What is known of Inca religious beliefs is based on archaeological interpretation and mythology passed down to the Incas - then the Spanish. As with all ancient civilizations - there were different gods for different purposes - as created by the same algorithm and storylines in the simulation of reality through which we experience and learn.

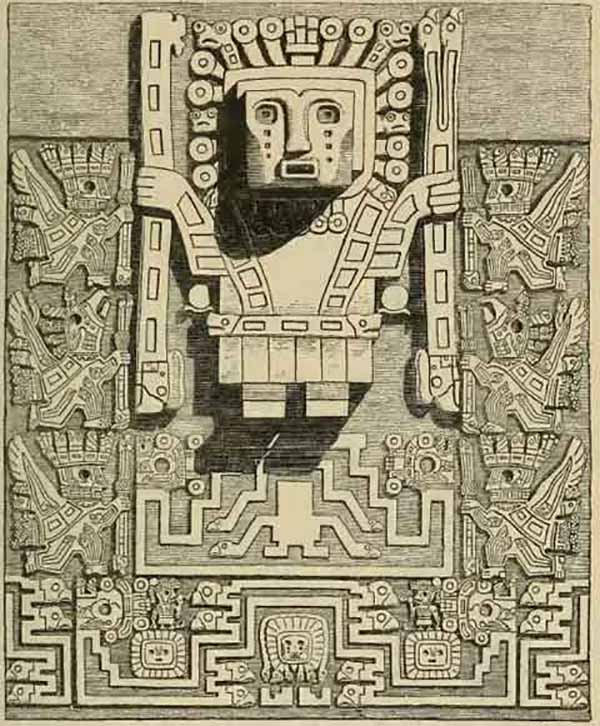

One of the most important Inca Gods was Viracocha - who also played the role of Quetzalcoatl in Aztec mythology, Kukulkan in Maya mythology, among other persona in different civilizations across the world.

He is often described as a slim white skinned bearded man with piercing blue eyes, wearing long white robes.

He sometimes carries a rod, staff, or stave used for communication, teleportation, time travel and more.

He is sometimes accompanied by a female god and/or a symbolic animal.

Is there a shape-shifting extraterrestrial component? Yes. Aliens are artificial intelligence that created the human experiment in different forms to study emotions.

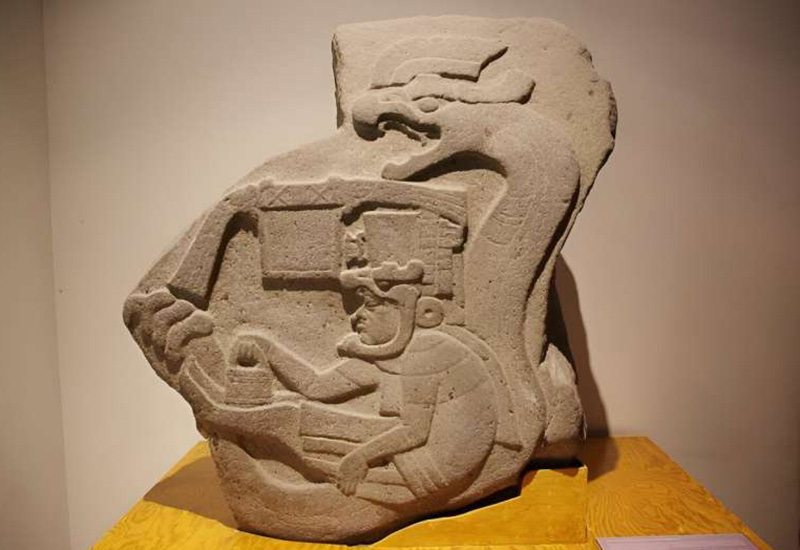

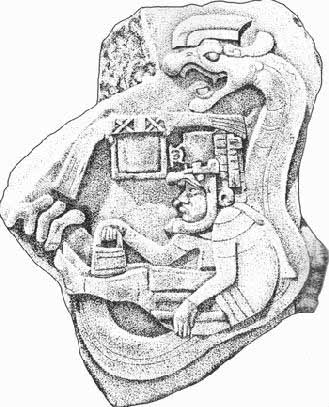

Fetus - Snake (DNA) - Chromosomes - Biogenetic Experiment Called Humans

Gods With Buckets - Bloodlines - Human Biogenetic Experiment

Viracocha is depicted by a water symbol that of the serpent or snake. This is not unlike other myths which mention amphibious gods who came from the heavens, went into the sea (collective unconscious or grids), then moved onto the land (physical reality) and created a biogenetic experiment called Humans.

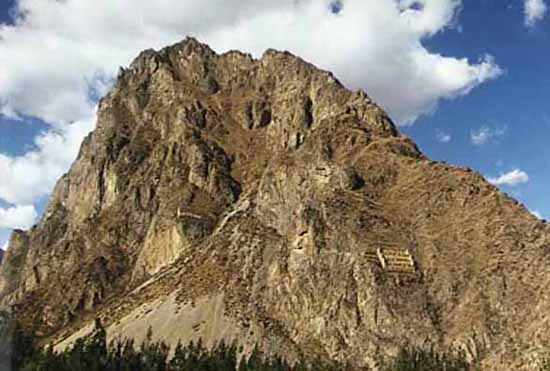

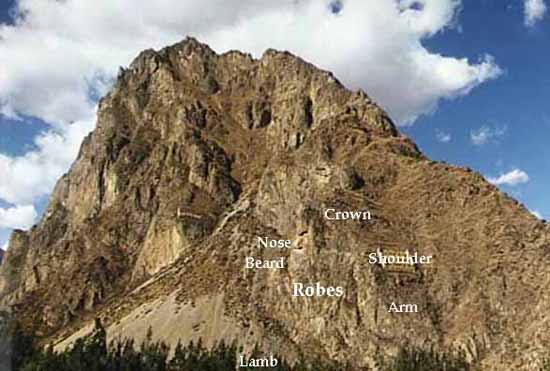

Across from the ruins of Ollantaytambo in the Urubamba Valley stands a sacred mountain believed to have the profile of Viracocha carved into the stone.

When the sun strikes this profile of Viracocha during the winter solstice, the mineral content of the mountain reflects and refracts the rays. The Inca believed that this was a sign verifying the deity of Viracocha. The solstices were sacred days for the Inca since so much of their culture was based on planting seasons. The buildings to the right and to the left were constructed by the Inca to store corn as food for winters and as offerings to Viracocha.

Apu Inti (Sun God)

Originally acknowledged by Manco Capac, the first Inca, Apu Inti became the keystone in the Incan pantheon of earth-oriented deities. He was the most magnificent creation of Viracocha and the mythological father of the royal Inca line (proposed by Manco Capac, one may surmise, to achieve a status of heavenly mandate). Honored in an array of temples spanning the empire, Apu Inti was worshipped with sacrifice (animal and human) and prayers to golden idols. Ceremonies were conducted in his praise at sunrise and sunset, with fear sweeping the empire during solar eclipses. The Incas, receiving his gift of light and life, referred to themselves as children of the sun.

Manco Capac is sometimes referred to in legend as the Mythical Father of the Incas. According to the most frequently told story, four brothers, Manco Capac, Ayar Anca, Ayar Cachi, and Ayar Uchu, and their four sisters, Mama Ocllo, Mama Huaco, Mama Cura (or Ipacura), and Mama Raua, lived at Paccari-Tampu [tavern of the dawn], several miles distant from Cuzco. They gathered together the tribes of their locality, marched on the Cuzco Valley, and conquered the tribes living there. Manco Capac had by his sister-wife, Mama Ocllo, a son called Sinchi Roca (or Cinchi Roca).

Authorities concede that the first Inca chief to be a historical figure was called Sinchi Roca (c.1105 - 1140). Thus the foundation for an empire was laid. Another legend relates that the Sun created a man and a woman on an island in Lake Titicaca. They were given a golden staff by the Sun, their father, who bade them settle permanently at whatever place the staff should sink into the earth. At a hill overlooking the present city of Cuzco the staff of gold disappeared into the earth. They gathered around them a great many people and founded the city of Cuzco and the Inca state.

Second only to Apu Inti, Chiqui Illapa was a magnanimous figure in Incan lore. Hailing rain down from the celestial river (the Milky Way), Illapa fed the empire. Incan legend asserts that he would crack his sister's water jug with a slingshot, reverberating the echoes of thunder as aqueous elixir spilled forth from the sky, showering the parched lands below. He was associated with Keypachu, the upper kingdom of heaven, and was worshipped throughout the growing season. Interestingly, any male child born during a thunderstorm was declared a priest of Chiqui Illapa, an exalted position in Incan society and within the priestly class itself.

First acknowledged by Inca Yapanqui, successor of Manco Capac, Mamaquilla was wife of the sun and timekeeper of the heavens. As the Incan calendar revolved around the lunar month, she was critical to the maintenance of a calendrical system that would ensure proper adherence to planting and harvesting seasons. She was represented with idols of silver, complementing the gold of her luminary husband.

Yakumama was believed to control subterranean and mountain streams, blessing the fields with nourishment and springing fresh water from the earth. The complement of Chiqui Illapa, she was associated with ukupacha, the lower kingdom of heaven.

A regional deity, Mamacocha was important to ayllus of the Peruvian coast, where she maintained the fertility of the sea. She was honored with conch shells, which were more valuable in this region than gold or silver.

Pachakama was also a regional deity, important to the Andean highlanders. She was ascribed the role of ensuring the fertility of soil and seed in the harsh mountain climates. When the Incas consolidated the conquest of the coastal cultures of Peru at the end of the 15th century, they didn't try to replace the god Pachacamac or destroy the temple of Pachacamac; but rather they incorporated the God Pachacamac into the Inca religion and embellished this temple, making it even more popular during the Inca period.

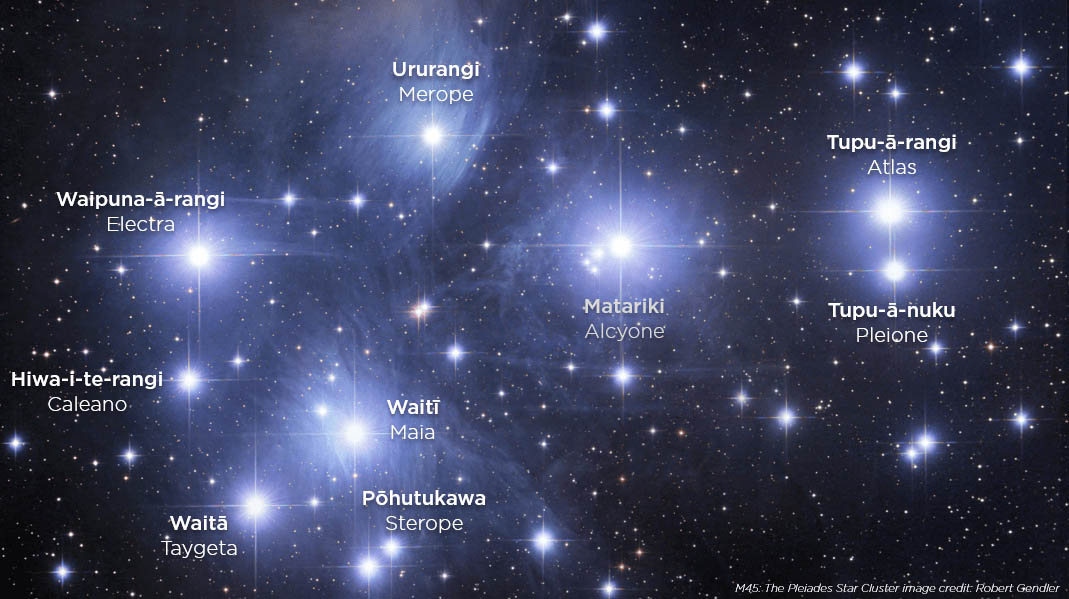

In the tradition of celestial deities, stars were thought to possess spirits that breathed life into earthly beings. Several constellations were also recognized as bearing agricultural import, such as the Pleiades, the "Seven Sisters" who preserved the seed, and the "Great Lizard", who appeared in the west during planting season and buried his head in the east at harvest time.

Waca were the family gods, or, synonymously, the shrines in which the family gods were worshipped. They were honored with more regularity than any deity of the state-recognized pantheon, as they wielded direct control over the prosperity of the ayllu. Wacas took a variety of forms, the most common being mountains, streams, caves, trees, or roads. Idols appropriate to their form were worshipped on a daily basis to appease them and avert the evocation of malevolence. Curiously, oddities such as twins, abnormal plants, and disfigured animals were also considered Wacas. In addition to the Waca of the kin group, individuals also had a personal guarding spirit of similar significance.