The Late Period of Ancient Egypt refers to the last flowering of native Egyptian rulers after the Third Intermediate Period from the 26th Saite Dynasty into Persian conquests and ended with the conquest by Alexander the Great. It ran from 664 BC until 323 BC. It is often regarded as the last gasp of a once great culture, where the power of Egypt had diminished.

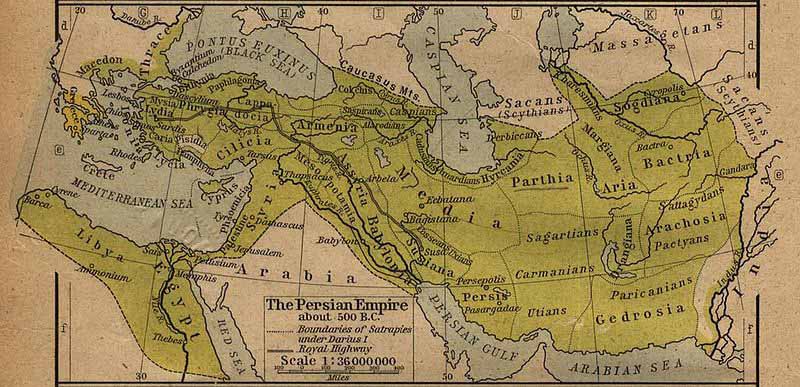

It all ends with the thirty-first Dynasty of Egypt also known as the Second Egyptian Satrapy. It was effectively a short-living province of the Achaemenid Persian Empire between 343 BCE to 332 BCE. In 332 BC Mazaces handed over the country to Alexander the Great without a fight. The Achaemenid empire had ended, and for a while Egypt was a satrapy in Alexander's empire. Later the Ptolemies and the Romans successively ruled the Nile valley.

The history of Achaemenid Egypt is divided into two eras: an initial period of Achaemenid Persian occupation when Egypt became a satrapy, followed by an interval of independence; and a second period of occupation, again under the Achaemenids.

The last pharaoh of the Twenty-Sixth dynasty, Psamtik III, was defeated by Cambyses II of Persia in the battle of Pelusium in the eastern Nile delta in 525 BC. Egypt was then joined with Cyprus and Phoenicia in the sixth satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire. Thus began the first period of Persian rule over Egypt (also known as the 27th Dynasty), which ended around 402 BC.

After an interval of independence, during which three indigenous dynasties reigned (the 28th, 29th, and 30th dynasty), Artaxerxes III (358-338 BC) reconquered the Nile valley for a brief second period (343-332 BC), which is called the thirty-first dynasty of Egypt.

Cambyses led three unsuccessful military campaigns in Africa: against Carthage, the Siwa Oasis, and Nubia. He remained in Egypt until 522 BC and died on the way back to Persia. The Greek and Jewish sources, especially Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus, present us a bleak portrait of Cambyses' rule, describing the king as mad, ungodly, and cruel. It is impossible unfortunately to compare these texts with Egyptian sources, as all unofficial documents appear doing their best to ignore Cambyses' existence.

Herodotus may have drawn on an indigenous tradition that reflected the Egyptians' resentment, especially of the clergy, of Cambyses' decree (known from a Demotic text on the back of papyrus no. 215 in the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris) curtailing royal grants made to Egyptian temples under Ahmose II.

In order to regain the support of the powerful priestly class, Darius I (522-486 BC) revoked Cambyses' decree. Diodorus reported that Darius was the sixth and last lawmaker for Egypt; according to Demotic papyrus no. 215, in the third year of his reign he ordered his satrap in Egypt, Aryandes, to bring together wise men among the soldiers, priests, and scribes, in order to codify the legal system that had been in use until the year 44 of Ahmose II (c. 526 BC).

The laws were to be transcribed on papyrus in both Demotic and Aramaic, so that the satraps and their officials, mainly Persians and Babylonians, would have a legal guide in both the official language of the empire and the language of local administration. To facilitate commerce, Darius built a navigable waterway from the Nile to the Red Sea (from Bubastis [modern Zaqaziq] through the Wadi Tumelat and the Bitter Lakes); it was marked along the way by four great bilingual stelae, the so-called "canal stelae," inscribed in both hieroglyphics and cuneiform scripts.

In 1972 archaeological excavations at Susa brought to light a stone statue of Darius I, standing and wearing a sumptuous Persian garment; it is inscribed in cuneiform (in Old Persian, Elamite, and Akkadian) and in hieroglyphics. This can be interpreted as a recognition of the role of Egypt in the Empire.

Shortly before 486 BC, the year of Darius' death, there was a revolt of the type that had occurred under Aryandes, that was definitively subdued by Xerxes I (486Ð464 BC) only in 484 BC. The province was subjected to harsh punishment for the revolt, and especially its satrap Achaemenes administered the country without regard for the opinion of his subjects.

A still more serious and extensive revolt took place in about 460 BC under Artaxerxes I. It was led by the Libyan Inaros, son of Psamtik III (Thucydides 1.104), who asked for help from Athens; a fleet of 200 ships sailed up the Nile as far as the ancient citadel of Memphis, two thirds of which was occupied by the insurgents. Achaemenes was killed in the course of the battle of Papremis in the western Delta.

t is not known who served as satrap after Artaxerxes III, but under Darius III (336Ð330 BC) there was Sabaces, who fought and died at Issus and was succeeded by Mazaces. Egyptians also fought at Issus, for example, the nobleman Somtutefnekhet of Heracleopolis, who described on the "Naples stele" how he escaped during the battle against the Greeks and how Arsaphes, the god of his city, protected him and allowed him to return home.

In 332 BC Mazaces handed over the country to Alexander the Great without a fight. The Achaemenid empire had ended, and for a while Egypt was a satrapy in Alexander's empire. Later the Ptolemies and the Romans successively ruled the Nile valley.

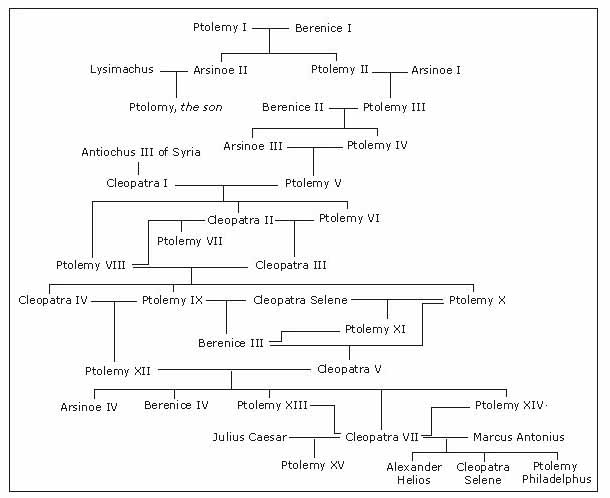

The Ptolemaic dynasty was a Macedonian Greek royal family which ruled the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt during the Hellenistic period. Their rule lasted for 275 years, from 305 BC to 30 BC. They were the 32nd and last dynasty of ancient Egypt. The Ptolemaic dynasty is sometimes called the Thirty-fourth dynasty of Egypt too.

Ptolemy, one of the six somatophylakes (bodyguards) who served as Alexander the Great's generals and deputies, was appointed satrap of Egypt after Alexander's death in 323 BC. In 305 BC, he declared himself King Ptolemy I, later known as "Soter" (saviour). The Egyptians soon accepted the Ptolemies as the successors to the pharaohs of independent Egypt. Ptolemy's family ruled Egypt until the Roman conquest of 30 BC.

All the male rulers of the dynasty took the name Ptolemy. Ptolemaic queens, some of whom were the sisters of their husbands, were usually called Cleopatra, Arsinoe or Berenice. The most famous member of the line was the last queen, Cleopatra VII, known for her role in the Roman political battles between Julius Caesar and Pompey, and later between Octavian and Mark Antony. Her apparent suicide at the conquest by Rome marked the end of Ptolemaic rule in Egypt.

The Ptolemaic Kingdom in and around Egypt began following Alexander the Great's conquest in 332 BC and ended with the death of Cleopatra VII and the Roman conquest in 30 BC. It was founded when Ptolemy I Soter declared himself Pharaoh of Egypt, creating a powerful Hellenistic state stretching from southern Syria to Cyrene and south to Nubia. Alexandria became the capital city and a center of Greek culture and trade. To gain recognition by the native Egyptian populace, they named themselves the successors to the Pharaohs. The later Ptolemies took on Egyptian traditions by marrying their siblings, had themselves portrayed on public monuments in Egyptian style and dress, and participated in Egyptian religious life. Hellenistic culture thrived in Egypt until the Muslim conquest. The Ptolemies had to fight native rebellions and were involved in foreign and civil wars that led to the decline of the kingdom and its annexation by the Roman Empire.

The Greco-Roman world, Greco-Roman culture, or the term Greco-Roman when used as an adjective, as understood by modern scholars and writers, refers to those geographical regions and countries that culturally (and so historically) were directly, protractedly and intimately influenced by the language, culture, government and religion of the ancient Greeks and Romans. In exact terms the area refers to the "Mediterranean world", the extensive tracts of land centered on the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins, the "swimming-pool and spa" of the Greeks and Romans, i.e. one wherein the cultural perceptions, ideas and sensitivities of these peoples were dominant.

The term Greco-Roman world describes those regions who were for many generations subjected to the government of the Greeks and then the Romans and thus accepted or at length were forced to embrace them as their masters and teachers. This process was aided by the seemingly universal adoption of Greek as the language of intellectual culture and at least Eastern commerce, and of Latin as the tongue for public management and forensic advocacy, especially in the West (from the perspective of the Mediterranean Sea).

Though these languages never became the native idioms of the rural peasants (the great majority of the population), they were the languages of the urbanites and cosmopolitan elites, and at the very least intelligible (see lingua franca), if only as corrupt or multifarious dialects to those who lived within the large territories and populations outside of the Macedonian settlements and the Roman colonies. Certainly, all men of note and accomplishment, whatever their ethnic extractions, spoke and wrote in Greek and/or Latin.

Thus, the Roman jurist and Imperial chancellor Ulpian was Phoenician, the Greco-Egyptian mathematician and geographer Claudius Ptolemy was a Roman citizen and the famous post-Constantinian thinkers John Chrysostom and Augustine were pure Syrian and Berber respectively. The historian Josephus Flavius was Jewish but he also wrote and spoke in Greek and was a Roman citizen.

Properly speaking, the term "Greco-Roman World" signifies the entire realm from the Atlas Mountains to the Caucasus, from northernmost Britain to the Hejaz, from the Atlantic coast of Iberia to the Upper Tigris River and from the point at which the Rhine enters the North Sea to the northern Sudan. The Black Sea basin, particularly the renowned country of Dacia or Romania, the Tauric Chersonesus or the Crimea, and the Caucasic kingdoms which straddle both the Black and Caspian Seas are deemed to comprehend this definition as well. As the Greek Kingdoms of Western Asia successively fell before the reputedly invincible arms of Rome, and then were gradually incorporated into the universal empire of the Caesars, the diffusion of Greek political and social culture and that of Roman "law and liberty" converted these areas into parts of the Greco-Roman World.

Based on the above definition, it can be confidently asserted that the "cores" of the Greco-Roman world were Greece, Cyprus, Italy, the Iberian Peninsula, Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt and Africa Proper (Tunisia and Libya). Occupying the periphery of this world were "Roman Germany" (the Alpine countries and the so-called Agri Decumates, the territory between the Main, the Rhine and the Danube), Illyria and Pannonia (the former Yugoslavia and Hungary), Moesia (roughly corresponds to modern Bulgaria), Dacia (roughly corresponds to modern Romania), Nubia (roughly corresponds to modern northern Sudan), Mauretania (modern Morocco and western Algeria), Arabia Petraea (the Hejaz and Jordan, with modern Egypt's Sinai Peninsula), Mesopotamia (northern Iraq and Syria beyond the Euphrates), the Tauric Chersonesus (modern Crimea in Ukraine), Kingdom of Armenia and the suppliant kingdoms which swathed the Caucasus Mountains, namely Colchis, and the Caucasian Albania and Caucasian Iberia.

Based on the above definition, it can be confidently asserted that the "cores" of the Greco-Roman world were Greece, Cyprus, Italy, the Iberian Peninsula, Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt and Africa Proper (Tunisia and Libya). Occupying the periphery of this world were "Roman Germany" (the Alpine countries and the so-called Agri Decumates, the territory between the Main, the Rhine and the Danube), Illyria and Pannonia (the former Yugoslavia and Hungary), Moesia (roughly corresponds to modern Bulgaria), Dacia (roughly corresponds to modern Romania), Nubia (roughly corresponds to modern northern Sudan), Mauretania (modern Morocco and western Algeria), Arabia Petraea (the Hejaz and Jordan, with modern Egypt's Sinai Peninsula), Mesopotamia (northern Iraq and Syria beyond the Euphrates), the Tauric Chersonesus (modern Crimea in Ukraine), Kingdom of Armenia and the suppliant kingdoms which swathed the Caucasus Mountains, namely Colchis, and the Caucasian Albania and Caucasian Iberia.

In the schools of art, philosophy and rhetoric, the foundations of education were transmitted throughout the lands of Greek and Roman rule. Within its educated class, spanning all of the "Greco-Roman" era, the testimony of literary borrowings and influences is overwhelming proof of a mantle of mutual knowledge. For example, several hundred papyrus volumes found in a Roman villa at Herculaneum are in Greek.

From the lives of Cicero and Julius Caesar, it is known that Romans frequented the schools in Greece. The installation both in Greek and Latin of Augustus' monumental eulogy, the Res Gestae, is a proof of official recognition for the dual vehicles of the common culture. The familiarity of figures from Roman legend and history in the "Parallel Lives" composed by Plutarch is one example of the extent to which "universal history" was then synonymous with the accomplishments of famous Latins and Hellenes. Most educated Romans were likely bilingual in Greek and Latin.

Greco-Roman architecture is abundant in columns and size. There are two primary types of Greco-Roman architecture, Doric and Ionic. Examples of Doric architecture are the Parthenon and the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, while the Erechtheum, which is located right next to the Parthenon is Ionic. Ionic Greco-Roman architecture tend to be more decorative than the formal Doric styles. The most surviving buildings of Roman-Greco Architecture lean towards the temples, due to the building material used, although limestone does decay over time with natural erosion.

he Romans made it possible for individuals from subject-peoples to acquire Roman citizenship, and would sometimes confer citizenship on whole communities; thus, "Roman" became less and less an ethnic and more and more a political designation. By 211 AD, with Caracalla's edict known as the Constitutio Antoni'niana, all free inhabitants of the Empire became citizens. As a result, even after the city of Rome fell, the people of what remained of the empire (referred to by many historians as the Byzantine Empire) continued to call themselves Romans, even though Greek became the main language of the Empire. Rhomaioi continued as their name for themselves (Hellenes referring to pagan Greeks) through the Ottoman and even into modern times.