The Twenty-First, Twenty-Second, Twenty-Third, Twenty-Fourth, and Twenty-Fifth Dynasties of ancient Egypt are often combined under the group title, Third Intermediate Period. After the reign of Ramesses III, a long, slow decline of royal power in Egypt followed.

The pharaohs of the Twenty-First Dynasty ruled from Tanis, but were mostly active only in Lower Egypt which they controlled. This dynasty is described as 'Tanite' because its political capital was based at Tanis, a city in the north-eastern Nile delta of Egypt. It is located on the Tanitic branch of the Nile which has long since silted up.. Meanwhile, the High Priests of Amun at Thebes effectively ruled Middle and Upper Egypt in all but name. The later Egyptian Priest Manetho of Sebennytos states in his Epitome on Egyptian royal history that "the 21st Dynasty of Egypt lasted for 130 years".

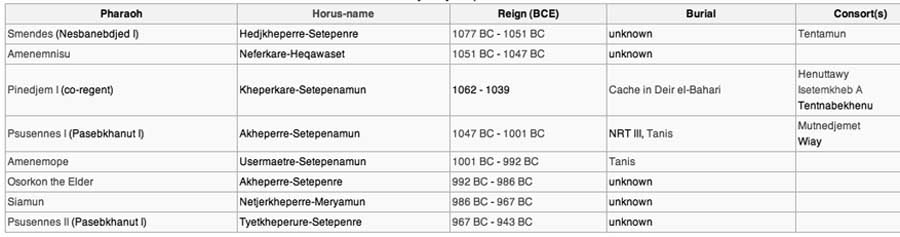

Hedjkheperre Setepenre Smendes was the founder of the Twenty-first dynasty of Egypt and succeeded to the throne after burying Ramesses XI in Lower Egypt - territory which he controlled. His Egyptian nomen or birth name was actually Nesbanebdjed meaning "He of the Ram, Lord of Mendes" but it was translated into Greek as Smendes by later classical writers such as Josephus and Sextus Africanus. While Smendes' precise origins remain a mystery, he is thought to have been a powerful governor in Lower Egypt during the Renaissance era of Ramesses XI and his base of power was Tanis.

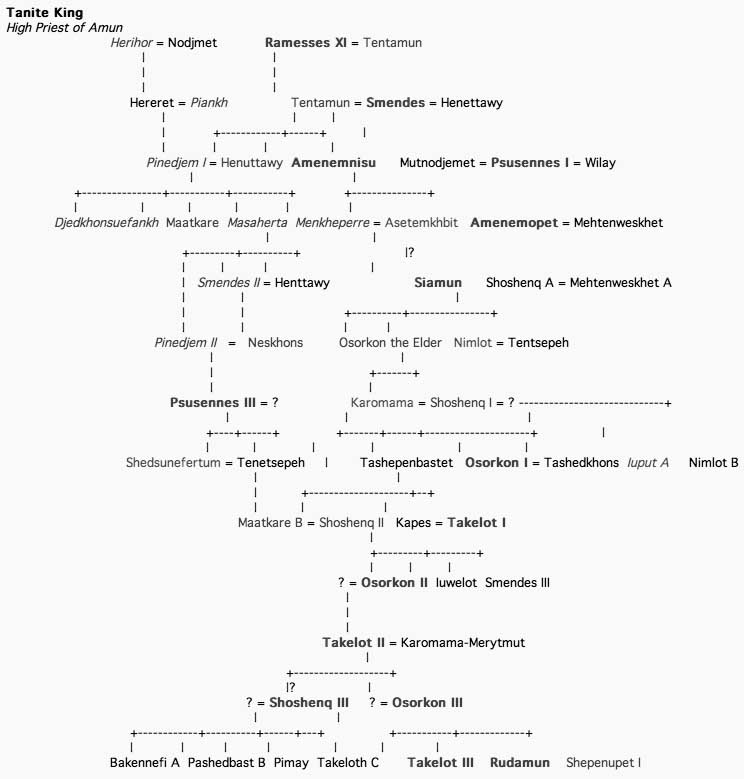

Nesibanebdjedet (Smendes) may have been a son of a lady named Hrere. Hrere was a Chief of the Harem of Amun-Re and likely the wife of a high priest of Amun. If Hrere was the mother of Nesibanebdjedet, then he was a brother of Nodjmet and through her brother in law of the High Priests Herihor and Piankh. Nesibanebdjedet (Smendes) was married to Tentamun B, likely a daughter of Ramesses IX. They may have been the parents of his successor Amenemnisu.

Smendes features prominently in the Report of Wenamun, dated to Year 5 of the Renaissance or Whm Mswt era (or Year 23 proper of Ramesses XI), as a person of the highest importance. Wenamun states here that he had to visit Tanis and personally present his letters of accreditation to Smendes in order to receive the latter's permission to travel north to modern Lebanon and procure precious cedar wood for use in the Great Temples of Amun at Thebes. Smendes responded by dispatching a ship for Wenamun's travels to Syria and the Levant.

Smendes' nominal authority over Upper Egypt is attested by a single inscribed stela found in a quarry at Ed-Dibabiya, opposite Gebelein on the right bank of the Nile as well as a separate graffito inscription on an enclosure Wall of the Temple of Monthu at Karnak dating from the reign of Tuthmose III.

The quarry stela describes how Smendes "while residing in Memphis, heard of danger to the temple of Luxor from flooding, gave orders for repairs (hence the quarry works), and received news of the success of the mission."

Smendes is assigned a reign of 26 Years by Manetho in his Epitome and was the husband of Tentamun. This figure is supported by the Year 25 date on the Banishment Stela which recounts that the High Priest Menkheperre suppressed a local revolt in Thebes in Year 25 of a king who can only be Smendes because there is no evidence that the High Priests counted their own regnal years even when they assumed royal titles like Pinedjem I did. Menkheperre then exiled the leaders of the rebellion to the Western Desert Oases. These individuals were pardoned several years later during the reign of Smendes' successor, Amenemnisu.

Smendes ruled over a divided Egypt and only effectively controlled Lower Egypt during his reign while Middle and Upper Egypt was effectively under the suzerainty of the High Priests of Amun such as Pinedjem I, Masaharta and Menkheperre. His prenomen or throne name Hedjkheperre Setepenre/Setepenamun - which means 'Bright is the Manifestation of Re, Chosen of Re/Amun' - became very popular in the following 22nd Dynasty and 23rd Dynasty. In all, five kings: Shoshenq I, Shoshenq IV, Takelot I, Takelot II and Harsiese A adopted it for their own use. On the death of Smendes in 1051 BC, he was succeeded by Neferkare Amenemnisu, who may have been this king's son.

Neferkare Amenemnisu was a pharaoh during the 21st Dynasty of ancient Egypt. His existence was only confirmed in 1940 when the tomb of his successor Psusennes I was discovered by Pierre Montet. A gold bow cap inscribed with both Amenemnisu's royal name, Neferkare, and that of his successor Psusennes I was discovered in the tomb of Psusennes I. Previously, his existence had been doubted as no objects naming him had been discovered. However, the memory of his short rule as the second pharaoh of the 21st Dynasty was preserved in Manetho's Epitome as a king Nephercheres who is assigned a short reign of 4 years. Amenemnisu's name means "Amun is King" in Egyptian.

While his reign is generally obscure, the then High Priest of Amun at Thebes, Menkheperre, is known to have pardoned several leaders of a rebellion against the High Priest's authority during Amenemnisu's reign. These rebels had previously been exiled to the Western Oasis of Egypt in Year 25 of Smendes.

Pinedjem I was the High Priest of Amun at Thebes in Ancient Egypt from 1070 BC to 1032 BC and the de facto ruler of the south of the country from 1054 BC. He was the son of the High Priest Piankh. However, many Egyptologists today believe that the succession in the Amun priesthood actually ran from Piankh to Herihor to Pinedjem I.

According to the new hypothesis, Pinedjem I was too young to succeed to the High Priesthood of Amun after the death of Piankh. Herihor instead intervened to assume to this office. After Herihor's death, Pinedjem I finally claimed this office which had once been held by his father Piankh. This interpretation is supported by the decorations from the Temple of Khonsu at Karnak where Herihor's wall reliefs here are immediatedly followed by those of Pinedjem I with no intervening phase for Piankh and also by the long career of Pinedjem I who served as High Priest of Amun and later as king at Thebes.

His parents Piankh and Nodjmet had several children; three brothers (Heqanefer, Heqamaat, Ankhefenmut) and one sister (Faienmut) of Pinedjem I are known. Three of his wives are known. Duathathor-Henuttawy, the daughter of Ramesses XI bore him several children: the future pharaoh Psusennes I, the God's Wife of Amun Maatkare, Princess Henuttawy and probably Queen Mutnedjmet, the wife of Psusennes.

Another wife was Isetemkheb, Singer of Amun. She is mentioned along with Pinedjem I on bricks found at el-Hiban. A possible third wife is Tentnabekhenu, who is mentioned on the funerary papyrus of her daughter Nauny. Nauny was buried at Thebes and is called a King's Daughter, thus it is likely that Pinedjem was her father.

Other than Psusennes, Pinedjem had four other sons, whose mother is unidentified, but one or more of them must have been born to Duathathor-Henuttawy: Masaharta, Djedkhonsuefankh, Menkheperre (all of whom became High Priests of Amun) and Nesipaneferhor, a God's Father (priest) of Amun, whose name replaced that of a son of Herihor in the Karnak temple of Khonsu.

Psusennes I, Pasibkhanu or Hor-Pasebakhaenniut I was the third king of the Twenty-first dynasty of Egypt who ruled from Tanis (Greek name for Dzann, Biblical Zoan) between 1047 - 1001 BC. Psusennes is the Greek version of his original name Pasebakhaenniut which means "The Star Appearing in the City" while his throne name, Akheperre Setepenamun, translates as "Great are the Manifestations of Ra, chosen of Amun." He was the son of Pinedjem I and Henuttawy, Rameses XI's daughter by Tentamun. He married his sister Mutnedjmet.

Psusennes I's precise reign length is unknown because different copies of Manetho's records credit him with a reign of either 41 or 46 Years. Some Egyptologists have proposed raising the 41 year figure by a decade to 51 years to more closely match certain anonymous Year 48 and Year 49 dates in Upper Egypt.

However, the German Egyptologist Karl Jansen-Winkeln has suggested that all these dates should be attributed to the serving High Priest of Amun, Menkheperra instead who is explicitly documented in a Year 48 record. Jansen-Winkeln notes that "in the first half of Dyn. 21, HP Herihor, Pinedjem I and Menkheperra have royal attributes and [royal] titles to differing extents" whereas the first three Tanite kings (Smendes aka: Nesubanebded, Amenemnisu and Psusennes I) are almost never referred to by name in Upper Egypt with the exception of one graffito and rock stela for Smendes.

In contrast, the name of Psusennes I's Dynasty 21 successors such as Amenemope, Osochor, and Siamun appear frequently in various documents from Upper Egypt while the Theban High Priest Pinedjem II who was a contemporary of the latter three kings never adopted any royal attributes or titles in his career.

Hence, two separate Year 49 dates from Thebes and Kom Ombo could be attributed to the ruling High Priest Menkheperra in Thebes instead of Psusennes I but this remains uncertain. Psusennes I's reign has been estimated at 46 years by the editors of the Handbook to Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Psusennes I must have enjoyed cordial relations with the serving High Priests of Amun in Thebes during his long reign since the High Priest Smendes II donated several grave goods to this king which was found in Psusennes II's tomb.

During his long reign, Psusennes built the enclosure walls and the central part of the Great Temple at Tanis which was dedicated to the triad of Amun, Mut and Khonsu.

Tomb

Silver anthropoid coffin of Psusennes I, Cairo Museum

Gold and lapis lazuli collar of Psusennes I, Cairo Museum

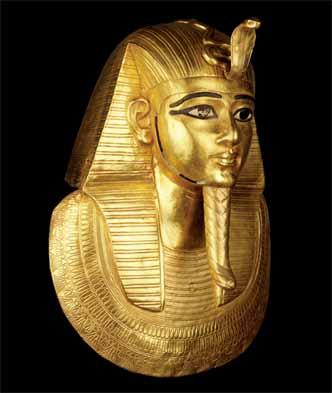

Funeral Mask

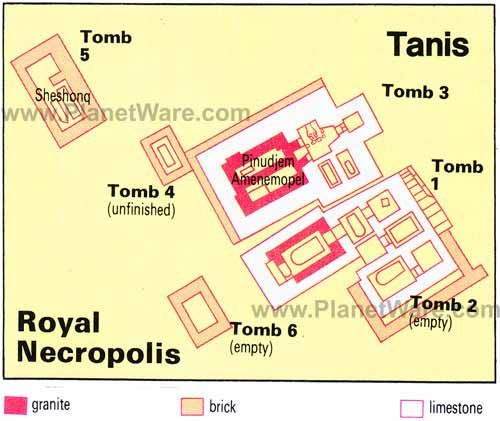

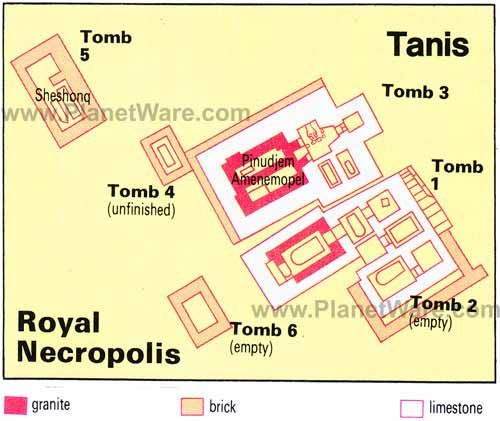

Professor Pierre Montet discovered pharaoh Psusennes I's intact tomb (No.3 or NRT III) in Tanis in 1940. Unfortunately, due to its moist Lower Egypt location, most of the "perishable" wood objects were destroyed by water - a fate not shared by KV62, the tomb of Tutankhamun in the drier climate of Upper Egypt. However, the king's magnificent funerary mask was recovered intact; it proved to be made of gold and lapis lazuli and held inlays of black and white glass for the eyes and eyebrows of the object.

Psusennes I's mask is considered to be "one of the masterpieces of the treasures of Tanis" and is currently housed in Room 2 of the Cairo Museum. It has a maximum width and height of 38 cm and 48 cm respectively. The pharaoh's "fingers and toes had been encased in gold stalls, and he was buried with gold sandals on his feet. The finger stalls are the most elaborate ever found, with sculpted fingernails. Each finger wore an elaborate ring of gold and lapis lazuli or some other semiprecious stone."

Psusennes I's outer and middle sarcophagi had been recycled from previous burials in the Valley of the Kings through the state-sanctioned tomb-robbing that was common practice in the Third Intermediate Period. A cartouche on the red outer sarcophagus shows that it had originally been made for Pharaoh Merenptah, the nineteenth dynasty successor of Ramesses II. Psusennes I, himself, was interred in an "inner silver coffin" which was inlaid with gold. Since "silver was considerably rarer in Egypt than gold," Psusennes I's silver "coffin represents a sumptuous burial of great wealth during Egypt's declining years." He was placed in a silver casket instead of golden because it is learnt that Psusennes I preferred silver to gold.

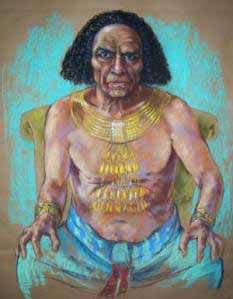

Dr. Douglass Derry, who worked as the head of Cairo University's Anatomy Department, examined the king's remains in 1940, determined that the king was an old man when he died. Derry noted that Psusennes I's teeth were badly worn and full of cavities, and observed that the king suffered from extensive arthritis and was probably crippled by this condition in his final years.

There are two interesting things about Psusennes I. First, he ruled his part of the kingdom longer than any other Pharaoh had done. Second, his tomb was found intact and there were no signs of breach into the tomb. Many robbers had dug up the adjacent graves lying in the neighborhood but never touched Psusennes I tomb. When the tomb was discovered the Second World War made the world divert their interest elsewhere. It was only in the later years of 90's and early 2000's that Egyptologists started returning to the Nile delta and researching the tomb of Pseusennes I. Medical studies on the body of Psusennes I revealed that he had been suffering from teeth and back problems which caused him a lot of pain in his last years.

Pharaoh Amenemope (prenomen: UsirmaatRa) was the son of Psusennes I. Amenemope/Amenemopet's birth name or nomen translates as "Amun in the Opet Feast." He served as a junior co-regent at the end of his father's final years according to the evidence from a mummy bandage fragment. All surviving versions of his Manetho's Epitome state that Amenemopet enjoyed a reign of 9 years.

Both Psusennes I and Amenemopet's royal tombs were discovered intact by the French Egyptologist Pierre Montet in his excavation at Tanis in 1940 and were filled with significant treasures including gold funerary masks, coffins and numerous other items of precious jewelry. Montet opened Amenemopet's tomb in April 1940, just a month before the German invasion of France and the Low Countries in World War II. Thereafter, all excavation work abruptly ceased until the end of the war. Montet resumed his excavation work at Tanis in 1946 and later published his findings in 1958.

The Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen states that there are few known monuments of Amenemopet. His tomb at Tanis was barely 20 feet long by 12-15 feet wide, "a mere cell compared with the tomb of Psusennes I" while his only other original projects was to continue with the decoration of the chapel of Isis "Mistress of the Pyramids at Giza" and to make an addition to one of the temples in Memphis. Amenemope was served by two High Priests of Amun at Thebes - Smendes II (briefly) and then by Pinodjem II, Smendes' brother.

Kitchen observes that in Thebes, his authority as king was undisputed - no less than nine burials of the Theban clergy had braces, pendants or bandages inscribed with the name of Amenemope as pharaoh and of Pinedjem as pontiff. Pen-nest-tawy, captain of the barge of Amun in Thebes, possessed a Book of the Dead dated to Year 5 of this king's reign.

In the introduction to the third (1996) edition of his book on The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (TIPE), Kitchen notes that Papyrus Brooklyn 16.205 which mentions "a Year 49 followed by a Year 4 must now be attributed to the time of Psusennes I and Amenemope, and not to the discovery of a new Tanite king named Sheshonk IV who ruled for a minimum of 10 years between Year 39 of Shashank III and Year 1 of Pami. Consequently, the creation of this papyrus document must be dated to Year 4 of king Amenemope. There is also reason to believe that the 21st Dynasty Pharaoh known as Amenemnisu may be one and the same king as Amenemope.

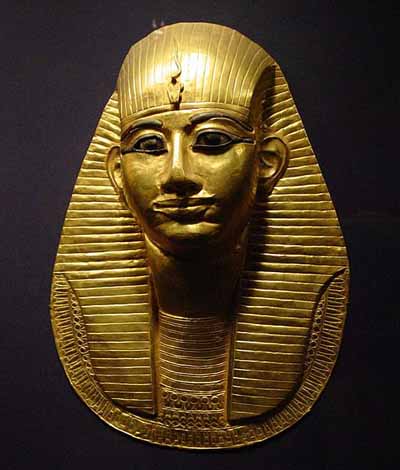

Four objects from king Amenemopet's royal tomb preserve the name of his illustrious father Psusennes I including a collar and several bracelets. His funerary mask, now located in Egypt's Cairo Museum, renders a youthful depiction of the king. Unlike Psusennes I, Amenemope was buried with much less opulence since "his wooden coffins were covered with gold leaf instead of being of solid silver" while "he wore a gilt mask rather than one of solid gold." He was later reburied in the tomb of his father Psusennes I during the reign of king Siamun.

Akheperre Setepenre Osorkon the Elder was the fifth king of the twenty-first dynasty of Egypt and was the first pharaoh of Libyan extraction in Egypt. He is also sometimes known as "Osochor," following Manetho's Aegyptiaca.

Osorkon the Elder was the son of Shoshenq, the Great Chief of the Ma by the latter's wife 'Mehtenweskhet who is given the prestigious title of 'King's Mother' in a document. Osochor was the brother of Nimlot A, the Great Chief of the Ma, and Tentshepeh A the daughter of the Great Chief of the Ma and, thus, an uncle of Shoshenq I, founder of the Twenty-second Dynasty.

His existence was doubted by most scholars until Eric Young established in 1963 that the induction of a temple priest named Nespaneferhor in Year 2 I Shemu day 20 under a certain king named Akheperre Setepenre - in fragment 3B, line 1-3 of the Karnak Priest Annals - occurred one generation prior to the induction of Hori, Nespaneferhor's son in Year 17 of Siamun, which is also recorded in the same annals. Young argued that this king Akheperre Setepenre was the unknown Osochor. This hypothesis was not fully accepted by all Egyptologists at that time, however.

But in a 1976-1977 paper, Jean Yoyotte noted that a Libyan king named Osorkon was the son of Shoshenq A by the Lady Mehtenweshkhet, with Mehtenweshkhet being explicitly titled the "King's Mother" in a certain genealogical document. Since none of the other kings named Osorkon had a mother named Mehtenweshkhet, it was conclusively established that Akheperre Setepenre was indeed Manetho's Osochor, whose mother was Mehtenweshkhet. The Lady Mehtenweshet A was also the mother of Nimlot A, Great Chief of the Meshwesh and, thus, Shoshenq I's grandmother.

Based on a calculation of the aforementioned Year 2 lunar date of this king - which Rolf Krauss in an astronomical calculation has shown to correspond to 990 BC - Osochor must have become king 2 years before the induction of Nespaneferhor in 992 BC.

Osorkon the Elder's reign is significant because it foreshadows the coming the Libyan Twenty-second dynasty. He is credited with a reign of six years in Manetho's Aegyptiaca and was succeeded in power by Siamun, who was either Osochor's son or an unrelated native Egyptian.

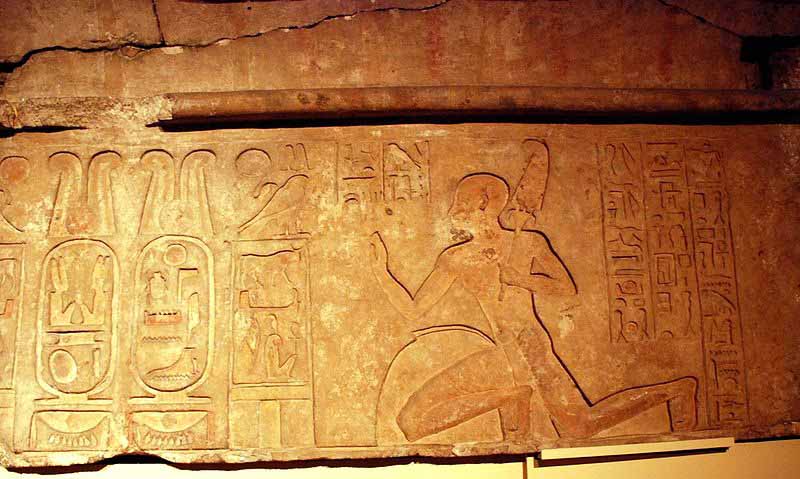

Ankhefenmut adores the royal name of pharaoh Siamun in this doorway lintel.

Neterkheperre or Netjerkheperre-setepenamun Siamun was the sixth pharaoh of Egypt during the Twenty-first dynasty. He built extensively in Lower Egypt for a king of the Third Intermediate Period and is regarded as one of the most powerful rulers of this Dynasty after Psusennes I. Siamun's prenomen, Netjerkheperre-Setepenamun, means "Like a God is The Manifestation of Re, Chosen of Amun" while his name means 'son of Amun.

Siamun was erroneously credited with a reign of only 9 Years by Manetho, a figure which is now universally amended to 19 Years by all scholars on the basis of a Year 17 the first month of Shemu day lost inscription in fragment 3B, lines 3-5 dated to pharaoh Siamun from the Karnak Priestly Annals.

It records the induction of Hori, son of Nespaneferhor into the Priesthood at Karnak. This date was a lunar Tepi Shemu feast day. Based on the calculation of this lunar Tepi Shemu feast, Year 17 of Siamun has been shown by the German Egyptologist Rolf Krauss to be equivalent to 970 BC. Hence, Siamun would have taken the throne about 16 years earlier in 986 BC. A stela dated to Siamun's Year 16 records a land-sale between some minor priests of Ptah at Memphis.

The Year 17 inscription is an important palaeographical development because it is the first time in Egyptian recorded history that the word pharaoh was employed as a title and linked directly to a king's royal name: as in Pharaoh Siamun here. Henceforth, references to Pharaoh Psusennes II (Siamun's successor), Pharaoh Shoshenq I, Pharaoh Osorkon I, and so forth become commonplace. Prior to Siamun's reign and all throughout the Middle and New Kingdom, the word pharaoh referred only to the office of the king.

According to the French Egyptologist Nicolas Grimal, Siamun doubled the size of the Temple of Amun at Tanis and initiated various works at the Temple of Horus at Mesen. He also built at Heliopolis and at Piramesse where a surviving stone block bears his name. Siamun constructed and dedicated a new temple to Amun at Memphis with 6 stone columns and doorways which bears his royal name.

Finally, he bestowed numerous favors onto the Memphite Priests of Ptah. In Upper Egypt, he generally appears eponymously on a few Theban monuments although Siamun's High Priest of Amun at Thebes, Pinedjem II, organised the removal and re-burial of the New Kingdom royal mummies from the Valley of the Kings in several hidden mummy caches at Deir El-Bahari Tomb DB320 for protection from looting. These activities are dated from Year 1 to Year 10 of Siamun's reign.

One fragmentary but well known surviving triumphal relief scene from the Temple of Amun at Tanis depicts an Egyptian pharaoh smiting his enemies with a mace. The king's name is explicitly given as Neterkheperre Setepenamun) Siamun, beloved of Amun in the relief and there can be no doubt that this person was Siamun as the eminent British Egyptologist, Kenneth Kitchen stresses in his book, On the Reliability of the Old Testament.

Siamun appears here "in typical pose brandishing a mace to strike down prisoners now lost at the right except for two arms and hands, one of which grasps a remarkable double-bladed ax by its socket." The writer observes that this double bladed axe or 'halbread' has a flared crescent shaped blade which is close in form to the Aegean influenced double axe but is quite distinct from the Palestinian/Canaanite double headed axe which has a different shape that resembles an X.

Thus, Kitchen concludes Siamun's foes were the Philistines who were descendants of the Aegean based Sea Peoples and that Siamun was commemorating his recent victory over them at Gezer by depicting himself in a formal battle scene relief at the Temple in Tanis. More recently Paul S Ash has put forward a detailed argument that Siamun's relief portrays a fictitious battle. He points out that in Egyptian reliefs Philistines are never shown holding an axe, and that there is no archaeological evidence for Philistines using axes. He also argues that there is nothing in the relief to connect it with Philistia or the Levant.

Under Siamun, Egypt embarked upon an active foreign policy and he is most probably the Pharaoh who formed an alliance with the new ruler of Israel, King Solomon against the Philistines. Solomon, the son of David, had just assumed power around 971 or 970 BC which was certainly around the middle of Siamun's reign. As part of the arrangements within this Egyptian-Israelite alliance, the Egyptian king attacked and laid waste the Philistine city of Gezer in part to safeguard Egypt's commercial ties with Phoenicia - something which the Philistines were threatening - and also to take advantage of the Philistines' momentary weakness after King David's series of Biblical wars against their state. Solomon, for his part, was then permitted to permanently secure his kingdom's southern borders by occupying Gezer, which henceforth, remained a part of Ancient Israel. The alliance was consecrated by a royal marriage between Solomon and a daughter of the Egyptian king.

The only mention in the Bible of a Pharaoh who might be Siamun is "Pharaoh King of Egypt had come up and captured Gezer; he destroyed it by fire, killed the Canaanites who dwelt in the town, and gave it as dowry to his daughter, Solomon's wife. As shown above, Kenneth Kitchen believes that Siamun conquered Gezer and gave it to Solomon. Others such as Paul S. Ash and Mark W. Chavalas disagree, and Chavalas states that "it is impossible to conclude which Egyptian monarch ruled concurrently with David and Solomon".

Professor Edward Lipinski argues that Gezer, then unfortified, was destroyed late in the 10th century (and thus not contemporary with Solomon) and that the most likely Pharaoh was Shoshenq I. "The attempt at relating the destruction of Gezer to the hypothetical relationship between Siamun and Solomon cannot be justified factually, since Siamun's death precedes Solomon's accession."

Although Siamun's original royal tomb has never been located, scholars believe that he is one of "two completely decayed mummies in the antechamber of NRT-III (Psusennes I's tomb)" on the basis of ushabtis found on them which bore this king's name. Siamun's original tomb may have been inundated by the Nile which compelled a reburial of this king in Psusennes I's tomb.

Titkheperure or Tyetkheperre Psusennes II or Hor-Pasebakhaenniut II, was the last king of the Twenty-first dynasty of Egypt. His royal name means "Image of the transformation of Re" in Egyptian. Psusennes II is often considered the same person as the High-Priest of Amun known as Psusennes III.

The Egyptologist Karl Jansen-Winkeln notes that an important graffito from the Temple of Abydos contains the complete titles of a king Tyetkheperre Setepenre Pasebakhaenniut Meryamun "who is simultaneously called the HPA (ie. High Priest of Amun) and supreme military commander.. This suggests that Psusennes was both king at Tanis and the High Priest in Thebes at the same time meaning he did not resign his office as High Priest of Amun during his reign.

The few contemporary attestations from his reign include the aforementioned graffito in Seti I's Abydos temple, an ostracon from Umm el-Qa'ab, an affiliation at Karnak and his presumed burial - which consists of a gilded coffin with a royal uraeus and a Mummy, found in an antechamber of Psusennes I's tomb at Tanis. He was a High Priest of Amun at Thebes and the son of Pinedjem II and Istemkheb. His daughter Maatkare was the Great Royal Wife of Osorkon I.

Items which can be added to this list include a Year 5 Mummy linen that was written with the High Priest Psusennes III's name. It is generally assumed that a Year 13 III Peret 10+X date in fragment 3B, line 6 of the Karnak Priestly Annals belongs to his reign.

Unfortunately, the king's name is not stated and the only thing which is certain is that the fragment must be dated after Siamun's reign whose Year 17 is mentioned in lines 3-5. Hence, it belongs to either Psusennes II or possibly Shoshenq I's reign. More impressive are the number of objects which associate Psusennes II together with his successor, Shoshenq I, such as an old statue of Thutmose III which contains two parallel columns of texts - one referring to Psusennes II and the other to Shoshenq I - a recently unearthed block from Tell Basta which preserves the nomen of Shoshenq I together with the prenomen of Psusennes II, and a now lost graffito from Theban Tomb 18.

Recently, the first conclusive date for king Psusennes II was revealed in a newly published priestly annal stone block. This document, which has been designated as 'Block Karnak 94, CL 2149,' records the induction of a priest named Nesankhefenmaat into the chapel of Amun-Re within the Karnak precinct in Year 11 the first month of Shemu day 13 of a king named Psusennes.

The preceding line of this document recorded the induction of Nesankhefenmaat's father, a certain Nesamun, into the priesthood of Amun-Re in king Siamun's reign. Siamun was the predecessor of Psusennes II at Tanis. The identification of the aforementioned Psusennes with Psusennes II is certain since the same fragmentary annal document next records - in the following lin - the induction of Hor, the son of Nesankhefenmaat, into the priesthood of the chapel of Amun-Re at Karnak in Year 3 the second month of Akhet day 14 of king Osorkon I's reign just one generation later with Shoshenq I's 21 year reign being skipped over. This would not be unexpected since most Egyptologists believe that a generation in Egyptian society lasted a minimum of 25 years and a maximum of 30 years. Therefore, the Year 11 date can only be assigned to Psusennes II and constitutes the first securely attested date for this pharaoh's reign.

Unlike his immediate predecessor and successor - Siamun and Shoshenq I respectively - Psusennes II is generally less well attested in contemporary historical records even though various versions of Manetho's Epitome credits him with either a 14 or a 35 year reign, (generally amended to 15 years by most scholars including the British Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen).

However, the German scholar Rolf Krauss has recently argued that Psusennes II's reign was 24 years rather than Manetho's original figure of 14 years. This is based on personal information recorded in the Large Dakhla stela which dates to Year 5 of Shoshenq I; the stela preserves a reference to a land-register from Year 19 of a 'Pharaoh Psusennes'. However, since this document was composed under Shoshenq I, the use of the title Pharaoh before Psusennes here cannot establish whether the king was Psusennes I or II.

In Year 5 of Shoshenq I, this king and the founder of the 22nd Dynasty, dispatched a certain Ma (i.e. Libyan) subordinate named Wayheset to the desert oasis town of Dakhla in order to restore Shoshenq I's authority over the western oasis region of Upper Egypt. Wayheset's titles include Prince and Governor of the Oasis. His activities are recorded in the Large Dakhla stela.

This stela states that Wayheset adjudicated in a certain water dispute by consulting a land-register which is explicitly dated to Year 19 of a "Pharaoh Psusennes" in order to determine the water rights of a man named Nysu-Bastet.

Kitchen notes that this individual made an appeal to the Year 19 cadastral land-register of king Psusennes which belonged to his mother which historians assumed was made some "80 years" ago during the reign of Psusennes I.

The land register recorded that certain water rights were formerly owned by Nysu-Bastet's mother Tewhunet in Year 19 of a king Psusennes. This ruler was generally assumed by Egyptologists to be Psusennes I rather than Psusennes II since the latter's reign was believed to have lasted only 14-15 years. Based on the land register evidence, Wayheset ordered that these watering rights should now be granted to Nysu-Bastet himself.

However, if the oracle dated to Year 19 of Psusennes I as many scholars traditionally assumed, Nysu-Bastet would have been separated from his mother by a total of 80 years from this date into Year 5 of Shoshenq I - a figure which is highly unlikely since Nysu-Bastet would not have waited until extreme old age to uphold his mother's watering rights. This implies that the aforementioned king Psusennes here must be identified with Psusennes II instead - Shoshenq I's immediate predecessor and, more significantly, that Psusennes II enjoyed a minimum reign of 19 years.

The term "mother" in ancient Egypt could also be an allusion to an ancestress, the matriarch of a lineage whereby Nysu-Bastet may have been petitioning for his hereditary water rights that belonged to his grandmother, whose family name was Tewhunet. However, this argument does not account for the use of Pharaoh as a title in the Dakhla stela - a literary device which first occurs late during the reign of Siamun, an Egyptian king who ruled between 45 to 64 years after Year 19 of Psusennes I.

The most significant component of the Great Dakhla stela is its paleography. The use of the title Pharaoh Psusennes. A scholar named Helen Jacquet-Gordon believed in the 1970s that the large Dakhla stela belonged to Shoshenq III's reign due to its use of the title 'Pharaoh' directly with the ruling king's birth name = ie. "Pharaoh Shoshenq" - which was an important paleographical development in Egyptian history.

Throughout the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms of Ancient Egypt, the word pharaoh was never employed as a title such as Mr. and Mrs. or attached to a king's name such as Pharaoh Ramesses or Pharaoh Amenhotep; instead, the word pr-'3 or pharaoh was used as a noun to refer to the activities of the king (i.e., it was "Pharaoh" who ordered the creation of a temple or statue, or the digging of a well, etc.).

Rolf Krauss aptly observes that the earliest attested use of the word pharaoh as a title is documented in Year 17 of the 21st Dynasty king Siamun from Karnak Priestly Annals fragment 3B while a second use of the title Pharaoh + birth name occurs during Psusennes II's reign where a hieratic graffito in the Ptah chapel of the Abydos temple of Seti I explicitly refers to Psusennes II as the "High Priest of Amen-Re, King of the Gods, the Leader, Pharaoh Psusennes."

Consequently, the practice of attaching the title pr-'3 or pharaoh with a king's royal birth name had already started prior to the beginning of Shoshenq I's reign, let alone Shoshenq III. Hence, the Shoshenq mentioned in the large Year 5 Dakhla stela must have been Shoshenq I while the Psusennes mentioned in the same document likewise can only be Psusennes II which means that only 5 years (or 10 years if Psusennes II ruled Egypt for 24 years) would separate Nysu-Bastet from his mother.

The additional fact that the Large Dakhla stela contains a Year 5 IV Peret day 25 lunar date has helped date the aforementioned king Shoshenq's accession to 943 BC and demonstrates that the ruler here must be Shoshenq I, not Shoshenq III who ruled a century later. Helen Jacquet-Gordon did not know of the two prior examples pertaining to Siamun and Psusennes II.

The editors of the recent 2006 book on titled 'Handbook on Ancient Egyptian Chronology' - Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss and David Warburton - accept this logical reasoning and have amended Manetho's original figure of 14 years for Psusennes II to 24 years instead to Psusennes II.

This is not unprecedented since previous Egyptologists had previously amended the reign of Siamun by a decade from 9 years - as preserved in surviving copies of Manetho's Epitome - to 19 years based on certain Year 16 and Year 17 dates attested for the latter.

Psusennes II ruled Egypt for a minimum of 19 years based on the internal chronology of the Large Dakhla stela. However, a calculation of a lunar Tepi Shemu feast which records the induction of Hori son of Nespaneferhor into the Amun priesthood in regnal year 17 of Siamun, Psusennes II's predecessor - demonstrates that this date was equivalent to 970 BC. Since Siamun enjoyed a reign of 19 years, he would have died 2 years later in 968/967 BC and been succeeded by Psusennes II by 967 BC at the latest. Consequently, a reign of 24 years or 967-943 BC is now likely for Psusennes II; hence, his reign has been raised from 14 to 24 years.

Psusennes II's royal name has been found associated with his successor, Shoshenq I in a graffito from tomb TT18, and in an ostracon from Umm el-Qa'ab.