From Hunter Gatherer to Early Farmers

Early humans dined on giant sloths and other Ice Age giants, archaeologists find PhysOrg - October 2, 2025

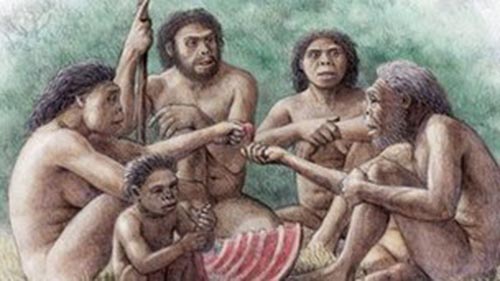

What did early humans like to eat? The answer, according to a team of archaeologists in Argentina, is extinct megafauna, such as giant sloths and giant armadillos. In a study What did early humans like to eat? The answer, according to a team of archaeologists in Argentina, is extinct megafauna, such as giant sloths and giant armadillos. In a study published in the journal Science Advances, researchers demonstrate that these enormous animals were a staple food source for people in southern South America around 13,000 to 11,600 years ago. Their findings may also rewrite our understanding of how these massive creatures became extinct.researchers demonstrate that these enormous animals were a staple food source for people in southern South America around 13,000 to 11,600 years ago. Their findings may also rewrite our understanding of how these massive creatures became extinct.

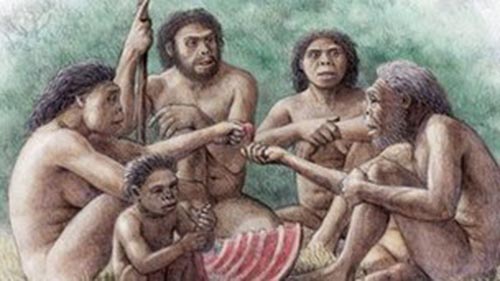

Revealing the menu of farmers 5,000 years ago - Funnel Beaker Culture (4000-2800 BCE) PhysOrg - January 18, 2025

The so-called Funnel Beaker Culture (4000-2800 BCE) represents the first phase in Southern Scandinavia/northern Germany in which people were agriculturalists and kept livestock. The lifestyle of these farmers has been a subject of research for decades. However, up to now, a mystery has remained regarding the preferred plant food ingredients, especially those beyond cereals, and which product was made from cereal grain. At Oldenburg LA 77, multiple lines of evidence from grinding stone analyses suggest that cereal grains might have been crushed into coarse fragments and/or ground into fine flour. Together with the botanical and chemical analysis of food residues encrusted on Oldenburg LA77 pottery, and in particular, the biomarker evidence for cereal grains from a "baking plate" recently published, all the evidence together indicates a possible production of flatbread.

Earliest Known 3D Map Found in Prehistoric French Cavern used by Hunter Gathers Science Alert - January 8, 2025

In the cramped confines of a small cavern to the south of Paris, scientists have 'read between the lines' on the floor and discovered what could be the oldest surviving three-dimensional map of a hunter-gatherer territory. Around 20,000 years ago, the prehistoric people who sheltered in this cave carved and smoothed the stone floors to create what looks like a miniature model of the surrounding valley. As water from the outside world trickled through the carefully laid-out channels, basins, and depressions in the cave, the surface would have come alive with rivers, deltas, ponds, and hills. The accuracy of the drawing of this hydrographical network reveals a remarkable capacity for abstract thinking in those who drew it and in those for whom it was intended

How popcorn was discovered nearly 7,000 years ago Live Science - July 5, 2024

You have to wonder how people originally figured out how to eat some foods that are beloved today. The cassava plant is toxic if not carefully processed through multiple steps. Yogurt is basically old milk that’s been around for a while and contaminated with bacteria. And who discovered that popcorn could be a toasty, tasty treat?

Farming began in North Africa about 7,500 years ago thanks to immigrants, DNA from Neolithic burials reveals Live Science - February 5, 2024

Around 8,500 years ago, members of farming communities crossed the Aegean Sea, bringing techniques similar to those used in Anatolia to Greece and the Balkans. Five centuries later, some then made the crossing to Italy.

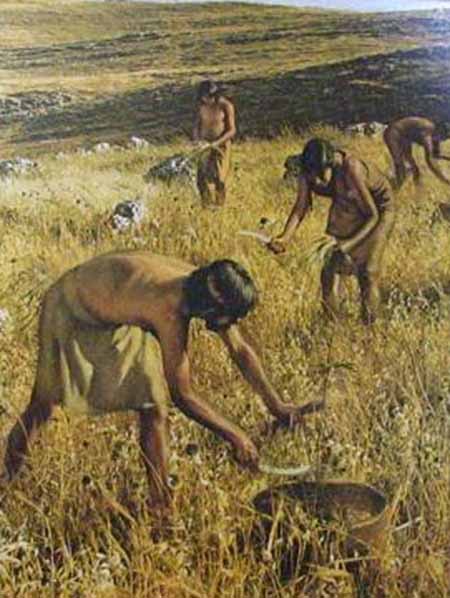

Who were the first farmers? Live Science - September 15, 2023

The development of farming by Homo sapiens may be the most fundamental advance of our species. It forever changed the nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles that all humans had followed until that time, and the farming practices established by our ancient ancestors still shape agriculture around the world today, feeding billions of people. Farming also led to villages and then to specialized labor, and then to the advancements of arts and technologies. But when did farming start? And why?

The real Paleo diet: New archaeological evidence changes what we thought about how ancient humans prepared food PhysOrg - November 27, 2022

Jazzing up your dinner is a human habit dating back at least 70,000 years. ew study showed both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens had complex diets involving several steps of preparation, and took effort with seasoning and using plants with bitter and sharp flavors. This degree of culinary complexity has never been documented before for Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers.

Getting to the roots of our ancient cousins' diet Science Daily - August 30, 2018

Since the discovery of the fossil remains of Australopithecus africanus from Taung nearly a century ago, and subsequent discoveries of Paranthropus robustus, there have been disagreements about the diets of these two South African hominin species. By analyzing the splay and orientation of fossil hominin tooth roots, researchers now suggest that Paranthropus robustus had a unique way of chewing food not seen in other hominins. The new study demonstrates that the orientation of tooth roots within the jaw has much to offer for an understanding of the dietary ecology of our ancestors and extinct cousins.

Ancient tooth shows Mesolithic ancestors were fish and plant eaters PhysOrg - June 1, 2018

Analysis of the skeletal remains of a Mesolithic man found in a cave on a Croatian island has revealed microscopic fish and plant remains in the dental plaque of a tooth – a first-time discovery for the period and region. Previous analysis of Mesolithic skeletal remains in this region has suggested a more varied Mediterranean diet consisting of terrestrial, freshwater and marine food resources, not too dissimilar to what modern humans eat today. Although this recent find is the only example of a skeleton that provides evidence of both fish and plants in the diet of early people in this region, the researchers argue that the discovery provides a significant insight into the lifestyle of Adriatic and Mediterranean foragers.

Entomologist confirms first Saharan farming 10,000 years ago PhysOrg - March 17, 2018

By analyzing a prehistoric site in the Libyan desert, a team of researchers from the universities of Huddersfield, Rome and Modena & Reggio Emilia has been able to establish that people in Saharan Africa were cultivating and storing wild cereals 10,000 years ago. In addition to revelations about early agricultural practices, there could be a lesson for the future, if global warming leads to a necessity for alternative crops.

Neolithic farmers coexisted with hunter-gatherers for centuries in Europe Science Daily - November 9, 2017

New research answers a long-debated question among anthropologists, archaeologists and geneticists: when farmers first arrived in Europe, how did they interact with existing hunter-gatherer groups? Did the farmers wipe out the hunter-gatherers, through warfare or disease, shortly after arriving? Or did they slowly out-compete them over time? The current study suggests that these groups likely coexisted side-by-side for some time before the farming populations slowly integrated local hunter-gatherers.

Scientists find world's oldest fossil mushroom PhysOrg - June 7, 2017

Roughly 115 million years ago, when the ancient supercontinent Gondwana was breaking apart, a mushroom fell into a river and began an improbable journey. Its ultimate fate as a mineralized fossil preserved in limestone in northeast Brazil makes it a scientific wonder. The mushroom somehow made its way into a highly saline lagoon, sank through the stratified layers of salty water and was covered in layer upon layer of fine sediments. In time - lots of it - the mushroom was mineralized, its tissues replaced by pyrite (fool's gold), which later transformed into the mineral goethite, the researchers report.

Baltic hunter-gatherers began farming without influence of migration, ancient DNA suggests PhysOrg - February 2, 2017

New research indicates that Baltic hunter-gatherers were not swamped by migrations of early agriculturalists from the Middle East, as was the case for the rest of central and western Europe. Instead, these people probably acquired knowledge of farming and ceramics by sharing cultures and ideas - rather than genes - with outside communities.

Fossil fruit from 52 million years ago revealed BBC - January 5, 2017

A fossilized fruit dating back 52 million years has been discovered in South America. The ancient berry belongs to a family of plants that includes popular foods such as potatoes, tomatoes and peppers. The plant family's early history is largely unknown as, until now, only a few seeds have been found in the fossil record. Scientists say the origins of the class go back much further than previously thought, by tens of millions of years.

Every grain of rice: Ancient rice DNA data provides new view of domestication history PhysOrg - July 26, 2016

Despite its importance on global palates and economies, the domestication and origins of rice have remained a mystery. The popular consensus is that japonica, the shorter stickier grain perfect for sushi, has been exclusively cultivated exclusively in northern part of East Asia. In northern parts of East Asia, consisting of Japan, Korea, and northern part of China, current rice production and consumption are japonica with very little exceptional use of indica.

Farming was spread into and across Europe by people originating in modern-day Greece and Western Turkey PhysOrg - June 6, 2016

Early farmers from across Europe have an almost unbroken trail of ancestry leading back to the Aegean. For most of the last 45,000 years Europe was inhabited solely by hunter-gatherers. About 8,500 years ago a new form of subsistence - farming - started to spread across the continent from modern-day Turkey, reaching central Europe by 7,500 years ago and Britain by 6,100 years ago. This new subsistence strategy led to profound changes in society, including greater population density, new diseases, and poorer health. Such was the impact of farming on how we live that scientists have debated for more than 100 years how it was spread across Europe. Many believed that farming was spread as an idea to European hunter-gatherers but without a major migration of farmers themselves.

New support for human evolution in grasslands: A 24-million-year record of African plants plumbs deep past PhysOrg - June 6, 2016

Buried deep in seabed sediments off east Africa, scientists have uncovered a 24-million-year record of vegetation trends in the region where humans evolved. The authors say the record lends weight to the idea that we developed key traits - flexible diets, large brains, complex social structures and the ability to walk and run on two legs - while adapting to the spread of open grasslands.

How diet shaped human evolution Science Daily - March 30, 2016

Homo sapiens, the ancestor of modern humans, shared the planet with Neanderthals, a close, heavy-set relative that dwelled almost exclusively in Ice-Age Europe, until some 40,000 years ago. Black carbon image of hunting on sandstone. The Ice-Age diet -- a high-protein intake of large animals -- triggered physical changes in Neanderthals, namely a larger ribcage and a wider pelvis. Neanderthals were similar to Homo sapiens, with whom they sometimes mated -- but they were different, too. Among these many differences, Neanderthals were shorter and stockier, with wider pelvises and rib-cages than their modern human counterparts.

New research shows same growth rate for farming, non-farming prehistoric people PhysOrg - December 21, 2015

Prehistoric human populations of hunter-gatherers in a region of North America grew at the same rate as farming societies in Europe, according to a new radiocarbon analysis. Transitioning farming societies experienced the same rate of growth as contemporaneous foraging societies.

Scientists peg Anthropocene to first farmers Science Daily - December 17, 2015

A new analysis of the fossil record shows that a deep pattern in the structure of plant and animal communities remained the same for 300 million years. Then, 6,000 years ago, the pattern was disrupted--at about the same time that people started farming in North America and populations rose. The research suggests that humans were the cause of this profound change in nature.

Eat a paleo peach - first fossil peaches discovered in southwest China PhysOrg - December 1, 2015

The sweet, juicy peaches we love today might have been a popular snack long before modern humans arrived on the scene. Scientists have found eight well-preserved fossilized peach endocarps, or pits, in southwest China dating back more than two and a half million years. Despite their age, the fossils appear nearly identical to modern peach pits.

Shift in human ancestors' diet earlier than previously thought Science Daily - September 15, 2015

Pre-humans' shift toward a grass-based diet took place about 400,000 years earlier than experts previously thought, providing a clearer picture of a time of rapid change in conditions that shaped human evolution. Millions of years ago, our primate ancestors turned from trees and shrubs to search for food on the ground. In human evolution, that has made all the difference. The shift toward a grass-based diet marked a significant step toward the diverse eating habits that became a key human characteristic, and would have made these early humans more mobile and adaptable to their environment.

Ancient DNA reveals how Europeans developed light skin and lactose tolerance PhysOrg - June 11, 2015

Food intolerance is often dismissed as a modern invention and a "first-world problem". However, a study analyzing the genomes of 101 Bronze-Age Eurasians reveals that around 90% were lactose intolerant. The research also sheds light on how modern Europeans came to look the way they do - and that these various traits may originate in different ancient populations. Blue eyes, it suggests, could come from hunter gatherers in Mesolithic Europe (10,000 to 5,000 BC), while other characteristics arrived later with newcomers from the East. About 40,000 years ago, after modern humans spread from Africa, one group moved north and came to populate Europe as well as north, west and central Asia. Today their descendants are still there and are recognizable by some very distinctive characteristics. They have light skin, a range of eye and hair colors and nearly all can happily drink milk.

Our ancient obsession with food PhysOrg - June 6, 2015

Amateur cook-offs like the hugely popular Master Chef series now in its seventh season in Australia have been part of our TV diet for almost two decades. These shows celebrate the remarkable lengths we humans will go to to whet the appetite, stimulate the senses, fire our neural reward systems and sustain the body. Yet, few of us pause to reflect on the hugely important role diet plays in the ecology and evolutionary history of all species, including our own. So much of what we read about human evolution portrays the protagonists as unwitting players in a game of chance: natural selection acting through external environmental factors beyond their control and sealing their evolutionary fate. Yet, all species influence their environment through the normal ecological interactions that occur in every ecosystem, such as between predators and their prey. Such interactions shape ecosystems over long time scales and are profoundly important in terms of evolution. When a species alters its environment and influences its own evolution, becomes as 'co-director' if you will, the process is dubbed 'niche construction'.

Scientists find evidence of wheat in UK 8,000 years ago BBC - February 27, 2015

Wheat was present in Britain 8,000 years ago, according to new archaeological evidence. Fragments of wheat DNA recovered from an ancient peat bog suggests the grain was traded or exchanged long before it was grown by the first British farmers. The grain was found at what is now a submerged cliff off the Isle of Wight.

Tooth Tales: Prehistoric Plaque Reveals Early Humans Ate Weeds Live Science - July 17, 2014

When looking for a meal, prehistoric people in Africa munched on the tuberous roots of weeds such as the purple nutsedge, according to a new study of hardened plaque on samples of ancient teeth. Researchers examined the dental buildup of 14 people buried at Al Khiday, an archeological site near the Nile River in central Sudan. The skeletons date back to between about 6,700 B.C., when prehistoric people relied on hunting and gathering, to agricultural times, at about the beginning of the first millennium B.C. The researchers collected samples of the individuals' dental calculus, the hardened grime that forms when plaque accumulates and mineralizes on teeth. Such buildup is fairly common in prehistoric skeletons, the researchers said.

Oldest human feces shows Neanderthals ate vegetables BBC - June 26, 2014

Analysis of the oldest reported trace of human feces has added weight to the view that Neanderthals ate vegetables. Found at a dig in Spain, the ancient excrement showed chemical traces of both meat and plant digestion. An earlier view of these early humans as purely meat-eating has already been partially discredited by plant remains found in their caves and teeth.

Did Neanderthals eat their vegetables? PhysOrg - June 25, 2014

The popular conception of the Neanderthal as a club-wielding carnivore is, well, rather primitive, according to a new study conducted at MIT. Instead, our prehistoric cousin may have had a more varied diet that, while heavy on meat, also included plant tissues, such as tubers and nuts.

Paleo diet didn't change – the climate did PhysOrg - March 19, 2014

Why were Neanderthals replaced by anatomically modern humans around 40,000 years ago? One popular hypothesis states that a broader dietary spectrum of modern humans gave them a competitive advantage on Neanderthals. Geochemical analyses of fossil bones seemed to confirm this dietary difference. Indeed, higher amounts of nitrogen heavy isotopes were found in the bones of modern humans compared to those of Neanderthals, suggesting at first that modern humans included fish in their diet while Neanderthals were focused on the meat of terrestrial large game, such as mammoth and bison.

Paleo Diet May Have Included Some Sweets, Carbs Live Science - January 6, 2014

The teeth from skeletons unearthed in the Grotte des Pigeons cave in Morocco reveal evidence of extensive tooth decay and other dental problems, likely a result of their acorn-rich diet. Ancient hunter-gatherers from the area that is now Morocco had cavities and missing teeth, a new study finds. The rotten teeth on the ancient skeletons, which date back to about 15,000 years ago, probably resulted from a carbohydrate-rich diet full of acorns. The findings show that at least some ancient populations were loading up on carbs thousands of years before the cultivation of grain took hold

Cavemen discovered recycling PhysOrg - October 11, 2013

If you thought recycling was just a modern phenomenon championed by environmentalists and concerned urbanites - think again. There is mounting evidence that hundreds of thousands of years ago, our prehistoric ancestors learned to recycle the objects they used in their daily lives. Just as today we recycle materials such as paper and plastic to manufacture new items, early hominids would collect discarded or broken tools made of flint and bone to create new utensils

'Ancient humans' used toothpicks BBC - October 8, 2013

"Ancient humans" used toothpicks nearly 1.8 million years ago, a study of their teeth has revealed. A team studied hominid jaws from the Dmanisi Republic of Georgia - the earliest evidence of primitive humans outside Africa. They also found evidence of gum disease caused by repeated use of what must have been a basic toothpick. Writing in PNAS, the team says its findings help to explain the diversity found in hominid teeth. The researchers used a new forensic approach to look at variations on the teeth of hominids thought by some to be early European ancestors. Teeth can shed light on what the individuals ate and how old they may have been, but until now it was not clear why there was so much diversity in the Georgian hominid mandibles, or jaws.

Prehistoric Europeans spiced their cooking BBC - August 22, 2013

Europeans had a taste for spicy food at least 6,000 years ago, it seems. Researchers found evidence for garlic mustard in the residues left on ancient pottery shards discovered in what is now Denmark and Germany. The spice was found alongside fat residues from meat and fish.

Prehistoric Europeans Liked Spicy Food, Study Suggests Live Science - August 22, 2013

A piece of an ancient cooking pot with some blackened foodresidue on it. The pottery shard, excavated from an archaeological site in northern Europe, is more than 6,000 years old.

Early human ancestors had more variable diet: Dietary preferences of 3 groups of hominins reconstructed PhysOrg - August 8, 2012

The latest research sheds more light on the diet and home ranges of early hominins belonging to three different genera, notably Australopithecus, Paranthropus and Homo – that were discovered at sites such as Sterkfontein, Swartkrans and Kromdraai in the Cradle of Humankind, about 50 kilometres from Johannesburg. Australopithecus existed before the other two genera evolved about 2 million years ago.

No nuts for 'Nutcracker Man': Early human relative apparently chewed grass instead PhysOrg - May 2, 2011

For decades, a 2.3 million- to 1.2 million-year-old human relative named Paranthropus boisei has been nicknamed Nutcracker Man because of his big, flat molar teeth and thick, powerful jaw. But a definitive new University of Utah study shows that Nutcracker Man didn’t eat nuts, but instead chewed grasses and possibly sedges - a discovery that upsets conventional wisdom about early humanity’s diet.

Why the switch from foraging to farming? PhysOrg - March 7, 2011

Thousands of years ago, our ancestors gave up foraging for food and took up farming, one of the most important and debated decisions in history.

Coca leaves first chewed 8,000 years ago, says research BBC - December 2, 2010

Peruvian foraging societies were already chewing coca leaves 8,000 years ago, archaeological evidence has shown. Ruins beneath house floors in the northwestern Peru showed evidence of chewed coca and calcium-rich rocks. Such rocks would have been burned to create lime, chewed with coca to release more of its active chemicals.

Prehistoric man ate flatbread 30,000 years ago: study PhysOrg - October 19, 2010

Starch grains found on grinding stones suggest that prehistoric man may have consumed a type of bread at least 30,000 years ago in Europe, US researchers said.

Fossils of earliest land plants discovered in Argentina BBC - October 12, 2010

The discovery puts back by 10 million years the colonization of land by plants, and suggests that a diversity of land plants had evolved by 472 million years ago. The newly found plants are liverworts, very simple plants that lack stems or roots.

Tool-making and meat-eating began 3.5 million years ago BBC - August 11, 2010

Researchers have found evidence that hominins - early human ancestors - used stone tools to cleave meat from animal bones more than 3.2 million years ago. That pushes back the earliest known tool use and meat-eating in such hominins by more than 800,000 years.

Human Ancestors Were Homemakers Live Science - December 18, 2009

In a stone-age version of "Iron Chef," early humans were dividing their living spaces into kitchens and work areas much earlier than previously thought, a new study found. So rather than cooking and eating in the same area where they snoozed, early humans demarcated such living quarters. Archaeologists discovered evidence of this coordinated living at a hominid site at Gesher Benot Ya‘aqov, Israel from about 800,000 years ago. Scientists aren't sure exactly who lived there, but it predates the appearance of modern humans, so it was likely a human ancestor such as Homo erectus.

Exploring the Stone Age pantry PhysOrg - December 18, 2009

The consumption of wild cereals among prehistoric hunters and gatherers appears to be far more ancient than previously thought, according to a University of Calgary archaeologist who has found the oldest example of extensive reliance on cereal and root staples in the diet of early Homo sapiens more than 100,000 years ago.

A 200,000-year-old cut of meat PhysOrg - October 15, 2009

New finds unearthed at Qesem Cave in Israel suggest that during the late Lower Paleolithic period (between 400,000 and 200,000 years ago), people hunted and shared meat differently than they did in later times. Instead of a prey's carcass being prepared by just one or two persons resulting in clear and repeated cutting marks -- the forefathers of the modern butcher cut marks on ancient animal bones suggest something else.

Diet, population size and the spread of modern humans into Europe PhysOrg - August 11, 2009

Research suggests that at least some of the European early modern humans consistently consumed fish, supplementing their diet of terrestrial animals. Accumulating carbon and nitrogen stable isotope data from fossil humans in Europe is pointing towards a significant shift in the range of animal resources exploited with the spread of modern humans into Europe 40,000 years ago.

Both the preceding Neandertals and the incoming modern humans regularly and successfully hunted large game such as deer, cattle and horses, as well as occasionally killing larger or more dangerous animals. There is little evidence for the regular eating of fish by the Neanderthals.

Early human hunters had fewer meat-sharing rituals PhysOrg - August 13, 2009

A University of Arizona anthropologist has discovered that humans living at a Paleolithic cave site in central Israel between 400,000 and 250,000 years ago were as successful at big-game hunting as were later stone-age hunters at the site, but that the earlier humans shared meat differently. The Qesem Cave people hunted cooperatively, then carried the highest quality body parts of their prey to the cave, where they cut the meat with stone blade cutting tools and cooked it with fire. "Qesem" means "surprise." The cave was discovered in hilly limestone terrain about seven miles east of Tel-Aviv not quite nine years ago, during road construction.

Neanderthals wouldn't have eaten their sprouts either PhysOrg - August 12, 2009

Spanish researchers say they're a step closer to resolving a "mystery of evolution" -- why some people like Brussels sprouts but others hate them. They have found that a gene in modern humans that makes some people dislike a bitter chemical called phenylthiocarbamide, or PTC, was also present in Neanderthals hundreds of thousands of years ago.

The scientists made the discovery after recovering and sequencing a fragment of the TAS2R38 gene taken from 48,000-year-old Neanderthal bones found at a site in El Sidron, in northern Spain

Humans Ate Fish 40,000 Years Ago Live Science - July 7, 2009

At least one of our ancestors regularly ate fish 40,000 years ago, a new study finds. Scientists analyzed chemical compositions of the protein collagen in an ancient human skeleton from Tianyuan Cave near Beijing to reach their conclusion. Fishing at this time must have involved considerable effort, the researchers think, because fossil records suggest humans were not using sophisticated tools - beyond crude stone blades - until about 50,000 years ago.

Mammals Drank Milk for Past 160 Million Years Live Science - May 12, 2009

Moms today are strongly encouraged to nurse their babies. Mother's milk is more nourishing than formula and provides infants with some immune protection. This makes intuitive sense. Mammals and milk go together - it is produced by all species in this group and apparently has been for at least 160 million years. A new study looks at the genes that produce milk among seven species of mammals, including us, and finds that all of them share a lot of the same milk-making genes but not all species deliver the same milk. In fact, the milk might be tailored to the specific immune system needs of the animals.