Puma Punku Ruins in Bolivia

Putting the Pieces of the Puzzle Together

Sacred sites found throughout the world seems follow the same geometric blueprint. Most remain an enigma that captivates the audience of those who come to visit especially those bells on powerful Leylines and grids, which activate human consciousness, when visited.

The origins of most ancient civilizations come from travelers from the stars that may be called gods or extraterrestrials, who are depicted in legends, petroglyphs, and enigmatic monuments and ruins.

The Incan ruins tell their own story about we are, why, we are here, and perhaps what the future holds for the human race.

Puma Punku Ruins in Bolivia

Putting the Pieces of the Puzzle Together

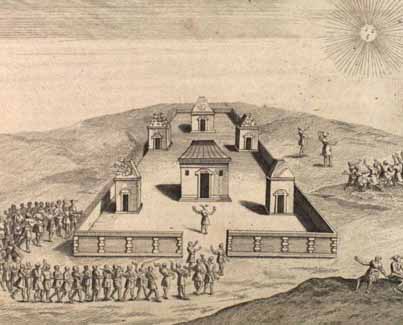

Sacsayhuaman (satisfied falcon) - is an Incan sacred and strategic site above the city, serves as the head of the puma. On the peak of a hill overlooking the city of Cusco lies the ancient fortress of Sacsayhuaman .

Once the domain of Inca warriors, nobles and engineers it now stands in ruins but many visitors explore its maze of intricately constructed walls, stairways and structures. After the conquest of Cusco in 1536 most of the inner structures of Sacsayhuaman were dismantled and used to construct Spanish Cusco.

The carved stone walls fit so perfectly that no blade of grass or steel can slide between them. There is no mortar. They often join in complex and irregular surfaces that would appear to be a nightmare for the stonemason. There is usually neither adornment nor inscription. It reminds me of the stones of the Great Pyramid. That too has no inscriptions. One has to wonder who created these great stone edifices with such precision in that timeline with such limited tools.

Most of the walls are found at Cuzco and the Urubamba River Valley in the Peruvian Andes with a few scattered examples elsewhere in the Andes.

Sacsahuaman was supposedly completed around 1508. It took approximately a crew of 20,000 to 30,000 men working for 60 years to complete it.

Chronicler Garcilaso de la Vega was born around 1530, and raised in the shadow of these walls. He wrote - "This fortress surpasses the constructions known as the seven wonders of the world. For in the case of a long broad wall like that of Babylon, or the colossus of Rhodes, or the pyramids of Egypt, or the other monuments, one can see clearly how they were executed. They did it by summoning an immense body of workers and accumulating more and more material day by day and year by year.

They overcame all difficulties by employing human effort over a long period. But it is indeed beyond the power of imagination to understand now these Indians, unacquainted with devices, engines, and implements, could have cut, dressed, raised, and lowered great rocks, more like lumps of hills than building stones, and set them so exactly in their places. For this reason, and because the Indians were so familiar with demons, the work is attributed to enchantment."

Archaeologists tell us that the walls of Sacsahuaman rose ten feet higher than their remnants. That additional ten feet of stones supplied the building materials for the cathedrals and casas of the conquistadors. It is generally conceded that these stones were much smaller than those lithic monsters that remain. Perhaps the upper part of the walls, constructed of small, regularly-shaped stones was the only part of Sacsahuaman that was built by the Incas and finished in 1508. This could explain why no one at the time of the conquest seemed to know how those mighty walls were built.

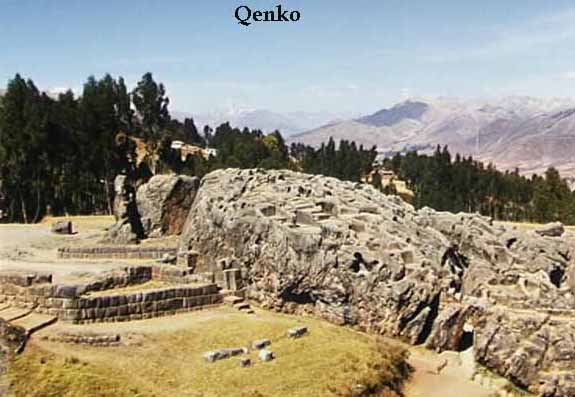

Near Sacsayhuaman is Qenko (Zigzag), a carved limestone formation

that served as a sacrificial site or temple.

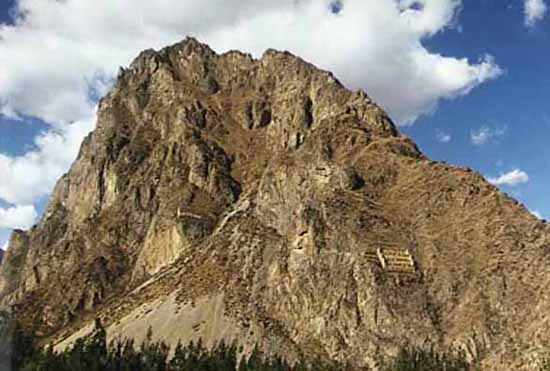

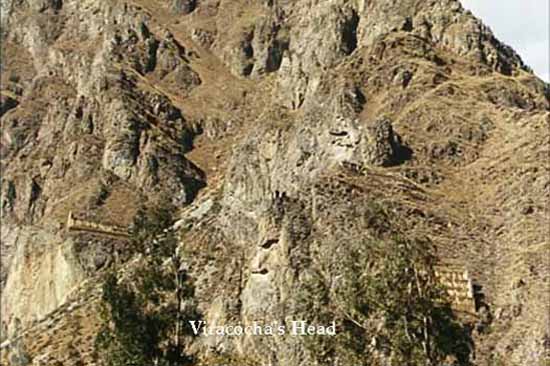

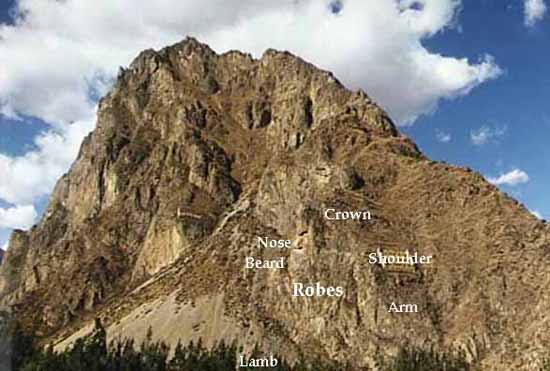

Across from the ruins of Ollantaytambo in the Urubamba Valley stands a sacred mountain believed to have the profile of Viracocha, the Inca sun god, carved into the stone.

When the sun strikes this profile of Viracocha during the winter solstice, the mineral content of the mountain reflects and refracts the rays. The Inca believed that this was a sign verifying the deity of Viracocha. The solstices were sacred days for the Inca since so much of their culture was based on planting seasons. The buildings to the right and to the left were constructed by the Inca to store corn as food for winters and as offerings to Viracocha.

Nazca Lines

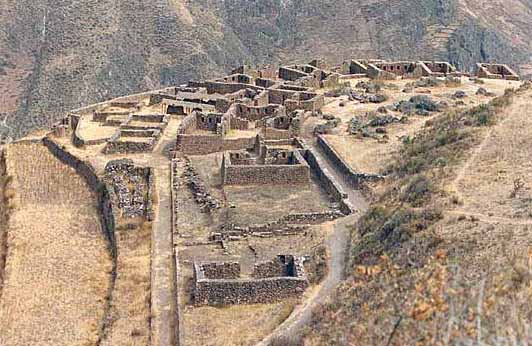

Ollantaytamb (Quechua: Ullantaytampu) is a town and an Inca archaeological site in southern Peru some 72 km (45 mi) by road northwest of the city of Cusco. It is located at an altitude of 2,792 m (9,160 ft) above sea level in the district of Ollantaytambo, province of Urubamba, Cusco region.

During the Inca Empire, Ollantaytambo was the royal estate of Emperor Pachacuti, who conquered the region 73 and built the town and a ceremonial center. At the time of the Spanish conquest of Peru, it served as a stronghold for Manco Inca Yupanqui, leader of the Inca resistance. Located in the Sacred Valley of the Incas, it is now an important tourist attraction on account of its Inca ruins and its location en route to one of the most common starting points for the four-day, three-night hike known as the Inca Trail.

Around the mid-15th century, the Inca emperor Pachacuti conquered and razed Ollantaytambo; the town and the nearby region were incorporated into his personal estate. The emperor rebuilt the town with sumptuous constructions and undertook extensive works of terracing and irrigation in the Urubamba Valley; the town provided lodging for the Inca nobility, while the terraces were farmed by yanakuna, retainers of the emperor. After Pachacuti's death, the estate came under the administration of his panaqa, his family clan.

During the Spanish conquest of Peru, Ollantaytambo served as a temporary capital for Manco Inca, leader of the native resistance against the conquistadors. He fortified the town and its approaches in the direction of the former Inca capital of Cusco, which had fallen under Spanish domination.

In 1536, on the plain of Mascabamba, near Ollantaytambo, Manco Inca defeated a Spanish expedition in what is known as Battle of Ollantaytambo, blocking their advance from a set of high terraces and flooding the plain. Despite his victory, however, Manco Inca did not consider his position tenable, so the following year, he withdrew to the heavily forested site of Vilcabamba, where he established the Neo-Inca State.

In 1540, the native population of Ollantaytambo was assigned in encomienda to Hernando Pizarro.

In the 19th century, the Inca ruins at Ollantaytambo attracted the attention of several foreign explorers; among them, Clements Markham, Ephraim Squier, Charles Wiener, and Ernst Middendorf published accounts of their findings.

Hiram Bingham III stopped here in 1911 on his journey up the Urubamba River in search of Machu Picchu.

Cuzco, the capital of the Incan empire, was built out of stone and adorned with gold. The Coricancha is a fine example of how the fusion of Inca style and Colonial styles of architecture evolved into the Cusco of today. Originally the site was a ceremonial center featuring a number of stone rectangular buildings laid out as to be the convergence of ley lines connected to numerous 'huacas' or power spots.

On the Summer Solstice sun light from the opening in one of the rooms illuminates a specific niche in which sits the Inca chief. The rooms were adorned with elaborate gold ceremonial objects including a huge gold sun disk which was considered sacred. After the Spanish Conquest much of the structure was torn down and reassembled as the Church of Santa Domingo. A considerable amount of the original Inca structure was left intact and integrated into the church structure.

The Temple of the Sun was once the most important temple of the Incas. When the Spanish conquered the Inca Empire, they used the fine Inca stonework to form the base of the Church of Santo Domingo. Inside the church area are some of the buildings built by the Incas that were used by the conquerors for their private quarters.

The temple also served as a tomb for several Incas, or kings. During Inca rule, the Coricancha, or Golden Courtyard, was covered with gold and silver sculptures representing llamas, corn, babies, and the sun.

When the Spaniards conquered Cuzco, the Inca capital, they set about stripping the gold from the temples and melting them down. Legend has it that it took three months to cart all of the gold from the Sun Temple.

Not far from Cusco there is a hill they call the Temple of the Moon. The hill has several caves and many rock carvings. Some of the carvings here show extreme weathering. This most likely was used for ceremonial purposes.

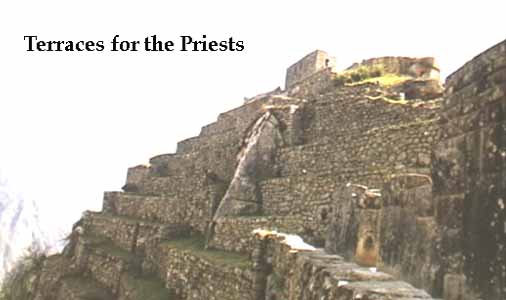

In the foreground was the city's quarry. Midfield are agricultural terraces, probably for the typical resident. In the background is the Inca Trail winding up the mountain for which the city is named.

These unusual Incan terraces at Moray were an experimental farm taking

advantage of different micro-climates created by the geometric shapes.

At the southern end of the Sacred Valley, Pisac's ruins form an enormous condor on the mountainside. Farmers still cultivate the terraces that lead up to the city at the top of the mountain. See the altar at the temple and walk through the rock tunnel.

Strange Stone Carvings

Steps that go nowhere - seats that are hard to get to - are to be found in astonishing abundance in the area around Cusco. They are carved so precisely, with their outside and inside corners so sharp and fine.