Romulus and Remus are the twin brothers and central characters of Rome's foundation myth. Their mother was Rhea Silvia, daughter to Numitor, king of Alba Longa. Before their conception, Numitor's brother Amulius had seized power, killed Numitor's male heirs and forced Rhea Silvia to become a Vestal Virgin, sworn to chastity. Rhea Silvia conceived the twins by the god Mars, or by the demi-god Hercules; once the twins were born, Amulius had them abandoned to die in the river Tiber.

The female wolf, feeding the baby twins Romulus and Remus

Image by Rubens

They were saved by a series of miraculous interventions: the river carried them to safety, a she-wolf found and suckled them, and a woodpecker fed them. A shepherd and his wife found and fostered them to manhood, as simple shepherds. The twins, still ignorant of their true origins, were natural leaders. Each acquired many followers. When they discovered the truth of their birth, they killed Amulius and restored Numitor to his throne. Rather than wait to inherit Alba Longa they chose to found a new city.

Romulus wanted to found a city on the Palatine Hill; Remus preferred the Aventine Hill. They agreed to determine the site through augury but when each claimed the results in his own favor, they quarreled and Remus was killed. Romulus founded the new city, named it Rome, after himself, and created its first legions and senate. The new city grew rapidly, swelled by landless refugees; as most were unmarried, Romulus arranged the abduction of women from the neighboring Sabines. The ensuing war ended with the joining of Sabines and Romans as one Roman people. Thanks to divine favor and Romulus' inspired leadership, Rome became a dominant force, but Romulus himself became increasingly autocratic, and disappeared or died in mysterious circumstances. In later forms of the myth, he ascended to heaven, and was identified with Quirinus, the divine personification of the Roman people.

The legend as a whole encapsulates Rome's ideas of itself, its origins and moral values. For modern scholarship, it remains one of the most complex and problematic of all foundation myths, particularly in the matter and manner of Remus' death. Ancient historians had no doubt that Romulus gave his name to the city. Most modern historians believe his name a back-formation from the name Rome; the basis for Remus' name and role remain subjects of ancient and modern speculation.

The myth was fully developed into something like an "official", chronological version in the Late Republican and early Imperial era; Roman historians dated the city's foundation to between 758 and 728 BC, and Plutarch reckoned the twins' birth year as c. 771 BC. An earlier tradition that gave Romulus a distant ancestor in the semi-divine Trojan prince Aeneas was further embellished; and Romulus was made the direct ancestor of Rome's first Imperial dynasty. Possible historical bases for the broad mythological narrative remain unclear and disputed. The image of the she-wolf suckling the divinely fathered twins became an iconic representation of the city and its founding legend, making Romulus and Remus preeminent among the feral children of ancient mythography.

In all versions of the founding myth, the twins grew up as shepherds. They came into conflict with the shepherds of Amulius, leading to battles in which Remus was captured and taken to Amulius, under the accusation of being a thief. Their identity was discovered. Romulus raised a band of shepherds to liberate his brother; Amulius was killed and Romulus and Remus were conjointly offered the crown. They refused it while their grandfather lived, and refused to live in the city as his subjects. They restored Numitor as king, paid due honors to their mother Rhea and left to found their own city, accompanied by a motley band of fugitives, runaway slaves, and any who wanted a second chance in a new city with new rulers.

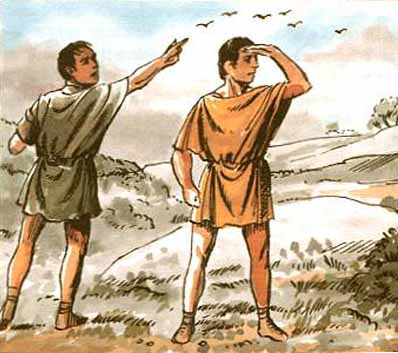

The brothers argued over the best site for the new city. Romulus favoured the Palatine Hill; Remus wanted the Aventine Hill. They agreed to select the site by divine augury, took up position on their respective hills and prepared a sacred space; signs were sent to each in the form of vultures, or eagles. Remus saw six; Romulus saw twelve, and claimed superior augury (foresight) as the basis of his right to decide.

Remus made a counterclaim: he saw his six vultures first. Romulus set to work with his supporters, digging a trench (or building a wall, according to Dionysius) around the Palatine to define his city boundary. Remus criticized some parts of the work and obstructed others. At last, Remus leaped across the boundary, as an insult to the city's defenses and their creator. For this, he was killed. The Roman ab urbe condita begins from the founding of the city, and places that date as 21 April 753 BC.

Livy gives two versions of Remus' death. In the one "more generally received", Remus criticizes and belittles the new wall, and in a final insult to the new city and its founder alike, he leaps over it. Romulus kills him, saying "So perish every one that shall hereafter leap over my wall". In the other version, Remus is simply stated as dead; no murder is alleged.

Two other, lesser known accounts have Remus killed by a blow to the head with a spade, wielded either by Romulus' commander Fabius (according to St. Jerome's version) or by a man named Celer. Romulus buries Remus with honor and regret.

Romulus and Remus decided to build a city where others who were homeless, as they once were, could come to live. The brothers argued over where to build the city. One night Romulus and Remus agreed to watch for an omen, a sign from the gods, to settle their argument.

The brothers fought over the meaning of the vultures

in the sky, and in a rage, Romulus killed Remus.

Romulus completes his city and names it Roma after himself. Then he divides his fighting men into regiments of 3000 infantry and 300 cavalry, which he calls "legions". From the rest of the populace he selects 100 of the most noble and wealthy fathers to serve as his council. He calls these men Patricians: they are fathers of Rome, not only because they care for their own legitimate citizen-sons but because they have a fatherly care for Rome and all its people. They are also its elders, and are therefore known as Senators. Romulus thereby inaugurates a system of government and social hierarchy based on the patron-client relationship.

Rome draws exiles, refugees, the dispossessed, criminals and runaway slaves. The city expands its boundaries to accommodate them; five of the seven hills of Rome are settled: the Capitoline Hill, the Aventine Hill, the Caelian Hill, the Quirinal Hill, and the Palatine Hill. As most of these immigrants are men, Rome finds itself with a shortage of marriageable women.

At the suggestion of his grandfather Numitor, Romulus holds a solemn festival in honor of Neptune (according to another tradition the festival was held in honor of the God Consus) and invites the neighboring Sabines and Latins to attend; they arrive en masse, along with their daughters. The Sabine and Latin women who happen to be virgins - 683 according to Livy - are kidnapped and brought back to Rome where they are forced to marry Roman men.

The Sabines, though a numerous and war-like people, found themselves bound by precious hostages, and fearing for their daughters, they sent ambassadors with reasonable and moderate demands that Romulus should give back their maidens, disavow his deed of violence, and then, by persuasion and legal enactment, establish a friendly relationship between the two peoples. But Romulus would not surrender the maidens, and demanded that the Sabines should allow marriage with the Romans, whereupon they all held long deliberations and made extensive preparations for war.

While most of the Sabines were still busy with their preparations, the people Sabines of a few cities banded together against the Romans, and in a battle which ensued, they were defeated, and surrendered to Romulus their cities, their territory to be divided, and themselves to be transported to Rome. Romulus distributed among the citizens all the territory thus acquired, excepting that which belonged to the parents of the ravished maidens; this he suffered its owners to keep for themselves.

This enraged the Sabines, and in response appointed Titus Tatius as the supreme commander-in-chief of all the Sabines, and he marched his army on Rome. The city was difficult of access, having as its fortress the Capitoline Hill, on which a guard had been stationed, with a man named Tarpeius as its captain.

But Tarpeia, a daughter of the commander, betrayed the citadel to the Sabines, having set her heart on the golden armlets which she saw them wearing, and she asked as payment for her treachery that which they wore on their left arms. Tatius agreed to this, whereupon she opened one of the gates by night and let the Sabines in.

Once inside, Tatius ordered his Sabines, mindful of their agreement, to begrudge the girl anything they wore on their left arms. Tatius was first to take from his arm not only his armlet, but at the same time his shield, and cast them upon her. All his men followed his example, and the girl was smitten by the gold and buried under the shields, and died from the number and weight of them.

With the Sabines controlling the Capitoline Hill, Romulus angrily challenged them to open battle, and Tatius boldly accepted. The Sabines marched down the Capitoline and battled the Romans between the hills in a swampy area which would one day become the Roman Forum.

The Sabines overran the Romans and the Romans were forced back behind the very walls of Rome upon the Palatine Hill. From behind the walls, the Romans began to flee the battle. Romulus bowed down and prayed to Jupiter and the Romans rallied back to Romulus and made a stand. Later, on the very spot where Romulus prayed, a temple to Jupiter Stator was built - stator meaning 'the stayer'.

Romulus led the Romans on and they drove the Sabines back to the point where the Temple to Vesta would later stand.

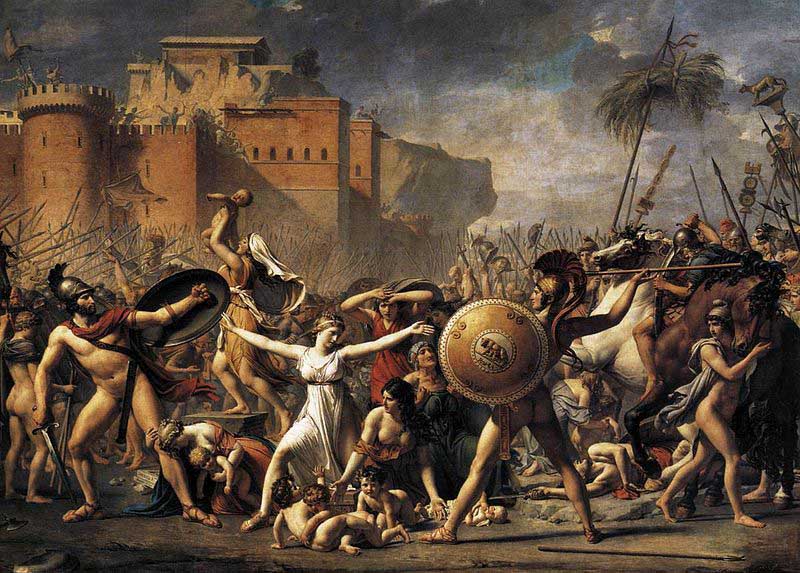

Here, as the Romans and Sabines were preparing to renew the battle, they were stopped by the sight of the ravished daughters of the Sabines rushing from the city of Rome through the infantry and the dead bodies.

The Sabine women ran up to their husbands and their fathers, some carrying young children in their arms. Both armies were so moved to compassion, they drew apart to give the women place between the battle lines. The Sabine women begged their Roman husbands and their Sabine fathers and brothers to accept one another and live as one nation.

With sorrow running through the ranks, a truce was made and the leaders held a conference. It was decided that both Romulus and Tatius would rule as joint kings of the Romans, including the newly added Sabines.Rome doubled in its size.

From the new Sabine citizens, 100 new noble men were selected to become Patricians and joined the ranks of the Senate. The legions were doubled in size, from 3000 infantry and 300 cavalry to 6000 infantry and 600 cavalry (roughly the same numbers as the classical Roman legion). The people, too, were organized into three voting tribes.

The first was called the Ramnenes, from Romulus, the second Tatienses, from Tatius; and the third Lucerenses, from the grove into which many betook themselves for refuge, when a general asylum was offered, and then became citizens of Rome, with each tribe being led by a Tribune.

These three tribes made up the Curiate Assembly, one of Rome’s oldest legislative assemblies. The cultures of the Romans and Sabine also combined in this union. The Sabines adopted the Roman calendar, and the Romans adopted the oblong shield and armor of the Sabines.

Romulus and Tatius rule jointly for five years and subdue the Alban colony of the Camerini. Then Tatius shelters some allies who have illegally plundered the Lavinians, and murders ambassadors sent to seek justice. Romulus and the Senate decide that Tatius should go to Lavinium to offer sacrifice and appeased his offence. At Lavinium, Tatius is assassinated and Romulus becomes sole king.

As king, Romulus holds authority over Rome's armies and judiciary. He organizes Rome's administration according to tribe; one of Latins (Ramnes), one of Sabines (Titites), and one of Luceres. Each elects a tribune to represented their civil, religious, and military interests. The tribunes are magistrates of their tribes, perform sacrifices on their behalf, and command their tribal levies in times of war.

Romulus divides each tribe into ten curiae to form the Comitia Curiata. The thirty curiae derive their individual names from thirty of the kidnapped Sabine women.

The individual curiae are further divided into ten gentes, held to form the basis for the nomen in the Roman naming convention. Proposals made by Romulus or the Senate are offered to the Curiate assembly for ratification; the ten gentes within each curia cast a vote. Votes are carried by whichever gens has a majority.

Romulus forms a personal guard called the Celeres; these are three hundred of Rome's finest horsemen. They are commanded by a tribune of the Ramnes; in one version of the founding tale, Celer killed Remus and helped Romulus found the city of Rome. The provision of a personal guard for Romulus helps justify the Augustan development of a Praetorian Guard, responsible for internal security and the personal safety of the Emperor. The relationship between Romulus and his Tribune resembles the later relation between the Roman Dictator and his Magister Equitum. Celer, as the Celerum Tribune, occupies the second place in the state, and in Romulus' absence has the rights of convoking the Comitia and commanding the armies.

For more than two decades, Romulus wages wars and expands Rome's territory. He subdues Fidenae, which has seized Roman provisions during a famine, and founds a Roman colony there. Then he subdues the Crustumini, who have murdered Roman colonists in their territory. The Etruscans of Veii protest the presence of a Roman garrison at Fidenae, and demand the return of the town to its citizens. When Romulus refuses, they confront him in battle and are defeated. They agree to a hundred year truce and surrender fifty noble hostages: Romulus celebrates his third and last triumph.

When Romulus' grandfather Numitor dies, the people of Alba Longa offer him the crown as rightful heir. Romulus adapts the government of the city to a Roman model. Henceforth, the citizens hold annual elections and choose one of their own as Roman governor.

In Rome, Romulus begins to show signs of autocratic rule. The Senate becomes less influential in administration and lawmaking; Romulus rules by edict. He divides his conquered territories among his soldiers without Patrician consent. Senatorial resentment grows to hatred.

Romulus's life ended in the 38th year of his reign, with a supernatural disappearance, if he was not slain by the Senate. Plutarch Life of Numa Pompilius tells the legend with a note of skepticism:"It was the thirty-seventh year, counted from the foundation of Rome, when Romulus, then reigning, did, on the fifth day of the month of July, called the Caprotine Nones, offer a public sacrifice at the Goat's Marsh, in presence of the senate and people of Rome.

Suddenly the sky was darkened, a thick cloud of storm and rain settled on the earth; the common people fled in affright, and were dispersed; and in this whirlwind Romulus disappeared, his body being never found either living or dead.

A foul suspicion presently attached to the patricians, and rumors were current among the people as if that they, weary of kingly government, and exasperated of late by the imperious deportment of Romulus towards them, had plotted against his life and made him away, that so they might assume the authority and government into their own hands.

This suspicion they sought to turn aside by decreeing divine honors to Romulus, as to one not dead but translated to a higher condition. And Proculus, a man of note, took oath that he saw Romulus caught up into heaven in his arms and vestments, and heard him, as he ascended, cry out that they should hereafter style him by the name of Quirinus."

At all events the story got about, though in veiled terms; but it was not important, as awe, and admiration for Romulus's greatness, set the seal upon the other version of his end, which was, moreover, given further credit by the timely action of a certain Julius Proculus, a man, we are told, honored for his wise counsel on weighty matters. The loss of the king had left the people in an uneasy mood and suspicious of the senators, and Proculus, aware of the prevalent temper, conceived the shrewd idea of addressing the Assembly. Romulus, he declared, the father of our City descended from heaven at dawn this morning and appeared to me.

In awe and reverence I stood before him, praying for permission to look upon his face without sin. "Go," he said, "and tell the Romans that by heaven's will my Rome shall be capital of the world. Let them learn to be soldiers. Let them know, and teach their children, that no power on earth can stand against Roman arms." Having spoken these words, he was taken up again into the sky." (Livy, 1.16, trans. A. de Selincourt, The Early History of Rome, 34-35)

As the god Quirinus, Romulus joined Jupiter and Mars as Quirinus in the Archaic Triad. Quirinus was depicted as beared warrior in both religious and battle clothing wielding a spear, thus he is viewed a god of war and as the strength of the Roman people, but more importantly, as the deified likeness of the city of Rome itself. Quirinus received a Flamen Maiores called the Flamen Quirinalis, who over saw his worship and rituals. The Romans even called themselves Quirites in his honor.

The exact date of Romulus and Remus's birth is unknown. Some writing, including those from Plutarch, say that Romulus was 54 years old at his death in 717 BC. If this is true, Romulus and Remus would have been born sometime in the year 771 BC. This also means that Romulus and Remus began the founding of Rome at the age of 18.

The mythic theme of twins is deep-seated in Mediterranean mythology: compare Castor and Polydeuces (the Dioscuri) of Greece, and Amphion and Zethus of Thebes.

One could compare the story of Romulus and Remus to Moses and Perseus - babies being placed in cradles and set afloat in body of water to find their destinies. This is of course all myth and metaphor and linked to Ancient Alien Theory.

Romulus was succeeded by ....

ALPHABETICAL INDEX OF ALL FILES