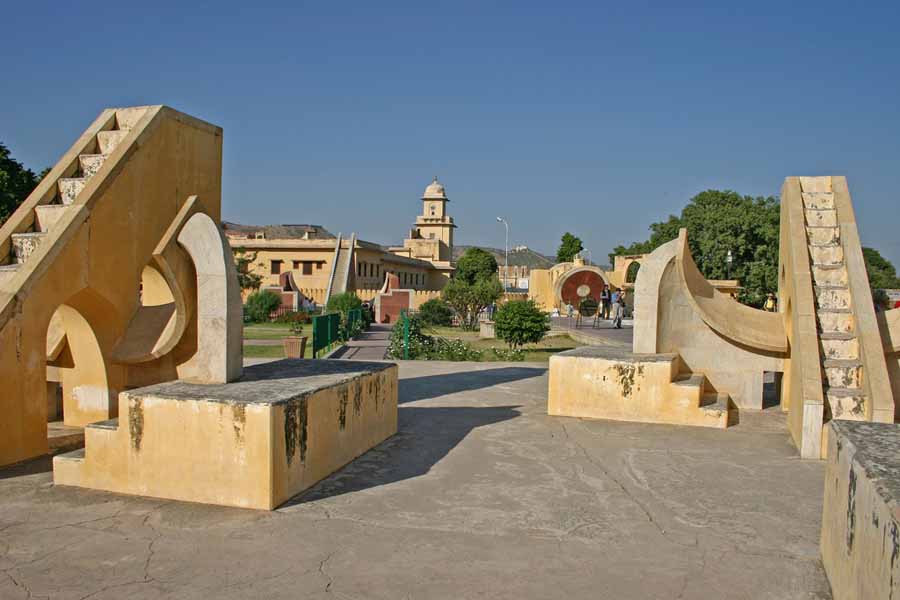

Jantar Mantar in Jaipur

Celestial Observatory

Tool for keeping track of the constellations

Sun Dial

Jantar Mantar in Jaipur

The Jantar Mantar in Jaipur is actually one of six major observatories built by the Maharajah. The one in Jaipur not only follows the movements of the sun and the moon to help determine auspicious dates for events, it also helps map out the position of the stars in the sky. Although no telescopic instruments were available at the time, the precise observation of the stars was greatly facilitated by observatories such as Jantar Mantar.

It should also be noted that such an endeavor (six major observatories, a staff of full-time priests etc.) did not come to a small cost. This is further evidence of the importance placed on the study of the stars. As mentioned earlier, both astrology and astronomy were reasons to build these structures. Unlike the "west", astrology did not become as pseudo-science as astronomy became more factual and experimental. Instead, both were considered an integral part of society.

Ancient India's contributions in the field of astronomy are well known and well documented. The earliest references to astronomy are found in the Rig Veda, which are dated 2000 BC. During next 2500 years, by 500 AD, ancient Indian astronomy has emerged as an important part of Indian studies and its affect is also seen in several treatises of that period. In some instances, astronomical principles were borrowed to explain matters, pertaining to astrology, like casting of a horoscope. Apart from this linkage of astronomy with astrology in ancient India, science of astronomy continued to develop independently, and culminated into original findings, like:

There are astronomical references of chronological significance in the Vedas. Some Vedic notices mark the beginning of the year and that of the vernal equinox in Orion. This was the case around 4500 BC. Fire altars, with astronomical basis, have been found in the third millennium cities of India. The texts that describe their designs are conservatively dated to the first millennium BC, but their contents appear to be much older.

Yajnavalkya (perhaps 1800 BC) advanced a 95-year cycle to synchronize the motions of the sun and the moon.A text on Vedic astronomy that has been dated to 1350 BC, was written by Lagadha.

In 500 AD, Aryabhata presented a mathematical system that took the earth to spin on its axis and considered the motions of the planets with respect to the sun (in other words it was heliocentric). His book, the Aryabhatya, presented astronomical and mathematical theories in which the Earth was taken to be spinning on its axis and the periods of the planets were given with respect to the sun.

In this book, the day was reckoned from one sunrise to the next, whereas in his Aryabhata-siddhanta he took the day from one midnight to another. There was also difference in some astronomical parameters.

Aryabhata wrote that 1,582,237,500 rotations of the Earth equal 57,753,336 lunar orbits. This is an extremely accurate ratio of a fundamental astronomical ratio (1,582,237,500/57,753,336 = 27.3964693572), and is perhaps the oldest astronomical constant calculated to such accuracy.Brahmagupta (598-668) was the head of the astronomical observatory at Ujjain and during his tenure there wrote a text on astronomy, the Brahmasphutasiddhanta in 628.

Bhaskara (1114-1185) was the head of the astronomical observatory at Ujjain, continuing the mathematical tradition of Brahmagupta. He wrote the Siddhantasiromani which consists of two parts: Goladhyaya (sphere) and Grahaganita (mathematics of the planets).

The other important names of historical astronomers from India are Madhava and Nilakantha.

On April 19, 1975, India sent into orbit its first satellite Aryabhatta. In 1984, Rakesh Sharma became the first Indian to go to outer space. Kalpana Chawla, later a US citizen, became the first woman of Indian origin to go to space.

Early cultures identifed celestial objects with gods and spirits. They related these objects (and their movements) to phenomena such as rain, drought, seasons, and tides. It is generally believed that the first "professional" astronomers were priests (Magi), and that their understanding of the "heavens" was seen as "divine", hence astronomy's ancient connection to what is now called astrology. Ancient constructions with astronomical alineations (such as Stonehenge) probably fulfilled both astronomical and religious functions.

Calendars of the world have usually been set by the Sun and Moon (measuring the day, month and year), and were of importance to agricultural societies, in which the harvest depended on planting at the correct time of year. The most common modern calendar is based on the Roman calendar, which divided the year into twelve months of alternating thirty and thirty-one days apiece. In 46 BC Julius Caesar instigated calendar reform and created the leap year.

There are astronomical references of chronological significance in the Vedas. Some Vedic notices mark the beginning of the year and that of the vernal equinox in Orion - this was the case around 4500 BC. Fire altars, with astronomical basis, have been found in the third millennium cities of India. The texts that describe their designs are conservatively dated to the first millennium BC, but their contents appear to be much older.

Yajnavalkya (perhaps 1800 BC) described the motions of the Sun and the Moon in his book Shatapatha Brahmana, and also advanced a 95-year cycle to synchronize the motions of the Sun and the Moon.

The Vedanga Jyotisha, a text on Vedic astrology that has been dated to 1350 BC, was written by Lagadha. It describes rules for tracking the motions of the Sun and the Moon, and also develops the use of geometry and trigonometry for astronomical uses.

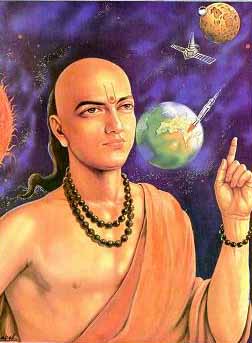

Aryabhata

In Indian languages, the science of astronomy is called Khagola-shastra. The word Khagola perhaps is derived from the famous astronomical observatory at the University of Nalanda which was called Khagola. It was at Khagola that the famous 5th century Indian Astronomer Aryabhatta studied and extended the subject.

Around 500 BCE, Aryabhata presented a mathematical system that took the Earth to spin on its axis and considered the motions of the planets with respect to the Sun. He also made an accurate approximation of the Earth's circumference and diameter, and also discovered how the lunar eclipse and solar eclipse happen for the first time. He gives the radius of the planetary orbits in terms of the radius of the Earth/Sun orbit as essentially their periods of rotation around the Sun. He was also the earliest to discover that the orbits of the planets around the Sun are ellipses.

He is the first known astronomer on that continent to have used a continuous system of counting solar days. His book, The Aryabhatiya, published in 498 AD described numerical and geometric rules for eclipse calculations. Indian astronomy at that time was taking much of its lead from cyclic Hindu cosmology in which nature operated in cycles, setting the stage for searching for numerical patterns in the expected time frames for eclipses.

Aryabhatta is said to have been born in 476 A.D. at a town called Ashmaka in today's Indian state of Kerala. When he was still a young boy he had been sent to the University of Nalanda to study astronomy. He made significant contributions to the field of astronomy. He also propounded the Heliocentric theory of gravitation, thus predating Copernicus by almost one thousand years.

Aryabhatta's Magnum Opus, the Aryabhattiya was translated into Latin in the 13th century. Through this translation, European mathematicians got to know methods for calculating the areas of triangles, volumes of spheres as well as square and cube root. Aryabhatta's ideas about eclipses and the sun being the source of moonlight may not have caused much of an impression on European astronomers as by then they had come to know of these facts through the observations of Copernicus and Galileo.

But considering that Aryabhatta discovered these facts 1,500 years ago, and 1,000 years before Copernicus and Galileo makes him a pioneer in this area too. Aryabhatta's methods of astronomical calculations expounded in his Aryabhatta-Siddhatha were reliable for practical purposes of fixing the Panchanga (Hindu calendar). Thus in ancient India, eclipses were also forecast and their true nature was perceived at least by the astronomers.

The lack of a telescope hindered further advancement of ancient Indian astronomy. Though it should be admitted that with their unaided observations with crude instruments, the astronomers in ancient India were able to arrive at near perfect measurement of astronomical movements and predict eclipses. Indian astronomers also propounded the theory that the Earth was a sphere. Aryabhatta was the first one to have propounded this theory in the 5th century.

Another Indian astronomer and mathematician, Brahmagupta estimated in the 7th century that the circumference of the earth was 5000 yojanas. A yojana is around 7.2 kms. Calculating on this basis we see that the estimate of 36,000 kms as the Earth's circumference comes quite close to the actual circumference known today.

There is an old Sanskrit Sloka (couplet) which is as follows:

This couplet means that there are suns in all directions. This couplet which describes the night sky as full of suns, indicates that in ancient times Indian astronomers had arrived at the important discovery that the stars visible at night are similar to the Sun visible during day time. In other words, it was recognized that the sun is also a star, though the nearest one. This understanding is demonstrated in another Sloka which says that when one sun sinks below the horizon, a thousand suns take its place. This apart, many Indian astronomers had formulated ideas about gravity and gravitation.

Brahmagupta, in the 7th century had said about gravity that "Bodies fall towards the Earth as it is in the nature of the Earth to attract bodies, just as it is in the nature of water to flow".

About a hundred years before Brahmagupta, another astronomer, Varahamihira had claimed for the first time perhaps that there should be a force which might be keeping bodies stuck to the Earth, and also keeping heavenly bodies in their determined places. Thus the concept of the existence of some attractive force that governs the falling of objects to the Earth and their remaining stationary after having once fallen; as also determining the positions which heavenly bodies occupy, was recognized.

It was also recognized that this force is attractive force. The Sanskrit term for gravity is Gurutvakarshan which is an amalgam of Guru-tva-akarshan. Akarshan means to be attracted, thus the fact that the character of this force was of attraction was also recognized. This apart, it seems that the function of attracting heavenly bodies was attributed to the sun.

The term Gurutvaakarshan can be interpreted to mean, 'to the attracted by the Master". The sun was recognized by all ancient people to be the source of light and warmth. Among the Aryans the sun was defiled.

The sun (Surya) was one of the chief deities in the Vedas. He was recognized as the source of light (Dinkara), source of warmth (Bhaskara). In the Vedas he is also referred to as the source of all life, the center of creation and the center of the spheres. The last statement is suggestive of the sun being recognized as the centre of the universe (solar system). The idea that the sun was looked upon as the power that attracts heavenly bodies is supported by the virile terms like Raghupati and Aditya used in referring to the sun.

While the male gender is applied to refer to the sun, the Earth (Prithivi, Bhoomi, etc.) is generally referred to as a female. The literal meaning of the term Gurutvakarshan also supports the recognition of the heliocentric theory, as the term Guru corresponds with the male gender, hence it could not have referred to the earth which was always referred to as a female.

Many ancient Indian astronomers have also referred to the concept of heliocentrism. Aryabhata has suggested it in his treatise Aryabhattiya. Bhaskaracharya has also made references to it in his Magnum Opus Siddhanta-Shiromani. But it has to be conceded that the heliocentric theory of gravitation was also developed in ancient times (i.e. around 500 B.C.) by Greek astronomers.

What supports the contention that it could have existed in India before the Greek astronomers developed it, is that in Vedic literature the Sun is referred to as the 'center of spheres' along with the term Guru-tva-akarshan which seemingly refers to the sun. The Vedas are dated around 3000 B.C. to 1000 B.C. Thus the heliocentric idea could have existed in a rudimentary form in the days of the Rig Veda and was refined further by astronomers of a later age.

Indian Astronomers like Aryabhatta and Varahamihira who lived between 476 and 587 A.D. made close approaches to the concept of Heliocentrism. In the Surya-Siddhanta, an astronomical text dated around 400 A.D., the following appellations have been given to the sun. "He is denominated the golden wombed (Hiranyagarbha), the blessed; as being the generator".

He is also referred to as "The supreme source of light (Jyoti) upon the bo

rder of darkness - he revolves. bringing beings into being, the creator of creatures". The Surya-Siddhanta also says that "Bestowing upon him the scriptures (Vedas) as gifts and establishing him within the egg as grandfather of all worlds, he himself then revolves causing existence". Thus we can see that what ancient Indian astronomers say comes close to the heliocentric theory of gravitation, which was a thousand years later articulated by Copernicus and Galileo inviting severe reactions from the clergy in Rome.Brahmagupta (598-668) was the head of the astronomical observatory at Ujjain and during his tenure there wrote a text on astronomy, the Brahmasphutasiddhanta in 628. He was the earliest to use algebra to solve astronomical problems. He also develops methods for calculations of the motions and places of various planets, their rising and setting, conjunctions, and the calculation of eclipses of the Sun and the Moon.

Bhaskara (1114-1185) was the head of the astronomical observatory at Ujjain, continuing the mathematical tradition of Brahmagupta. He wrote the Siddhantasiromani which consists of two parts: Goladhyaya (sphere) and Grahaganita (mathematics of the planets). He also calculated the time taken for the Earth to orbit the sun to 9 decimal places.

Other important astronomers from India include Madhava, Nilakantha Somayaji and Jyeshtadeva, who were members of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics from the 14th century to the 16th century. They were responsible for founding calculus and modern mathematical analysis, along with a number of other developments.

The Hindu Astronomy is one of the ancient astronomical systems of the world. It is sometimes considered a controversial subject, because some scholars argue that it shows a higher antiquity of the Vedic culture as generally assumed.

The astronomy and the astrology of India are based upon sidereal calculations. The sidereal astronomy is based upon the stars and the sidereal period is the time that it takes the object to make one full orbit around the Sun, relative to the stars. This is considered to be an object's true orbital period.In Hindu Astronomy, the vernal equinox (the First Point of Aries) is often calculated at 23¡ from 0¡ Aries (1950 CE), i.e. about 7¡ Pisces (Frawley 1991:148). The constellation that marks this vernal equinox is the Uttarabhadra.

In the time of the Puranas, the vernal equinox was marked by the Ashwini constellation (beginning of Aries), which gives a date of about 300-500 CE.

The Vishnu Purana (2.8.63) states that the equinoxes occur when the Sun enters Aries and Libra, and that when the sun enters Capricorn, his northern course (from winter to summer solstice) commences, and the southern course when he enters Cancer.

In the Suryasiddhanta, the rate of precession at 54" (it actually is 50.3"), which is much more accurate than the number calculated by the Greeks (Frawley 1991:148).

The Hindus use a system of 27 or 28 Nakshatras (lunar constellations) to calculate a month. Each month can be divided into 30 lunar tithis (days). There are usually 360 or 366 days in a year.

The Hindu astronomer Varahamihira, Garga (quoted by Somakara), the Mahabharata and the Vedanga Jyothish refer to the constellation Dhanishta (Shravishta) and thus to an ancient calendar that would have been used in 1280 BCE (see Frawley 1991: 152 ff.).

The Kaushiktaki Brahmana and possibly the Atharva Veda refer to a similar calendar (Frawley 1991).

The Atharva Veda, the Tandya Mahabrahmana and Laughakshi (quoted by Somakara) may show knowledge of an earlier calendar, but still in the Magha constellation (Frawley 1991). In still earlier Hindu calendars, the vernal equinox was in the Krittika constellation.

There are additionally references to the summer solstice in the Magha constellation.

This could indicate a date around 2000 BCE. The Atharva Veda, the Taittiriya Brahmana, the Shatapahta Brahmana, the Maitriyani Upanishad and the Vishnu Purana show such a constellation in the Krittika (Frawley 1991).

In the working out of horoscopes (called Janmakundali), the position of the Navagrahas, nine planets plus Rahu and Ketu (mythical demons, evil forces) was considered. The Janmakundali was a complex mixture of science and dogma. But the concept was born out of astronomical observations and perception based on astronomical phenomenon. In ancient times personalities like Aryabhatta and Varahamihira were associated with Indian astronomy.

It would be surprising for us to know today that this science had advanced to such an extent in ancient India that ancient Indian astronomers had recognized that stars are same as the sun, that the sun is center of the universe (solar system) and that the circumference of the Earth is 5,000 Yojanas. One Yojana being 7.2 kms., the ancient Indian estimates came close to the actual figure.