Josephus, Flavius was a 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian and hagiographer of priestly and royal ancestry who recorded Jewish history, with special emphasis on the 1st century AD and the First Jewish-Roman War, which resulted in the Destruction of Jerusalem and its temple in 70.

His most important works were The Jewish War (c. 75) and Antiquities of the Jews (c. 94). The Jewish War recounts the Jewish revolt against Roman occupation (66-70). Antiquities of the Jews recounts the history of the world from a Jewish perspective for an ostensibly Roman audience. These works provide valuable insight into 1st century Judaism and the background of Early Christianity.

son of Matthias, an ethnic Jew, a priest from Jerusalem" in his first book. He was the second-born son of Matthias and his wife, who was an unnamed Jewish noblewoman. His older brother, his full-blooded sibling, was also called Matthias.

His mother was an aristocratic woman who descended from royalty and of the former ruling Hasmonean Dynasty. JosephusŇ paternal grandparents were Josephus and his wife, an unnamed Jewish noblewoman. His paternal grandparents were distant relatives of each other, as they were both direct descendants of Simon Psellus.

Josephus came from a wealthy, aristocratic family and through his father, he descended from the priestly order of the Jehoiarib, which was the first of the 24 orders of Priests in the Temple in Jerusalem. Through his father, Josephus was a descendant of the High Priest Jonathon. Jonathon may have been Alexander Jannaeus, the High Priest and Hasmonean ruler who governed Judea from 103 BC-76 BC. Born and raised in Jerusalem, Josephus was educated alongside his brother.

He fought the Romans in the First Jewish-Roman War of 66-73 as a Jewish military leader in Galilee. Prior to this, in his early twenties, he traveled to negotiate with Emperor Nero for the release of several Jewish priests. Upon his return to Jerusalem, he was drafted as a commander of the Galilean forces.

After the Jewish garrison of Yodfat fell under siege, the Romans invaded, killing thousands; the survivors committed suicide. According to Josephus, he was trapped in a cave with forty of his companions in July 67. The Romans (commanded by Flavius Vespasian and his son Titus, both subsequently Roman emperors) asked the group to surrender, but they refused. Josephus suggested a method of collective suicide: they drew lots and killed each other, one by one, counting to every third person.

The sole survivor of this process was Josephus (this method as a mathematical problem is referred to as the Josephus problem, or Roman Roulette), who surrendered to the Roman forces and became a prisoner. In 69 Josephus was released. According to his account, he acted as a negotiator with the defenders during the Siege of Jerusalem in 70, in which his parents and first wife died.

It was while being confined at Yodfat that Josephus claimed to have experienced a divine revelation, that later led to his speech predicting Vespasian would become emperor. After the prediction became true he was released by Vespasian who considered his gift of prophecy to be divine. Josephus wrote that his revelation had taught him three things: that God, the creator of the Jewish people, had decided to "punish" them, that "fortune" had been given to the Romans, and that God had chosen him "to announce the things that are to come".

In 71, he went to Rome in the entourage of Titus, becoming a Roman citizen and client of the ruling Flavian dynasty (hence he is often referred to as Flavius Josephus -see below). In addition to Roman citizenship, he was granted accommodation in conquered Judaea, and a decent, if not extravagant, pension. While in Rome and under Flavian patronage, Josephus wrote all of his known works. Although he uses "Josephus", he appears to have taken the Roman praenomen Titus and nomen Flavius from his patrons. This was standard practice for "new" Roman citizens.

Vespasian arranged for the widower Josephus to marry a captured Jewish woman, who ultimately left him. About 71, Josephus married an Alexandrian Jewish woman as his third wife. They had three sons, of whom only Flavius Hyrcanus survived childhood. Josephus later divorced his third wife. Around 75, he married as his fourth wife, a Greek Jewish woman from Crete, who was a member of a distinguished family. They had a happy married life and two sons Flavius Justus and Flavius Simonides Agrippa.

Josephus's life story remains ambiguous. He was described by Harris in 1985 as a law-observant Jew who believed in the compatibility of Judaism and Graeco-Roman thought, commonly referred to as Hellenistic Judaism. Before the nineteenth century, the scholar Nitsa Ben-Ari notes that his work was shunned like that of converts, then banned as those of a traitor, whose work was not to be studied or translated into Hebrew. His critics were never satisfied as to why he failed to commit suicide in Galilee and, after his capture, accepted the patronage of Romans.

The works of Josephus provide crucial information about the First Jewish-Roman War and are also important literary source material for understanding the context of the Dead Sea Scrolls and late Temple Judaism.

Josephan scholarship in the 19th and early 20th century became focused on Josephus' relationship to the sect of the Pharisees. He was consistently portrayed as a member of the sect, and a traitor to the Jewish nation -a view which became known as the classical concept of Josephus. In the mid-20th century, this view was challenged by a new generation of scholars who formulated the modern concept of Josephus. They consider him a Pharisee but restored his reputation in part as patriot and a historian of some standing. Steve Mason in his 1991 book argued that Josephus was not a Pharisee but an orthodox Aristocrat-Priest who became part of the Temple Establishment as a matter of deference, and not willing association.

The works of Josephus include material about individuals, groups, customs and geographical places. Some of these, such as the city of Seron, are not referenced in the surviving texts of any other ancient authority. His writings provide a significant, extra-Biblical account of the post-Exilic period of the Maccabees, the Hasmonean dynasty, and the rise of Herod the Great. He refers to the Sadducees, Jewish High Priests of the time, Pharisees and Essenes, the Herodian Temple, Quirinius' census and the Zealots, and to such figures as Pontius Pilate, Herod the Great, Agrippa I and Agrippa II, John the Baptist, James the brother of Jesus, and a centuries-long disputed reference to Jesus (for more see Josephus on Jesus). He is an important source for studies of immediate post-Temple Judaism and the context of early Christianity.

A careful reading of Josephus' writings and years of excavation allowed Ehud Netzer, an archaeologist from Hebrew University, to discover the location of Herod's Tomb, after a search of 35 years. It was above aqueducts and pools, at a flattened, desert site, halfway up the hill to the Herodium, 12 kilometers south of Jerusalem -as described in Josephus's writings.

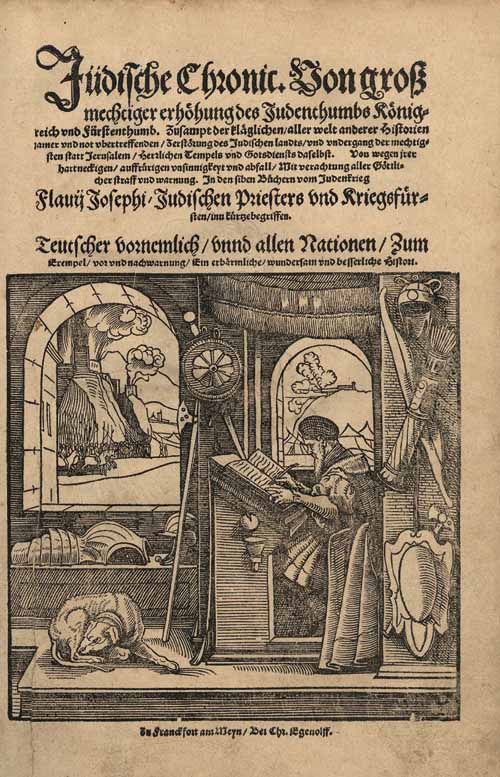

For many years, the works of Josephus were printed only in an imperfect Latin translation from the original Greek. It was only in 1544 that a version of the standard Greek text was made available, edited by the Dutch humanist Arnoldus Arlenius. The first English translation, by Thomas Lodge, appeared in 1602, with subsequent editions appearing throughout the 17th century.

The 1544 Greek edition formed the basis of the 1732 English translation by William Whiston, which achieved enormous popularity in the English-speaking world (and which is currently available online for free download by Project Gutenberg). It was often the book after the Bible that was most frequently owned by Christians. A cross reference apparatus for Whiston's version of Josephus and the biblical canon also exists.

Later editions of the Greek text include that of Benedikt Niese, who made a detailed examination of all the available manuscripts, mainly from France and Spain. This was the version used by H. St J. Thackeray for the Loeb Classical Library edition widely used today. William Whiston, who created perhaps the most famous of the English translations of Josephus, claimed that certain works by Josephus had a similar style to the Epistles of St Paul (Saul).

The standard editio maior of the various Greek manuscripts is that of Benedictus Niese, published 1885-95. The text of Antiquities is damaged in some places. In the Life Niese follows mainly manuscript P, but refers also to AMW and R. Henry St. John Thackery for the Loeb Classical Library has a Greek text also mainly dependent on P. AndrÄ Pelletier edited a new Greek text for his translation of Life. The ongoing Mčnsteraner Josephus-Ausgabe of Mčnster University will provide a new critical apparatus. There also exist late Old Slavonic translations of the Greek, but these contain a large number of Christian interpolations.

(c. 75) War of the Jews, or The Jewish War, or Jewish Wars, or History of the Jewish War (commonly abbreviated JW, BJ or War)

(date unknown) Josephus's Discourse to the Greeks concerning Hades (spurious; adaptation of "Against Plato, on the Cause of the Universe" by Hippolytus of Rome)

(c. 94) Antiquities of the Jews, or Jewish Antiquities, or Antiquities of the Jews/Jewish Archeology (frequently abbreviated AJ, AotJ or Ant. or Antiq.)

(c. 97) Flavius Josephus Against Apion, or Against Apion, or Contra Apionem, or Against the Greeks, on the antiquity of the Jewish people (usually abbreviated CA)

(c. 99) The Life of Flavius Josephus, or Autobiography of Flavius Josephus (abbreviated Life or Vita)

His first work in Rome was an account of the Jewish War, addressed to certain "upper barbarians" - usually thought to be the Jewish community in MesopotamiaĐin his "paternal tongue" (War I.3), arguably the Western Aramaic language. He then wrote a seven-volume account in Greek known to us as the Jewish War (Latin Bellum Judaicum or De Bello Judaico).

It starts with the period of the Maccabees and concludes with accounts of the fall of Jerusalem, and the succeeding fall of the fortresses of Herodion, Macharont and Masada and the Roman victory celebrations in Rome, the mopping-up operations, Roman military operations elsewhere in the Empire and the uprising in Cyrene. Together with the account in his Life of some of the same events, it also provides the reader with an overview of Josephus' own part in the events since his return to Jerusalem from a brief visit to Rome in the early 60s (Life 13-17).

In the wake of the suppression of the Jewish revolt, Josephus would have witnessed the marches of Titus's triumphant legions leading their Jewish captives, and carrying treasures from the despoiled Temple in Jerusalem. He would have experienced the popular presentation of the Jews as a bellicose and xenophobic people.

It was against this background that Josephus wrote his War, and although this work has often been dismissed as pro-Roman propaganda (hardly a surprising view, given the source of his patronage), he claims to be writing to counter anti-Judean accounts. He disputes the claim that the Jews served a defeated God, and were naturally hostile to Roman civilization.

Rather, he blames the Jewish War on what he calls "unrepresentative and over-zealous fanatics" among the Jews, who led the masses away from their traditional aristocratic leaders (like himself), with disastrous results. Josephus also blames some of the Roman governors of Judea, but these he represents as atypical: corrupt and incompetent administrators. Thus, according to Josephus, the traditional Jew was, should be, and can be, a loyal and peace-loving citizen. Jews can, and historically have, accepted Rome's hegemony precisely because their faith declares that God himself gives empires their power.

The next work by Josephus is his twenty-one volume Antiquities of the Jews, completed during the last year of the reign of the Emperor Flavius Domitian (between 1.9.93 and 14.3.94, cf. AJ X.267). In expounding Jewish history, law and custom, he is entering into many philosophical debates current in Rome at that time. Again he offers an apologia for the antiquity and universal significance of the Jewish people.

He outlines Jewish history beginning with the creation, as passed down through Jewish historical tradition. Abraham taught science to the Egyptians, who in turn taught the Greeks. Moses set up a senatorial priestly aristocracy, which, like that of Rome, resisted monarchy. The great figures of the Tanakh are presented as ideal philosopher-leaders. He includes an autobiographical Appendix defending his conduct at the end of the war when he cooperated with the Roman forces.

ANCIENT AND LOST CIVILIZATIONS