Friday the 13th - January 13, 2006

In the morning, the spirit of a woman came to me and told me I would read her daughter that day. She told me write to write a blog about the Evil Eye. Though I am not much for superstitions, I am attracted to the word Eye. In most languages the name translates literally into English as "bad eye", "evil eye", "evil look", or just "the eye".

Hours later ...

My first client, Barbara, came to speak to her mother, Mary, who crossed over in December 2005. There was something about Mary ... As we spoke, Mary showed me an evil eye and I remembered her visit earlier that morning. Barbara, explained that her mother, who was of Greek heritage, believed in the Evil Eye and often mentioned that it had to do with the way her life unfolded through the decades. To believe or not to believe, that is the question.

The most common form, however, attributes the cause to envy, with the envious person casting the evil eye doing so unintentionally. Also the effects on victims vary. Some cultures report afflictions with bad luck; others believe the evil eye can cause disease, wasting away, and even death. In most cultures, the primary victims are thought to be babies and young children, because they are so often praised and commented upon by strangers or by childless women. The late UC Berkeley professor of folklore Alan Dundes has explored the beliefs of many cultures and found a commonality that the evil caused by the gaze is specifically connected to symptoms of drying, desiccation, withering, and dehydration, that its cure is related to moistness, and that the immunity from the evil eye that fishes have in some cultures is related to the fact that they are always wet. His essay "Wet and Dry: The Evil Eye" is a standard text on the subject.

In many forms of the evil eye belief, a person - otherwise not malefic in any way - can harm adults, children, livestock, or a possession, simply by looking at them with envy. The word "evil" can be seen as somewhat misleading in this context, because it suggests that someone has intentionally "cursed" the victim. A better understanding of the term "evil eye" can be gained from the old English word for casting the evil eye, namely "overlooking," implying that the gaze has remained focused on the coveted object, person, or animal for too long.

While some cultures hold that the evil eye is an involuntary jinx cast unintentionally by people unlucky enough to be cursed with the power to bestow it by their gaze, others hold that, while perhaps not strictly voluntary, the power is called forth by the sin of envy. In Jewish religious thought, it is sometimes asserted that the one who looks upon another with envy is not always at fault, but that the envy may be perceived by God, who then may redress the balance between two people by bringing the higher one low. It has been suggested that the term covet (to eye enviously) in the tenth Commandment refers to casting the evil eye, rather than to simple desire or envy.

Belief in the evil eye is strongest in the Middle East, South Asia, Central Asia (Turkic Languages Speaking People) and Europe, especially the Mediterranean region; it has also spread to other areas, including northern Europe, particularly in the Celtic regions, and the Americas, where it was brought by European colonists and Middle Eastern immigrants.

Although the concept of cursing by staring or gazing is largely absent in East Asian and Southeast Asian societies, the usog curse is an exception.

Belief in the evil eye features in Islamic mythology; it is not a part of Islamic doctrine, however, and is more a feature of folk religion. The practice of warding the evil eye is also common within Muslims (though once again without evidence from an Islamic doctrine). Muslims claim the Qu'ran states to seek refuge from the "mischief of the envious," but seeing as how that is closest quote from the Qu'ran supporting the evil eye, it is plausible to negate or deny this belief, simply because the Qu'ran does not clarify. In the Islamic areas of the Middle East, rather than directly expressing appreciation of, for example, a child's beauty, it is customary to say Masha'Allah, that is, "God has willed it".

In Greece and Turkey, evil eye jewelry and trinkets are particularly common. Colourful beads, bracelets, necklaces, anklets, and all manner of decoration may be adorned by this particularly popular symbol, and it is common to see it on almost anything, from babies, horses, doors to cars, cell phones and even airplanes.

In Latin, the evil eye was fascinum, the origin of the English word "to fascinate".

In Italian the evil is called jettatura or mal' occhio, in Greek baskania or matiasma. The evil eye belief also spread to northern Europe, especially the Celtic regions.

The evil eye is equally significant in Jewish folklore. Ashkenazi Jews in Europe and the Americas routinely exclaim Keyn aynhoreh! (also spelled Kein ayin hara!), meaning "No evil eye!" in Yiddish, to ward off a jinx after something or someone has been rashly praised or good news has been spoken aloud. In the Aegean region and other areas where light-colored eyes are relatively rare, people with green eyes are thought to bestow the curse, intentionally or unintentionally. This belief may have arisen because people from cultures unused to the evil eye, such as Northern Europe, are likely to transgress local customs against staring or praising the beauty of children. Thus, in Greece and Turkey amulets against the evil eye take the form of blue eyes, and in the painting by John Phillip, above, we witness the culture-clash experienced by a woman who suspects that the artist's gaze implies that he is looking at her with the evil eye.

Among those who do not take the evil eye literally, either by reason of the culture in which they were raised or because they simply do not believe in such things, the phrase, "to give someone the evil eye" usually means simply to glare at the person in anger or disgust.

Attempts to ward off the curse of the evil eye have resulted in a number of talismans in many cultures. As a class, they are called "apotropaic" (prophylactic or "protective") talismans, meaning that they turn away or turn back harm.

Disks or balls, consisting of concentric blue and white circles (usually, from inside to outside, dark blue, light blue, white, dark blue) representing an evil eye are common apotropaic talismans in the Middle East, found on the prows of Mediterranean boats and elsewhere; in some forms of the folklore, the staring eyes are supposed to bend the malicious gaze back to the sorcerer.

Known as nazar (Turkish: nazar boncugu or nazarlők), this talisman is particularly common in Turkey, found in or on houses and vehicles or worn as beads.

A blue eye can also be found on some forms of the hamsa hand, an apotropaic hand-shaped amulet against the evil eye found in the Middle East. The word hamsa, also spelled khamsa, and spelled as hamesh, means "five" referring to the fingers of the hand. In Jewish culture, the hamsa is called the Hand of Miriam; in Muslim culture, the Hand of Fatima.

Among Jews, fish are considered to be immune to the evil eye, so their images are often found on hamsa hand amulets. A red thread is also said to protect babies against the evil eye, and according to folkloric custom it is placed on the pillow upon which a newborn baby is presented for the first time at a viewing by family and friends. In the late 20th century it became the custom to wind a red string around the tomb of the great Matriarch, Rachel, located near Bethlehem, in the West Bank, then to cut the string into pieces and give them out to be worn on the left wrist as an effective protection against the evil eye. According to this custom, the left hand is considered to be the receiving side for the body and soul, and by wearing the red string on the left wrist, believers receive a vital connection to the protective energies surrounding the tomb of Rachel, carrying her protective energy with them and drawing from it any time there is need. The Kabbalah Centre puts much emphasis on this custom, which is virtually unknown in classical Kabbalah.

In ancient Rome, people believed that phallic charms and ornaments offered proof against the evil eye. Such a charm was called fascinum in Latin, from the verb fascinare (the origin of the English word "to fascinate"), "to cast a spell", such as that of the evil eye.

One such charm is the cornicello, which literally translates to "little horn". In modern Italian language, they are called Cornetti, with the same meaning. Sometimes referred to as the cornuto (horned) or the corno (horn), it is a long, gently twisted horn-shaped amulet. Cornicelli are usually carved out of red coral or made from gold or silver. The type of horn they are intended to copy is not a curled-over sheep horn or goat horn but rather like the twisted horn of an African eland or something similar.

Some theorists endorse the idea that the ribald suggestions made by sexual symbols would distract the witch from the mental effort needed to successfully bestow the curse. Others hold that since the effect of the eye was to dry up liquids, the drying of the phallus (resulting in male impotence) would be averted by seeking refuge in the moist female genitals. The fact that the hamsa hand, a non-phallic apotropaic amulet, is seen as the hand of a woman (Miriam by Jews and Fatima by Muslims) reinforces the idea that protection comes from the feminine element.

Among the Romans and their cultural descendants in the Mediterranean nations, those who were not fortified with phallic charms had to make use of sexual gestures to avoid the eye. This is one of the uses of the mano cornuto (a fist with the index and little finger extended, the heavy metal or "Hook 'em Horns" gesture) and the mano fico (a fist with the thumb pressed between the index and middle fingers, representing the phallus within the vagina). In addition to the phallic talismans, statues of hands in these gestures, or covered with magical symbols, were carried by the Romans as talismans. In Latin America, carvings of the mano fico continue to be carried as good luck charms.

In Greece, the evil eye is cast away though the process of xematiasma, whereby the "healer" silently recites a secret prayer passed over from an older relative of the opposite sex, usually a grandparent. Such prayers are revealed only under specific circumstances, for according to superstition those who reveal them indiscriminately lose their ability to cast off the evil eye. There are several regional versions of the prayer in question, a common one being: "Holy Virgin, Our Lady, if so and so is suffering of the evil eye release him/her of it" repeated thrice. According to custom, if one is indeed afflicted with the evil eye, both victim and "healer" then start yawning profusely. The "healer" then performs the sign of the cross three times, and spits in the air three times.

In India the evil eye, called "drishti" (literally view) or "nazar", is removed through "Aarthi". The actual removal involves different means as per the subject involved. In case of removing human evil eye, a traditional Hindu ritual of holy flame (on a plate) is rotated around the person's face so as to absorb the evil effects. Sometimes people will also be asked to spit into a handful of chillies kept in that plate, which are then thrown into fire. For vehicles too, this process is followed with limes or lemons being used instead of chillies. These lemons are crushed by the vehicle and another new lemon is hung with chillies in a bead to ward off any future evil eyes. The use of kumkum on cheeks of newly weds or babies is also a method of thwarting the "evil eye". Toddlers and young children are traditionally regarded as perfect so especially likely to attract the evil eye. Often mothers will apply kohl around their children's eyes to make their beauty imperfect and thus reduce their susceptibility to the evil eye. In Bangladesh young children often have large black dots drawn onto their foreheads in order to counter the evil eye.

In Iran, Iraq, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, the seeds of Aspand (Peganum harmala, also called Esfand, Espand, Esphand, and Harmal) are burned on charcoal, where they explode with little popping noises, releasing a fragrant smoke that is wafted around the head of those afflicted by or exposed to the gaze of strangers.

As this is done, an ancient Zoroastrian prayer is recited against Bla Band. This prayer is said by Muslims as well as by Zoroastrians in the region where Aspand is utilized against the evil eye. Some sources say that the popping of the seeds relates to the breaking of the curse or the popping of the evil eye itself (although this is not consistent with the idea that a particular person is casting the spell, since no one's eyes are expected to explode as a result of this ritual). In Iran at least, this ritual is sometimes performed in traditional restaurants, where customers are exposed to the eyes of strangers. Dried aspand capsules are also used for protection against the evil eye in parts of Turkey

. In Mexico and Central America, infants are considered at special risk for evil eye (see mal de ojo, above) and are often given an amulet bracelet as protection, typically with an eye-like spot painted on the amulet. Another preventive measure is allowing admirers to touch the infant or child; in a similar manner, a person wearing an item of clothing that might induce envy may suggest to others that they touch it or some other way dispel envy. One traditional cure in rural Mexico involves a curandero (folk healer) sweeping a raw chicken egg over the body of a victim to absorb the power of the person with the evil eye. The egg is later broken into a glass and examined. (The shape of the yolk is thought to indicate whether the aggressor was a man or a woman.) In the traditional Hispanic culture of the Southwestern United States and some parts of Mexico, an egg is passed over the patient and then broken into a bowl of water. This is then covered with a straw or palm cross and placed under the patient's head while he or she sleeps; alternatively, the egg may be passed over the patient in a cross-shaped pattern. The shape of the egg in the bowl is examined in the morning to assess success.

In 1946, the American magician Henri Gamache published a text called Protection against Evil, also called Terrors of the Evil Eye Exposed! which offers directions to defend oneself against the evil eye. Gamache's work brought evil eye beliefs to the attention of hoodoo practitioners in the southern United States.

Nowadays, giving another person the "evil eye" usually means glaring at the person in anger or disgust.

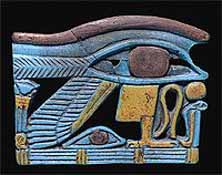

Eye of Horus

The Eye of Horus is an Ancient Egyptian symbol of protection and power. The Eye was a symbol that signified royal power. The ancients believed this symbol of indestructibility would assist in rebirth, due to their beliefs about the soul. The more recent tradition of freemasonry adopted the symbol and as such it has survived to this day, and appears as the Eye of Providence on the recto of the Great Seal of the United States. The Eye of Horus (flanked by Nekhbet and Wadjet) was found under the 12th layer of bandages on Tutankhamun's mummy.

Horus was an ancient god in Egyptian mythology who dramatically evolved over the whole of Egyptian history. Early on, he became identified as a sky god, where one of his eyes was the sun, and the other the moon. His weaker eye later became less important in his mythology, and he became more strongly aligned with the sun, particularly when the cult of Thoth, a moon god, arose. As the sun, or rather, with his eye as the sun, his eye had a special meaning, and became a symbol of power. Originally, Ra held this position, but as Horus gradually became more important, he transformed into a sun god, so Horus became thought of as Ra, or rather Ra-Herakhty ("Ra, who is Horus of the two horizons").

The Eye of Horus is commonly used in modern times. One example is the Rx symbol used in medicine and pharmaceuticals. Though, the Rx really is an abbreviation of the Latin word for "recipe" however other texts conclude that it is an invocation to the God Jupiter and that the symbol is a corruption of the symbol for Jupiter. In its original use, the Rx was drawn as an eye with a leg, or the Eye of Horus.

Superstitions