Trilobites are a well-known fossil group of extinct marine arthropods that form the class Trilobita. The first appearance of trilobites in the fossil record defines the base of the Atdabanian stage of the Early Cambrian period (526 million years ago), and they flourished throughout the lower Paleozoic era before beginning a drawn-out decline to extinction when, during the Devonian, almost all trilobite orders, with the sole exception of Proetida, died out. Trilobites finally disappeared in the mass extinction at the end of the Permian about 250 million years ago. The trilobites were among the most successful of all early animals, roaming the oceans for over 270 million years.

When trilobites first appeared in the fossil record they were already highly diverse and geographically dispersed. Because trilobites had wide diversity and an easily fossilized exoskeleton an extensive fossil record was left behind, with some 17,000 known species spanning Paleozoic time. The study of these fossils has facilitated important contributions to biostratigraphy, paleontology, evolutionary biology and plate tectonics. Trilobites are often placed within the arthropod subphylum Schizoramia within the superclass Arachnomorpha (equivalent to the Arachnata), although several alternative taxonomies are found in the literature.

Trilobites had many life styles; some moved over the sea-bed as predators, scavengers or filter feeders and some swam, feeding on plankton. Most life styles expected of modern marine arthropods are seen in trilobites, with the possible exception of parasitism (where there are still scientific debates). Some trilobites (particularly the family Olenidae) are even thought to have evolved a symbiotic relationship with sulfur-eating bacteria from which they derived food. Read more

Ancient trilobite limbs reveal unique walking and burrowing abilities in prehistoric seas PhysOrg - August 4, 2025

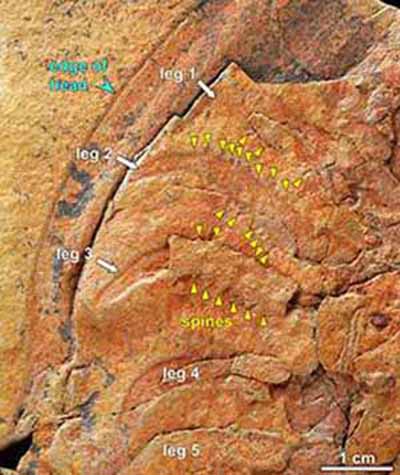

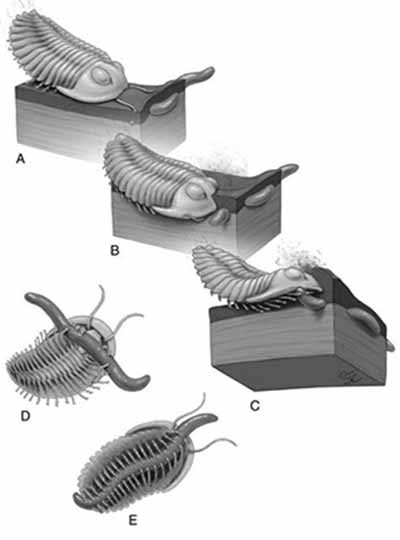

In a new study at Harvard, researchers analyzed 156 limbs from 28 O. serratus fossil specimens to reconstruct the precise movement and function of these ancient arthropod appendages - shedding light on one of the planet's earliest and most successful animals.

Meet The Trilobite Beetles: Prehistoric-Looking Insects With Peculiar Sex Lives Live Science - August 6, 2024

Stumble upon a certain kind of beetle in South-East Asia’s tropical forests, and you’d be forgiven for wondering why there was a prehistoric ocean creature lurking in the leaves. But fear not, someone hasn’t been Jurassic Park-ing – it’s a trilobite beetle, and its bizarreness goes beyond looking like its namesake.

508-Million-Year-Old Pompeii Trilobite Fossils Show Never-Before-Seen Features IFL Science - June 28, 2024

The trilobites were entombed in pyroclastic flow, which is the hot, dense material that comes hurtling out of volcanoes sometimes reaching speeds as high as 200 meters (656 feet) per second. Typically, it burns up any life in its path, but that can change in a marine setting.

Rare Fossil Reveals What One Trilobite Had For Dinner 465 Million Years Ago IFL Science - September 27, 2023

The uniquely well-preserved fossil is a Bohemolichas incola specimen, and it represents the most detailed dietary reference we have for these animals. Dating back to the Ordovician, it was retrieved inside a siliceous nodule, also known as a “Rokycany ball”. These curious balls act sort of like a prehistoric Kinder Surprise that can be cleaved in two to reveal preserved animals.

Ancient Trilobites Had Crystal Eyes, And They're Still a Mystery Science Alert - July 12, 2023

Rare Fossil Reveals What One Trilobite Had For Dinner 465 Million Years Ago

Arthropods formed orderly lines 480 million years ago Science Daily - October 17, 2019

Researchers studied fossilized Moroccan Ampyx trilobites, which lived 480 million years ago and showed that the trilobites had probably been buried in their positions -- all oriented in the same direction. Scientists deduced that these Ampyx processions may illustrate a kind of collective behavior adopted in response to cyclic environmental disturbances. Though our understanding of the anatomy of the earliest animals is growing ever more precise, we know next to nothing about their behavior.

Reconstruction of trilobite ancestral range in the southern hemisphere PhysOrg - January 10, 2019

The first appearance of trilobites in the fossil record dates to 521 million years ago in the oceans of the Cambrian Period, when the continents were still inhospitable to most life forms. Few groups of animals adapted as successfully as trilobites, which were arthropods that lived on the seabed for 270 million years until the mass extinction at the end of the Permian approximately 252 million years ago.

Trilobite Tummies Revealed in New Fossils Live Science - September 25, 2017

Trilobite tummies were more complex than previously believed, new fossils reveal. The fossils, which hail from China, preserve the guts of trilobites in long, iron-rich strips. Trilobite fossils are a dime a dozen - sort of like cockroaches of the sea in that respect. They were abundant for nearly 300 million years before they went extinct about 252 million years ago - but trilobite fossils that reveal internal organs are rare

Fossils reveal unseen 'footprint' maker PhysOrg - January 17, 2017

Fossils found in Morocco from the long-extinct group of sea creatures called trilobites, including rarely seen soft-body parts, may be previously unseen animals that left distinctive fossil 'footprints' around the ancient supercontinent Gondwana. The trilobites were a very common group of marine animals during the 300 million years of the Palaeozoic Era with hard, calcified, external armor-like skeletons over their bodies. They disappeared with a mass extinction event about 250 million years ago which wiped out about 96% of all marine species.

Trilobites Were Stone-Cold Killers Live Science - February 11, 2016

Trilobites were savvy killers who hunted down their prey and used their many legs to wrestle them into submission, newly discovered fossils suggest. The fossils come from a site in southeastern Missouri, not far from the city of Desloge. They are trace fossils, which means they preserve not the organisms themselves, but their burrows. The burrows were made by various species of trilobite as well as by unknown, wormlike creatures. A statistical analysis of these burrows and their intersections shows that they cross one another more than expected, a sign that the trilobites were deliberately hunting down their wormy prey. In a subset of those cases, the trilobites seemed to sidle up to the burrows in parallel, perhaps so they could latch onto the worms lengthwise with their row of legs.

New evidence suggests earliest trilobites were able to partially roll up their bodies PhysOrg - September 25, 2013

A trio of researchers - two from Cambridge University and one from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, has found evidence that suggests that the earliest trilobites were able to roll up their bodies for protection, much as their later ancestors did. In their paper published in the journal Biology Letters, the team describes their examination of a fossil found in Alberta Canada, and how they ruled out other causes for its rolled up position.

Ancient Trilobites Featured Spotted Camouflage Live Science - March 26, 2013

Leopard-like patterns of spots on the shells of extinct horseshoe-crab-like trilobites may be the strongest evidence yet that the ancient armored creatures protected themselves with camouflage, according to researchers. Trilobites are distant, extinct relatives of lobsters, spiders and insects, resembling horseshoe crabs in appearance. These armored creatures prowled the seas for roughly 270 million years, longer than the age of dinosaurs lasted, and died off more than 250 million years ago, before dinosaurs rose to dominance. New species of trilobites are unearthed every year, making them the single most diverse class of extinct life known.

Even Ancient Trilobites Were Social Live Science - September 21, 2009

Seeking safety in numbers is an age-old maneuver - at least 465 million years old, it turns out. Ordovician-period fossils discovered in Portugal show groups of trilobites hiding out or molting together - rare clues to the ancient marine arthropods' social and survival behaviors. The fossils come from a roofing-slate quarry near the town of Oporto. Small trilobites often appear together in single files that zigzag or wave their way across the rock. It's as if predator-wary trilobites sought shelter in long, narrow tunnels, say Juan C. Gutierrez-Marco of the Institute of Economic Geology in Madrid and his colleagues, who analyzed the fossils. Other clusters are made up of hundreds of exuviae, the exoskeletons discarded by molting trilobites. The exuviae point every which way, a clue that a trilobite assembly, and not a water current, deposited them. Mass molting - followed by mass mating - is something trilobites' relatives the horseshoe crabs still do today. The new find joins other fossil groupings that indicate trilobites probably followed the same molt-mate pattern - mass actions being a good way for any one tender-shelled animal to protect itself and its spawn from being eaten.

Petrified Animals Trilobites Died Quickly Live Science - February 26, 2008

Scientists have discovered that ancient animals preserved in the famous Burgess Shale fossil deposit were killed by a mud slurry that buried them so deep their whole bodies were petrified. The finding solves a mystery that puzzled paleontologists since the revealing fossil trove was discovered in 1909 - how were the animals' bodies so well preserved?

Trilobite was ancient snack food BBC - April 14, 2004

Direct evidence has now been found to show that trilobites - among the most diverse of fossil animal groups - were eaten by other ancient sea creatures. Scientists discovered cracked trilobite body parts in the gut of a 510-million-year-old fossil marine animal.

Giant trilobite discovered BBC - October 9, 2000

The largest trilobite yet discovered has been identified by Canadian paleontologists. The creature, which dates from 445 million years ago, measures 72 centimetres in length. This is about twice the size of the previous record holder. Trilobites are an extinct group of sea-dwelling arthropods (animals with an outer skeleton and jointed body and limbs) that are distantly related to crabs, scorpions and beetles. They are probably the most common fossils of the Paleozoic Era (about 545-250 million years ago) and scientists use them to help date different layers of rock.

ANCIENT AND LOST CIVILIZATIONS