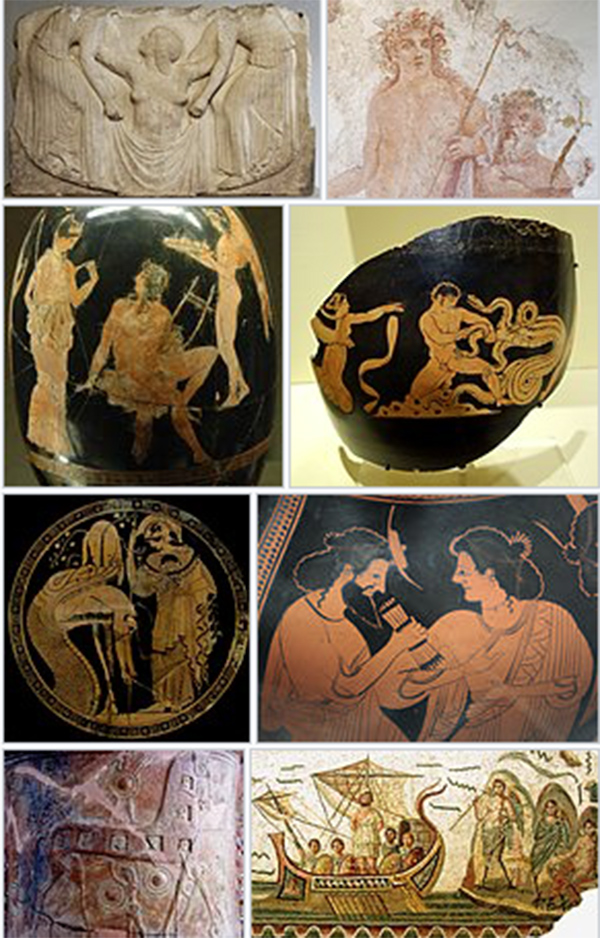

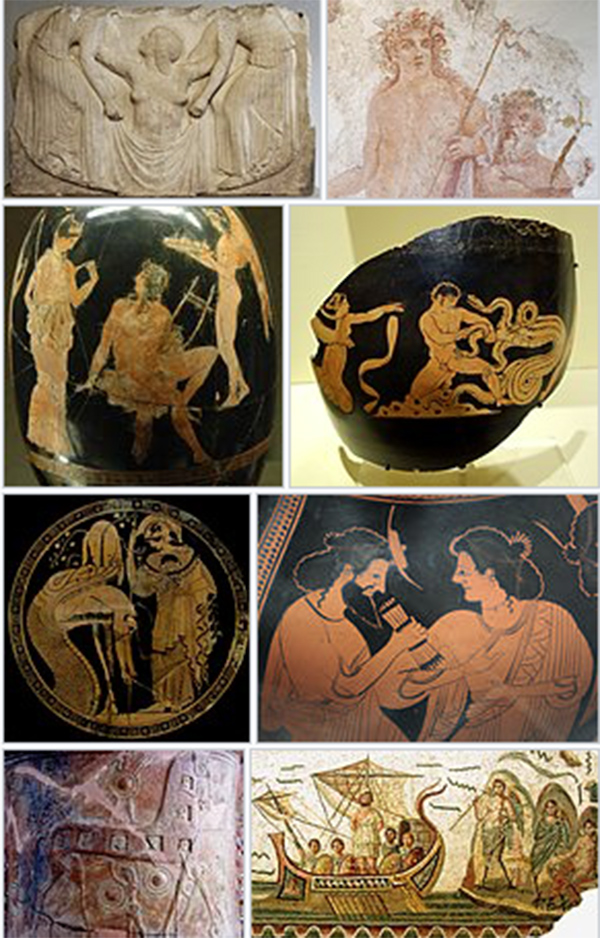

Greek mythology comprises the collected narratives of Greek gods, goddesses, heroes, and heroines, originally created and spread within an oral-poetic tradition. Our surviving sources of mythology are literary reworkings of this oral tradition, supplemented by interpretations of iconic imagery, sometimes modern ones, sometimes ancient ones, as myth was a means for later Greeks themselves to throw light on cult practices and traditions that were no longer explicable. The historian must sometimes deduce from hints in imagery, such as in vase paintings, and offhand references the recognition of mythic themes tacitly expressed in cult practice.

The general issues in studying myths are discussed in the mythography article.In their various legends, stories and hymns the gods of ancient Greece are all described as human in appearance: the few chimerical beings such as the Sphinx all have Near Eastern or Anatolian origins.

The Greek gods may have birth myths but they are unaging. The gods are nearly immune to wounds and to all sickness, capable of becoming invisible, able to travel vast distances almost instantly, and able to speak through human beings with or without their knowledge. Each has his or her own specific appearance, genealogy, interests, personality, and area of expertise; however, these descriptions arise from a multiplicity of archaic local variants, which do not always agree with one another. When these gods were called upon in poetry, prayer or cult, they are referred to by a combination of their name and epithets, that identify them by these distinctions from other manifestations of themselves.

A Greek deity's epithet may reflect a particular aspect of that god's role, as Apollo Musagetes is "Apollo, [as] leader of the Muses." Alternatively the epithet may identify a particular and localized aspect of the god, sometimes thought to be already ancient during the classical epoch of Greece.In such mythic narratives, these beings are described as a large, multi-generational family.

Their oldest members created the world, but succeeding generations overcame the older gods. The Olympian twelve gods most familiar from ancient Greek religion and Greek art are described in epic poems as having appeared in person to the Greeks during the "age of heroes." They provided the struggling ancestors of the Greeks with a limited number of miracles, taught them a selection of useful skills, taught them the methods of worshipping the gods, rewarded virtue and punished vice, and fathered children by humans.

Nature and sources of Greek mythology

While all cultures throughout the world have their own myths, the term mythology is a Greek coinage and had a specialized meaning within Greek culture.

The Greek term muthologia is a compound of two smaller words:

muthos - which in Homeric Greek means roughly "a ritualized speech act", as of a chieftain at an assembly, or of a poet or priest.

logos - which in classical Greek stands for "a convincing story, an ordered argument".

In the original sense, therefore, a mythology is an attempt to bring sense to the stylized narratives that the Greeks recited at festivals, whispered at shrines, and bandied about at aristocratic banquets. Since few breeds of men are more prone to squabbling than poets, priests and aristocrats, contradictions in the material are rife. Moreover, they are part of the fun.

Several types of primary source are available for the study of Greek mythology.

the Homeric Odyssey, Iliad and Hymns

Hesiodic Theogony

Hesiod's Theogony is a large-scale synthesis of a vast variety of local Greek traditions concerning the gods, organized as a narrative that tells how they came to be and how they established permanent control over the cosmos. In many cultures, narratives about the cosmos and about the gods that shaped it are a way for society to reaffirm its native cultural traditions. Specifically, theogonies tend to affirm kingship as the natural embodiment of society. What makes the Theogony of Hesiod unique is that it affirms no historical royal line. Such a gesture would have cited the Theogony in one time and one place. Rather, the Theogony affirms the kingship of the god Zeus himself over all the other gods and over the whole cosmos.

Further, Hesiod appropriates to himself the authority usually reserved to sacred kingship. The poet declares that it is he, where we might have expected some king instead, upon whom the Muses have bestowed the two gifts of a scepter and an authoritative voice (Hesiod, Theogony 30-3), which are the visible signs of kingship. It is not that this gesture is meant to make Hesiod a king. Rather, the point is that the authority of kingship now belongs to the poetic voice, the voice that is declaiming the Theogony.

After the classical period, when divinely-appointed kingship is brought into Greece once more, it will come in from outside, from Macedonia and imported from the royal traditions of Persia.

Although it is often used as a sourcebook for Greek mythology, the Theogony is both more and less than that. In formal terms it is a hymn invoking Zeus and the Muses: parallel passages between it and the much shorter Homeric Hymn to the Muses make it clear that the Theogony developed out of a tradition of hymnic preludes with which ancient Greek rhapsodes would begin their performance at poetic competitions. It is necessary, therefore, to see the Theogony not as a sort of Bible of Greek mythology, but rather as kind of snapshot of a dynamic and often contradictory tradition as it happened to crystalize at one particular place and time - and to remember that the tradition kept evolving all the way up to the time of Nonnus.

the dramatic works of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes

the choral hymns of Pindar and Bacchylides.

2. The work of historians, like Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus, and geographers, like Pausanias and Strabo, who made travels around the Greek world and noted down the stories they heard at various cities.

3. The work of mythographers, who wrote prose treatises based on learned research attempting to reconcile the contradictory tales of the poets. The Bibliotheke by Apollodorus of Athens is the largest extant example of this genre.

4. The poetry of the Hellenistic and Roman ages, which although composed as a literary rather than cultic exercise, nevertheless contains many important details that would otherwise be lost. This category includes the works of:

The Hellenistic poets Apollonius of Rhodes and Callimachus

The Roman poets Hyginus, Ovid, Statius, Valerius Flaccus and Virgil.

The Late Antique Greek poets Nonnus and Quintus Smyrnaeus

5. The ancient novels of Apuleius, Petronius, Lollianus and Heliodorus

An overview

The scope of Greek mythology is enormous. It extends from the horrific crimes of the early gods and the bloody wars of Troy and Thebes, to the childhood pranks of Hermes and the touching grief of Demeter for Persephone. The legions of gods, goddesses, heroes, heroines, monsters, daemons, nymphs, satyrs, and centaurs that one encounters in traversing this vast landscape are beyond count.

Greek mythology has an approximate internal chronology. While contradictions in the material make an absolute timeline impossible, it breaks down roughly into:

2. an age when men and gods mingled freely

3. an age of heroes where divine activity was more limited

While the myths of the age of gods have often been more interesting to contemporary students of myth, Greek authors of the archaic and classical eras had a clear preference for those of the age of heroes: the heroic Iliad and Odyssey, for example, dwarfed the divine-focused Theogony and Homeric Hymns in both size and popularity.

The age of godsLike their neighbors, the Greeks believed in a pantheon of gods and goddesses who were associated with specific aspects of life. For example, Aphrodite was the goddess of sexual desire, while Ares was the god of war and Hades the god of the dead. Some deities like Apollo and Dionysus revealed complex personalities and mixtures of functions, while others like Hestia (literally "hearth") and Helios (literally "sun"), were little more than personifications. There were also site-specific deities, such as river gods and nymphs of springs and caves, and venerated tombs of local heroes and heroines.

Although there were hundreds of beings that could be considered "gods" or "heroes" in one sense or another, some figured only in folklore or were honored locally in particular places (e.g. Trophonius) or at particular festivals (e.g. Adonis). Major sites of ritual, the large temples, were dedicated mostly to a small circle of gods, chiefly the twelve Olympians, Heracles and Asclepius and in some places Helios. These deities were the centers of the large pan-Hellenic cults. Many regions and individual villages had their own cults centered on nymphs, minor deities, heroes or heroines unknown elsewhere; most cities also worshipped the major gods with peculiar local rites and had peculiar local legends about them.

The first gods - To read more about them Click here

One type of narrative about the age of gods tells the story of the birth and conflicts of the first divinities: Chaos, Nyx (Night), Eros (Love), Uranus (the Sky), Gaia (the Earth), the Titans and the triumph of Zeus and the Olympians. Hesiod's Theogony is an example of this type. It was also the subject of many lost poems, including ones attributed to Orpheus, Musaeus, Epimenides, Abaris and other legendary seers, which were used in private ritual purifications and mystery-rites. A few fragments of these works survive in quotations by Neoplatonist philosophers and recently unearthed papyrus scraps.

The earliest Greek thought about poetry considered the theogony, or song about the birth of the gods, to be the prototypical poetic genre - the prototypical muthos - and imputed almost magical powers to it. Orpheus, the archetypal poet, was also the archetypal singer of theogonies, which he uses to calm seas and storms in the Argonautica, and to move the stony hearts of the underworld gods in his descent to Hades. When Hermes invents the lyre in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes, the first thing he does is to sing the birth of the gods. Hesiod's Theogony is not only the fullest surviving account of the gods, but also the fullest surviving account of the archaic poet's function, with its long preliminary invocation to the Muses.

The Age of Gods and Men

Bridging the age when gods lived alone and the age when divine interference in human affairs was limited was a transitional age in which gods and men moved freely together.The most popular type of narrative that confronts gods with early men involves the seduction or rape of a mortal woman by a male god (most often Zeus), resulting in heroic offspring. In a few cases, a female divinity mates with a mortal man, as in the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, where the goddess lies with Anchises to produce Aeneas. The marriage of Peleus and Thetis, which yielded Achilles, is another such myth.

Another type involves the appropriation or invention of some important cultural artifact, as when Prometheus steals fire from the gods, when Tantalus steals nectar and ambrosia from Zeus' table and gives it to his own subjects - revealing to them the secrets of the gods, when Prometheus or Lycaon invents sacrifice, when Demeter teaches agriculture and the Mysteries to Triptolemus, or when Marsyas invents the aulos and enters into a musical contest with Apollo.

Yet another type belongs to Dionysus alone: the god wanders through Greece from foreign lands to spread his cult. He is confronted by a king, Lycurgus or Pentheus, who opposes him, and whom he punishes terribly in return.

The Age of Heroes

The age of heroes can be broken down around the monumental events of the Argonautic expedition and the Trojan War. The Trojan War marks roughly the end of the Heroic Age.

Early Heroes

Among heroes, Heracles is practically in a class by himself. His fantastic solitary exploits, with their many folk tale themes, provided much material for popular legend. His enormous appetite and rustic character also made him a popular figure of comedy, while his pitiful end provided much material for tragedy.

The other members of the earliest generation of heroes, such as Perseus and Bellerophon, have many traits in common with Heracles. Like him, their exploits are solitary, fantastic and border on fairy tale, as they slay monsters like Medusa and the Chimera. This generation was not as popular a subject for poets; we know of them mostly through mythographers and passing remarks in prose writers. They were, however, favorite subjects of visual art.

The Generation of the Argonauts

Nearly every member of the next generation of heroes, as well as Heracles, went with Jason on the expedition to fetch the Golden Fleece. This generation also included Theseus, who went to Crete to slay the Minotaur; Atalanta, the female heroine; and Meleager, who once had an epic cycle of his own to rival the Iliad and Odyssey.

Royal Crimes

In between the Argo and the Trojan War, there was a generation known chiefly for its horrific crimes. This includes the doings of Atreus and Thyestes at Argos; also those of Laius and Oedipus at Thebes, leading to the eventual pillage of that city at the hands of the Seven Against Thebes and Epigoni. For obvious reasons, this generation was extremely popular among the Athenian tragedians.

Troy and Aftermath

As the turning point between the Heroic Age and what the Greek considered the historical period, the Trojan War, its preludes and epilogues, outweighs the rest of the age combined in the sheer amount of source material available. The Trojan cycle includes:

The events leading up to the war: the Judgement of Paris, the abduction of Helen, the sacrifice of Iphigenia at Aulis.

The events of the Iliad, including the quarrel of Achilles with Agamemnon and the deaths of Patroclus and Hector.

The ruse of the Trojan Horse and the destruction of Troy.

The homecomings of heroes from Troy, including the wanderings of Odysseus (the Odyssey) and the murder of Agamemnon

The children of the Trojan generation: e.g. Orestes and Telemachus

Theories of origin

In antiquity, authors like Herodotus speculated that the Greeks had borrowed their gods wholesale from the Egyptians. Later, Christian writers would attempt to explain Hellenic paganism as a degeneration of Biblical religion. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, however, the sciences of archaeology and linguistics were brought to bear on the origins of Greek mythology.

Historical linguistics, on the one hand, shows that certain parts of the Greek pantheon were inherited from Indo-European society, along with the roots of the Greek language. Thus, for example, the name Zeus is cognate with Latin Jupiter, Sanskrit Dyaus and Germanic Tyr (see Dyeus), as is Ouranos with Sanskrit Varuna. In other cases, close parallels in character and function suggest a common heritage, yet lack of linguistic evidence makes it difficult to prove - as in the case of the Greek Moirae and the Norns of Norse mythology.

Archaeology, on the other hand, has shown extensive borrowing by the Greeks from the civilizations of Asia Minor and the Near East. Cybele is a clear example of borrowing from Anatolian culture, while Aphrodite takes much of her iconography and titles from goddesses of the Semitic world such as Ishtar and Astarte.

Textual studies reveal multiple layers in tales, such as secondary asides bringing Theseus into tales of The Twelve Labours of Herakles. Such tales concerning tribal eponyms are thought to originate in attempts to absorb mythology of one tradition into another, in order to unite the cultures.

In addition to Indo-European and Near Eastern origins, some scholars have speculated on the debts of Greek mythology to the still poorly understood pre-Hellenic societies of Greece, such as the Minoans and so-called Pelasgians. This is especially true in the case of chthonic deities and mother goddesses. For some, the three main generations of gods in Hesiod's Theogony (Uranus, Gaia, etc.; the Titans and then the Olympians) suggest a distant echo of a struggle between social groups, mirroring the three major high cultures of Greek civilization: Minoan, Mycenaean and Hellenic.

The extensive parallels between Hesiod's narrative and the Hurrian myth of Anu, Kumarbi, and Teshub makes it very likely that the story is an adaptation of borrowed materials, rather than a distorted historical record. Parallels between the earliest divine generations (Chaos and its children) and Tiamat in the Enuma Elish are possible (Joseph Fontenrose, Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and Its Origins: NY, Biblo-Tannen, 1974).

Jungian scholars such as Karl Kerenyi have preferred to view the origin of myths (and dreams) in universal archetypes. Though not all readers are confident of interpretations of myth in terms of Carl Jung's psychology of dreams (by Kerenyi or Campbell for examples), most agree that myths are dreamlike in two aspects: they are not consistent, perhaps not wholly consistent even within a single myth-element; and they often reflect some momentary experience of the essence of the godhead, some epiphany, which then must be assembled into a narrative thread, much as dreams are recreated as sequential happenings.

In sum, the origins of Greek mythology remain a fascinating and open question.

Did the Greeks believe their myths?

"Our own myths we call reality" is one of the axioms with which Carl A.P. Ruck and Danny Staples commence The World of Classical Myth; to the Greeks, mythology was a part of their history; few ever doubted that there was truth behind the account of the Trojan War in the Iliad and Odyssey. The Greeks used myth to explain natural phenomena, cultural variations, traditional enmities, and friendships. It was a source of pride to be able to trace one's descent from a mythological hero or a god.

Sophisticated Greeks experienced a cultural crisis in the 5th century, when increased literacy and the devopment of logic forced a more comparative skeptical turn of mind, a crisis of which Socrates was the most famous victim.

On the other hand, a few radical philosophers like Xenophanes were already beginning to label the poets' tales as blasphemous lies in the 6th century BC; this line of thought found its most sweeping expression in Plato's Republic and Laws. More sportingly, the 5th century BC tragedian Euripides often played with the old traditions, mocking them, and through the voice of his characters injecting notes of doubt. In other cases Euripides seems to be directing pointed criticism at the behavior of his gods.

Alexandrian poets at first, then more generally literary mythographers in the early Roman Empire, often adapted stories of characters in Greek myth in ways that did not reflect earlier actual beliefs. Many of the most popular versions of these myths that we have today were actually from these fictional retellings, which may blur the archaic beliefs.

Hellenistic Rationalism

The skeptical turn of the Classical age became even more pronounced in the Hellenistic era. Most daringly, the mythographer Euhemerus claimed that stories about the gods were only confused memories of the cruelty of ancient kings. Although Euhemerus's works are lost, interpretations in his style are frequently found in Diodorus Siculus.

Rationalizing hermeneutics of myth became even more popular under the Roman Empire, thanks to the physicalist theories of Stoic and Epicurean philosophy, as well as the pragmatic bent of the Roman mind. The antiquarian Varro, summarizing centuries' worth of philosophic tradition, distinguished three kinds of gods:

The gods of nature: personifications of phenomena like rain and fire.

The gods of the poets: invented by unscrupulous bards to stir the passions.

The gods of the city: invented by wise legislators to soothe and enlighten the populace.

Cicero's De Natura Deorum is the most comprehensive summary of this line of thought.

Syncretizing Trends

One unexpected side-effect of the rationalist view was a popular trend to syncretize multiple Greek and foreign gods in strange, nearly unrecognizable new cults. If Apollo and Serapis and Sabazios and Dionysus and Mithras were all really Helios, why not combine them all together into one Deus Sol Invictus, with conglomerated rites and compound attributes? The surviving 2nd century AD collection of Orphic Hymns and Macrobius's Saturnalia are products of this mind-set.

But though Apollo might in religion be increasingly identified with Helios or even Dionysus, texts retelling his myths seldom reflected such developments. The traditional literary mythology was increasingly dissociated from actual religious practice.

List of Greek Mythological Characters