�Genetics, from the word "Genesis" or "Origin", is the science of genes, heredity, and the variation of organisms. The word "genetics" was first suggested to describe the study of inheritance and the science of variation by the prominent British scientist William Bateson in a personal letter to Adam Sedgwick, dated April 18, 1905. Bateson first used the term "genetics" publicly at the Third International Conference on Genetics (London, England) in 1906.

Heredity and variations form the basis of genetics. Humans applied knowledge of genetics in prehistory with the domestication and breeding of plants and animals. In modern research, genetics provides important tools for the investigation of the function of a particular gene, e.g., analysis of genetic interactions. Within organisms, genetic information generally is carried in chromosomes, where it is represented in the chemical structure of particular DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) molecules. Read more ...

Deoxyribonucleic acid DNA) is a molecule that carries the genetic instructions used in the growth, development, functioning and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses. DNA and RNA are nucleic acids; alongside proteins, lipids and complex carbohydrates (polysaccharides), they are one of the four major types of macromolecules that are essential for all known forms of life. Most DNA molecules consist of two biopolymer strands coiled around each other to form a double helix.

The two DNA strands are termed polynucleotides since they are composed of simpler monomer units called nucleotides. Each nucleotide is composed of one of four nitrogen-containing nucleobases - either cytosine (C), guanine (G), adenine (A), or thymine (T) - and a sugar called deoxyribose and a phosphate group. The nucleotides are joined to one another in a chain by covalent bonds between the sugar of one nucleotide and the phosphate of the next, resulting in an alternating sugar-phosphate backbone. The nitrogenous bases of the two separate polynucleotide strands are bound together (according to base pairing rules (A with T, and C with G) with hydrogen bonds to make double-stranded DNA. The total amount of related DNA base pairs on Earth is estimated at 5.0 x 1037 and weighs 50 billion tonnes. In comparison, the total mass of the biosphere has been estimated to be as much as 4 trillion tons of carbon (TtC).

DNA stores biological information. The DNA backbone is resistant to cleavage, and both strands of the double-stranded structure store the same biological information. This information is replicated as and when the two strands separate. A large part of DNA (more than 98% for humans) is non-coding, meaning that these sections do not serve as patterns for protein sequences.

The two strands of DNA run in opposite directions to each other and are thus antiparallel. Attached to each sugar is one of four types of nucleobases (informally, bases). It is the sequence of these four nucleobases along the backbone that encodes biological information. RNA strands are created using DNA strands as a template in a process called transcription. Under the genetic code, these RNA strands are translated to specify the sequence of amino acids within proteins in a process called translation. Read more

Scientists Successfully Transfer Longevity Gene, Paving the Way for Extending Human Lifespan SciTech Daily - March 6, 2026

Scientists Discover DNA Is Already Organized Before Life Switches On SciTech Daily - February 24, 2026

An early Drosophila embryo captured during a wave of nuclear division. Dividing nuclei (blue) and non-dividing nuclei (pink) illustrate the rapid, highly organized nature of early development and the substantial regulation of genome organization needed to enable proper gene activation despite repeated disruption as nuclei divide.

CRISPR Breakthrough Could Rewrite Future of Genetic Disease Treatment SciTech Daily - December 30, 2025

A new CRISPR approach can control genes without cutting DNA, opening a safer path for treating genetic diseases.

What scientists long believed were knots in DNA may actually be persistent twists formed during nanopore analysis, revealing an overlooked mechanism with major implications. SciTech Daily - December 30, 2025

For decades, researchers interpreted complex electrical patterns seen when DNA moved through nanopores as signs that the molecule was forming knots. Nanopore experiments, which are widely used to study genetic material, seemed to support this idea.

Microscopic Droplets Reveal DNA's Secret Architecture SciTech Daily - December 4, 2025

Inside every human cell, biology manages an extraordinary challenge: packing roughly six feet of DNA into a nucleus that is only about one-tenth the width of a human hair, all while keeping the genetic material fully functional. To achieve this level of compression, DNA coils around proteins to form nucleosomes. These nucleosomes connect like beads on a string, creating long strands that fold into chromatin fibers. The fibers then compact even further to fit inside the nucleus.

Scientists discover first gene proven to directly cause mental illness Science Daily - December 2, 2025

Scientists have discovered that a single gene, GRIN2A, can directly cause mental illness - something previously thought to stem only from many genes acting together. People with certain variants of this gene often develop psychiatric symptoms much earlier than expected, sometimes in childhood instead of adulthood. Even more surprising, some individuals show only mental health symptoms, without the seizures or learning problems usually linked to GRIN2A.

Scientists discover a hidden gene mutation that causes deafness - and a way to fix it Science Daily - October 25, 2025

A newly identified CPD gene mutation causes congenital hearing loss by disrupting arginine metabolism and nitric oxide signaling. Promising treatments using arginine or sildenafil may one day help restore hearing in affected individuals

MIT Scientists Unlock a New Level of Precision in Gene Editing SciTech Daily - October 6, 2025

MIT researchers have developed a more precise form of prime editing, a genome-editing method that corrects faulty genes without making double-stranded DNA cuts. By modifying key proteins, they drastically reduced the error rate, making the technique far safer and more reliable. This breakthrough could accelerate the development of gene therapies for a wide range of diseases.

Researchers have found that nearly three-quarters of the population carry newly identified genetic elements called Inocles, which may influence oral health, immunity, and cancer risk SciTech Daily - September 15, 2025

These structures appear to be essential for helping bacteria adjust to the ever-changing oral environment. The findings shed new light on how bacteria establish themselves and survive in the mouth, with possible consequences for human health, disease, and microbiome research.

Many of these souls were born from 1998 and on where the grids that create the illusion of this reality started to fracture leading to Autism, being on the Autism Spectrum, and other mental health and social issues. Their brains are programmed differently with a connection to technology and AI and a knowing about how broken the simulation is and where it's headed.

The midlife crisis is over, but something worse took its place Science Daily - September 2, 2025

Misery Is Spiking in One Age Group, Overshadowing The Mid-Life Crisis - Gen Z Has Mental Health Issues Science Alert - September 2, 2025

Our genomes are peppered with DNA segments called retrotransposons that can move from place to place. When unleashed, some can kill nerves and promote inflammation - a discovery that may inspire treatments for neuro-degeneration.

Chemists Have Replicated a Critical Moment in The Creation of Life Science Alert - September 2, 2025

The spontaneous coalescence of the molecules that led to life on primordial Earth, some 4 billion years ago, may have finally been observed in a laboratory. Replicating the likely conditions of our newborn planet, chemists have joined together RNA and amino acids – the crucial first step that would eventually lead to the proliferation of living organisms that crawl all over Earth today. The experimental work could yield important clues about the origins of one of the most important biological relationships: the one between nucleic acids and proteins.

DNA has an expiration date. But proteins are revealing secrets about our ancient ancestors we never thought possible. Live Science - August 14, 2025

The moment a creature dies, its DNA begins to break down. Half of it degrades every 521 years on average. By about 6.8 million years, even under ideal preservation conditions in cold, stable environments, every meaningful trace is gone.

Diabetic man produces his own insulin after gene-edited cell transplant Live Science - August 14, 2025

The new proof-of-concept study points a way to curing diabetes without the need for immune-suppressing drugs.

Best-ever map of the human genome sheds light on 'jumping genes,' 'junk DNA' and more Live Science - July 24, 2025

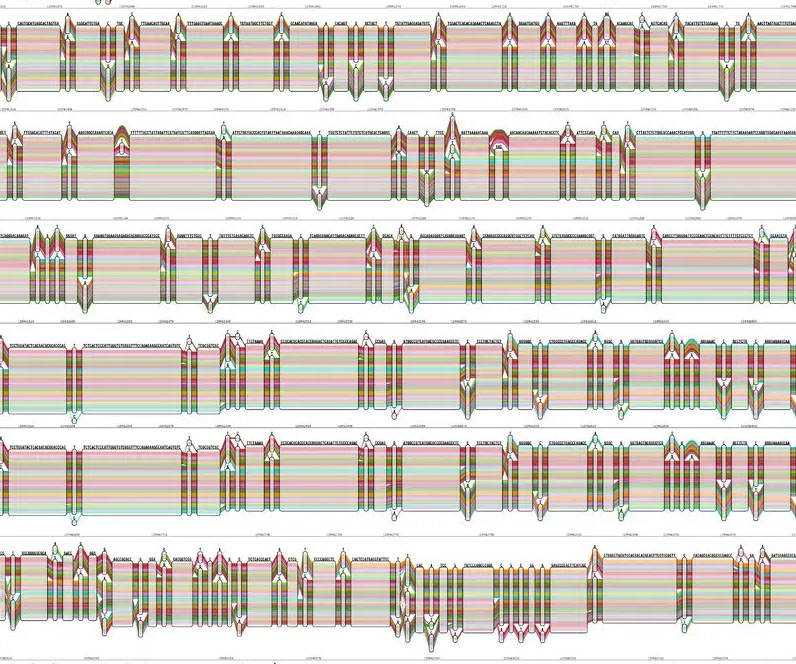

Twenty-two years after the completion of the Human Genome Project, scientists have unveiled the most expansive catalog of human genetic variation ever compiled. Scientists sequenced the DNA of 1,084 people around the world. They leveraged recent technological advancements to analyze long stretches of genetic material from each person, stitched those fragments together and compared the resulting genomes in fine detail. The results deepen our understanding of "structural variants" within the human genome. Rather than affecting a single "letter" in DNA's code, such variations affect large chunks of the code - they may be deleted from or added to the genome, or encompass places where the DNA has been flipped around or moved to a different location.

First Step Towards an Artificial Human Genome Now Underway. Science Alert - July 2, 2025

It's an ambitious and controversial project called the Synthetic Human Genome Project, and work has already begun on a proof-of-concept.

A baby born with a rare and devastating genetic condition has become the first person ever to be successfully treated with a personalized CRISPR therapy Live Science - May 15, 2025

After receiving three doses of the therapy in the past few months, the infant is now 9.5 months old and thriving

Upgraded CRISPR tool enables more seamless gene editing and improved disease modeling PhysOrg - March 20, 2025

Advances in the gene-editing technology known as CRISPR-Cas9 over the past 15 years have yielded important new insights into the roles that specific genes play in many diseases. But to date this technology - which allows scientists to use a "guide" RNA to modify DNA sequences and evaluate the effects - is able to target, delete, replace, or modify only single gene sequences with a single guide RNA and has limited ability to assess multiple genetic changes simultaneously.

Invisible DNA lurks everywhere in the environment and we're on the verge of decoding its secrets Live Science - March 19, 2025

Researchers on Viking's Octantis cruise ship are studying environmental DNA (eDNA) - bits of genetic material that float in the water, drift through the air, or linger in the soil. Every time a living creature passes through an environment, it sheds minuscule bits of its genetic material. Scientists first noticed traces of this genetic material decades ago, but thanks to powerful sequencing techniques, they are now beginning to analyze eDNA to characterize food webs, reveal the locations of long-lost endangered species, and show if predators are lurking in areas where humans and wildlife are in conflict.

Several Psychiatric Disorders Share The Same Root Cause, Study Reveals Science Alert - February 9, 2025

Researchers recently discovered that eight different psychiatric conditions share a common genetic basis. They found many are active for longer during brain development and potentially impact multiple stages, suggesting they could be new targets to treat multiple conditions.

Eight psychiatric disorders share the same genetic causes, study says Medical Express - January 23, 2025

Psychiatric disorders often overlap and can make diagnosis difficult. Depression and anxiety, for example, can coexist and share symptoms. Schizophrenia and anorexia nervosa. Autism and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, too. But, why?

Breakthrough Global Research Finds 293 New Genetic Links to Depression Science Alert - January 17, 2025

Genes play a role in our likelihood of developing depression, and one of the most extensive studies of its kind has now been able to link 293 previously unknown genetic variations to the devastating condition.

'Dark Genes' Hiding Unseen in Human DNA Have Just Been Revealed Science Alert - November 27, 2024

Our records of the human genome may still be missing tens of thousands of 'dark' genes. These hard-to-detect sequences of genetic material can code for tiny proteins, some involved in disease processes like cancer and immunology, a global consortium of researchers has confirmed.

'Dark Genes' Hiding Unseen in Human DNA Have Just Been Revealed Science Alert - November 27, 2024

Scientists have unveiled a new version of the famous gene-editing tool CRISPR, one that can "pause" a given gene temporarily rather than permanently turning it off. The CRISPR revolution started in 2012, when Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier — now Nobel winners — published their discovery of a new gene-editing technique more accurate and efficient than anything tried before. CRISPR has since transformed genetic research and was recently approved for a first-of-its-kind gene therapy for people with blood disorders.

Scientists Discover Rain's Key Role Supporting Early Life on Earth Science Alert - October 18, 2024

Billions of years of evolution have made modern cells incredibly complex. Inside cells are small compartments called organelles that perform specific functions essential for the cell's survival and operation. For instance, the nucleus stores genetic material, and mitochondria produce energy.

Scientists Reconstruct Oldest Human Genomes Ever Found in South Africa Science Alert - September 23, 2024

Researchers have reconstructed the oldest human genomes ever found in South Africa from two people who lived around 10,000 years ago, allowing a better understanding of how the region was populated.

Stunning Crystal Could Preserve The Human Genome For Billions of Years Science Alert - September 23, 2024

50,000 'knots' scattered throughout our DNA control gene activity Live Science - September 3, 2024

Scientists have mapped tens of thousands of mysterious "knots" in human DNA, and they may play a key role in controlling gene activity. Knowing the exact locations of these knots - known as "i-motifs" - could lead to the development of new treatments for diseases, including cancer, according to the researchers behind the work. DNA is composed of building blocks called nucleotides, each of which carries one of the following bases: adenine, guanine, thymine or cytosine. These bases are the individual letters that make up DNA's code. DNA has a ladder-like structure, and normally, bases on one side of the ladder pair with a partner on the other side, linking up in the middle to form the ladder's rungs. Adenine pairs with thymine, while guanine pairs with cytosine.

The Oldest Evidence Of DNA Ever Recovered On Earth was Found in Northern Greenland and is Two Million Years Old IFL Science - July 11, 2024

Unearthed in Ice Age sediment in northern Greenland, the genetic material had been locked in permafrost since the Pliocene. Once sequenced, the DNA opened up a window into the past, shedding light on the array of animals and plants that once inhabited the area. These included reindeer, geese, hares, rodents, crabs, and mastodon, as well as poplar, birch, and thuja trees, and a variety of Arctic and boreal shrubs and herbs.

The Y Chromosome Is Vanishing. A New Sex Gene May Be The Future of Men Science Alert - February 24, 2024

The sex of human and other mammal babies is decided by a male-determining gene on the Y chromosome. But the human Y chromosome is degenerating and may disappear in a few million years, leading to our extinction unless we evolve a new sex gene.

Genomes of 51 animal species mapped in record time, creating 'evolutionary time machine' Live Science - February 3, 2024

These genetic blueprints could have broad implications for humans, particularly for understanding our evolutionary history,

Some chemical tags on DNA, called epigenetic factors, that are present at a young age can affect the maximum life spans of mammal species Science Alert - December 12, 2023

While "genetics" is the study of genes, "epigenetics" is the study of chemical modifications to genes that boost or limit their expression, controlling which genes are switched on or off. These modifications have long been linked to aging, but the new study suggests they also play a role in determining maximum age.

Scientists Reveal a New Way Our DNA Can Make Novel Genes From Scratch Science Alert - December 12, 2023

Scientists have discovered how our DNA can use a genetic fast-forward button to make new genes for quick adaptation to our ever-changing environments. During an investigation into DNA replication errors, researchers from Finland's University of Helsinki found that certain single mutations produce palindromes, which read the same backward and forward. Under the right circumstances, these can evolve into microRNA (miRNA) genes.

Brain cells, interrupted: How some genes may cause autism, epilepsy and schizophrenia - October 2, 2023

A team of researchers has developed a new way to study how genes may cause autism and other neuro-developmental disorders: by growing tiny brain-like structures in the lab and tweaking their DNA. These "assembloids," could one day help researchers develop targeted treatments for autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, schizophrenia, and epilepsy

The Human Y Chromosome Has Just Been Sequenced For The Very First Time IFL Science - August 24, 2023

It’s among the smallest of human chromosomes, but the complex structure of the Y chromosome has made it notoriously resistant to efforts to fully decipher it. Now, the first-ever complete sequence of the Y chromosome has been revealed, bringing us one step closer to solving a plethora of unanswered questions.

Largest-ever genetic family tree reconstructed for Neolithic people in France using ancient DNA Live Science - August 9, 2023

Researchers created two extensive Neolithic family trees using ancient DNA. Using ancient DNA, archaeologists in France have pieced together two elaborate Neolithic family trees that span multiple generations, making them the largest ancestral human record ever reconstructed. The family trees are based on a 6,700-year-old funerary site known as Gurgy, which is located in the Paris Basin region of northern France. Researchers excavated the site in the mid-2000s but, due to advancements in obtaining and analyzing ancient DNA data, recently began studying the genomes of 94 of the 128 individuals, which included children and adults, whose remains were recovered from the site.

The Unknome: Researchers Just Created a Database of Our Most Mysterious Genes Science Alert - August 9, 2023

To increase our understanding of our genetic blueprints researchers have put together a database of genes we know almost nothing about. While we know these genes exist and code for proteins, we have no idea what they're for.

Meet 'Fanzor,' the 1st CRISPR-like system found in complex life Live Science - July 1, 2023

Researchers have identified a new gene-editing system similar to CRISPR in complex organisms, demonstrating for the first time that DNA-modifying proteins exist across all kingdoms of life. The CRISPR-Cas9 system functions as a kind of "molecular scissors" that remove sections of DNA thus disabling genes or allowing new ones to be swapped in.

Newfound CRISPR-Like System In Animals Could Be Used To Manipulate Human Genomes IFL Science - June 30, 2023

A genetic editing system similar to CRISPR-Cas9 has been uncovered for the first time in eukaryotes - the group of organisms that include fungi, plants, and animals. The system, based on a protein called Fanzor, can be guided to precisely target and edit sections of DNA, and that could open up the possibility of its use as a human genome editing tool.

1st draft of a human 'pangenome' published, adding millions of 'building blocks' to the human reference genome Live Science - May 10, 2023

The Pangenome Breakthrough: A Crystal Clear Image of Human Genomic Diversity SciTech Daily - May 13, 2023

In a major advance, scientists have assembled genomic sequences of 47 people from diverse backgrounds to create a pangenome, which offers a more accurate representation of human genetic diversity than the existing reference genome. This new pangenome will help researchers refine their understanding of the link between genes and diseases, and could ultimately help address health disparities.

DNA and Destiny - The Blueprint of your Life/Destiny is encoded in your DNA. There is no Free Will or reality would be very different. Reality is an algorithm set in linear time to experience emotions. There is no Free Will or reality would be very different. Reality is an algorithm set in linear time to experience emotions. Look upon our experiment in humanity as just that - an experiment. We are truth an experiment reaching its conclusion.

Does Your DNA Predict Your Destiny? Are we slaves to our DNA or does our environment have some sway? IFL Science - May 3, 2023

While genes are busy underpinning our physical traits, epigenetics is busy tinkering with our DNA. Epigenetic changes can affect how our bodies 'read' a DNA sequence, effectively turning genes 'on' and 'off' as they please.

25,000-year-old human DNA discovered on Paleolithic pendant from Siberian cave Live Science - May 4, 2023

Artistic interpretation of the Denisova pendant's journey to the ancient DNA extraction. Researchers have retrieved human DNA from a Paleolithic pendant and discovered that it belonged to a Siberian woman who lived roughly 25,000 years ago. This is the first time scientists have successfully isolated DNA from a prehistoric artifact using a newly developed extraction method.

20,000-Year-Old Tooth Pendant In Denisova Cave Belonged To Paleolithic Siberian Woman IFL Science - May 3, 2023

Ancient DNA extracted from a deer tooth pendant has revealed that the age-old jewelry was worn by a single female owner between 19,000 and 25,000 years ago. Found in the famous Denisova Cave in Russia, the trinket belonged to a woman with strong genetic ties to a group of humans that lived further east in Siberia.

Scientists recover an ancient woman's DNA from a 20,000-year-old pendant PhysOrg - May 3, 2023

Artifacts made of stone, bones or teeth provide important insights into the subsistence strategies of early humans, their behavior and culture. However, until now it has been difficult to attribute these artifacts to specific individuals, since burials and grave goods were very rare in the Paleolithic. This has limited the possibilities of drawing conclusions about, for example, division of labor or the social roles of individuals during this period.

DNA methylation markers for increased risk of schizophrenia identified for first time in newborns Medical Express - April 27, 2023

An international research team led by investigators at Virginia Commonwealth University has identified for the first time markers that may indicate early in life if a person has susceptibility to schizophrenia. Although schizophrenia involves an inherited genetic component there is strong evidence that environmental factors play a role in whether a person develops the disease. These environmental factors can trigger chemical changes to DNA that regulate what genes are turned on or off through a process called methylation.

First Fully Complete Human Genome Is Now Available To All IFL Science - April 25, 2023

In 2022, the first fully complete human genome with no gaps was revealed, marking a huge moment for human genetics. On release to the public, scientists described the painstaking work that goes into sequencing an over 6 billion base pair genome, with 200 million added in this new research. The new genome added 99 genes likely to code for proteins and 2,000 candidate genes that were previously unknown. Now, it’s available for all to view.

Unlocking the Secrets of Aging: Researchers Discover Previously Unknown Mechanism That Drives Aging - Gene Length SciTech Daily - January 23, 2023

All cells must balance the activity of long and short genes. The researchers found that longer genes are linked to longer lifespans, and shorter genes are linked to shorter lifespans. They also found that aging genes change their activity according to length. More specifically, aging is accompanied by a shift in activity toward short genes. This causes the gene activity in cells to become unbalanced.

Tiny New Genes Appearing in Human DNA Show How We're Still Evolving Science Alert - December 23, 2022

A new study shows just how human beings continue to evolve in ways we never imagined. New genes typically arise through well known mechanisms like duplication events, where our genetic machinery accidently produces copies of pre-existing genes that can end up suiting new functions over time. But the 155 microgenes pinpointed in this study seem to have appeared from scratch, in stretches of DNA that didn't previously contain the instructions that our bodies use to build molecules. Since the proteins these new genes are thought to encode would be incredibly tiny, these DNA sequences are hard to find and difficult to study, and therefore are often overlooked in research.

Oldest DNA reveals two-million-year-old lost world BBC - December 7, 2022

The most ancient DNA ever sequenced reveals what the Arctic looked like two million years ago when it was warmer. Today the area in North Greenland is a polar desert, but the genetic material, extracted from soil, has uncovered a rich array of plants and animals. The scientists found genetic traces of elephant-like mastodons, reindeer and geese that roamed among birch and poplar trees, and of marine life including horseshoe crabs and algae.

Ancient DNA from medieval Germany tells the origin story of Ashkenazi Jews Science Daily - November 30, 2022

Extracting ancient DNA from teeth, an international group of scientists peered into the lives of a once-thriving medieval Ashkenazi Jewish community in Erfurt, Germany. The findings show that the Erfurt Jewish community was more genetically diverse than modern day Ashkenazi Jews.

Ancient DNA From 1 Million Years Ago Discovered in Antarctica Science Alert - October 10, 2022

As we're a species with ever-shrinking attention spans, it can be difficult to comprehend just how long life has been around on Earth. However, try to get your head around this one: Scientists have dug up fragments of DNA dating back 1 million years ago.

Researchers find 1 million-year-old marine DNA in Antarctic sediment PhysOrg - October 5, 2022

A new study discovered the oldest marine DNA in deep-sea sediments of the Scotia Sea north of the Antarctic continent. The material could be dated to one million years. Such old material demonstrates that sedimentary DNA can open the pathway to study long-term responses of ocean ecosystems to climate change. This recognition will also help with assessing current and future change of marine life around the frozen continent.

Life on Earth began as inserts in an experiment or Simulation that had a beginning and is about to end.

There's Growing Evidence Life on Earth Started With More Than Just RNA Science Alert - July 18, 2022

How life originated on Earth continues to fascinate scientists, but it's not easy peering back billions of years into the past. Now, evidence is growing for a relatively new hypothesis of how life began: with a very precise mix of RNA and DNA.

A Surprising Number of Genetic Mutations Occur Thanks to a Quirk of Quantum Physics Science Alert - May 7, 2022

Mistakes happen. Especially when it comes to the replication of vast sequences of DNA inside our cells. It's a good thing too. If not for the errors in our genes we refer to as mutations, natural selection would be a no-go, and life would be dead in the water.

Quantum mechanics could explain why DNA can spontaneously mutate PhysOrg - May 7, 2022

The molecules of life, DNA, replicate with astounding precision, yet this process is not immune to mistakes and can lead to mutations. Using sophisticated computer modeling, a team of physicists and chemists have shown that such errors in copying can arise due to the strange rules of the quantum world.

Researchers generate the first complete, gapless sequence of a human genome two decades after the Human Genome Project produced the first draft human genome sequence Science Daily - March 31, 2022

Analysis of the complete genome sequence will significantly add to our knowledge of chromosomes, including more accurate maps for five chromosome arms, which opens new lines of research. This helps answer basic biology questions about how chromosomes properly segregate and divide. The T2T consortium used the now-complete genome sequence as a reference to discover more than 2 million additional variants in the human genome. These studies provide more accurate information about the genomic variants within 622 medically relevant genes.

New Evidence Challenges The Idea That Mutations Are Entirely Random Science Alert - January 13, 2022

It's a common misconception that evolution has a sense of direction – a notion that biology nerds around the world are constantly trying to correct. But new research reveals there may be a semblance of truth to this misconception, at least more than we ever realized. While it's not as straightforward as mutation with a purpose, it now appears that not all DNA is equal when it comes to being mutable.

A detailed analysis of scientific research has revealed that nearly 9 in 10 human genes have been mentioned in at least one cancer-related study – and those that haven't probably will be in the years to come Science Alert - November 1, 2021

That makes looking for therapeutic targets very difficult for experts: Research into almost any human gene and its relationship to cancer can be justified based on previous studies, which can slow down the search for genuine genetic causes of the disease, as well as genetic causes involved in other health issues.

Less than 10% of your genome is unique to modern humans, with the rest being shared with ancient human relatives such as Neanderthals, according to a new study Live Science - July 16, 2021

The study researchers also found that the portion of DNA that's unique to modern humans is enriched for genes involved with brain development and brain function. This finding suggests that genes for brain development and function are what really set us apart, genetically, from our ancestors.

New discovery shows human cells can write RNA sequences into DNA Science Daily - June 11, 2021

In a discovery that challenges long-held dogma in biology, researchers show that mammalian cells can convert RNA sequences back into DNA, a feat more common in viruses than eukaryotic cells. Cells contain machinery that duplicates DNA into a new set that goes into a newly formed cell. That same class of machines, called polymerases, also build RNA messages, which are like notes copied from the central DNA repository of recipes, so they can be read more efficiently into proteins. But polymerases were thought to only work in one direction DNA into DNA or RNA. This prevents RNA messages from being rewritten back into the master recipe book of genomic DNA. Now, Thomas Jefferson University researchers provide the first evidence that RNA segments can be written back into DNA, which potentially challenges the central dogma in biology and could have wide implications affecting many fields of biology.

A New Gene Editing Tool Could Rival CRISPR, and Makes Millions of Edits at Once Singularity Hub - May 12, 2021

With CRISPR’s meteoric rise as a gene editing marvel, it’s easy to forget its lowly origins: it was first discovered as a quirk of the bacterial immune system. It seems that bacteria have more to offer. This month, a team led by the famed synthetic biologist Dr. George Church at Harvard University hijacked another strange piece of bacteria biology. The result is a powerful tool that can - in theory - simultaneously edit millions of DNA sequences, with a bar code to keep track of changes. All without breaking a single delicate DNA strand.

Some viruses have a mysterious 'Z' genome. These viruses use a unique genetic alphabet not found anywhere else on the planet Live Science - April 29, 2021

The blueprint for life on our planet is typically written by DNA molecules using a four-letter genetic alphabet. But some bacteria-invading viruses carry around DNA with a different letter - Z - that may help them survive. And new studies show it is much more widespread than previously thought. A series of new papers describe how this strange chemical letter enters into viral DNA, and researchers have now demonstrated that the "Z-genome" is much more widespread in bacteria-invading viruses across the globe - and may have even evolved to help the pathogens survive the hot, harsh conditions of our early planet.

Oldest Modern Human Genome Identified in 45,000-Year-Old Czech Woman Mysterious Universe - April 15, 2021

The oldest modern human genome has been identified in a woman who lived in the Czech Republic about 45,000 years ago. Incredibly, when her remains were found back in 1950, it was believed that she was only about 15,000 years old. What’s even more interesting is that the woman’s genome revealed that her not-so-distant ancestors had relations with Neanderthals.

Researchers can now collect and sequence DNA from the air Live Science - April 8, 2021

We leave DNA all over the place, including in the air, and for the first time, researchers have collected animal DNA from mere air samples, according to a new study. The DNA that living things, human and otherwise, shed into the environment is called environmental DNA (eDNA). Collecting eDNA from water to learn about the species living there has become fairly common, but until now, no one had attempted to collect animal eDNA from the air.

Scientists Have Successfully Sequenced All 64 Human Genomes For First Time Ever News 18 - March 5, 2021

The Human Genome Project began 11 years ago with the ambitious goal to decode the entire human DNA sequencing readable codes. Being one of the biggest achievements of modern science, it encompassed the entirety of the human race and could not be accurate in capturing individual complexities of human genetic variation. But building on the same project, scientists from the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) has successfully sequenced 64 full human genomes. This will help in identifying and cataloguing genetic differences between an individual and the reference genome.

Is the Y chromosome dying out? PhysOrg - August 29, 2020

The sex we're assigned at birth depends largely on a genetic flip of the coin: X or Y? Two X chromosomes and you (almost always) develop ovaries. An X and a Y chromosome? Testes. These packages of genetic material don't just differ in terms of the body parts they give us. With 45 genes (in comparison to around 1,000 on the X), the Y chromosome is puny. And research suggests it has shrunk over time - a proposition that some have, in turns, glumly or gleefully interpreted as predicting the demise of men. So is the Y chromosome really dying out? And what might that mean for men? To begin to answer these questions, we have to go back in time. "Our sex chromosomes weren't always X and Y. What determined maleness or femaleness was not specifically linked to them," said Melissa Wilson, an evolutionary biologist.

DNA from an ancient, unidentified ancestor was passed down to humans living today PhysOrg - August 6, 2020

A new analysis of ancient genomes suggests that different branches of the human family tree interbred multiple times, and that some humans carry DNA from an archaic, unknown ancestor. Roughly 50,000 years ago, a group of humans migrated out of Africa and interbred with Neanderthals in Eurasia. But that's not the only time that our ancient human ancestors and their relatives swapped DNA.

The sequencing of genomes from Neanderthals and a less well-known ancient group, the Denisovans, has yielded many new insights into these interbreeding events and into the movement of ancient human populations. In the new paper, the researchers developed an algorithm for analyzing genomes that can identify segments of DNA that came from other species, even if that gene flow occurred thousands of years ago and came from an unknown source. They used the algorithm to look at genomes from two Neanderthals, a Denisovan and two African humans. The researchers found evidence that 3 percent of the Neanderthal genome came from ancient humans, and estimate that the interbreeding occurred between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago. Furthermore, 1 percent of the Denisovan genome likely came from an unknown and more distant relative, possibly Homo erectus, and about 15% of these "super-archaic" regions may have been passed down to modern humans who are alive today.

The new findings confirm previously reported cases of gene flow between ancient humans and their relatives, and also point to new instances of interbreeding. Given the number of these events, the researchers say that genetic exchange was likely whenever two groups overlapped in time and space. Their new algorithm solves the challenging problem of identifying tiny remnants of gene flow that occurred hundreds of thousands of years ago, when only a handful of ancient genomes are available. This algorithm may also be useful for studying gene flow in other species where interbreeding occurred, such as in wolves and dogs.

Scientists achieve first complete assembly of human X chromosome PhysOrg - July 14, 2020

Although the current human reference genome is the most accurate and complete vertebrate genome ever produced, there are still gaps in the DNA sequence, even after two decades of improvements. Now, for the first time, scientists have determined the complete sequence of a human chromosome from one end to the other ('telomere to telomere') with no gaps and an unprecedented level of accuracy.

For The First Time, Scientists Have Completely Sequenced a Human Chromosome Science Alert - July 14, 2020

In 2003, history was made. For the first time, the human genome was sequenced. Since then, technological improvements have enabled tweaks, adjustments, and additions, making the human genome the most accurate and complete vertebrate genome ever sequenced. Nevertheless, some gaps remain - including human chromosomes. We have a pretty good grasp of them in general, but there are still some gaps in the sequences. Now, for the first time, geneticists have closed some of those gaps, giving us the first complete, gap-free, end-to-end (or telomere-to-telomere) sequence of a human X chromosome.

Genes from 'culturally extinct' Indigenous group discovered in unsuspecting Tennessee man Live Science - July 2, 2020

The last known members of the Indigenous Beothuk people of Newfoundland were thought to have died out 200 years ago. But genes from these people have been found in a man living in Tennessee today, researchers reported. Shanawdithit, a Beothuk woman who died of tuberculosis in 1829, was the last known Beothuk. The group had thrived in Newfoundland with as many as 2,000 people there, until the Europeans arrived in the early 1500s, bringing disease and pushing the Beothuk inland, away from their traditional fishing and hunting grounds, which led to their starvation.

This bizarre virus has genes never seen before in any life-form Live Science - February 11, 2020

This bizarre virus has genes never seen before in any life-form.

Our planet is teeming with mysterious microbes. Now, in the waters of an artificial lake, scientists may have discovered one of the most mysterious of all: a brand-new virus with genes that have never been seen before. A couple of years ago, the group collected water samples from the creeks of Lake Pampulha, an artificial lagoon in the city of Belo Horizonte in Brazil, in search of giant viruses - or those with massive genomes - that infect single-celled organisms called amoebas. But when the team went back to the lab and added these samples to amoeba cells to try to catch giant viruses in their attempt to infect the cells, they found a much smaller intruder.

DNA from Stone Age woman obtained 6,000 years on BBC - December 17, 2019

Thanks to the tooth marks she left in ancient "chewing gum", scientists were able to obtain DNA, which they used to decipher her genetic code. This is the first time an entire ancient human genome has been extracted from anything other than human bone, said the researchers.

She likely had dark skin, dark brown hair and blue eyes. The "chewing gum" - actually tar from a tree - is a very valuable source of ancient DNA, especially for time periods where we have no human remains.

Gene identified critical to clearing up unnecessary proteins that play a role in brain development and contributes to the development of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and schizophrenia Medical Express - November 25, 2019

Researchers have identified that a gene critical to clearing up unnecessary proteins plays a role in brain development and contributes to the development of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and schizophrenia.

Genetic regions associated with left-handedness identified and linked with brain architecture in language regions Science Daily - September 7, 2019

A new study has for the first time identified regions of the genome associated with left-handedness in the general population and linked their effects with brain architecture. Of the four genetic regions they identified, three of these were associated with proteins involved in brain development and structure. In particular, these proteins were related to microtubules, which are part of the scaffolding inside cells, called the cytoskeleton, which guides the construction and functioning of the cells in the body.

Danger avoidance can be genetically encoded for four generations, say biologists Science Daily - June 6, 2019

Researchers have discovered that learned behaviors can be inherited for multiple generations in C. elegans, transmitted from parent to progeny via eggs and sperm cells.

Oldest Scandinavian human DNA found in ancient chewing gum PhysOrg - May 15, 2019

The first humans who settled in Scandinavia more than 10,000 years ago left their DNA behind in ancient chewing gum, masticated lumps made from birch bark pitch.

This Man's DNA Is the Oldest in North America Live Science - May 8, 2019

A Native American man in Montana has what may be the oldest DNA native to the Americas, according to news reports. After getting his DNA tested, Darrell "Dusty" Crawford learned that his ancestors were already in the Americas about 17,000 years ago, according to the Great Falls Tribune, a Montana newspaper. The company Cellular Research Institute (CRI) Genetics traced Crawford's ancestry back 55 generations with 99% accuracy, a rare feat given how convoluted family trees can be. The test also revealed the origins of his Blackfeet ancestors. According to his DNA, Crawford's ancestors are from the Pacific Islands. Then, they journeyed to the South American coast and traveled north, according to a preliminary analysis. Moreover, CRI Genetics looked at Crawford's mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), genetic material that is passed down through mothers. An analysis showed that Crawford is part of the mtDNA haplotype B2 group, which originated in Arizona about 17,000 years ago, the Great Falls Tribune reported.

Study reveals genes associated with heavy drinking and alcoholism Medical Express - April 2, 2019

A large genomic study of nearly 275,000 people led by Penn Medicine researchers revealed new insights into genetic drivers of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder (AUD), the uncontrollable pattern of alcohol use commonly referred to as alcoholism. In the largest-ever genome-wide association study (GWAS) of both traits in the same population, a team of researchers found 18 genetic variants of significance associated with either heavy alcohol consumption, AUD, or both. Interestingly, while five of the variants overlapped, eight were only associated with consumption and five with AUD only.

A fail-safe mechanism for DNA repair PhysOrg - March 25, 2019

Single-molecule fluorescent measurements provide fresh insights into a process for keeping errors out of our genomes.

Study uncovers genetic switches that control process of whole-body regeneration Science Daily - March 15, 2019

Researchers are shedding new light on how animals perform whole-body regeneration, and uncovered a number of DNA switches that appear to control genes used in the process.

Study sheds more light on genes' 'on/off' switches Medical Express - February 26, 2019

It takes just 2 percent of the human genome to code for all of the proteins that make cellular functions - from producing energy to repairing tissues possible. So what does the other 98 percent do?

Family tree of 400 million people shows genetics has limited influence on longevity Science Daily - November 6, 2018

Although long life tends to run in families, genetics has far less influence on life span than previously thought, according to a new analysis of more than 400 million people. The results suggest that the heritability of life span is well below past estimates, which failed to account for our tendency to select partners with similar traits to our own.

A mission to sequence the genome of every known animal, plant, fungus and protozoan - a group of single-celled organisms - is underway BBC - November 1, 2018

The Earth BioGenome Project (EBP) has been described as a "moonshot for biology". A key aim is to use the information in efforts to conserve threatened species. Scientists say clues about how species adapt to environmental change could be hidden in their DNA code.

World's longest DNA sequence decoded BBC - October 31, 2018

The scientists produced a DNA read that is about 10,000 times longer than normal, and twice as large as a previous record holder, from Australia. This research has kick-started an Ashes-style competition to sequence an entire chromosome in a single read. The new holder of the trophy for world's longest DNA read is a team led by Matt Loose at Nottingham University. The advance is a technological one - this is about reading the DNA rather than the discovery of a particularly large genome. The DNA used for the long read came from a human.

But the scientists hope the work will make it quicker and easier to sequence genetic information because, currently, DNA has to be chopped up into smaller pieces and then reassembled during the process of sequencing. Dr Loose's group also recently produced the most complete human genome sequence using a palm-sized "nanopore" sequencing machine. These potentially offer lower cost and faster processing for DNA sequencing.

Genetic disease healed using genome editing Medical Express - October 8, 2018

Enhancement of the CRISPR/Cas9 system

Scientists reverse a sensory impairment in mice with autism Medical Express - September 25, 2018

Using a genetic technique that allows certain neurons in the brain to be switched on or off, UCLA scientists reversed a sensory impairment in mice with symptoms of autism, enabling them to learn a sensory task as quickly as healthy mice.

Thousands of unknown DNA changes in the developing brain revealed by machine learning Medical Express - September 24, 2018

Unlike most cells in the rest of our body, the DNA (the genome) in each of our brain cells is not the same: it varies from cell to cell, caused by somatic changes. This could explain many mysteries - from the cause of Alzheimer's disease and autism to how our personality develops. But much remains unknown, including when these changes arise, their size and locations, and whether they are random or regulated. DNA technologies used to study these "copy number variations" (CNVs) in single brain cells have been limited to longer DNA sequences - those above one million base pairs.

Researchers outline game-theory approach to better understand genetics PhysOrg - September 5, 2018

Principles of game theory offer new ways of understanding genetic behavior, a pair of researchers has concluded in a new analysis. The exploration considers signaling game theory, which involves sender and receiver interactions with both seeking payoffs.

Genes that regulate how much we dream Medical Express - August 28, 2018

Sleep is known to re-energize animals and consolidate their memories. Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, a mysterious stage of sleep in which animals dream, is known to play an important role in maintaining a healthy mental and physical life, but the molecular mechanisms behind this state are poorly understood. Now, an international research team led by researchers at the RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research (BDR) in Japan has identified a pair of genes that regulate how much REM and non-REM sleep an animal experiences.

Gene-editing technique cures genetic disorder in utero Science Daily - July 9, 2018

Researchers have for the first time used a gene editing technique to successfully cure a genetic condition in a mouse model. Their findings present a promising new avenue for research into treating genetic conditions during fetal development.

Jumping genes: Cross species transfer of genes has driven evolution Science Daily - July 9, 2018

Far from just being the product of our parents, scientists have now shown that widespread transfer of genes between species has radically changed the genomes of today's mammals, and been an important driver of evolution.

New CRISPR technology 'knocks out' yeast genes with single-point precision PhysOrg - May 7, 2018

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has given researchers the power to precisely edit selected genes. Such genome-scale engineering - in contrast to traditional strategies that only target a single gene or a limited number of genes - allows researchers to study the role of each gene individually, as well as in combination with other genes. It also could be useful for industry, where S. cerevisiae is widely used to produce ethanol, industrial chemicals, lubricants, pharmaceuticals and more.

Stomata - the plant pores that give us life -arise thanks to a gene called MUTE, scientists report PhysOrg - May 7, 2018

Through photosynthesis, they use sunlight and carbon dioxide to make food, belching out the oxygen that we breathe as a byproduct. This evolutionary innovation is so central to plant identity that nearly all land plants use the same pores - called stomata -to take in carbon dioxide and release oxygen. Stomata are tiny, microscopic and critical for photosynthesis. Thousands of them dot on the surface of the plants. Understanding how stomata form is critical basic information toward understanding how plants grow and produce the biomass upon which we thrive.

Forty-four genomic variants linked to major depression Science Daily - April 26, 2018

A new meta-analysis of more than 135,000 people with major depression and more than 344,000 controls has identified 44 genomic variants, or loci, that have a statistically significant association with depression.

Found: A new form of DNA in our cells Science Daily - April 23, 2018

In a world first, researchers have identified a new DNA structure -- called the i-motif -- inside cells. A twisted 'knot' of DNA, the i-motif has never before been directly seen inside living cells. Deep inside the cells in our body lies our DNA. The information in the DNA code -- all 6 billion A, C, G and T letters -- provides precise instructions for how our bodies are built, and how they work. The iconic 'double helix' shape of DNA has captured the public imagination since 1953, when James Watson and Francis Crick famously uncovered the structure of DNA. However, it's now known that short stretches of DNA can exist in other shapes, in the laboratory at least -- and scientists suspect that these different shapes might play an important role in how and when the DNA code is 'read'.

How ancient DNA is transforming our view of the past BBC - April 11, 2018

If it seems as if there has been an avalanche of recent headlines revealing insights into the travails of our ancient ancestors, you'd be right.

From the fate of the people who built Stonehenge to the surprising physical appearance of Cheddar Man, a 10,000-year-old Briton, the deluge of information has been overwhelming. But this step change in the understanding of our past has been building for years now. It's been driven by new techniques and technological advancements in the study of ancient DNA - genetic information retrieved from the skeletal remains of our long-dead kin.

People in West Africa still carry 'beneficial' genes from a mystery ancient human ancestor that protects them against tumors Daily Mail - April 3, 2018

Evidence of an unknown species of human ancestor has been found hiding in the DNA of West African people. Experts made the finding by analyzing the human genome, looking for strings of genetic information that were out of place. This revealed an inheritance of markers from an unidentified human-like species, some of which may be of benefit to their descendants - including one which suppresses the development of tumors. Researchers believe an ancient species of hominin, known as Homo heidelbergensis, may be the most likely candidate for the 'ghost' species.

DNA reveals thousands of years of social inequality: Expert reveals how the spread of powerful men throughout history is linked to genetics Daily Mail - April 2, 2018

Prof. Reich argues in the piece that men have been more able to assert power historically because of their genes.

Research signals arrival of a complete human genome PhysOrg - March 19, 2018

It's been nearly two decades since a UC Santa Cruz research team announced that they had assembled and posted the first human genome sequence on the internet. Despite the passage of time, enormous gaps remain in our genomic reference map. These gaps span each human centromere. New research from a UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute is attempting to close these gaps. The research uses nanopore long-read sequencing to generate the first complete and accurate linear map of a human Y chromosome centromere. This milestone in human genetics and genomics signals that scientists are finally entering a technological phase when completing the human genome will be a reality.

Researchers measure gene activity in single cells PhysOrg - March 17, 2018

For biologists, a single cell is a world of its own: It can form a harmonious part of a tissue, or go rogue and take on a diseased state, like cancer. But biologists have long struggled to identify and track the many different types of cells hiding within tissues. Researchers at the have developed a new method to classify and track the multitude of cells in a tissue sample. The team reports that this new approach known as SPLiT-seq - reliably tracks gene activity in a tissue down to the level of single cells.

'Dark Matter' DNA Influences Brain Development Scientific American - January 22, 2018

Researchers are finally figuring out the purpose behind some genome sequences that are nearly identical across vertebrates. A puzzle posed by segments of 'dark matter' in genomes - long, winding strands of DNA with no obvious functions - has teased scientists for more than a decade. Now, a team has finally solved the riddle. The conundrum has centered on DNA sequences that do not encode proteins, and yet remain identical across a broad range of animals. By deleting some of these ‘ultraconserved elements’, researchers have found that these sequences guide brain development by fine-tuning the expression of protein-coding genes.

Gene Location for Paranoia Found Live Science - January 17, 2018

Our genes shape the way we look and how our bodies work, and looking at specific genes or snippets of DNA can offer scientists a glimpse of the control panels for many different physical traits. But researchers are still piecing together the relationship between genes and behavior, and indeed, little is known about how certain types of genes can influence human psychology. Recently, a rare disorder known as Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) gave scientists an unprecedented opportunity to pinpoint the location of certain genetic activity associated with paranoia, a mental condition that frequently occurs in people with PWS. Many traits found in people with PWS — including paranoia — are associated with anomalies in two genes on a single chromosome. In a new study, scientists investigated the genetic makeup of people with the syndrome, noting which individuals exhibited more signs of paranoid behavior and looking for patterns in gene expression, which is the activation of information coded in a gene, to shape a particular trait.

Human immunity can kill the CRISPR gene therapy - but the technology is far from dead, expert says Daily Mail - January 8, 2018

The gene-editing technology some thought would change the nature of medicine may not be able to withstand the attacks of the human immune system, a new study suggests. The biotechnology, called CRISPR-Cas9, has been hailed as one of the greatest scientific developments of the last decade for its promising ability to edit or fix genetic mutations to treat - and perhaps some day prevent - diseases. Researchers at Stanford University sought to find out if the human body would reject cells after they had been edited using Cas9, an enzyme derived from bacteria, and reintroduced to the body. In the experiment, the human body recognized and destroyed the bacterial cells, but the scientists say we shouldn't write the technology off so quickly.

Researchers find genes may 'snowball' obesity Medical Express - December 7, 2017

There are nine genes that make you gain more weight if you already have a high body mass index. The effect of these genes may be amplified by four times, if we compare the 10% of the population at the low end of the body mass index, compared to the 10% at the high end. Although the increasing average body mass index of the population of several high-income countries has recently plateaued, the researchers note in the study, the cases of extreme forms of obesity are still growing. People who are morbidly obese are at risk of health complications such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and cancers and early death.

CRISPR-Cas9 technique targeting epigenetics reverses disease in mice Science Daily - December 7, 2017

Scientists report a modified CRISPR-Cas9 technique that alters the activity, rather than the underlying sequence, of disease-associated genes. The researchers demonstrate that this technique can be used in mice to treat several different diseases. Much of the enthusiasm around gene-editing techniques, particularly the CRISPR-Cas9 technology, centers on the ability to insert or remove genes or to repair disease-causing mutations. A major concern of the CRISPR-Cas9 approach, in which the double-stranded DNA molecule is cut, is how the cell responds to that cut and how it is repaired. With some frequency, this technique leaves new mutations in its wake with uncertain side effects.

Number of genetic markers linked to lifespan triples - 25 genetic variants linked to human longevity Science Daily - December 7, 2017

Researchers have studied 389,166 volunteers who gave DNA samples to the UK Biobank, US Health and Retirement Study and the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. In addition to confirming the eight genetic variants that had already been linked to longevity, this study found 17 more to expand the list of known variants affecting lifespan to 25 genes, with some sex-specific.

Precise DNA editing made easy: New enzyme to rewrite the genome Science Daily - October 26, 2017

A new type of DNA editing enzyme lets scientists directly and permanently change single base pairs of DNA from A*T to G*C. The process could one day enable precise DNA surgery to correct mutations that cause human diseases. The newly created DNA base editor contains an atom-rearranging enzyme (red) that can change adenine into inosine (read and copied as guanine), guide RNA (green) which directs the molecule to the right spot, and Cas9 nickase (blue), which snips the opposing strand of DNA and tricks the cell into swapping the complementary base.

Genes responsible for diversity of human skin colors identified Science Daily - October 12, 2017

A study of diverse African groups by geneticists has identified new genetic variants associated with skin pigmentation. The findings help explain the vast range of skin color on the African continent, shed light on human evolution and inform an understanding of the genetic risk factors for conditions such as skin cancer.

DNA surgery on embryos removes disease BBC - September 29, 2017

Precise "chemical surgery" has been performed on human embryos to remove disease in a world first, Chinese researchers have told the BBC. The team used a technique called base editing to correct a single error out of the three billion "letters" of our genetic code. They altered lab-made embryos to remove the disease beta-thalassemia. The embryos were not implanted. The team says the approach may one day treat a range of inherited diseases. Base editing alters the fundamental building blocks of DNA: the four bases adenine, cytosine, guanine and thymine. They are commonly known by their respective letters, A, C, G and T. All the instructions for building and running the human body are encoded in combinations of those four bases.

Introducing ‘dark DNA' – the phenomenon that could change how we think about evolution The Conversation - September 14, 2017

But in some cases we're faced with a mystery. Some animal genomes seem to be missing certain genes, ones that appear in other similar species and must be present to keep the animals alive. These apparently missing genes have been dubbed 'dark DNA'. And its existence could change the way we think about evolution.

Sixteen genetic markers can cut a life story short Science Daily - July 28, 2017

The answer to how long each of us will live is partly encoded in our genome. Researchers have identified 16 genetic markers associated with a decreased lifespan, including 14 new to science. This is the largest set of markers of lifespan uncovered to date. About 10% of the population carries some configurations of these markers that shorten their life by over a year compared with the population average. This study provides a powerful computational framework to uncover the genetics of our time of death, and ultimately of any disease.

10 Amazing Things Scientists Just Did with CRISPR Live Science - June 26, 2017

It's like someone has pressed fast-forward on the gene-editing field: A simple tool that scientists can wield to snip and edit DNA is speeding the pace of advancements that could lead to treating and preventing diseases.

CRISPR Editing of Human Embryos Brings Us Closer to GMO Babies Seeker - July 28, 2017

A new development in CRISPR technology ignites ethics debates about how much control we should have over our own genome. The first human embryos in the United States have been edited by the CRISPR-Cas9 system, according to an exclusive report by the MIT Technology Review. The results of the research haven't been published yet, so it's hard to establish exactly what happened. But if true, the research could herald a new era in human gene editing and experimentation.

Psychics do it all the time

Genes influence ability to read a person's mind from their eyes Science Daily - June 7, 2017

Our DNA influences our ability to read a person's thoughts and emotions from looking at their eyes, suggests a new study published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry. Twenty years ago, a team of scientists at the University of Cambridge developed a test of 'cognitive empathy' called the 'Reading the Mind in the Eyes' Test (or the Eyes Test, for short). This revealed that people can rapidly interpret what another person is thinking or feeling from looking at their eyes alone. It also showed that some of us are better at this than others, and that women on average score better on this test than men.

Now, the same team, working with the genetics company 23andMe along with scientists from France, Australia and the Netherlands, report results from a new study of performance on this test in 89,000 people across the world. The majority of these were 23andMe customers who consented to participate in research. The results confirmed that women on average do indeed score better on this test. More importantly, the team confirmed that our genes influence performance on the Eyes Test, and went further to identify genetic variants on chromosome 3 in women that are associated with their ability to "read the mind in the eyes."

First-ever look at DNA opening reveals initial stage of reading the genetic code PhysOrg - June 2, 2017

Scientists have watched a cell's genetic machinery in the first stages of 'reading' genes, giving a potential way to stop the process in bacteria. By reading certain genes - a process known as transcription - cells can produce and regulate proteins, which perform almost all the functions necessary for life.

DNA of extinct humans found in caves BBC - April 28, 2017

The DNA of extinct humans can be retrieved from sediments in caves - even in the absence of skeletal remains. Researchers found the genetic material in sediment samples collected from seven archaeological sites. The remains of ancient humans are often scarce, so the new findings could help scientists learn the identity of inhabitants at sites where only artifacts have been found. Researchers were able to identify the DNA of various animals belonging to 12 mammalian families, including extinct species such as the woolly mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, cave bear and cave hyena.

We Could Back Up The Entire Internet On A Gram Of DNA Seeker - March 16, 2017

Nature's code for life is stored in DNA, but what if we could code anything we wanted into DNA? Scientists are figuring out how.

Visualizing the genome: First 3-D structures of active DNA created Science Daily - March 13, 2017

Scientists have determined the first 3-D structures of intact mammalian genomes from individual cells, showing how the DNA from all the chromosomes intricately folds to fit together inside the cell nuclei. Most people are familiar with the well-known 'X' shape of chromosomes, but in fact chromosomes only take on this shape when the cell divides. Using their new approach, the researchers have now been able to determine the structures of active chromosomes inside the cell, and how they interact with each other to form an intact genome. This is important because knowledge of the way DNA folds inside the cell allows scientists to study how specific genes, and the DNA regions that control them, interact with each other. The genome's structure controls when and how strongly genes -- particular regions of the DNA -- are switched 'on' or 'off'. This plays a critical role in the development of organisms and also, when it goes awry, in disease.

Gene found to cause sudden death in young people Science Daily - March 9, 2017

A new gene that can lead to sudden death among young people and athletes has now been identified by an international team of researchers. The gene, called CDH2, causes arrhythmogenic right ventricle cardiomyopathy (ARVC), which is a genetic disorder that predisposes patients to cardiac arrest and is a major cause of unexpected death in seemingly healthy young people.

With stringent oversight, heritable human genome editing could be allowed Science Daily - February 14, 2017

Clinical trials for genome editing of the human germline -- adding, removing, or replacing DNA base pairs in gametes or early embryos -- could be permitted in the future, but only for serious conditions under stringent oversight, says a new report. Genome editing is not new. But new powerful, precise, and less costly genome editing tools, such as CRISPR/Cas9, have led to an explosion of new research opportunities and potential clinical applications, both heritable and non-heritable, to address a wide range of human health issues. Recognizing the promise and the concerns related to this technology, NAS and NAM appointed a study committee of international experts to examine the scientific, ethical, and governance issues surrounding human genome editing.

Genomes in flux: New study reveals hidden dynamics of bird and mammal DNA evolution PhysOrg - February 6, 2017

Evolution is often thought of as a gradual remodeling of the genome, the genetic blueprints for building an organism. But in some instance it might be more appropriate to call it an overhaul. Over the past 100 million years, the human lineage has lost one-fifth of its DNA, while an even greater amount was added. Until now, the extent to which our genome has expanded and contracted had been under-appreciated, masked by its relatively constant size over evolutionary time. Humans aren't the only ones with elastic genomes. A new look at a virtual zoo-full of animals, from hummingbirds to bats to elephants, suggests that most vertebrate genomes have the same accordion-like properties.

Hijacking the double helix for replication PhysOrg - December 13, 2016

For years, scientists have puzzled over what prompts the intertwined double-helix DNA to open its two strands and then start replication. Knowing this could be the key to understanding how organisms - from healthy cells to cancerous tumors - replicate and multiply for their survival. A group of USC scientists believe they have solved the mystery. Replication is prompted by a ring of proteins that bond with the DNA at a special location known as "origin DNA." The ring tightens around the strands and melts them to open up the DNA, initiating replication.

Twelve DNA areas linked with the age at which we have our first child and family size Medical Express - October 31, 2016

Researchers have identified 12 specific areas of the DNA sequence that are robustly related with the age at which we have our first child, and the total number of children we have during the course of our life. The study includes an analysis of 62 datasets with information from 238,064 men and women for age at first birth, and almost 330,000 men and women for the number of children. Until now, reproductive behavior was thought to be mainly linked to personal choices or social circumstances and environmental factors. However, this new research shows that genetic variants can be isolated and that there is also a biological basis for reproductive behavior.

Youthful DNA in old age Science Daily - September 22, 2016

The DNA of young people is regulated to express the right genes at the right time. With the passing of years, the regulation of the DNA gradually gets disrupted, which is an important cause of aging. A study of over 3,000 people shows that this is not true for everyone: there are people whose DNA appears youthful despite their advanced years.

Erasing unpleasant memories with a genetic switch Science Daily - June 30, 2016

Dementia, accidents, or traumatic events can make us lose the memories formed before the injury or the onset of the disease. Researchers have now shown that some memories can also be erased when one particular gene is switched off. In the reported study, the mice were trained to move from one side of a box to the other as soon as a lamp lights up, thus avoiding a foot stimulus. This learning process is called associative learning. Its most famous example is Pavlov's dog: conditioned to associate the sound of a bell with getting food, the dog starts salivating whenever it hears a bell. When the scientists switched off the neuroplastin gene after conditioning, the mice were no longer able to perform the task properly. In other words, they showed learning and memory deficits that were specifically related to associative learning. The control mice with the neuroplastin gene switched on, by contrast, could still do the task perfectly.

Researchers explore epigenetic influences of chronic pain Medical Express - June 21, 2016

Researchers at Drexel University College of Medicine are aiming to identify new molecular mechanisms involved in pain. Their latest study, published this month in Epigenetics & Chromatin, shows how one protein - acting as a master controller - can regulate the expression of a large number of genes that modulate pain. Epigenetics

First happiness genes have been located Science Daily - April 25, 2016

For the first time in history, researchers have isolated the parts of the human genome that could explain the differences in how humans experience happiness. These are the findings of a large-scale international study in over 298,000 people. The researchers found three genetic variants for happiness, two variants that can account for differences in symptoms of depression, and eleven locations on the human genome that could account for varying degrees of neuroticism. The genetic variants for happiness are mainly expressed in the central nervous system and the adrenal glands and pancreatic system. The results were published in the journal Nature Genetics.

More ancient viruses lurk in our DNA than we thought PhysOrg - March 22, 2016

Think your DNA is all human? Think again. And a new discovery suggests it's even less human than scientists previously thought. Think your DNA is all human? Think again. And a new discovery suggests it's even less human than scientists previously thought. Whether or not it can replicate, or reproduce, it isn't yet known. But other studies of ancient virus DNA have shown it can affect the humans who carry it. n addition to finding these new stretches, the scientists also confirmed 17 other pieces of virus DNA found in human genomes by other scientists in recent years. The study looked at the entire span of DNA, or genome, from people from around the world, including a large number from Africa - where the ancestors of modern humans originated before migrating around the world. The team used sophisticated techniques to compare key areas of each person's genome to the reference human genome.

Innate teaching skills 'part of human nature', study says PhysOrg - February 8, 2016

Some 40 years ago, Washington State University anthropologist Barry Hewlett noticed that when the Aka pygmies stopped to rest between hunts, parents would give their infants small axes, digging sticks and knives. To parents living in the developed world, this could be seen as irresponsible. But in all the intervening years, Hewlett has never seen an infant cut him- or herself. He has, however, seen the exercise as part of the Aka way of teaching, an activity that most researchers - from anthropologists to psychologists to biologists - consider rare or non-existent in such small-scale cultures. He has completed a small but novel study of the Aka, concluding that, teaching is part of the human genome.

Genes for a longer, healthier life found Science Daily - December 1, 2015

Out of a 'haystack' of 40,000 genes from three different organisms, scientists have found genes that are involved in physical aging. If you influence only one of these genes, the healthy lifespan of laboratory animals is extended -- and possibly that of humans, too. DNA strand. Driven by the quest for eternal youth, humankind has spent centuries obsessed with the question of how it is exactly that we age. With advancements in molecular genetic methods in recent decades, the search for the genes involved in the aging process has greatly accelerated.

Heart disease gene 'found in women' BBC - October 21, 2015

Scientists have identified a gene that puts women at higher risk of heart disease, an early study suggests. The work showed that women who had a particular version of the BCAR1 gene were more likely than other women to have heart attacks and strokes. In contrast, men who had the gene were not at increased risk.

Extra DNA acts as a 'spare tire' for our genomes Science Daily - July 6, 2015

Carrying around a spare tire is a good thing -- you never know when you'll get a flat. Turns out we're all carrying around 'spare tires' in our genomes, too. Today researchers report that an extra set of guanines (or 'G's) in our DNA may function just like a 'spare' to help prevent many cancers from developing.

Longer Life May Lie in Number of Anti-Inflammatory Genes Live Science - April 8, 2015

Why do some kinds of animals live longer than others? For mammals, part of the answer may lie in the number of anti-inflammatory genes. From mouse to man - and across 12 other mammal species examined - researchers found that those with more copies of genes called CD33rSIGLEC, which is involved in fighting inflammation, have a longer life span. Moreover, mice that researchers bred to have fewer copies of these genes experience premature aging and early death compared with normal mice, the study found.

Breast Cancer Genes: How Much Risk Do BRCA Mutations Bring? Live Science - April 8, 2015