The Roman Emperor was the ruler of the Roman State during the imperial period (starting at about 27 BC). The Romans had no single term for the office although at any given time, a given title was associated with the emperor. If a man was "proclaimed emperor" this normally meant he was proclaimed augustus, or (for generals) imperator (from which English emperor ultimately derives). Several other titles and offices were regularly accumulated by emperors, such as caesar, princeps senatus, consul and Pontifex Maximus. The power of emperors was generally based on the accumulation of powers from republican offices and the support of the army.

Roman emperors refused to be considered "kings", instead claiming to be leaders of a republic, however nominal. The first emperor, Augustus, resolutely refused recognition as a monarch. Although Augustus could claim that his power was authentically Republican, his successor, Tiberius, could not convincingly make the same claim. Nonetheless, the Republican institutional framework (senate, consuls, magistracies etc.) was preserved until the very end of the Western Empire.

By the time of Diocletian, emperors were openly "monarchs", but the contrast with "kings" was maintained: Although the imperial succession was, de facto, generally hereditary, it was only hereditary if there was a suitable candidate acceptable to the army and the bureaucracy so the principle of automatic inheritance was not adopted. The Eastern (Byzantine) emperors ultimately adopted the formal title of Basileus, which had meant king in Greek, but became a title reserved solely for the "Roman" emperor (and the ruler of the Sassanid Empire). Other kings were referred to as regas.

In addition to their pontifical office, emperors were given divine status: initially after their death, but later from their accession. As Christianity prevailed over paganism, the emperor's religious status changed to that of Christ's regent on earth, and the Empire's status was seen as part of God's plan to Christianize the world.

The Western Roman Empire was dealt fatal blows by a set of military coups d'etat in the Italian Peninsula in 475 and 476. The division of the empire into Western and Eastern was formally abolished as a separate entity by Emperor Zeno after the death of the last Western Emperor Julius Nepos in 480. Zeno's successors ruled from Constantinople (modern Istanbul) through the conquest of that city by the Ottoman Turks in 1453. The last Roman Emperor, Constantine XI died in hand to hand combat defending the capital. A dynasty of claimants maintained the Imperial tradition in the province of Chaldia through its conquest by the Ottomans in 1461.

Rome used no single constitutional office, title or rank exactly equivalent to the English title "Roman emperor". Romans of the Imperial era used several titles to denote their emperors, and all were associated with the pre-Imperial, Republican era. "Roman emperor" is a convenient shorthand used by historians to express the complex nature of the person otherwise known as princeps - itself a republican honorific.

The emperor's legal authority derived from an extraordinary concentration of individual powers and offices extant in the Republic rather than from a new political office; emperors were regularly elected to the offices of consul and censor. Among their permanent privileges were the traditional Republican title of princeps senatus (leader of the Senate) and the religious office of pontifex maximus (chief priest of Roman state). Every emperor held the latter office and title until Gratian surrendered it in 382 AD to St. Siricius; it eventually became an auxiliary honor of the Bishop of Rome.

These titles and offices conferred great personal prestige (dignitas) but the basis of an emperor's powers derived from his auctoritas: this assumed his greater powers of command (imperium maius) and tribunician power (tribunicia potestas) as personal qualities, independent of his public office. As a result, he formally outranked provincial governors and ordinary magistrates. He had the right to enact or revoke sentences of capital punishment, was owed the obedience of private citizens (privati) and by the terms of the ius auxiliandi could save any plebeian from any patrician magistrate's decision. He could veto any act or proposal of any magistrate, including the tribunes of the people (ius intercedendi or ius intercessionis). His person was held to be sacrosanct.

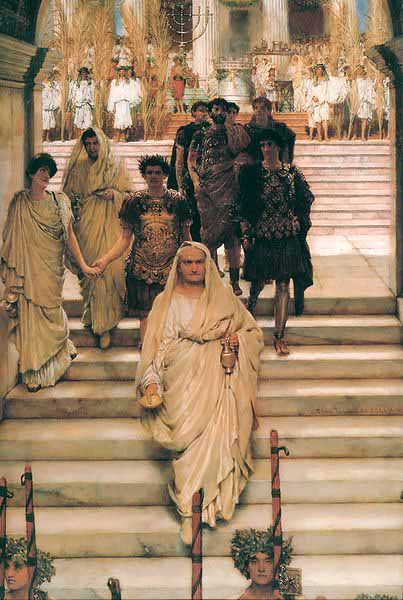

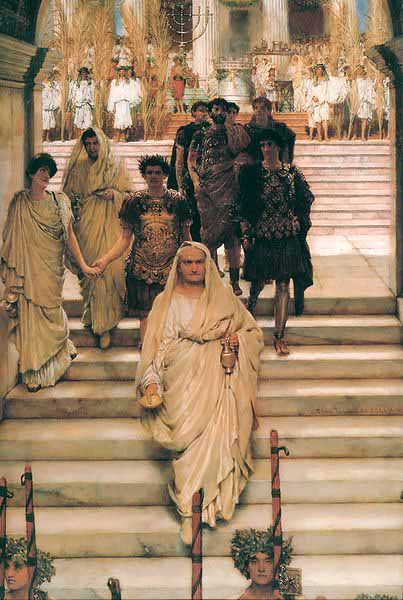

Roman magistrates on official business were expected to wear the form of toga associated with their office; different togas were worn by different ranks; senior magistrates had the right to togas bordered with purple. A triumphal imperator of the Republic had the right to wear the toga picta (of solid purple, richly embroidered) for the duration of the triumphal rite. During the Late Republic, the most powerful had this right extended. Pompey and Caesar are both thought to have worn the triumphal toga and other triumphal dress at public functions. Later emperors were distinguished by wearing togae purpurae, purple togas; hence the phrase "to don the purple" for the assumption of imperial dignity.

The titles customarily associated with the imperial dignity are imperator ("commander", lit. "one who prepares against"), which emphasizes the emperor's military supremacy and is the source of the English word emperor; caesar, which was originally a name but it came to be used for the designated heir (as Nobilissimus Caesar, "Most Noble Caesar") and was retained upon accession. The ruling emperor's title was the descriptive augustus ("majestic" or "venerable", which had tinges of the divine), which was adopted upon accession.

In Diocletian's Tetrarchy, the traditional seniorities were maintained: Augustus was reserved for the two senior emperors and Caesar for the two junior emperors - each delegated a share of power and responsibility but each an emperor-in-waiting, should anything befall his senior.

As princeps senatus (lit., "first man of the senate"), the emperor could receive foreign embassies to Rome; some emperors (such as Tiberius) are known to have delegated this task to the Senate. In modern terms these early emperors would tend to be identified as chiefs of state. The office of princeps senatus, however, was not a magistracy and did not own imperium. At some points in the Empire's history, the emperor's power was nominal; powerful praetorian prefects, masters of the soldiers and on a few occasions, other members of the Imperial family including Imperial mothers and grandmothers acted as the true source of power.

The title imperator dates back to the Roman Republic, when a victorious commander could be hailed as imperator in the field by his troops. The Senate could then award (or withhold) the extraordinary honor of a triumph; the triumphal commander retained the title until the end of his magistry. Roman tradition held the first triumph as that of Romulus but the first attested recipient of the title imperator in a triumphal context is Aemilius Paulus in 189 BC. It was a title held with great pride: Pompey was hailed imperator more than once, as was Sulla, but it was Julius Caesar who first used it permanently - according to Dio, this was a singular and excessive form of flattery granted by the Senate, passed to Caesar's adopted heir along with his name and virtually synonymous with it.

In 38 BC Agrippa refused a triumph for his victories under Octavian's command and this precedent established the rule that the princeps should assume both the salutation and title of imperator. It seems that from then on Octavian (later first emperor Augustus) used imperator as a praenomen (Imperator Caesar not Caesar imperator). From this the title came to denote the supreme power and was commonly used in that sense. Otho was the first to imitate Augustus but only with Vespasian did imperator (emperor) become the official title by which the ruler of the Roman Empire was known.

The word princeps (plural principes), meaning "first", was a republican term used to denote the leading citizen(s) of the state. It was a purely honorific title with no attached duties or powers. It was the title most preferred by Caesar Augustus as its use implies only primacy, as opposed to another of his titles, imperator, which implies dominance. Princeps, because of its republican connotation, was most commonly used to refer to the emperor in Latin (although the emperor's actual constitutional position was essentially "pontifex maximus with tribunician power and imperium superseding all others") as it was in keeping with the faćade of the restored Republic; the Greek word basileus ("king") was modified to be synonymous with emperor (and primarily came into favor after the reign of Heraclius) as the Greeks had no republican sensibility and openly viewed the emperor as a monarch.

In the era of Diocletian and beyond, princeps fell into disuse and was replaced with dominus ("lord"); later emperors used the formula Imperator Caesar NN. Pius Felix (Invictus) Augustus. NN representing the individual's personal name, Pius Felix, meaning "Pious and Blest", and Invictus meaning "undefeated". The use of princeps and dominus broadly symbolize the differences in the empire's government, giving rise to the era designations "Principate" and "Dominate".

At the end of the Roman Republic no new, and certainly no single title indicated the individual who held supreme power. Insofar as emperor could be seen as the English translation of imperator, then Julius Caesar had been an emperor, like several Roman generals before him. Instead, by the end of the civil wars in which Julius Caesar had led his armies, it became clear on the one hand that there was certainly no consensus to return to the old-style monarchy, and that on the other hand the situation where several officials, bestowed with equal power by the senate, fought one another had to come to an end.

Julius Caesar, then Octavian after him, accumulated offices and titles of the highest importance in the Republic, making the power attached to these offices permanent, and preventing anyone with similar aspirations from accumulating or maintaining power for themselves. However, Julius Caesar, unlike those after him, did so without the Senate's vote and approval.

Julius Caesar held the Republican offices of consul four times and dictator five times, was appointed dictator in perpetuity (dictator perpetuo) in 45 BC and had been "pontifex maximus" for several decades. He gained these positions by senatorial consent. By the time of his assassination in 44 BC he was the most powerful man in Rome.

In his will, Caesar appointed his adopted son Octavian as his heir. On Caesar's death, Octavian inherited his adoptive father's property and lineage, the loyalty of most of his allies and - again through a formal process of senatorial consent – an increasing number of the titles and offices that had accrued to Caesar. A decade after Caesar's death, Octavian's victory over his erstwhile ally Mark Antony at Actium put an end to any effective opposition and confirmed Octavian's supremacy.

In 27 BC, Octavian appeared before the Senate and offered to retire from active politics and government; the Senate not only requested he remain, but increased his powers and made them lifelong, awarding him the title of Augustus (the elevated or divine one, somewhat less than a god but approaching divinity). Octavian stayed in office till his death; the sheer breadth of his superior powers as princeps and permanent imperator of Rome's armies guaranteed the peaceful continuation of what nominally remained a republic. His "restoration" of powers to the Senate and the people of Rome was a demonstration of his auctoritas and pious respect for tradition.

Even at Augustus' death, some later historians such as Tacitus would say that the true restoration of the Republic might have been possible. Instead, Augustus actively prepared his adopted son Tiberius to be his replacement and pleaded his case to the Senate for inheritance through merit. The Senate disputed the issue but eventually confirmed Tiberius as princeps. Once in power, Tiberius took considerable pains to observe the forms and day-to-day substance of republican government.

The historians of the 1st centuries observed the dynastic continuity: if a hereditary monarchy-not-by-kings existed after the republic, it had started with Julius Caesar. In this sense Suetonius wrote of The Twelve Caesars, meaning the emperors from Julius Caesar to the Flavians included (where, after Nero, the inherited name had turned into a title), and emperors adopted themselves into an Imperial lineage.

By the end of the 3rd century AD, the Roman Empire was split into Western and an Eastern parts, each with its own augustis or caesares. Roman rule had disintegrated somewhat earlier in the century as a result of Germanic invasions which had overrun much of the Western Empire, and imperial authority now ran in the disconnected regions of Italy, Sicily, the Alps, Dalmatia, northwestern Gaul, and what is modern Morocco.[citation needed]

The succession of Western Emperors ended after a set of military coup d'etat in Italy during 475 and 476. In 475, Orestes, the Magister militum ("master of soldiers", equivalent to general of the army) in the west, revolted against Emperor Julius Nepos and seized the Italian Peninsula. Orestes then pronounced his own son, Romulus Augustus, as Emperor. Nepos fled to Dalmatia and continued to have the allegiance of the balance of the Western Empire (essentially northern Gaul, Dalamatia, and Morocco) and the backing of the Eastern Empire authorities. Orestes was never able to consolidate power beyond Italy, or gain the Eastern Emperor's recognition for his son's ascension, and when he failed to make good on his promises to the Foederati (foreign mercenaries), they rose up against him.

Less than a year after his proclamation, Romulus Augustus was deposed by the German Odoacer, leader of the Foederati. Although he had the strong support of the Senate and enjoyed good relations with the Pope, Odoacer refrained from taking the imperial title and ruled in Nepos' name during the remaining four years of the latter's life. Nevertheless he was de facto an autonomous king, and his ascension is generally used by historian to mark the end of Antiquity and the beginning of the Early Middle Ages, also known as the Dark Ages. Upon Nepos' death in 480, Odoacer pursued his assassins, expanding his rule to include Dalmatia as a consequence. Emperor Zeno, with the support of the Roman Senate officially abolished the separate Western Empire at this time and thereafter the unitary empire was ruled from the eastern capitol of Constantinople.

The Roman Empire survived in the east until 1453, but the marginalization of the former heartland of Italy to the empire would have profound cultural impacts on the empire and the position of emperor. In 620, the official language was changed from Latin to Greek, and although the Greek-speaking inhabitants were Romaioi and were still considered Romans by themselves and the populations of Eastern Europe, the Near East, India, and China, many in Western Europe began to refer to the political entity as the "Greek Empire".

The evolution of the church in the no-longer imperial city of Rome and the church in the now supreme Constantinople began to follow divergent paths culminating in the split between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox faiths. The position of emperor was increasingly influenced by Near Eastern concepts of kingship.

Starting with Emperor Heraclius, Roman emperors styled themselves "King of Kings" (form the imperial Persian "Shananshah") from 627 and "Basileus" (from the title used by Alexander the Great) from 629. The later period of the empire is today called the Byzantine Empire as a matter of scholarly convention.

The line of Roman emperors in the Eastern Roman Empire continued unbroken until the fall of Constantinople in 1453 under Constantine XI Palaiologos. These emperors eventually normalized the imperial dignity into the modern conception of an emperor, incorporated it into the constitutions of the state, and adopted the aforementioned title i>Basileus kai autokrator Rhomaion - Emperor of the Romans. These emperors ceased to use Latin as the language of state after Heraclius. Historians have customarily treated the state of these later Eastern emperors under the name "Byzantine Empire", though Byzantine is not a term that the Byzantines ever used to describe themselves.

Constantine XI Palaiologos was the last reigning Roman emperor. A member of the Palaiologos dynasty, he ruled the feeble remnant of the Eastern Roman Empire from 1449 until his death in 1453 defending its capital Constantinople.

He was born in Mystra as the eighth of ten children of Manuel II Palaiologos and Helena Dragas he daughter of the Serbian prince Constantine Dragas of Kumanovo. He spent most of his childhood in Constantinople under the supervision of his parents. During the absence of his older brother in Italy, Constantine was regent in Constantinople from 1437-1440.

Before the beginning of the siege, Mehmed II made an offer to Constantine XI. In exchange for the surrender of Constantinople, the emperor's life would be spared and he would continue to rule in Mystra. Constantine refused this offer. Instead he led the defense of the city and took an active part in the fighting along the land walls. At the same time, he used his diplomatic skills to maintain the necessary unity between the Genovese, Venetian, and Byzantine troops. As the city fell on May 29, 1453, Constantine is said to have remarked: "The city is fallen but I am alive." Realizing that the end had come, he reportedly discarded his purple cloak and led his remaining soldiers into a final charge, in which he was killed. With his death, Roman imperial succession came to an end, almost 1500 years after Augustus.

After the fall of Constantinople, Thomas Palaiologos, brother of Constantine XI, was elected emperor and tried to organize the remaining forces. His rule came to an end after the fall of the last major Byzantine city, Corinth. He then moved in Italy and continued to be recognized as Eastern emperor by the Christian powers.

His son Andreas Palaiologos continued claims on the Byzantine throne until he sold the title to Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, the grandparents of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

The concept of the Roman Empire was renewed in the West with the coronation of the king of the Franks, Charlemagne, as Roman emperor by the Pope on Christmas Day, 800. This line of Roman emperors was actually generally Germanic rather than Roman, but maintained their Roman-ness as a matter of principle. These emperors used a variety of titles (most frequently "Imperator Augustus") before finally settling on Imperator Romanus Electus ("Elected Roman Emperor").

Historians customarily assign them the title "Holy Roman Emperor", which has a basis in actual historical usage, and treat their "Holy Roman Empire" as a separate institution. To Latin Christians of the time, the Pope was the temporal authority as well as spiritual authority, and as Bishop of Rome he was recognized as having the power to anoint or crown a new Roman emperor.

The title of "Western Roman emperor" was further legitimized when the Eastern Roman emperor at Constantinople recognized Charlemagne as Basileus of the West. The last man to hold the title of proper Roman emperor and to be crowned by the pope (although in Bologna, not Rome) was Charles V. All his successors bore only a title of "emperor-elect". Charles V was also the last man to celebrate a triumph in Rome.

The line of "emperor-elect" rulers lasted until 1806 when Francis II dissolved the Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. Despite the existence of later potentates styling themselves "emperor", such as the Napoleons, the Habsburg Emperors of Austria, and the Hohenzollern heads of the German Reich, this marked the end of the Western Empire. Although there is a living heir to the Habsburg dynasty, as well as a Pope and pretenders to the positions of the electors, and although all the medieval coronation regalia are still preserved in Austria, the legal abolition of all aristocratic prerogatives of the former electors and the imposition of republican constitutions in Germany and Austria removed the potential for a revival of the Holy Roman Empire.

Although these are the most common offices, titles, and positions, one should note that not all Roman emperors used them, nor were all of them used at the same time in history. The consular and censorial offices especially were not an integral part of the Imperial dignity, and were usually held by persons other than the reigning emperor.

When Augustus established the Princeps, he turned down supreme authority in exchange for a collection of various powers and offices, which in itself was a demonstration of his auctoritas ("authority"). As holding princeps senatus, the emperor declared the opening and closure of each Senate session, declared the Senate's agenda, imposed rules and regulation for the Senate to follow, and met with foreign ambassadors in the name of the Senate. Being pontifex maximus made the emperor the chief administrator of religious affairs, granting him the power to conduct all religious ceremonies, consecrate temples, control the Roman calendar (adding or removing days as needed), appoint the vestal virgins and some flamens, lead the Collegium Pontificum, and summarize the dogma of the Roman religion.

While these powers granted the emperor a great deal of personal pride and influence, they did not include legal authority. In 23 BC, Augustus gave the emperorship its legal power. The first was Tribunicia Potestas, or the powers of the tribune of the plebs without actually holding the office (which would have been impossible, since a tribune was by definition a plebeian, whereas the emperor was by definition a patrician). This endowed the emperor with inviolability (sacrosanctity) of his person, and the ability to pardon any civilian for any act, criminal or otherwise.

By holding the powers of the tribune, the emperor could prosecute anyone who interfered with the performance of his duties. The emperor's tribuneship granted him the right to convene the Senate at his will and lay proposals before it, as well as the ability to veto any act or proposal by any magistrate, including the actual tribune of the plebeians. Also, as holder of the tribune's power, the emperor would convoke the Council of the People, lay legislation before it, and served as the council's president. But his tribuneship only granted him power within Rome itself. He would need another power to veto the act of governors and that of the consuls while in the provinces.

To solve this problem, Augustus managed to have the emperor be given the right to hold two types of imperium. The first being consular imperium while he was in Rome, and imperium maius outside of Rome. While inside the walls of Rome, the reigning consuls and the emperor held equal authority, each being able to veto each other's proposals and acts, with the emperor holding all of the consul's powers. But outside of Rome, the emperor outranked the consuls and could veto them without the same effects on himself. Imperium Maius also granted the emperor authority over all the provincial governors, making him the ultimate authority in provincial matters and gave him the supreme command of all of Rome's legions. With Imperium Maius, the emperor was also granted the power to appoint governors of imperial provinces without the interference of the Senate. Also, Imperium Maius granted the emperor the right to veto the governors of the provinces and even the reigning consul while in the provinces.

The nature of the imperial office and the Principate was established under Julius Caesar's heir and posthumously adopted son, Caesar Augustus, and his own heirs, the descendants of his wife Livia from her first marriage to a scion of the distinguished Claudian clan. This Julio-Claudian dynasty came to an end when the Emperor Nero - a great-great-grandson of Augustus through his daughter and of Livia through her son - was deposed in 68.

Nero was followed by a succession of usurpers throughout 69, commonly called the "Year of the Four Emperors". The last of these, Vespasian, established his own Flavian dynasty.

Nerva, who replaced the last Flavian emperor, Vespasian's son Domitian, in 96, was elderly and childless, and chose therefore to adopt an heir, Trajan, from outside his family. When Trajan acceded to the purple he chose to follow his predecessor's example, adopting Hadrian as his heir, and the practice then became the customary manner of imperial succession for the next century, producing the "Five Good Emperors" and the Empire's period of greatest stability.

The last of the Good Emperors, Marcus Aurelius, chose his natural son Commodus as his successor rather than adopting an heir. Commodus' misrule led to his murder on 31 December 192, following which a brief period of instability quickly gave way to Septimius Severus, who established the Severan dynasty which, except for an interruption in 217-218, held the purple until 235.

The accession of Maximinus Thrax marks both the close and the opening of an era. It was one of the last attempts by the increasingly impotent Roman Senate to influence the succession. Yet it was the second time that a man had achieved the purple while owing his advancement purely to his military career; both Vespasian and Septimius Severus had come from noble or middle class families, while Thrax was born a commoner. He never visited the city of Rome during his reign, which marks the beginning of a series of "barracks emperors" who came from the army. Between 235 and 285 over a dozen emperors achieved the purple, but only Valerian and Carus managed to secure their own sons' succession to the throne; both dynasties died out within two generations.

The accession to the purple on 20 November 284, of Diocletian, the lower-class, Greek-speaking Dalmatian commander of Carus's and Numerian's household cavalry (protectores domestici), marked a major departure from traditional Roman constitutional theory regarding the emperor, who was nominally first among equals; Diocletian introduced oriental despotism into the imperial dignity.

Whereas before emperors had worn only a purple toga (toga purpura) and been greeted with deference, Diocletian wore jeweled robes and shoes, and required those who greeted him to kneel (proskynesis) and kiss the hem of his robe (adoratio). In many ways, Diocletian was the first monarchical emperor, and this is symbolized by the fact that the word dominus ("Lord") rapidly replaced princeps as the favored word for referring to the emperor. Significantly, neither Diocletian nor his co-emperor, Maximian, spent much time in Rome after 286, establishing their imperial capitals at Nicomedia and Mediolanum (modern Milan), respectively.

Diocletian established the Tetrarchy, a system by which the Roman Empire was divided into East and West, with each having an Augustus to rule over it and a Caesar to assist him. The Tetrarchy ultimately degenerated into civil war, but the eventual victor, Constantine the Great, restored Diocletian's system of dividing the Empire into East and West. He kept the East for himself and founded his city of Constantinople as its new capital.

The dynasty Constantine established was also soon swallowed up in civil war and court intrigue until it was replaced, briefly, by Julian the Apostate's general Jovian and then, more permanently, by Valentinian I and the dynasty he founded in 364. Though he was a soldier from a low middle class background, Valentinian was not a barracks emperor; he was elevated to the purple by a conclave of senior generals and civil officials.

Theodosius I acceded to the purple in the East in 379 and in the West in 394. He outlawed paganism and made Christianity the Empire's official religion. He was the last emperor to rule over a united Roman Empire; the distribution of the East to his son Arcadius and the West to his son Honorius after his death in 395 represented a permanent division.

In the West, the office of emperor soon degenerated into being little more than a puppet of a succession of Germanic tribal kings, until finally the Heruli Odoacer simply overthrew the child-emperor Romulus Augustulus in 476, shipped the imperial regalia to the Emperor Zeno in Constantinople and became King of Italy.

Though during his own lifetime Odoacer maintained the legal fiction that he was actually ruling Italy as the viceroy of Zeno, historians mark 476 as the traditional date of the fall of the Roman Empire in the West. Large parts of Italy (Sicily, the south part of the peninsula, Ravenna, Venice etc.), however, remained under actual imperial rule from Constantinople for centuries, with imperial control slipping or becoming nominal only as late as the 11th century.

In the East, the Empire continued until the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. Although known as the Byzantine Empire by contemporary historians, the Empire was simply known as the Roman Empire to its citizens and neighboring countries.