Judaism is a set of beliefs and practices originating in the Hebrew Bible, also known as the Tanakh, and explored in later texts such as the Talmud. Jews consider Judaism to be the expression of the covenantal relationship God developed with the Children of Israel - originally a group of twelve tribes claiming descent from the Biblical patriarch Jacob - and later, the Jewish people. According to most branches, God revealed his laws and commandments to Moses on Mount Sinai in the form of both the Written and Oral Torah. However, Karaite Judaism maintains that only the Written Torah was revealed, and liberal movements such as Humanistic Judaism may be nontheistic.

Judaism claims a historical continuity spanning more than 3000 years. It is one of the oldest monotheistic religions, and the oldest to survive into the present day. Its texts, traditions and values have inspired later Abrahamic religions, including Christianity, Islam and the Baha'i Faith. Many aspects of Judaism have also directly or indirectly influenced secular Western ethics and civil law.

Jews are an ethnoreligious group that includes those born Jewish and converts to Judaism. In 2007, the world Jewish population was estimated at 13 million, of which about 40% reside in Israel and 40% in the United States. The largest Jewish religious movements are Orthodox Judaism, Conservative Judaism and Reform Judaism. A major source of difference between these groups is their approach to Jewish law.

Orthodox and Conservative Judaism maintain that Jewish law should be followed, with Conservative Judaism promoting a more "modern" interpretation of its requirements than Orthodox Judaism. Reform Judaism is generally more liberal than these other two movements, and its typical position is that Jewish law should be viewed as a set of general guidelines rather than as a list of restrictions whose literal observance is required of all Jews.

Historically, special courts enforced Jewish law; today, these courts still exist but the practice of Judaism is mostly voluntary. Authority on theological and legal matters is not vested in any one person or organization, but in the sacred texts and the many rabbis and scholars who interpret these texts.

In the beginning...Twelve Israelite tribes came to Canaan from Mesopotamia.

1900 BCE - Abraham of Ur (present day Lebanon), the forefather of Judaism, rejects polytheism (worship of multiple gods) and begins the tradition of monotheism (the worship of one God). According to the Bible, God promises Abraham that he will make his family one great nation. Under God's direction, he and his family settle in the land of Israel.

1750 BCE- As a result of famine, Abraham's great-grandchildren leave Israel and settle in Egypt. After living in this country for many years, they are enslaved by the pharoah (Egyptian king).

1450 BCE- God forces the pharaoh to free Abraham's descendants, the Jews, from slavery. Under God's direction, Moses leads the Jews out of Egypt. After many years of wandering in the desert, they reach the land of Israel.

1410-1050 BCE- The Jews settle in the land of Israel. There, they divide into twelve separate tribes, each of which is led by a judge.

1050-933 BCE- Saul, the first king of Israel, unites the twelve tribes. David, who succeeded Saul as king, both extends and strengthens the kingdom of Israel. During his reign, Solomon, David's son, builds the Holy Temple.

928 BCE- The Jews revolt against the despotic rule of Saul's son. Subsequently, the kingdom of Israel splits into two: Israel and Judah.

722 BCE- After Solomon's death, the kingdom was divided into the kingdom of Israel and the kingdom of Judah. Both kingdoms were caught in the middle of the war between the great powers of Egypt and Assyria, which eventually destroyed Israel.

586 BCE- The Babylonians conquer the kingdom of Judah and destroy the Temple. Many Jews are forced to move to Babylonia where they build new places of worship (synagogues).

538 BCE- A new Babylonian king allows the Jews to return to Judah and rebuild the Temple. While many do return, a significant number remain in Babylonia.

332 BCE- Judah is conquered by the Greek Empire. Consequently, some Jews adopt Greek customs and religion.

168-164 BCE- Under the leadership of the Hasmoneans (particularly Judah Maccabee) , the Judeans successfully revolt against the Greek-Syrian king Antiochus. for a short period, Judah is free from external control.

63 BCE- The Roman Empire conquers Judah.

30- The Romans execute Jesus Christ, who was the leader of a small Jewish sect. Jesus's followers abandon Judaism and spread the Christian faith throughout the Roman Empire.

66-73- The Jews organize a revolt against Roman rule which fails miserably. In response, the Romans burn the Second Temple.

132-135- The Romans force the Jews to leave Jerusalem and forbid them from practicing their religion. Jewish worship continues in secret, however.

200s - The Jews continued to practice their religion illegally under Roman rule. Afraid that the laws of the Torah would be forgotten, the Rabbis wrote them down in the Mishnah. Babylonia becomes the major center of Jewish activity.

400s- Numerous Jewish academies are built in Babylonia by a Jewish leader known as the "exilarch." In 495 CE, the Babylonian Talmud is written down.

622- Muhammad initiate the religion of Islam in Arabia.

740-970 - Judaism spreads to Russia where the kingdom of Khazar becomes Jewish.

950-1391- A large Jewish community develops in Spain, where Jews experience a high degree of freedom under Christian and Muslim rulers.

950-1100- Jews settle in England, France, and Germany. During this time, many developments occurred in the area of Jewish study. Maimonides, for example, modernized Bible and Mishnah study.

1096-1320- Many Jews are killed during the Crusades. Some Jews are able to escape to Poland.

1200-1400- Jewish persecution continues in Western Europe. In 1290, Jews are expelled from England because they are too poor to pay taxes.

1348-1349- Many people blame the Jews for the Black Plague, which kills thousands in Europe. Consequently, Jews are expelled from many countries. Jewish immigration to Poland increases.

1300-1492- Oppression grows in Spain. In 1492, the same date which Columbus discovers the New World, Jews are ordered to leave Spain. Some Jews, known as Marranos, remain in Spain and continue to practice their religion in secret.

1500-1600- Spanish and Portuguese Jews immigrate to Italy, the Turkish Empire (particularly Palestine), North Africa, and the New World. Beginning in the 16th century, most Jews in Europe were forced to live in walled enclosures, where they were locked in at night, And had to wear badges identifying themselves as Jews when they were outside the walls. The Jewish quarter of Venice became known as the Ghetto, and eventually all these communities were called ghettos.

During the 16th century, many Jews settled in the Netherlands, where they were able to formally practice their religion again. Members of this group later founded successful Jewish communities in England as well.

1400-1648- Jews live peacefully in Poland where they work primarily as merchants artisans, and innkeepers. There, they are governed by the Jewish Council of Four Lands.

1648-1658- The Cossacks destroy 700 Jewish communities in Polish Russia. Many Jews are expelled from the region.

1500-1700- The Marranos move to Holland and France, where they are permitted to practice their religion freely. Jews also begin to return to England.

1750s- A new sect of Judaism known as Hasidism emerges in Eastern Europe. Commerce and industry flourish in Western Europe and some Jews become very prosperous. It thrived despite disapproval from the mainstream rabbinate.

1787- The Constitution of the United States of America promises religious freedom to all individuals. France follows the American lead and provides equal rights to Jews.

1791- In France in , after the French Revolution, Jews were granted citizenship and Napoleon I abolished ghettos in the countries he conquered. In 1815, Jews lost their rights in Germany, leading to the rise of anti-Semitism that lasts to this day. Equal rights were later granted Jews in the Netherlands, Great Britain and the United States, although discrimination continued. When Poland was annexed in the late 18th century, Polish Jews came under Russian rule. Catherine, empress of Russia, formed the Pale of Settlement in 1791, which restricted the places where Jews could live.

1800-1900- The concept of equal rights continue to spread throughout Western Europe. Consequently, Jews living in that region begin to enjoy more religious freedom. In Eastern Europe, however, there are numerous attacks on Jewish communities (pogroms). Reflecting in part these new found secular freedoms, the Reform movement emerges in Germany.

1804- In Russia, Jews were constantly persecuted and were only allowed to live in Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia and the Ukraine. Pogroms (organized persecution and massacre of Jews by the government) began in 1881, which led to many Jews relocating to western Europe, Latin America, Palestine and the United States.

1867- The Canadian Confederation is established.

1882- The Temple Emanu-El, the first Reform Judaism congregation in Montreal, is established.

1890s- The Conservative Judaism movement emerges in the United States. Dreyfus, a captain in the French army, is falsely accused of treason. Anti-Semitism increases throughout France and many Jews begin to actively support the idea of establishing a Jewish homeland in Palestine. In 1897, the first Zionist Congress takes place.

The movement of Zionism (dedicated to founding a Jewish state) was founded by Theodor Herzl in the late 1800s as a response to the Dreyfus Affair in France. Alfred Dreyfus, a French army officer, was falsely convicted of treason and imprisoned but was later exonerated when it was proved he was a victim of an anti-Semitic conspiracy. American Jewry provided relief for many of the east European Jews who suffered as a result of World War I.

1900-1914- The pogroms continue in Russia which results in further immigration to Western Europe, North America, and Palestine.

1914-1918- The first World War rages throughout Europe. Great Britain issues the Balfour Declaration (1917) which states that the British government "views with favor" the building of a Jewish home land in Palestine. Consequently, Jewish immigration to this region increases.

After the war, British agents made conflicting promises concerning Palestine to Arabs and Jews, which led to anti-Jewish riots in Palestine in 1920 and 1929. In 1929, leading non-Zionists joined with Zionists to found the Jewish Agency to help Jews settle in Palestine, since the western nations (including the United States) had imposed rigid immigration quotas.

After World War I, anti-Semitism grew in Europe, especially in Russia and Germany, leading to eventual official government policies of anti-Semitism in those countries.

1933- The Nazi party takes power in Germany. The Jews are blamed for the country's misfortunes and are placed in concentration camps.

1939-1945 - The Second World War rages. Hitler implemented "The Final Solution," the extermination of all Jews. In the Nazi concentration camps, more than six million Jews were tortured, gassed, starved or otherwise killed about one-third of the world's Jewish population. The Nazis conquer most of Europe, destroying much of the Jewish population in each country. In total 6 million Jews are killed in the Holocaust.

1948 - The State of Israel is established. Israel has since fought five wars against Arab states to keep its independence. In the United States, anti-Semitism has lessened in the post-World War II period, but it still exists in many places. America now has a Jewish population of approximately five million.

It is history that provides the clue to an understanding of Judaism, for its primal affirmations appear in early historical narratives. Many contemporary scholars agree that although the biblical (Old Testament) tales report contemporary events and activities, they do so for essentially theological reasons. Such a distinction, however, would have been unacceptable to the authors, for their understanding of events was not superadded to but was contemporaneous with their experience or report of them.

For them, it was primarily within history that the divine presence was encountered. God's presence was also experienced within the natural realm, but the more immediate or intimate disclosure occurred in human actions.Although other ancient communities saw a divine presence in history, this was taken up in its most consequent fashion within the ancient Israelite community and has remained, through many developments, the focus of its descendants' religious affirmations.

It is this particular claim--to have experienced God's presence in human events--and its subsequent development that is the differentiating factor in Jewish thought. As ancient Israel believed itself through its history to be standing in a unique relationship to the divine, this basic belief affected and fashioned its life-style and mode of existence in a way markedly different from groups starting with a somewhat similar insight. The response of the people Israel to the divine presence in history was seen as crucial not only for itself but for all mankind.

Further, God had--as person--in a particular encounter revealed the pattern and structure of communal and individual life to this people. Claiming sovereignty over the people because of his continuing action in history on its behalf, he had established a berit ("covenant") with it and had required from it obedience to his Torah (teaching). This obedience was a further means by which the divine presence was made manifest--expressed in concrete human existence. The corporate life of the chosen community was thus a summons to the rest of mankind to recognize God's presence, sovereignty, and purpose--the establishment of peace and well-being in the universe and in mankind.

History, moreover, disclosed not only God's purpose but also manifested man's inability to live in accord with it. Even the chosen community failed in its obligation and had, time and again, to be summoned back to its responsibility by divinely called spokesmen--the prophets--who warned of retribution within history and argued and reargued the case of affirmative human response. Israel's role in the divine economy and thus Israel's particular culpability were dominant themes sounded against the motif of fulfillment, the ultimate triumph of the divine purpose, and the establishment of divine sovereignty over all mankind.

Nature and Characteristics

In nearly 4,000 years of historical development, the Jewish people and their religion have displayed both a remarkable adaptability and continuity. In their encounter with the great civilizations, from ancient Babylonia and Egypt down to Western Christendom and modern secular culture, they have assimilated foreign elements and integrated them into their own socioreligious system, thus maintaining an unbroken line of ethnic and religious tradition. Furthermore, each period of Jewish history has left behind it a specific element of a Judaic heritage that continued to influence subsequent developments, so that the total Jewish heritage at any time is a combination of all these successive elements along with whatever adjustments and accretions are imperative in each new age.

The fundamental teachings of Judaism have often been grouped around the concept of an ethical (or ethical-historical) monotheism. Belief in the one and only God of Israel has been adhered to by professing Jews of all ages and all shades of sectarian opinion. By its very nature monotheism ultimately postulated religious universalism, although it could be combined with a measure of particularism. In the case of ancient Israel (see below Biblical Judaism [20th-4th century BCE]), particularism took the shape of the doctrine of election; that is, of a people chosen by God as "a kingdom of priests and a holy nation" to set an example for all mankind. Such an arrangement presupposed a covenant between God and the people, the terms of which the chosen people had to live up to or be severely punished.

As the 8th-century-BCE prophet Amos expressed it: "You only have I known of all the families of the earth; therefore I will punish you for all your iniquities." Further, it was a concept that combined with the messianic idea, according to which, at the advent of the Redeemer, all nations would see the light, give up war and strife, and follow the guidance of the Torah (divine guidance, teaching, or law) emanating from Zion (a hill in Jerusalem that has a special spiritual significance). With all its variations in detail, messianism has, in one form or another, permeated Jewish thinking throughout the ages and, under various guises, has colored the outlook of many secular-minded Jews (see also eschatology).

Law became the major instrumentality by which Judaism was to bring about the reign of God on earth. In this case law meant not only what the Romans called jus (human law) but also fas, the divine or moral law that embraces practically all domains of life. The ideal, therefore, as expressed in the Ten Commandments, was a religioethical conduct that involved ritualistic observance as well as individual and social ethics, a liturgical-ethical way constantly expatiated on by the prophets and priests, rabbinic sages, and philosophers. Such conduct was to be placed in the service of God, as the transcendent and immanent Ruler of the universe, and as such the Creator and propelling force of the natural world, and also as the One giving guidance to history and thus helping man to overcome the potentially destructive and amoral forces of nature.

According to Judaic belief, it is through the historical evolution of man, and particularly of the Jewish people, that the divine guidance of history constantly manifests itself and will ultimately culminate in the messianic age. Judaism, whether in its "normative" form or its sectarian deviations, never completely departed from this basic ethical-historical monotheism.

The division of the millennia of Jewish history into periods--a procedure frequently dependent on individual preferences--has not been devoid of theological or scholarly presuppositions. The Christian world long believed that until the rise of Christianity the history of Judaism was but a "preparation for the Gospel" (preparatio evangelica) followed by the "manifestation of the Gospel" (demonstratio evangelica) as revealed by Christ and the Apostles. This formulation could be theologically reconciled with the assumption that Christianity had been preordained even before the creation of the world.

On the other hand, 19th-century biblical scholars moved the decisive division back into the period of the Babylonian Exile and restoration of the Jews to Judah (6th-5th centuries BCE). They asserted that after the first fall of Jerusalem (586 BCE) the ancient "Israelitic" religion gave way to a new form of the "Jewish" faith, or Judaism, as formulated by Ezra the Scribe and his school (5th century BCE). A German historian, Eduard Meyer, in 1896 published Die Entstehung des Judentums ("The Origin of Judaism"), in which he placed the origins of Judaism in the Persian period (see below Biblical Judaism [20th-4th century BCE]) or the days of Ezra and Nehemiah (5th century BCE) and actually attributed to Persian imperialism an important role in shaping the new emergent Judaism.

These theories have been discarded by most scholars, however, in the light of a more comprehensive knowledge of the ancient Middle East and the abandonment of a theory of gradual evolutionary development that was dominant at the beginning of the 20th century. Most Jews share a long-accepted notion that there never was a real break in continuity and that Mosaic-prophetic-priestly Judaism was continued, with but few modifications, in the work of the Pharisaic and rabbinic sages (see below Rabbinic Judaism [2nd-18th century]) well into the modern period. Even today the various Jewish groups, whether Orthodox, Conservative, or Reform, all claim direct spiritual descent from the Pharisees and the rabbinic sages. In actual historical development, however, many deviations have occurred from so-called normative or rabbinic Judaism.

In any case, the history of Judaism here is viewed as falling into the following major periods of development: biblical Judaism (c. 20th-4th century BCE), Hellenistic Judaism (4th century BCE-2nd century CE), rabbinic Judaism (2nd-18th century CE), and modern Judaism (c. 1750 to the present). (S.W.B.)

The Ancient Middle Eastern Setting

The family of the Hebrew patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob) is depicted in the Bible as having had its chief seat in the northern Mesopotamian town of Harran--then (mid-2nd millennium BCE) belonging to the Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni. From there Abraham, the founder of the Hebrew people, is said to have migrated to Canaan (comprising roughly the region of modern Israel and Lebanon)--throughout the biblical period and later ages a vortex of west Asian, Egyptian, and east Mediterranean ethnoculture.

Thence the Hebrew ancestors of the people of Israel (named after the patriarch Jacob, also called Israel) migrated to Egypt, where they lived in servitude, and a few generations later returned to occupy part of Canaan. The Hebrews were seminomadic herdsmen and occasionally farmers, ranging close to towns and living in houses as well as tents.

The initial level of Israelite culture resembled that of its surroundings; it was neither wholly original nor primitive. The tribal structure resembled that of West Semitic steppe dwellers known from the 18th-century-BCE tablets excavated at the north central Mesopotamian city of Mari; their family customs and law have parallels in Old Babylonian and Hurro-Semite law of the early and middle 2nd millennium.

The conception of a messenger of God that underlies biblical prophecy was Amorite (West Semitic) and found in the tablets at Mari. Mesopotamian religious and cultural conceptions are reflected in biblical cosmogony, primeval history (including the Flood story in Gen. 6:9-8:22), and law collections. The Canaanite component of Israelite culture consisted of the Hebrew language and a rich literary heritage--whose Ugaritic form (which flourished in the northern Syrian city of Ugarit from the mid-15th century to about 1200 BCE) illuminates the Bible's poetry, style, mythological allusions, and religiocultic terms.

Egypt provides many analogues for Hebrew hymnody and wisdom literature. All the cultures among which the patriarchs lived had cosmic gods who fashioned the world and preserved its order, including justice; all had a developed ethic expressed in law and moral admonitions; and all had sophisticated religious rites and myths.

Though plainer when compared with some of the learned literary creations of Mesopotamia, Canaan, and Egypt, the earliest biblical writings are so imbued with contemporary ancient Middle Eastern elements that the once-held assumption that Israelite religion began on a primitive level must be rejected. Late-born amid high civilizations, the Israelite religion had from the start that admixture of high and low features characteristic of all the known religions of the area. Implanted on the land bridge between Africa and Asia, it was exposed to crosscurrents of foreign thought throughout its history.

Israelite tradition identified YHWH (by scholarly convention pronounced Yahweh), the God of Israel, with the Creator of the world, who had been known to and worshipped by men from the beginning of time. Abraham (perhaps 19th or 18th-17th centuries BCE) did not discover this God, but entered into a new covenant relation with him, in which he was promised the land of Canaan and a numerous progeny. God fulfilled that promise through the actions of the 13th-century-BCE Hebrew leader Moses: he liberated the people of Israel from Egypt, imposed Covenant obligations on them at Mt. Sinai, and brought them to the promised land.

Historical and anthropological studies present formidable objections to the continuity of YHWH worship from Adam (the biblical first man) to Moses, and the Hebrew tradition itself, moreover, does not unanimously support even the more modest claim of the continuity of YHWH worship from Abraham to Moses. Against it is a statement in chapter 6, verse 3, of Exodus that God revealed himself to the patriarchs not as YHWH but as El Shaddai--an epithet (of unknown meaning) the distribution of which in patriarchal narratives and Job and other poetical works confirms its archaic and unspecifically Israelite character.

Comparable is the distribution of the epithet El Elyon (God Most High). Neither of these epithets appears in postpatriarchal narratives (excepting the Book of Ruth). Other compounds with El are unique to Genesis: El Olam (God the Everlasting One), El Bethel (God Bethel), and El Ro'i (God of Vision). An additional peculiarity of the patriarchal stories is their use of the phrase "God of my [your, his] father."

All of these epithets have been taken as evidence that patriarchal religion differed from the worship of YHWH that began with Moses.

A relation to a patron god was defined by revelations starting with Abraham (who never refers to the God of his father) and continuing with a succession of "founders" of his worship. Attached to the founder and his family, as befits the patron of wanderers, this unnamed deity (if indeed he was one only) acquired various Canaanite epithets (El, Elyon, Olam, Bethel, qone eretz [possessor of the Land]) only after their immigration into Canaan.

Whether the name of YHWH was known to the patriarchs is doubtful. It is significant that while the epithets Shaddai and El occur frequently in pre-Mosaic and Mosaic-age names, YHWH appears as an element only in the names of Yehoshua' (Joshua) and perhaps of Jochebed--persons who were closely associated with Moses.

The Egyptian Sojourn

According to Hebrew tradition, a famine caused the migration to Egypt of the band of 12 Hebrew families that later made up a tribal league in the land of Israel. The schematic character of this tradition does not impair the historicity of a migration to Egypt, an enslavement by Egyptians, and an escape from Egypt under an inspired leader by some component of the later league of Israelite tribes. To disallow these events would make their centrality as articles of faith in the later religious beliefs of Israel inexplicable.

Tradition gives the following account of the birth of the nation. At the Exodus from Egypt (13th century BCE), YHWH showed his faithfulness and power by liberating Israel from bondage and punishing their oppressors with plagues and drowning at the sea. At Sinai, he made Israel his people and gave them the terms of his Covenant, regulating their conduct toward him and each other so as to make them a holy nation. After sustaining them miraculously during their 40-year wilderness trek, he enabled them to take the land that he had promised to their fathers, the patriarchs. Central to these events is God's apostle, Moses, who was commissioned to lead Israel out of Egypt, mediate God's Covenant to them, and bring them to Canaan.

Behind the legends and the multiform law collections, a historical figure must be posited to whom the legends and the legislative activity could be attached. And it is precisely Moses' unusual combination of roles that makes him credible as a historical figure. Like Muhammad at the birth of Islam, Moses fills oracular, legislative, executive, and military functions. The main institutions of Israel are his creation: the priesthood and the sacred shrine, the Covenant and its rules, the administrative apparatus of the tribal league. Significantly, though Moses is compared to a prophet in various texts in the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible), he is never designated as one--the term being evidently unsuited for so comprehensive and unique a figure.

The distinctive features of Israelite religion appear with Moses. The proper name of Israel's God, YHWH, was revealed and interpreted to Moses as meaning ehye asher ehye--an enigmatic phrase (literally meaning "I am/shall be what I am/shall be") of infinite suggestiveness. The Covenant, defining Israel's obligations, is ascribed to Moses' mediation. Although it is impossible to determine what rulings go back to Moses, the Decalogue, or Ten Commandments, presented in chapter 20 of Exodus and chapter 5 of Deuteronomy, and the larger and smaller Covenant codes in Ex. 20:22-23:33; 34:11-26) are held by critics to contain early covenant law. From them, the following features may be noted: (1) The rules are formulated as God's utterances--i.e., expressions of his sovereign will. (2) They are directed toward, and often explicitly addressed to, the people at large; Moses merely conveys the sovereign's message to his subjects. (3) Publication being of the essence of the rules, the people as a whole are held responsible for their observance.

The liberation from Egypt laid upon Israel the obligation of exclusive loyalty to YHWH. This meant eschewing all other gods--including idols venerated as such--and the elimination of all magical recourses. The worship of YHWH was aniconic (without images); even such figures as might serve in his worship were banned--apparently owing to the theurgic overtones (the implication that through them men may influence or control the god by fixing his presence in a particular place and making him accessible). Though a mythological background lies behind some cultic terminology (e.g., "a pleasing odor to YHWH," "my bread"), sacrifice is rationalized as tribute or (in priestly writings) is regarded purely as a sacrament; i.e., as a material means of relating to God. Hebrew festivals also have no mythological basis; they either celebrate God's bounty (e.g., at the ingathering of the harvest) or his saving acts (e.g., the festival of unleavened bread, which is a memorial of the Exodus).

The values of life and limb, labour, and social solidarity are protected in the rules on relations between man and man. The involuntary perpetual slavery of Hebrews is abolished, and a seven-year limit is set on bondage. The humanity of slaves is defended: one who beats his slave to death is liable to death; if he maims a slave he must set the slave free. A murderer is denied asylum and may not ransom himself from death, while for deliberate and severe bodily injuries the lex talionis ("an eye for an eye" principle) is ordained. Harm to property or theft is punished monetarily, never by death.

Moral exhortations call for solidarity with the poor and the helpless, for brotherly assistance to fellows in need. Institutions are created (e.g., the sabbatical, or seventh, fallow year, in which land is not cultivated) to embody them in practice. Since the goal of the people was the conquest of a land, their religion had warlike features. Organized as an army (called "the hosts of YHWH" in Ex. 12:41), they encamped in a protective square around their palladium--the tent housing the ark in which the stone "tablets of the Covenant" rested. When journeying, the sacred objects were carried and guarded by the Levites (a tribe serving religious functions), whose rivals, the Aaronites, had a monopoly on the priesthood. God, sometimes called "the warrior," marched with the army; in war, part of the booty was delivered to his ministers.

The conquest of Canaan was remembered as a continuation of God's marvels at the Exodus. The Jordan River was split asunder, Jericho's walls fell at Israel's shout; the enemy was seized with divinely inspired terror; the sun stood still in order to enable Israel to exploit its victory. Such stories are not necessarily the work of a later age; they reflect rather the impact of these victories on the actors in the drama, who felt themselves successful by the grace of God.

A complex process of occupation, involving both battles of annihilation and treaty arrangements with the natives, has been simplified in the biblical account of Joshua's wars. Gradually, the unity of the invaders dissolved (most scholars believe that the invading element was only part of the Hebrew settlement in Canaan; other Hebrews, long since settled in Canaan from patriarchal times, then joined the invaders' covenant league). Individual tribes made their way with more or less success against the residue of Canaanite resistance. New enemies, Israel's neighbours to the east and west, appeared, and the period of the judges (leaders, or champions) began.

The Book of Judges, the main witness for the period, does not speak with one voice on the religious situation. Its editorial framework describes repeated cycles of apostasy, oppression, appeal to God, and relief through a Godsent champion. The premonarchic troubles (before the kingship of Saul; see below) caused by the weakness of the disunited tribes were thus accounted for by the covenantal sin of apostasy. The individual stories, however, present a different picture. Apostasy does not figure in the exploits of the judges Ehud, Deborah, Jephthah, and Samson; YHWH has no rival, and faith in him is periodically confirmed by the saviours he sends to rescue Israel from their neighbours.

This faith is shared by all the tribes; and it is owing to their common cult that a Levite from Bethlehem could serve first at an Ephraimite and later also at a Danite sanctuary. The religious bond, preserved by the common cult, was enough to enable the tribes to act more or less in concert under the leadership of elders or an inspired champion in time of danger or religious scandal.

To be sure, both written and archaeological testimonies point to the Hebrews' adoption of Canaanite cults--the Baal worship of Gideon's family and neighbours in Ophrah in Judges, chapter 6, is an example. The many cultic figurines (usually female) found in Israelite levels of Palestinian archaeological sites also give colour to the sweeping indictments of the framework of the Book of Judges. But these phenomena belonged to the private, popular religion; the national God, YHWH, remained one--Baal sent no prophets to Israel--though YHWH's claim to exclusive worship was obviously not effectual. Nor did his cult conform with later orthodoxy; Micah's idol in Judges, chapter 17, and Gideon's ephod (priestly or religious garment) were considered apostasies by the editor, in accord with the dogma that other than orthodoxy there is only apostasy--heterodoxy (nonconformity) being unrecognized and simply equated with apostasy.

To the earliest sanctuaries and altars honoured as patriarchal foundations--at Shechem, Bethel, Beersheba, and Hebron in Cisjordan (west of the Jordan); at Mahanaim, Penuel, and Mizpah in Transjordan (east of the Jordan)--were now added new ones at Dan, Shiloh, Ramah, Gibeon, and Gilgal, among others. A single priestly family could not operate all these establishments, and Levites rose to the priesthood; at private sanctuaries even non-Levites might be consecrated as priests.

The ark of the Covenant was housed in the Shiloh sanctuary, staffed by priests of the house of Eli, who traced their consecration back to Egypt. But the ark remained a portable palladium in wartime; Shiloh was not regarded as its final resting place. The law in Exodus, chapter 20, verses 24-26, authorizing a plurality of altar sites and the simplest forms of construction (earth and rough stone) suited the plain conditions of this period.

The Religiopolitical Problem

The loose, decentralized tribal league could not cope with the constant pressure of external enemies--camel-riding desert marauders who pillaged harvests annually or iron-weaponed Philistines (an Aegean people settling coastal Palestine c. 12th century BCE) who controlled key points in the hill country occupied by Israelites. In the face of such threats to the Israelites, local, sporadic, God-inspired saviours had to be replaced by a continuous central leadership that could mobilize the forces of the entire league and create a standing army.

Two attitudes were distilled in the crisis, one conservative and antimonarchic, the other progressive and promonarchic.

The conservative appears first in Gideon's refusal, in Judges, chapter 8, verse 23, to found a dynasty: "I will not rule you," he tells the people, "my son will not rule over you; YHWH will!" This theocratic view pervades one of the two contrasting accounts of the founding of the monarchy fused in chapters 8-12 of the First Book of Samuel: the popular demand for a king was viewed as a rejection of the kingship of God, which was embodied in a series of inspired saviours from Moses and Aaron, through Jerubbaal, Bedan, and Jephthah, to Samuel. The other account depicts the monarchy as a gift of God, designed to rescue his people from the Philistines (I Sam. 9:16). Both accounts represent the seer-judge Samuel as the key figure in the founding of Israel's monarchy, and it is not unlikely that the two attitudes struggled in his breast.

The Benjaminite Saul was made king (c. 1020 BCE) by divine election and by popular acclamation after his victory over the Ammonites (a Transjordanian Semitic people), but his career was clouded by conflict with Samuel, the major representative of the old order. Saul's kingship was bestowed by Samuel and had to be accommodated to the ongoing authority of that man of God. The two accounts of Saul's rejection by God (through Samuel) involve his usurpation of the prophet's authority. King David, whose forcefulness and religiopolitical genius established the monarchy (c. 1000 BCE) on an independent spiritual footing, resolved the conflict.

The essence of the Davidic innovation was the idea that, in addition to divine election through Samuel and public acclamation, David had God's promise of an eternal dynasty (a conditional, perhaps earlier, and an unconditional, perhaps later, form of this promise exist in Psalms, 132 and II Samuel, chapter 7, respectively). In its developed form, the promise was conceived of as a covenant with David, parallelling the Covenant with Israel and instrumental in the latter's fulfillment; i.e., that God would channel his benefactions to Israel through the chosen dynasty of David. With this new status came the inviolability of the person of God's anointed (a characteristically Davidic idea) and a court rhetoric--adapted from pagan models--in which the king was styled "the [firstborn] son of God." An index of the king's sanctity was his occasional performance of priestly duties. Yet the king's mortality was never forgotten--he was never deified; prayers and hymns might be said on his behalf, but they were never addressed to him as a god.

David captured the Jebusite stronghold of Jerusalem and made it the seat of a national monarchy (Saul had never moved the seat of his government from his home town, the Benjaminite town of Gibeah, about three miles north of Jerusalem). Then, fetching the ark from an obscure retreat, David installed it in his capital, asserting his royal prerogative (and obligation) to build a shrine for the national God--at the same time joining the symbols of the dynastic and the national covenants. This move of political genius linked the God of Israel, the chosen dynasty of David, and the chosen city of Jerusalem in a henceforth indissoluble union.

David planned to erect a temple to house the ark, but the tenacious tradition of the ark's portability in a tent shrine forced postponement of the project to his son Solomon's reign. As part of his extensive building operations, Solomon built the Temple on a Jebusite threshing floor, located on a hill north of the royal city, which David had purchased to mark the spot where a plague had been halted. The ground plan of the Temple--a porch with two free-standing pillars before it, a sanctuary, and an inner sanctum--followed Syrian and Phoenician sanctuary models. A bronze "sea" resting on bulls and placed in the Temple court has a Babylonian analogue. Exteriorly, the Jerusalem Temple resembled Canaanite and other Middle Eastern religious structures, but there were differences; e.g., no god image stood in the inner sanctum, but rather only the ancient ark and the new large cherubim (hybrid creatures with animal bodies, human or animal faces, and wings) whose wings covered it, symbolizing the presence of YHWH who was enthroned upon celestial cherubim.

Alongside a brief, ancient inaugural poem in I Kings, chapter 8, verses 12-13, an extensive (and, in its present form, later) prayer expresses the distinctively biblical view of the temple as a vehicle of God's providing for his people's needs. Since, strangely, no reference to sacrifice is made, not a trace appears of the standard pagan conception of the temple as a vehicle of man's providing for the gods.

That literature flourished under the aegis of the court is to be gathered from the quality of the preserved narrative of the reign of David, which gives every indication of having come from the hand of a contemporary eyewitness. The royally sponsored Temple must have had a library and a school attached to it (in accord with the universally attested practice of the ancient Middle East), among whose products were not only royal psalms but also such liturgical pieces intended for the common man as eventually found their way into the book of Psalms.

The latest historical allusions in the Torah literature (the Pentateuch) are to the period of the united monarchy; e.g., the defeat and subjugation of the peoples of Amalek, Moab, and Edom by Saul and David, in Numbers, chapter 24, verses 17-20. On the other hand, the polity reflected in the laws is tribal and decentralized, with no bureaucracy. Its economy is agricultural and pastoral, class distinctions apart from slave and free are lacking, and commerce and urban life are rudimentary. A premonarchic background is evident, with only rare explicit reflections of the later monarchy; e.g., in Deuteronomy, chapter 17, verses 14-20. The groundwork of the Torah literature may thus be supposed to have crystallized under the united monarchy.

It was in this period that the traditional wisdom cultivated among the learned in neighbouring cultures came to be prized in Israel. Solomon is represented as the author of an extensive literature comparable to that of other Eastern sages. His wisdom is expressly attributed to YHWH in the account of his night oracle at Gibeon (in which he asked not for power or riches but for wisdom), thus marking the adaptation to biblical thought of this common Middle Eastern genre. As set forth in Proverbs, chapter 2, verse 5, "It is YHWH who grants wisdom; knowledge and understanding are by his command." Patronage of wisdom literature is ascribed to the later Judahite king, Hezekiah, and the connection of wisdom with kings is common in extrabiblical cultures as well.

Domination of all of Palestine entailed the absorption of "the rest of the Amorites"--the pre-Israelite population that lived chiefly in the valleys and on the coast. Their impact on Israelite religion is unknown, though some scholars contend that a "royally sponsored syncretism" arose with the aim of fusing the two populations. That popular religion did not meet the standards of the biblical writers and that it incorporated pagan elements--and that such elements may have increased as a result of intercourse with the newly absorbed "Amorites"--is likely and required no royal sponsorship.

On the other hand, the court itself welcomed foreigners--Philistines, Cretans, Hittites, and Ishmaelites are named, among others--and made use of their service. Their effect on the court religion may be surmised from what is recorded concerning Solomon's many diplomatic marriages: foreign princesses whom Solomon married brought along with them the apparatus of their native cults, and the King had shrines to their gods built and maintained on the Mount of Olives. Such private cults, while indeed royally sponsored, did not make the religion of the people syncretistic.

Such compromise with the pagan world, entailed by the widening horizons of the monarchy, violated the sanctity of the holy land of YHWH and turned the king into an idolator in the eyes of zealots. Religious opposition, combined with grievances against the organization of forced labour for state projects, led to the secession of the northern tribes (headed by the Joseph tribes) after Solomon's death.

Jeroboam I (10th century BCE), the first king of the north (now called Israel, in contradistinction to Judah, the southern Davidic kingdom), appreciated the inextricable link of Jerusalem and its sanctuary with the Davidic claim to divine election to kingship over all Israel (the whole people, north and south). He therefore founded rival sanctuaries at Dan and at Bethel--ancient cult sites--and manned them with non-Levite priests whose symbol of YHWH's presence was a golden calf--a pedestal of divine images in ancient iconography and the equivalent of the cherubim of Jerusalem's Temple. He also moved the autumn ingathering festival one month ahead so as to foreclose celebration of this most popular of all festivals in common with Judah.

For the evaluation of Jeroboam's innovations and the subsequent official religion of the north down to the mid-8th century, one must rely almost exclusively on the Book of Kings (later divided into two books). This work has severe limitations as a source for religious history. The material of this book, in good part contemporary, is subjugated to a dogmatic historiography that regards the whole enterprise of the north as one long apostasy ending in a deserved disaster. The culmination of Kings' history with the exile of Judah shows its provenience to have been Judahite.

Yet the evaluation of Judah's official religion is subject to an equally dogmatic standard, namely, the royal adherence to the Deuteronomic rule of a single cult site. The author considered the Solomonic Temple to be the cult site chosen by God, according to Deuteronomy, chapter 12, the existence of which rendered all other sites illegitimate. Every king of Judah is judged according to whether or not he did away with all extra-Jerusalemite places of worship. (The date of this criterion may be inferred from the indifference toward it of all persons [e.g., the 9th-century-BCE prophets Elijah and Elisha and the Jerusalemite priest Jehoiada] prior to the late-8th-century-BCE Judahite king Hezekiah.)

Another serious limitation is the restriction of Kings' purview: excepting the Elijah-Elisha stories, it notices only the royally sponsored cult; notices of the popular religion are very few. From the mid-8th century the writings of the classical prophets, starting with Amos, set in. These take in the people as a whole, in contrast to Kings; on the other hand their interest in theodicy (justification of God) and their polemical tendency to exaggerate and generalize what they deem evil must be taken into consideration before approving their statements as sober history.

For a half-century after the north's secession (c. 922 BCE), the religious situation in Jerusalem was unchanged. The distaff side of the royal household perpetuated, and even augmented, the pagan cults. King Asa (reigned c. 908-867 BCE) is credited with a general purge, including the destruction of an image made for the goddess Asherah by the queen mother, granddaughter of an Aramaean princess. He also purged the qedeshim ("consecrated men"--conventionally rendered as "sodomites," or "male sacred prostitutes").

Foreign cults entered the north with the marriage of the 9th-century-BCE king Ahab to the Tyrian princess Jezebel. Jezebel brought with her a large entourage of sacred personnel to staff the temple of Baal and Asherah that Ahab built for her in Samaria, the capital of the northern kingdom of Israel. In all else, Ahab's orthodoxy was irreproachable, though others of his court may have joined the worship of the foreign princess.

That fierce opposition to the non-YWHW cults sprang up must be supposed in order to account for Jezebel's persecution of the prophets of YHWH, conduct untypical of a polytheist except in self-defense. Elijah's assertion that the whole country apostatized is a hyperbole based on the view that whoever did not actively fight Jezebel was implicated in her polluted cult. Such must have been the view of the prophets, whose fallen were the first martyrs to die for the glory of God. The quality of their opposition may be gauged by Elijah's summary execution of the foreign Baal cultists after they failed the test at Mt. Carmel, where they vied against him in a contest over whose god was truly God. A three-year drought (attested also in Phoenician sources), declared by Elijah to be punishment for the sin, must have done much to kindle the prophets' zeal.

To judge from the Elisha stories, the Baal worship in the capital city, Samaria, was not felt in the countryside. There the religious tone was set by the popular prophets and the prophetic companies ("the sons of the prophets") who attached themselves to them. In popular consciousness these men were wonder-workers--healing the sick and reviving the dead, foretelling the future, and helping to find lost objects.

To the biblical narrator they witness the working of God in Israel. Elijah's rage at the Israelite king Ahaziah's recourse to the pagan god Baalzebub, Elisha's cure of the Syrian military leader Naaman's leprosy, and anonymous prophets' directives and predictions in matters of peace and war all serve to glorify God. Indeed, the equation of Israel's prosperity with God's interest generated the issue of "true" and "false" prophecy that made its first appearance at this time.

That prophecy of success could turn out to be a snare is exemplified in a story of conflict between Micaiah, the lone 9th-century-BCE prophet of doom, and 400 unanimous prophets of victory who lured Ahab to his death. The poignancy of the issue is highlighted by Micaiah's acknowledgment that the 400 were also prophets of YHWH--but inspired by him deliberately with a "lying spirit."

The Emergence of the Literary Prophets

By the mid-8th century a hundred years of chronic warfare between Israel and Aram had finally ended--the Aramaeans having suffered heavy blows from the Assyrians. King Jeroboam II (8th century BCE) was able to undertake to restore the imperial sway of the north over its neighbour, and a prophecy of Jonah that he would extend Israel's borders from the Dead Sea to the entrance to Hamath (Syria) was borne out.

The well-to-do expressed their relief in lavish attentions to the institutions of worship and their private mansions. But the strain of the prolonged warfare showed in the polarization of society between the wealthy few who had profited from the war and the masses whom it had ravaged and impoverished. Dismay at the dissolution of Israelite society animated a new breed of prophets who now appeared--the literary or classical prophets, first of whom was Amos, an 8th-century-BCE Judahite who went north to Bethel.

That apostasy would set God against the community was an old conception of early prophecy; that violation of the sociomoral injunctions of the Covenant would have the same result was first proclaimed by Amos. Amos almost ignored idolatry, denouncing instead the corruption and callousness of the oligarchy and rulers. The religious exercises of such villains he proclaimed were loathsome to God; on their account Israel would be oppressed from the entrance to Hamath to the Dead Sea and exiled from its land.

The westward push of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the mid-8th century BCE soon brought Aram and Israel to their knees. In 733-732 Assyria took Gilead and Galilee from Israel and captured Aramaean Damascus; in 721 Samaria, the Israelite capital, fell. The northern kingdom sought to survive through alliances with Assyria and Egypt; its kings came and went in rapid succession.

The troubled society's malaise was interpreted by Hosea, a prophet of the northern kingdom (Israel), as a forgetting of God. As a result, in his view, all authority had evaporated: the king was scoffed at, priests became hypocrites, and pleasure seeking became the order of the day. The monarchy was godless; it put its trust in arms, fortifications, and alliances with the great powers. Salvation, however, lay in none of these but in repentance and reliance upon God.

Judah was subjected to such intense pressure to join an Israelite-Aramaean coalition against Assyria that its 8th-century-BCE king Ahaz chose to submit himself to Assyria in return for relief. Ahaz introduced a new Aramaean-style altar in the Jerusalem Temple and adopted other foreign customs that are counted against him in the book of Kings. It was at this time that Isaiah prophesied in Jerusalem.

At first (under Uzziah, Ahaz' prosperous grandfather), his message focussed on the corruption of Judah's society and religion, stressing the new prophetic themes of indifference to God (which went hand in hand with a thriving cult) and the fateful importance of social morality.

Under Ahaz the political crisis evoked Isaiah's appeals for trust in God, with the warning that the "hired razor from across the Euphrates" would shave Judah clean as well. Isaiah interpreted the inexorable advance of Assyria as God's chastisement; Assyria was "the rod of God's wrath." But, since Assyria ignored its mere instrumentality and exceeded in an insolent manner its proper function, God, when he finished his purgative work, would break Assyria on Judah's mountains. Then the nations of the world, who had been subjugated by Assyria, would recognize the God of Israel as the lord of history. A renewed Israel would prosper under the reign of an ideal Davidic king, all men would flock to Zion (the hill symbolizing Jerusalem) to learn the ways of YHWH and submit to his adjudication, and universal peace would prevail (see also eschatology).

The prophecy of Micah (8th century BCE), also a Judahite, was contemporary with that of Isaiah and touched on similar themes (e.g., the vision of universal peace is found in both their books). Unlike Isaiah, however, who believed in the inviolability of Jerusalem, Micah shocked his audience with the announcement that the wickedness of its rulers would cause Zion to become a plowed field, Jerusalem a heap of ruins, and the Temple mount a wooded height. Moreover, from the precedence of social morality over the cult, Micah drew the extreme conclusion that the cult had no ultimate value and that God's requirement of men can be summed up as "to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God."

Comparable is the distribution of the epithet El Elyon (God Most High). Neither of these epithets appears in postpatriarchal narratives (excepting the Book of Ruth). Other compounds with El are unique to Genesis: El Olam (God the Everlasting One), El Bethel (God Bethel), and El Ro'i (God of Vision). An additional peculiarity of the patriarchal stories is their use of the phrase "God of my [your, his] father." All of these epithets have been taken as evidence that patriarchal religion differed from the worship of YHWH that began with Moses.

A relation to a patron god was defined by revelations starting with Abraham (who never refers to the God of his father) and continuing with a succession of "founders" of his worship. Attached to the founder and his family, as befits the patron of wanderers, this unnamed deity (if indeed he was one only) acquired various Canaanite epithets (El, Elyon, Olam, Bethel, qone eretz [possessor of the Land]) only after their immigration into Canaan.

Whether the name of YHWH was known to the patriarchs is doubtful. It is significant that while the epithets Shaddai and El occur frequently in pre-Mosaic and Mosaic-age names, YHWH appears as an element only in the names of Yehoshua' (Joshua) and perhaps of Jochebed--persons who were closely associated with Moses.

The patriarchs are depicted as objects of God's blessing, protection, and providential care. Their response is loyalty and obedience and observance of a cult whose ordinary expression is sacrifice, vow, and prayer at an altar, stone pillar, or sacred tree. Circumcision was a distinctive mark of the cult community.

The eschatology (doctrine of ultimate destiny) of their faith was God's promise of land and a great progeny. Any flagrant contradictions between patriarchal and later mores have presumably been censored; yet distinctive features of the post-Mosaic religion are absent.

The God of the patriarchs shows nothing of YHWH's "jealousy"; no religious tension or contrast with their neighbours appears, and idolatry is scarcely an issue. The patriarchal covenant differed from the Mosaic Sinaitic Covenant in that it was modelled upon a royal grant to favourites and contained no obligations, the fulfillment of which was to be the condition of their happiness. Evidently not the same as the later religion of Israel, patriarchal religion prepared the way for it in its familial basis, its personal call by the deity, and its response of loyalty and obedience to him.

Little can be said of the relation of the religion of the patriarchs to the religions of Canaan. Known points of contact between the two are the divine epithets mentioned above. Like the God of the fathers, El, the head of the Ugaritic pantheon was depicted both as a judgmental and a compassionate deity. Baal (Lord), the aggressive young agricultural deity of Ugarit, is remarkably absent from Genesis. Yet the socioeconomic situation of the patriarchs was so different from the urban, mercantile, and monarchical background of the Ugaritic myths as to render any comparisons highly questionable.

According to Jeremiah (about 100 years later), Micah's prophetic threat to Jerusalem had caused King Hezekiah (reigned c. 715-c. 686 BCE) to placate God--possibly an allusion to the cult reform instituted by the King in order to cleanse Judah from various pagan practices. A heightened concern over assimilatory trends resulted in his also outlawing certain practices considered legitimate up to his time.

Thus, in addition to removing the bronze serpent that had been ascribed to Moses (and that had become a fetish), the reform did away with the local altars and stone pillars, the venerable (patriarchal) antiquity of which did not save them from the taint of imitation of Canaanite practice. Hezekiah's reform, part of a restorational policy that had political, as well as religious, implications, appears as the most significant effect of the fall of the northern kingdom on official religion. The outlook of the reformers is suggested by the catalog in II Kings, chapter 17, of religious offenses that had caused the fall, which the objects of Hezekiah's purge closely resemble. Hezekiah's reform is the first historical evidence for Deuteronomy's doctrine of cult centralization. Similarities between Deuteronomy and the Book of Hosea lend colour to the supposition that the reform movement in Judah, which culminated a century later under King Josiah, was sparked by attitudes inherited from the north.

Hezekiah was the leading figure in a western coalition of states that coordinated a rebellion against the Assyrian king Sennacherib with the Babylonian rebel Merodach-Baladan, shortly after the Assyrian's accession in 705 BCE. When Sennacherib appeared in the west in 701, the rebellion collapsed; Egypt sent a force to aid the rebels, but it was defeated. Hezekiah saw his kingdom overwhelmed and offered tribute to Sennacherib; the Assyrian, however, pressed for the surrender of Jerusalem. In despair, Hezekiah turned to the prophet Isaiah for an oracle. Though the prophet condemned the King's reliance upon Egyptian help, he stood firm in his faith that Jerusalem's destiny precluded its fall into heathen hands. The King held fast, and Sennacherib, for reasons still obscure, suddenly retired from Judah and returned home. This unlooked-for deliverance of the city may have been regarded as a vindication of the prophet's faith and was doubtless an inspiration to the rebels against Babylonia a century later. For the present, while Jerusalem was intact, the country had been devastated and its kingdom turned into a vassal state of Assyria.

During Manasseh's long and peaceful reign in the 7th century BCE, Judah was a submissive ally of Assyria. Manasseh's forces served in the building and military operations of the Assyrian kings Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal. Judah benefitted from the upsurge of commerce that resulted from the political unification of the whole Near East. The prophet Zephaniah attests to heavy foreign influence on the mores of Jerusalem--merchants who adopted foreign dress, cynics who lost faith in the efficacy of YHWH to do anything, people who worshipped the pagan host of heaven on their roofs. Manasseh's court was the centre of such influences.

The royal sanctuary became the home of a congeries of foreign gods--the sun, astral deities, and Asherah (the female fertility deity) all had their cults there alongside YHWH. The countryside also was provided with pagan altars and priests, alongside the local YHWH altars that were revived. Presumably, at least some of the blood that Manasseh is said to have spilled freely in Jerusalem must have belonged to YHWH's devotees. No prophecy is dated to his long reign.

With Ashurbanipal's death in 627, Assyria's power faded quickly; the young Judahite king Josiah (reigned c. 640-609 BCE) had already set in motion a vigorous movement of independence and restoration, a cardinal aspect of which was religious. First came the purge of foreign cults in Jerusalem, under the aegis of the high priest Hilkiah; then the countryside was cleansed. In the course of renovating the Temple, a scroll of Moses' Torah (by scholarly consensus an edition of Deuteronomy) was found. Anxious to abide by its injunctions, Josiah had the local YHWH altars polluted to render them unusable and collected their priests in Jerusalem.

The celebration of the Passover that year was concentrated in the Temple, as it had not been "since the days of the judges who judged Israel," according to II Kings 23:22, or since the days of Samuel, according to II Chron. 35:18; both references reflect the unhistorical theory of the Deuteronomic (Josianic) reformers that the Shiloh sanctuary was the precursor of the Jerusalem Temple as the sole legitimate site of worship in Israel (as demanded by Deuteronomy, chapter 12). To seal the reform, the King convoked a representative assembly and had them enter into a covenant with God over the newfound Torah. For the first time, the power of the state was enlisted on behalf of the ancient covenant and in obedience to a covenant document. It was a major step toward the fixation of a sacred canon.

Josiah envisaged the restoration of Davidic authority over the entire domain of ancient Israel, and the retreat of Assyria facilitated his program--until he became fatally embroiled in the struggle of the powers over the dying empire. His death in 609 was doubtless a setback for his religious policy as well as his political aspirations. To be sure, the royally sponsored syncretism of Manasseh's time was not revived, but there is evidence of recrudescence of unofficial local altars. Whether references in Jeremiah and Ezekiel to child sacrifice to YHWH reflect post-Josianic practices is uncertain. There is stronger indication of private recourse to pagan cults in the worsening political situation.

That Assyria's fall should have been followed by the yoke of a harsh new heathen power dismayed the devotees of YHWH who had not been prepared for it by prophecy. Their mood finds expression in the oracles of the prophet Habakkuk in the last years of the 7th century BCE. Confessing perplexity at God's toleration of the success of the wicked in subjugating the righteous, the prophet affirms his faith in the coming salvation of YHWH, tarry though it might. And in the meantime, "the righteous must live in his faith."

But the situation in fact grew worse as Judah was caught in the Babylonian-Egyptian rivalry. Some attributed the deterioration to the burden of Manasseh's sin that still rested on the people. For the prophet Jeremiah (active c. 626-c. 580 BCE), the Josianic era was only an interlude in Israel's career of guilt that went back to its origins. His pre-reform prophecies denounced Israel as a faithless wife and warned of imminent retribution at the hands of a nameless northerner. After Nebuchadrezzar's decisive defeat of Egypt at Carchemish (605 BCE), Jeremiah identified the scourge as Babylon. King Jehoiakim's attempt to be free of Babylonia ended with the exile of his successor, Jehoiachin, along with Judah's elite (597); yet the court of the new king, Zedekiah, persisted in plotting new revolts, relying--against all experience--on Egyptian support.

Jeremiah now proclaimed a scandalous doctrine of the duty of all nations, Judah included, to submit to the divinely appointed world ruler, the Babylonian monarch Nebuchadrezzar. In submission lay the only hope of avoiding destruction; a term of 70 years had been set to humiliate all men beneath Babylon. Imprisoned for demoralizing the populace, Jeremiah persisted in what was viewed as his traitorous message; the leaders, on their part, persisted in their policy, confident of Egypt and the saving power of Jerusalem's Temple, to the bitter end.

Jeremiah also had a message of comfort for his hearers. He foresaw the restoration of the entire people--north and south--in the land, under a new David. And since events had shown that man was incapable of achieving a lasting reconciliation with God on his own, he envisioned the penitent of the future being met halfway by God, who would remake their nature so that to do his will would come naturally to them. God's new covenant with Israel would be written on their hearts, so that they should no longer need to teach each other obedience, for young and old would know YHWH.

Among the exiles in Babylonia, the prophet Ezekiel, Jeremiah's contemporary, was haunted by the burden of Israel's sin. He saw the defiled Temple of Manasseh's time as present before his eyes, and described God as abandoning it and Jerusalem to their fates. Though Jeremiah offered hope through submission, Ezekiel prophesied an inexorable, total destruction as the condition of reconciliation with God.

The majesty of God was too grossly offended for any lesser satisfaction. The glory of God demanded Israel's ruin, but the same cause required its restoration. For Israel's fall disgraced YHWH among the nations; to save his reputation he must therefore restore Israel to its land.

The dried bones of Israel must revive, that they and all the nations should know that he was YHWH (Ezek. 37). Ezekiel, too, foresaw the remaking of human nature, but as a necessity of God's glorification; the concatenation of Israel's sin, exile, and consequent defamation of God's name must never be repeated. In 587/586 BCE the doom prophecies of Jeremiah and Ezekiel came true. Rebellious Jerusalem was reduced by Nebuchadrezzar, the Temple was burnt, and much of Judah's population dispersed or deported to Babylonia.

The survival of the religious community of exiles in Babylonia demonstrates how rooted and widespread the religion of YHWH was. Abandonment of the national religion as an outcome of the disaster is recorded of a minority only. There were some cries of despair, but the persistence of prophecy among the exiles shows that their religious vitality had not flagged.

The Babylonian Jewish community, in which the cream of Judah lived, had no sanctuary or altar (in contrast to the Jewish garrison of Elephantine in Egypt); what developed in their place can be surmised from new postexilic religious forms: fixed prayer; public fasts and confessions; and assembly for the study of the Torah, which may have developed from visits to the prophets for oracular edification. The absence of a local or territorial focus must also have spurred the formation of a literary-ideational centre of communal life--the sacred canon of Covenant documents that came to be the core of the present Pentateuch.

Observance of the Sabbath--a peculiarly public feature of communal life--achieved a significance among the exiles virtually equivalent to all the rest of the Covenant rules together. Notwithstanding its political impotence, the spirit of the exiles was so high that foreigners were attracted to their ranks, hopeful of sharing their future glory.

Assurance of that future glory was given not only in the consolations promised by Jeremiah and Ezekiel (the fulfillment of whose prophecies of doom lent credit to their consolations); the great comforter of the exile was the writer or writers of what is known as Deutero-Isaiah (Isa. 40-66), who perceived in the rise and progress (from c. 550) of the Persian king Cyrus II the Great the instrument of God's salvation. Going beyond the national hopes of Ezekiel, animated by the universal spirit of the pre-exilic Isaiah, Deutero-Isaiah saw in the miraculous restoration of Israel a means of converting the whole world to faith in Israel's God.

Israel would thus serve as "a light for the nations, that YHWH's salvation may reach to the end of the earth." In his conception of the vicarious suffering of God's servant--through which atonement is made for the ignorant heathen--Deutero-Isaiah found a handle by which to grasp the enigma of faithful Israel's lowly state among the Gentiles. The idea was destined to play a decisive role in the self-understanding of the Jewish martyrs of the Syrian king Antiochus IV Epiphanes' persecution in the 2nd century BCE (in, for example, Daniel) and later again in the Christian appreciation of the death of Jesus.

After conquering Babylon, Cyrus so far justified the hopes put in him that he allowed those Jews who wished to do so to return and rebuild their Temple. Though, in time, some 40,000 made their way back, they were soon disillusioned by the failure of the glories of the restoration to materialize and by the controversy with the Samaritans, and left off building the Temple.

(The Samaritans were a judaized mixture of native north Israelites and Gentile deportees settled by the Assyrians in the erstwhile northern kingdom.) A new religious inspiration came under the governorship of Zerubbabel, a member of the Davidic line, who became the centre of messianic expectations during the anarchy attendant upon the accession to the Persian throne of Darius I (522).

The prophets Haggai and Zechariah perceived the disturbances as heralds of an imminent overthrow of the heathen Persian Empire and a worldwide manifestation of God and glorification of Zerubbabel.

Against that day they urged the people quickly to complete the building of the Temple. The labour was resumed and completed in 516; but the prophecies remained unfulfilled. Zerubbabel disappears from the biblical narrative, and the spirit of the community flagged again.

The one religious constant in the vicissitudes of the restored community was the mood of repentance and the desire to win back God's favour by adherence to his Covenant rules. The anxiety that underlay this mood produced a hostility to strangers, which encouraged a lasting conflict with the Samaritans, who asked permission to take part in rebuilding the Temple of the God they too worshipped.

The Jews, however, rejected them on ill-specified grounds--apparently ethnoreligious; i.e., they felt the Samaritans to be alien to their historical community of faith, especially to its messianic hopes. Nonetheless, intermarriage occurred and precipitated a new crisis when, in 458, the priest Ezra arrived from Babylon, intent on enforcing the regimen of the Torah.

By construing ancient and obsolete laws excluding Canaanites and others so as to make them apply to their own times and neighbors, the leaders of the Jews brought about the divorce and expulsion of several dozen non-Jewish wives and their children. Tension between the xenophobic (fear of strangers) and xenophilic (love of strangers) in postexilic Judaism was finally resolved some two centuries later with the development of a formality of religious conversion, whereby Gentiles who so wished could be taken into the Jewish community by a single, simple procedure.

The decisive constitutional event of the new community was the covenant subscribed to by its leaders in 444, making the Torah the law of the land: a charter granted by the Persian king Artaxerxes I to Ezra--scholar and priest of the Babylonian Exile--empowered him to enforce the Torah as the imperial law for the Jews of the province Avar-nahra (Beyond the River), in which the district of Judah (now reduced to a small area) was located.

The charter required the publication of the Torah and the publication, in turn, entailed its final editing--now plausibly ascribed to Ezra and his circle. Survival in the Torah of patent inconsistencies and disaccords with the postexilic situation indicate that its materials were by then sacrosanct, to be compiled but no longer created. But these survivals made necessary the immediate invention of a harmonizing and creative method of text interpretation to adjust the Torah to the needs of the times.

The Levites were trained in the art of interpreting the text to the people; the first product of the creative exegesis later known as Midrash is to be found in the covenant document of Nehemiah, chapter 9--every item of which shows development, not reproduction, of a ruling of the Torah. Thus, with the publication of the Torah as the law of the Jews the basis of the vast edifice of the Oral Law characteristic of Judaism was laid.

Concern over observance of the Torah was fed by the gap between messianic expectations and the gray reality of the restoration. The gap signified God's continued displeasure, and the only way to regain his favor was to do his will. Thus it is that Malachi, the last of the prophets, concludes with an admonition to be mindful of the Torah of Moses. God's displeasure, however, had always been signalized by a break in communication with him.

As time passed and messianic hopes remained unfulfilled, the sense of a permanent suspension of normal relations with God took hold, and prophecy died out. God, it was believed, would some day be reconciled with his people, and a glorious revival of prophecy would then occur. For the present, however, religious vitality expressed itself in dedication to the development of institutions that would make the Torah effective in life. The course of this development is hidden from view by the dearth of sources from the Persian period. But the community that emerged into the light of history in Hellenistic times is one made over radically by this momentous, quiet process.

Judaism Wikipedia

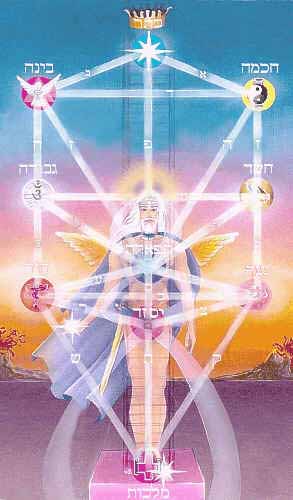

Kabbalah