The Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties of ancient Egypt are often combined under the group title, New Kingdom. This dynasty is considered to be the last one of the New Kingdom of Egypt, and was followed by the Third Intermediate Period.

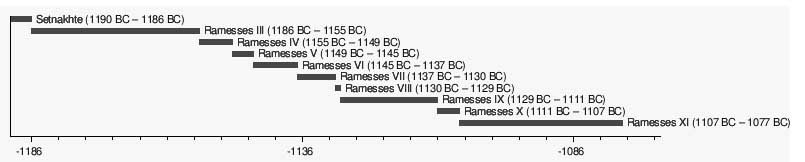

The Pharaohs of the 20th dynasty ruled for approximately one hundred and twenty years: from ca 1187 to 1064 BC. The dates and names in the table are taken from Dodson and Hilton. Many of the pharaohs were buried in the Valley of the Kings in Thebes (designated KV). More information can be found on the Theban Mapping Project website.

Background

Pharaoh Setnakhte was likely already middle aged when he took the throne after Queen Twosret. He only ruled for a short time when he was succeeded by his son Ramesses III. Egypt was threatened by the Sea Peoples during this time period, but Ramesses III was able to defeat this confederacy from the Near East. The king is also known for a harem conspiracy in which Queen Tiye attempted to assassinate the king and put her son Pentawere on the throne. The coup was not successful in the end. The king may have died from the attempt on his life, but it was his legitimate heir Ramesses IV who succeeded him to the throne. After this a succession of kings named Ramesses take the throne, but none would truly achieve greatness.

Tomb Robbing

The period of these rulers is notable for the beginning of the systematic robbing of the Royal Tombs. Many surviving administrative documents from this period are records of investigations and punishment for these crimes, especially in the reigns of Ramses IX and Ramses XI.

Decline

As happened under the earlier Nineteenth Dynasty, this group struggled under the effects of the bickering between the heirs of Ramesses III. For instance, three different sons of Ramesses III are known to have assumed power as Ramesses IV, Ramesses VI and Ramesses VIII respectively. However, at this time Egypt was also increasingly beset by a series of droughts, below-normal flooding levels of the Nile, famine, civil unrest and official corruption Ð all of which would limit the managerial abilities of any king. The power of the last king, Ramesses XI, grew so weak that in the south the High Priests of Amun at Thebes became the effective defacto rulers of Upper Egypt, while Smendes controlled Lower Egypt even before Ramesses XI's death. Smendes would eventually found the Twenty-First dynasty at Tanis.

The Twentieth dynasty of Egypt was the last of the New Kingdom of Egypt. The familial relationships are unclear, especially towards the end of the dynasty.

Userkhaure-setepenre Setnakhte (or Setnakht) was the first Pharaoh (1190 BC - 1186 BC) of the Twentieth Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt and the father of Ramesses III.

Setnakhte was not the son, brother or a direct descendant of the previous 2 pharaohs: either Twosret or Merneptah Siptah, nor that of Siptah's predecessor Seti II, whom Setnakht formally considered the last legitimate ruler. It is possible that he was an usurper who seized the throne during a time of crisis and political unrest, or he could have been a member of a minor line of the Ramesside royal family who emerged as Pharaoh.

He married Queen Tiy-merenese, perhaps a daughter of Merenptah. A connection between Setnakhte's successors and the preceding 19th dynasty is suggested by the fact that one of Ramesses II's children also bore this name and that similar names are shared by Setnakhte's descendants such as Ramesses, Amun-her-khepshef, Seth-her-khepshef and Monthu-her-khepshef.

Setnakhte was originally believed to have enjoyed a reign of only two years based upon his Year 2 Elephantine stela but his third regnal year is now attested in Inscription No.271 on Mount Sinai. If his theoretical accession date is assumed to be II Shemu 10, based on the date of his Elephantine stela, Setnakhte would have ruled Egypt for at least two years and 11 months before he died, or nearly three full years. This date is only three months removed from Twosret's highest known date of Year 8, III Peret 5, and is based upon a calculation of Ramesses III's known accession date of I Shemu 26. Peter Clayton also assigned Setnakhte a reign of three years in his 1994 book on the Egyptian Pharaohs.

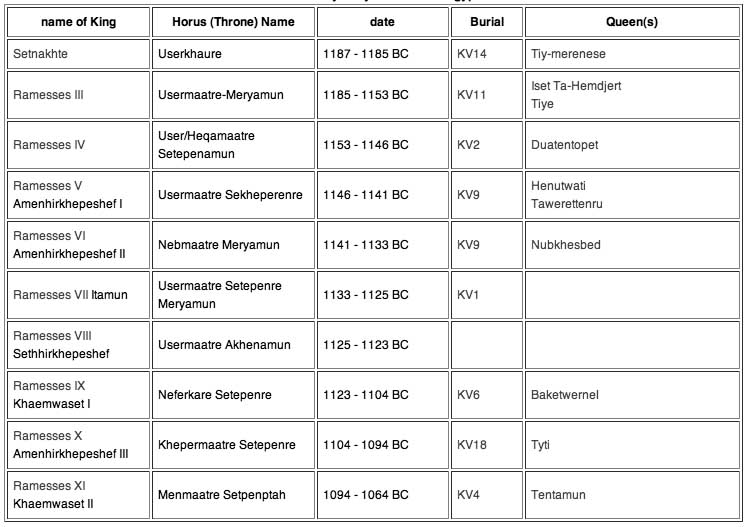

In a mid-January 2007 issue of the Egyptian weekly Al-Ahram, however, Egyptian antiquity officials announced that a recently discovered and well preserved quartz stela belonging to the High Priest of Amun Bakenkhunsu was explicitly dated to Year 4 of Setnakhte's reign. Consequently, Setnakhte likely ruled Egypt for around 4 years. Zahi Hawass, the current Secretary general of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities declared the discovery to be one of the most important finds of 2006 because "it adjusts the history of the 20th dynasty and reveals more about the life of Bakenkhunsu." As Setnakhte's reign was short, he may have come to the throne fairly late in life.

While Setnakhte's reign was still comparatively brief, it was just long enough for him to stabilize the political situation in Egypt and establish his son, Rameses III, as his successor to the throne of Egypt. The Bakenkhunsu stela reveals that it was Setnakhte who began the construction of a Temple of Amun-Re in Karnak which was eventually completed by his son, Ramesses III.

Setnakhte also started work on a tomb, KV11, in the Valley of the Kings, but stopped it when the tombcarvers accidentally broke into the tomb of the Nineteenth Dynasty Pharaoh Amenmesse. Setnakhte then appropriated the tomb of Queen Twosret (KV14), his predecessor, for his own use. Setnakhte's origins are unknown, and he may have been a commoner, although many Egyptologists believe he was related to the previous dynasty, the Nineteenth, through his mother and may thus have been a grandson of Ramesses II. Setnakhte's son and successor, Ramesses III, is regarded as the last great king of the New Kingdom.

The beginning of the Great Harris Papyrus or Papyrus Harris I, which documents the reign of Ramesses III, provides some details about Setnakhte's rise to power. An excerpt of James Henry Breasted's 1906 translation of this document is provided below:

"But when the gods inclined themselves to peace, to set the land in its rights according to its accustomed manner, they established their son, who came forth from their limbs, to be ruler, LPH, of every land, upon their great throne, Userkhaure-setepenre-meryamun, LPH, the son of Re, Setnakht-merire-meryamun, LPH. He was Khepri-Set, when he is enraged; he set in order the entire land which had been rebellious; he slew the rebels who were in the land of Egypt; he cleansed the great throne of Egypt; he was ruler of the Two Lands, on the throne of Atum. He gave ready faces to those who had been turned away. Every man knew his brother who had been walled in. He established the temples in possession of divine offerings, to offer to the gods according to their customary stipulations."

Setnakhte's stela from Elephantine touches on this chaotic period and refers explicitly to the expulsion of certain Asiatics, who fled, abandoning the gold which they looted from Egyptian temples behind. It is uncertain the degree to which this inscription referred to contemporary events or rather repeated anti-Asiatic sentiment from the reign of Pharaoh Ahmose I. Setnakhte identified with the God Atum or Temu, and built a temple to this God at Per-Atum.

Setnakhte may have been the first Pharaoh mentioned in Greek mythology. Marianne Luban quotes Diodorus Siculus: "A man of obscure origin was chosen king, whom the Egyptians call 'Ketes', but who among the Greeks is thought to be that Proteus who lived at the time of the war about Ilium." Ketes, from Egyptian Khenti, means the same as Proteios, meaning "first". King Setnakht may have been a commoner or a prince of royal blood who was somehow connected to the 19th Dynasty.

After his death, Setnakhte was buried in KV14 which was originally designed to be Twosret's royal tomb.

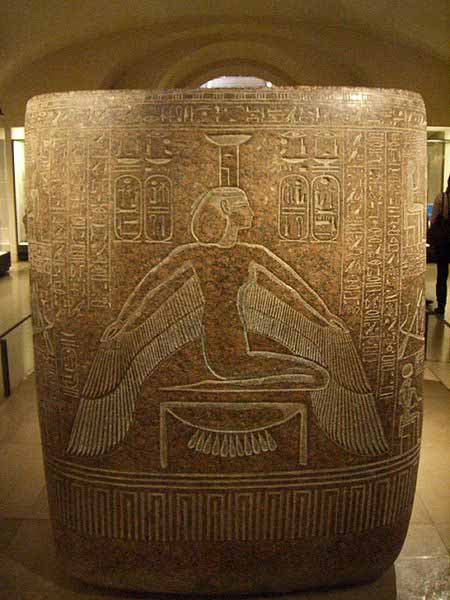

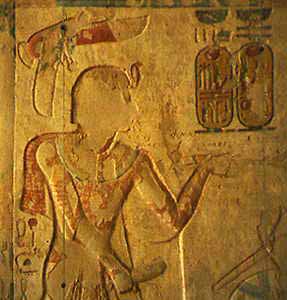

Relief from the Sanctuary of Khonsu Temple at Karnak

Usimare Ramesses III (also written Ramses and Rameses) was the second Pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty and is considered to be the last great New Kingdom king to wield any substantial authority over Egypt. He was the son of Setnakhte and Queen Tiy-Merenese. Ramesses III is believed to have reigned from March 1186 to April 1155 BCE. This is based on his known accession date of I Shemu day 26 and his death on Year 32 III Shemu day 15, for a reign of 31 years, 1 month and 19 days. (Alternate dates for this king are 1187 to 1156 BCE).

During his long tenure in the midst of the surrounding political chaos of the Greek Dark Ages, Egypt was beset by foreign invaders (including the so-called Sea Peoples and the Libyans) and experienced the beginnings of increasing economic difficulties and internal strife which would eventually lead to the collapse of the Twentieth Dynasty.

In Year 8 of his reign, the Sea Peoples, including Peleset, Denyen, Shardana, Meshwesh of the sea, and Tjekker, invaded Egypt by land and sea. Ramesses III defeated them in two great land and sea battles. Although the Egyptians had a reputation as poor seamen they fought tenaciously. Rameses lined the shores with ranks of archers who kept up a continuous volley of arrows into the enemy ships when they attempted to land on the banks of the Nile. Then the Egyptian navy attacked using grappling hooks to haul in the enemy ships. In the brutal hand to hand fighting which ensued, the Sea People were utterly defeated.

Ramesses III claims that he incorporated the Sea Peoples as subject peoples and settled them in Southern Canaan, although there is no clear evidence to this effect; the pharaoh, unable to prevent their gradual arrival in Canaan, may have claimed that it was his idea to let them reside in this territory. Their presence in Canaan may have contributed to the formation of new states in this region such as Philistia after the collapse of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. Ramesses III was also compelled to fight invading Libyan tribesmen in two major campaigns in Egypt's Western Delta in his Year 6 and Year 11 respectively.

The heavy cost of these battles slowly exhausted Egypt's treasury and contributed to the gradual decline of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. The severity of these difficulties is stressed by the fact that the first known labor strike in recorded history occurred during Year 29 of Ramesses III's reign, when the food rations for the Egypt's favoured and elite royal tomb-builders and artisans in the village of Set Maat her imenty Waset (now known as Deir el Medina), could not be provisioned.

Something in the air (but not necessarily Hekla 3) prevented much sunlight from reaching the ground and also arrested global tree growth for almost two full decades until 1140 BCE. The result in Egypt was a substantial inflation in grain prices under the later reigns of Ramesses VI-VII whereas the prices for fowl and slaves remained constant. The cooldown, hence, affected Ramesses III's final years and impaired his ability to provide a constant supply of grain rations to the workman of the Deir el-Medina community.

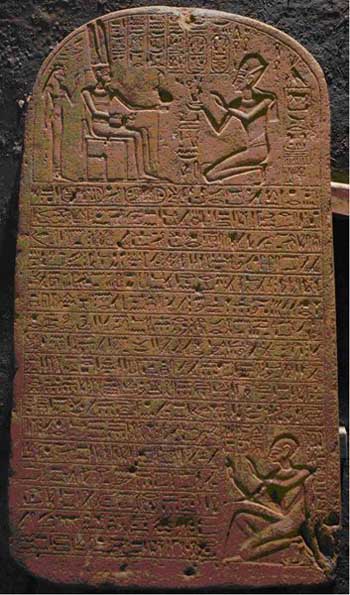

These difficult realities are completely ignored in Ramesses' official monuments, many of which seek to emulate those of his famous predecessor, Ramesses II, and which present an image of continuity and stability. He built important additions to the temples at Luxor and Karnak, and his funerary temple and administrative complex at Medinet-Habu is amongst the largest and best-preserved in Egypt; however, the uncertainty of Ramesses' times is apparent from the massive fortifications which were built to enclose the latter. No Egyptian temple in the heart of Egypt prior to Ramesses' reign had ever needed to be protected in such a manner.

Thanks to the discovery of papyrus trial transcripts (dated to Ramesses III), it is now known that there was a plot against his life as a result of a royal harem conspiracy during a celebration at Medinet Habu. The conspiracy was instigated by Tiye, one of his two known wives (the other being Iset Ta-Hemdjert), over whose son would inherit the throne. Iset's son, Ramesses (the future Ramesses IV), was the eldest and the successor chosen by Ramesses III in preference to Tiy's son Pentaweret.

The trial documents emphasize the extensive scale of the conspiracy to assassinate the king since many individuals were implicated in the plot. Chief among them were Queen Tey and her son Pentaweret, Ramesses' chief of the chamber, Pebekkamen, seven royal butlers (a respectable state office), two Treasury overseers, two Army standard bearers, two royal scribes and a herald. There is little doubt that all of the main conspirators were executed: some of the condemned were given the option of committing suicide (possibly by poison) rather than being put to death.

According to the surviving trials transcripts, 3 separate trials were started in total while 38 people were sentenced to death. The tombs of Tiy and her son Pentaweret were robbed and their names erased to prevent them from enjoying an afterlife. The Egyptians did such a thorough job of this that the only references to them are the trial documents and what remains of their tombs.

Some of the accused harem women tried to seduce the members of the judiciary who tried them but were caught in the act. Judges who took part in the carousing were severely punished.

Historian Susan Redford speculates that Pentawere, being a noble, was given the option to commit suicide by taking poison and so be spared the humiliating fate of some of the other conspirators who would have been burned alive with their ashes strewn in the streets. Such punishment served to make a strong example since it emphasized the gravity of their treason for ancient Egyptians who believed that one could only attain an afterlife if one's body was mummified and preserved - rather than being destroyed by fire.

In other words, not only were the criminals killed in the physical world; they did not attain an afterlife. They would have no chance of living on into the next world, and thus suffered a complete personal annihilation. By committing suicide, Pentawere could avoid the harsher punishment of a second death. This could have permitted him to be mummified and move on to the afterlife.

It is not known if the assassination plot succeeded. However, Ramesses III died in his 32nd year before the summaries of the sentences were composed, but the same year that the trial documents record the trial and execution of the conspirators.

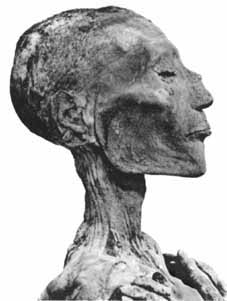

Although it was long believed that Ramesses III's body showed no obvious wounds, a recent examination of the mummy by a German forensic team, televised in the documentary Rameses on the Science Channel in 2011, showed excess bandages around the neck. A subsequent CT Scan revealed that beneath the bandages was a deep knife wound across the throat, a wound deep enough to reach the vertebrae. According to the documentary narrator, "It was a wound no one could have survived."

Prior to this discovery, it had been speculated that Ramesses III may have been killed by means that would not have left a mark on the body. Among the conspirators were practitioners of magic, who might well have used poison. Some have put forth a hypothesis that a snakebite from a viper was the cause of the king's death but this proposal has not been proven. His mummy includes an amulet to protect Ramesses III in the afterlife from snakes. The servant in charge of his food and drink were also among the listed conspirators, but there were also other conspirators who were called the snake and the lord of snakes.

In one respect the conspirators certainly failed. The crown passed to the king's designated successor: Ramesses IV. Ramesses III may have been doubtful as to the latter's chances of succeeding him since, in the Great Harris Papyrus, he implored Amun to ensure his son's rights.

King Ramesses III's throat was slit, analysis reveals BBC - December 18, 2012

Conspirators murdered Egyptian King Ramesses III by slitting his throat, experts now believe, based on a new forensic analysis. The first CT scans to examine the king's mummy reveal a cut to the neck deep enough to be fatal. The secret has been hidden for centuries by the bandages covering the mummy's throat that could not be removed for preservation's sake.

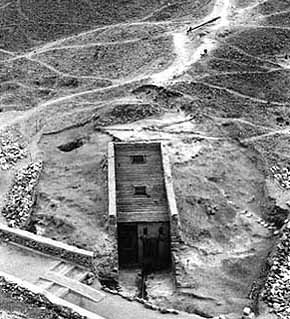

Aerial View

Ceiling

Sarcophagus

The mummy of Ramesses III was discovered by antiquarians in 1886 and is regarded as the prototypical Egyptian Mummy in numerous Hollywood movies. His tomb (KV11) is one of the largest in the Valley of the Kings

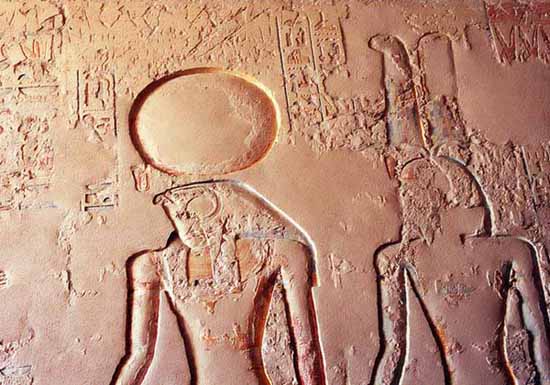

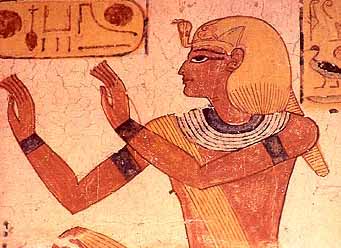

Relief of Ramesses IV at the Temple of Khonsu in Karnak

Limestone ostracon depicting Ramesses IV smiting his enemies.

Heqamaatre Ramesses IV (also written Ramses or Rameses) was the third pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt. His name prior to assuming the crown was Amonhirkhopshef. He was the fifth son of Ramesses III and was appointed to the position of crown prince by the twenty-second year of his father's reign when all four of his elder brothers predeceased him.

As his father's chosen successor the Prince employed three distinctive titles: "Hereditary Prince", "Royal scribe" and "Generalissimo"; the latter two of his titles are mentioned in a text at Amenhotep III's temple at Soleb and all three royal titles appear on a lintel now in Florence, Italy. As heir-apparent he took on increasing responsibilities; for instance, in Year 27 of his father's reign, he is depicted appointing a certain Amenemopet to the important position of Third Prophet of Amun in the latter's TT 148 tomb. Amenemope's Theban tomb also accords prince Ramesses all three of his aforementioned sets of royal titles. Due to the three decade long rule of Ramesses III, Ramesses IV is believed to have been a man in his forties when he took the throne. His rule has been dated to either 1151 to 1145 BC or 1155 to 1149 BC.

Ramesses IV's mother is today most likely Queen Tyti from recently discovered notes published in the 2010 issue of the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. They reveal that Tyti who was both a king's daughter, a king's wife and a king's mother in her own right--was identified in Papyrus BM EA 10052 (ie. the tomb-robbery papyri) to be a queen of Ramesses III, Ramesses IV's father. The 2010 JEA authors write that since Ramesses VI's mother is known to be a certain lady named Iset Ta-Hemdjert or Isis.

Thus the identity of Ramesses IV's mother has been resolved in favour of Queen Tyti who was once erroneously thought to be the mother of another king in the mid-1980's: Ramesses XI. Ramesses IV was succeeded to the throne by his son Ramesses V.

At the start of his reign, the pharaoh initiated a substantial building campaign program on the scale of Ramesses II by doubling the size of the work gangs at Deir el-Medina to a total of 120 men and dispatching numerous expeditions to the stone quarries of Wadi Hammamat and the turquoise mines of the Sinai.

The Great Rock stela of Ramesses IV at Wadi Hammamat records that the largest expedition - dated to his Year 3, third month of Shemu day 27 - consisted of 8,368 men alone including 5,000 soldiers, 2,000 personnel of the Amun temples, 800 Apiru and 130 stonemasons and quarrymen under the personal command of the High Priest of Amun, Ramessesnakht. The scribes who composed the text conscientiously noted that this figure excluded 900 men "who are dead and omitted from this list."

Consequently, once this omitted figure is added to the tally of 8,368 men who survived the Year 3 quarry expedition, a total of 900 men out of an original expedition of 9,268 men perished during this massive endeavor for a mortality rate of almost 10%. This gives an indication of the harshness of life in Egypt's stone quarries. Some of the stones which were dragged 60 miles to the Nile from Wadi Hammamat weighed 40 tons or more. Other Egyptian quarries including Aswan were located much closer to the Nile which enabled them to use barges to transport stones long distances.

Part of the king's program included the extensive enlargement of his father's Temple of Khonsu at Karnak and the construction of a large mortuary temple near the Temple of Hatshepsut. Ramesses IV also sent several expeditions to the turquoise mines the Sinai; a total of four expeditions are known prior to his fourth year.

The Serabit el-Khadim stela of the Royal Butler Sobekhotep states: "Year 3, third month of Shomu. His Majesty sent his favored and beloved one, the confident of his lord, the Overseer of the Treasury of Silver and Gold, Chief of the Secrets of the august Palace, Sobekhotep, justified, to bring for him all that his heart desired of turquoise (on) his fourth expedition." This expedition dates to either Ramesses III or IV's reign since Sobekhotep is attested in office until at least the reign of Ramesses V.

Ramesses IV's final venture to the turquoise mines of the Sinai is documented by the stela of a senior army scribe named Panufer. Panufer states that this expedition's mission was both to procure turquoise and to establish a cult chapel of king Ramesses IV at the Hathor temple of Serabit el-Khadim.

Ramesses IV is attested by his aforementioned building activity at Wadi Hammamat and Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai as well as several papyri and even one obelisk. The creation of a royal cult in the Temple of Hathor is known under his reign at Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai while Papyrus Mallet (or P. Louvre 1050) dates to Years 3 and 4 of his reign.[4] Papyrus Mallet is a six column text dealing partly with agricultural affairs; its first column lists the prices for various commodities between Year 31 of Ramesses III until Year 3 of Ramesses IV.

The final four columns contain a memorandum of 2 letters composed by the Superintendent of Cattle of the Estate of Amen-Re, Bakenkhons, to several mid-level administrators and their subordinates. Meanwhile, surviving monuments of Ramesses IV in the Delta consists of an obelisk recovered in Cairo and a pair of his cartouches found on a pylon gateway both originally from Heliopolis.

The most important document to survive from this pharaoh's rule is Papyrus Harris I, which honors the life of his father, Ramesses III, by listing the latter's many accomplishments and gifts to the temples of Egypt, and the Turin papyrus, the earliest known geologic map. Ramesses IV was perhaps the last New Kingdom king to engage in large-scale monumental building after his father as "there was a marked decline in temple building even during the longer reigns of Ramesses IX and VI. The only apparent exception was the attempt of Ramesses V and VI to continue the vast and uncompleted mortuary temple of Ramesses IV at the Assasif."

Despite Ramesses IV's many endeavours for the gods and his prayer to Osiris - preserved on a Year 4 stela at Abydos - that "thou shalt give me the great age with a long reign as my predecessor", the king did not live long enough to accomplish his ambitious goals.

After a short reign of about six and a half years, Ramesses IV died and was buried in tomb KV2 in the Valley of the Kings. His mummy was found in the royal cache of Amenhotep II's tomb KV35 in 1898.[19] His chief wife is Queen Duatentopet or Tentopet who was buried in QV74. His son, Ramesses V, would succeed him to the throne.

Usermare Sekhepenre Ramesses V (also written Ramses and Rameses) was the fourth pharaoh of the Twentieth dynasty of Egypt and was the son of Ramesses IV and Queen Duatentopet.

His reign was characterized by the continued growth of the power of the priesthood of Amun, which controlled much of the temple land in the country and state finances at the expense of Pharaoh. The Turin 1887 papyrus records a financial scandal during his reign that involved the priests of Elephantine. A period of domestic instability also afflicted his reign since Turin Papyrus Cat. 2044 states that the workmen of Deir el-Medina periodically stopped work on Ramesses V's KV9 tomb in this king's first regnal year out of fear of "the enemy", presumably Libyan raiding parties, who had reached the town of Per-Nebyt and "burnt its people." Another incursion by these raiders into Thebes is recorded a few days later. This shows that the Egyptian state was having difficulties ensuring the security of its own elite tomb workers, let alone the general populace, during this troubled time.

The great Wilbour Papyrus, dating to Year 4 of his reign, was a major land survey and tax assessment document which covered various lands "extending from near Crocodilopolis (Medinet el-Fayyum) southwards to a little short of the modern town of El-Minya, a distance of some 90 miles." It reveals most of Egypt's land was controlled by the Amun temples which also directed the country's finances. The document highlights the increasing power of the High Priest of Amun Ramessesnakht whose son, a certain Usimare'nakhte, held the office of chief tax master.

The circumstances of Ramesses V's death are unknown but it is believed he had a reign of almost 4 full years. It is possible he was dethroned by his successor, Ramesses VI because Ramesses VI usurped his predecessor's KV9 tomb. An ostracon records that this king was only buried in Year 2 of Ramesses VI which was highly irregular since Egyptian tradition required a king to be mummified and buried precisely 70 days into the reign of his successor.

However, another reason for the much delayed burial of Ramesses V in Year 2, second month of Akhet day 1 of Ramesses VI's reign may have been connected with Ramesses VI's need "to clear out any Libyans invaders from Thebes and to provide a temporary tomb for Ramesses V until plans for a double burial within tomb KV9 could be put into effect." Moreover, a Theban work journal dated to Year 2 of Ramesses VI's reign shows that a period of normality had returned to the Theban West Bank by this time.

The mummy of Ramesses V's was recovered in 1898 and seems to indicate that he suffered from smallpox due to lesions found on his face and this is thought to have caused his death. He is thought to be one of the earliest known victims of poxvirus.

Ramesses VI (also written Ramses and Rameses) was the fifth ruler of the Twentieth dynasty of Egypt who reigned from 1145 BC to 1137 BC and a son of Ramesses III by Iset Ta-Hemdjert. His royal tomb, KV9, is located near Tutankhamun's tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

Ramesses' prenomen or royal name was Nebmaatre-meryamun meaning "Lord of Justice is Re, Beloved of Amun" while his royal epithet - Amunherkhepshef Netjer-heqa-iunu - translates as "Amun is his Strength, God Ruler of Heliopolis. His 8th Regnal Year is attested in a graffito which names the then serving High Priest of Amun, Ramessessnakht. Based on Raphael Ventura's successful reconstruction of Turin Papyrus 1907+1908, Ramesses VI is generally assumed to have enjoyed a reign of 8 full Years. The latest scholarly publication on Egyptian chronology in 2006 also assigned Ramesses VI 8 years of rule. He lived for two months into his brief 9th Regnal year before dying and was succeeded by his son, Ramesses VII.

Ramesses VI's chief queen was Nubkhesbed who is "mentioned on a stela of Iset E (her daughter) from Koptos, and also in tomb KV13 in the Valley of the Kings." This pharaoh would be succeeded on the throne by his son Ramesses VII.

Egypt's political and economic decline continued unabated during Ramesses VI's reign; he is the last king of Egypt's New Kingdom whose name is attested in the Sinai. At Thebes, the power of the chief priests of Amun Ramessesnakht grew at the expense of Pharaoh despite the fact that Isis, Ramesses VI's daughter, was connected to the Amun priesthood "in her role as God's Wife of Amun or Divine Adoratice."

Shortly after his burial, his tomb was penetrated and ransacked by grave robbers who hacked away at his hands and feet in order to gain access to his jewelry. A medical examination of his mummy which was found in KV35 in 1898 revealed severe damage to his body, with the head and torso being broken into several pieces by an axe used by the tomb robbers. This damage was caused by tomb robbers who were robbing the dead king's body of his jewelry. The creation of Ramesses VI's tomb, however, protected Tutankhamen's own intact tomb from grave robbers since debris from its formation was dumped over the tomb entrance to the boy king's tomb.

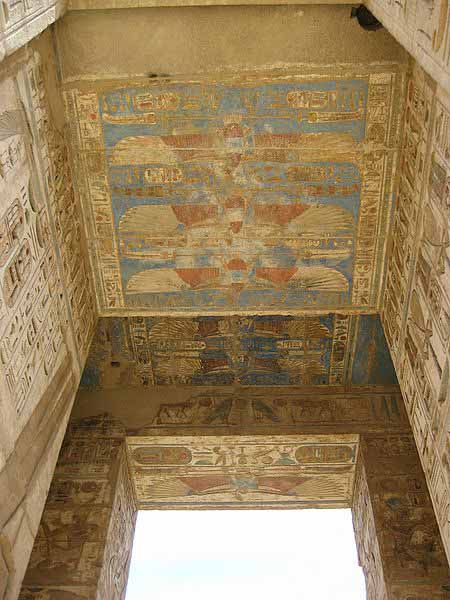

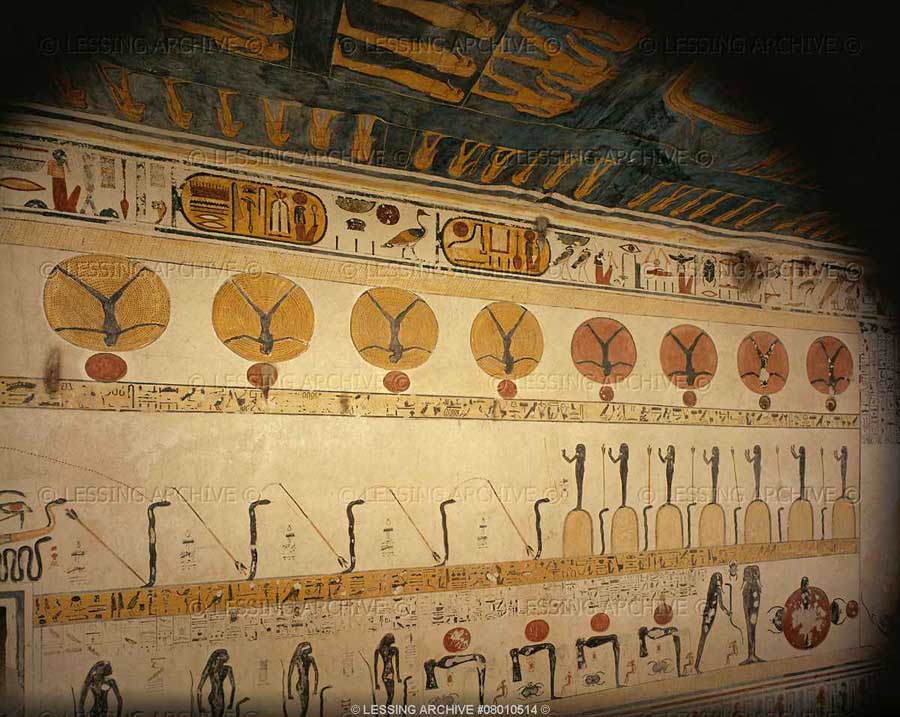

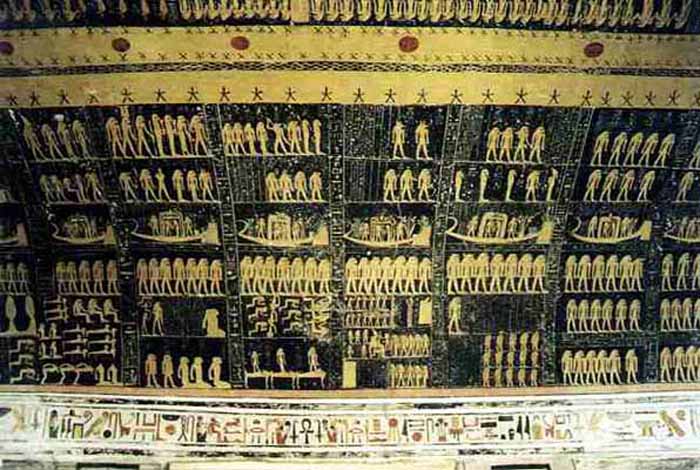

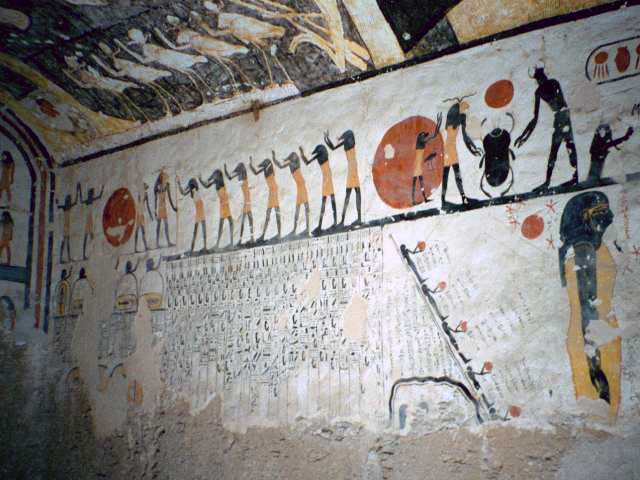

The tomb of Ramesses V (KV 9) is one of the most interesting tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Its decorations represent sort of a treatise on theology, in which the fundamental elements are the sun and its daily journey in the world of darkness. In general, the decorations provide the story of the origins of the heavens, earth, the creation of the sun, light and life itself. The decorative plan for this tomb is one of the most sophisticated and complete in the Valley of the Kings.

However, as it turns out, Ramesses VI was not much of a tomb builder, for this tomb was originally build by his predecessor, Ramesses V.

It was only enlarged by Ramesses VI. Why Ramesses VI did not build his own tomb, as was certainly the tradition, is unknown to us. However, the inscriptions for Ramesses V found in the first parts of the tomb were not usurped, and it is clear that the brothers probably shared a common theology.

The tomb has been known of since antiquity, attested to by numerous graffiti. It was known to the Romans as the tomb of Memnon, and to the scholars of the Napoleonic Expedition as La Tombe de la Metempsychose. It was cleared of debris by George Daressy in 1888.

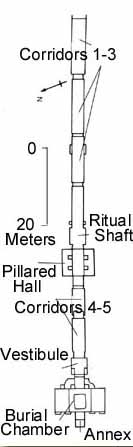

The tomb itself is somewhat simplistic, with no true stairways, but otherwise similar to other 20th Dynasty tombs. There are three corridors that lead to the ritual shaft, and then to a four pillared hall. This is followed by by two more corridors, a vestibule and then the burial chamber with its single annex at the rear. The last corridor (number 5) is unique, as the floor is sloping while the roof is horizontal.This was done to avoid part of tomb KV 12.

In this tomb, astronomical ceilings are found in each passage. The walls of the first through third corridors are painted with images from the Book of Gates and the Book of Caverns, a theme which is continued on into the vestibule.

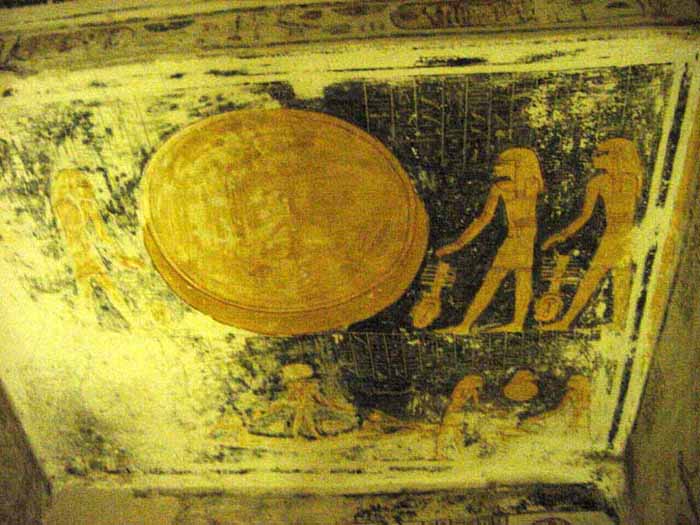

The beginning of the first corridor has a scene of the king making offerings to Ra-Horakhty followed by Osiris, now shown on both sides of the corridor.

But rather then the Litany of Ra, the Book of Gates follows on the south wall and the Book of Caverns on the north. In the fourth and fifth corridors there are also passages from the Book of Amduat, and in the vestibule passages from the Book of the Dead. The walls of the burial chamber, where there is to be found a broken sarcophagus, are painted with illustrations from the Book of the Earth, while the astronomical ceiling have decorations from the Book of the Day and the Book of the Night. While the decorations are well colored with sunk reliefs, stylistically the art is inferior to most of the 19th Dynasty tombs.

Usermaatre Meryamun Setepenre Ramesses VII (also written Ramses and Rameses) was the sixth pharaoh of the 20th dynasty of Ancient Egypt. He reigned from about 1136 to 1129 BC and was the son of Ramesses VI. Other dates for his reign are 1138-1131 BC. The Turin Accounting Papyrus 1907+1908 is dated to Year 7 of his reign and states that 11 full years passed from Year 5 of Ramesses VI to Year 7 of his reign.

Ramesses VII's seventh year is also attested in Ostraca O. Strasbourg h 84 which is dated to II Shemu of his 7th Regnal Year. In 1980, C.J. Eyre proposed that a Year 8 papyri belonged to the reign of Ramesses VII. This papyri, dated anonymously to a Year 8 IV Shemu day 25, details the record of the commissioning of some copper work and mentions 2 foreman at Deir El-Medina: Nekhemmut and Hormose.

The foreman Hormose was previously attested in office only during the reign of Ramesses IX while his father and predecessor in this post a certain Ankherkhau served in office from the second decade of the reign of Ramesses III through to Year 4 of Ramesses VII where he is shown acting with Nekhemmet and the scribe Horisheri. The new Year 8 papyri proves that Hormose succeeded to his father's office as foreman by Year 8 of a certain king but Dominique Valbelle has now argued that this document must rather be dated to the reign of Ramesses IX instead.

Since Ramesses VII's accession is known to have occurred around the end of III Peret, the king would have ruled Egypt for 7 years and 5 months when this document was drawn up provided that it belonged to his reign something which is now in dispute. At any rate, his reign must have lasted for a minimum of 6 years and 10 months or nearly 7 full years since the accession date of his successor Ramesses VIII has been fixed by Amin Amer to an 8 month period between I Peret day 2 and I Akhet day 13. Ramesses VII could easily have died on III Peret during this large interval for a reign of 7 full years.

Very little is known about his reign, though it was evidently a period of turmoil as grain prices soared to the highest level.

Ramesses VII was buried in Tomb KV1 upon his death. His mummy has never been found, though four cups inscribed with the pharaoh's name were found in the "royal cache" in DB320 along with the remains of other pharaohs.

Usermare Akhenamun Ramesses VIII (also written Ramses and Rameses) or Ramesses Sethherkhepshef Meryamun ('Set is his Strength, beloved of Amun') (at 1130-1129 BC, or simply 1130 BC as Krauss and Warburton date his reign), was the seventh Pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt and was one of the last surviving sons of Ramesses III.

Ramesses VIII is the most obscure ruler of this Dynasty and the current information from his brief kingship suggests that he lasted on the throne for one year at the most. Some scholars assign him a maximum reign of two years. The fact that he succeeded to power after the death of Ramesses VII - a son of Ramesses VI - may indicate a continuing problem in the royal succession. Ramesses VIII's prenomen or royal name, Usermaatre Akhenamun, means "Powerful is the Justice of Re, Helpful to Amun." Monuments from his reign are scarce and consist primarily of an inscription at Medinet Habu, a mention of this ruler in one document - Berlin stela 2081 of Hori at Abydos - and one scarab. His only known date is a Year 1, I Peret day 2 graffito in the tomb of Kyenebu at Thebes.

He is the sole pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty whose tomb has not been definitely identified in the Valley of the Kings, though some scholars have suggested that the tomb of Prince Mentuherkhepshef, KV19, the son of Ramesses IX, was originally started for Ramesses VIII but proved unsuitable when he became a king in his own right.

Ramesses IX (also written Ramses) (originally named Amon-her-khepshef Khaemwaset) (ruled 1129 - 1111 BC) was the eighth king of the Twentieth dynasty of Egypt. He was the third longest serving king of this Dynasty after Ramesses III and Ramesses XI. He is now believed to have assumed the throne on I Akhet day 21 based on evidence presented by Jurgen von Beckerath in a 1984 GM article.

According to Papyrus Turin 1932+1939, Ramesses IX enjoyed a reign of 18 Years and 4 months and died in his 19th Year in the first month of Peret between day 17 and 27. His throne name, Neferkare Setepenre, means "Beautiful Is The Soul of Re, Chosen of Re." Ramesses IX is believed to be the son of Mentuherkhepeshef, a son of Ramesses III since Montuherkhopshef's wife, the lady Takhat on the walls of tomb KV10 which she usurped and reused in the late 20th dynasty, bears the prominent title of King's Mother; no other 20th dynasty king is known to have had a mother with this name. Ramesses IX was, therefore, probably a grandson of Ramesses III.

His reign is best known for the Year 16 tomb robberies, recorded in the Abbott Papyrus, the Leopold II-Amherst Papyrus and the Mayer Papyri, when several royal and noble tombs in the Western Theban necropolis were found to have been robbed, including that of a 17th Dynasty king, Sobekemsaf I. Paser, Mayor of Eastern Thebes or Karnak, accused his subordinate Paweraa, the Mayor of West Thebes responsible for the safety of the necropolis, of being either culpable in this wave of robberies or negligent in his duties of protecting the Valley of the Kings from incursions by tomb robbers. Paweraa played a leading part in the vizierial commission set up to investigate, and, not surprisingly, it proved impossible for Paweraa to be officially charged with any crime due to the circumstantiality of the evidence. Paser disappeared from sight soon after the report was filed. Ramesses IX brought a measure of stability to Egypt after the wave of tomb robberies. He also paid close attention to Lower Egypt and built a substantial monument at Heliopolis.

In the sixth year of his reign, he inscribed his titulature in the Lower Nubian town of Amara West. Most of his building works centre on the sun temple centre of Heliopolis in Lower Egypt where the most significant monumental works of his reign are located. However, he also decorated the wall to the north of the Seventh Pylon in the Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak.

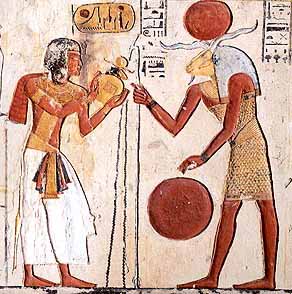

Relief of Ramesses IX at Karnak

Finally, his name has been found at the Dakhla Oasis in Western Egypt and Gezer at Palestine which may suggest a residual Egyptian influence in Asia; the majority of the New Kingdom Empire's possessions in Canaan and Syria had long been lost to the Sea Peoples by his reign. He is also known for having honored his predecessors Ramesses II, Ramesses III and Ramesses VII.

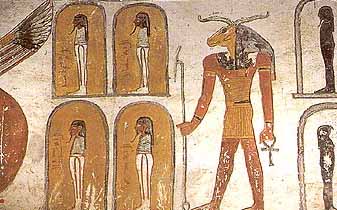

Ramesses IX is known to have had 2 sons: at Heliopolis, "a gateway was inscribed again with texts including the king's names and also those of the prince and High Priest Nebmaatre, who was fairly certainly his son." Ramesses IX's second son, Montuherkhopshef C, perhaps this king's intended heir, who did not live long enough to succeed his father, took over the former KV19 tomb of Sethirkhepsef B in the Valley of the Kings.

The throne was instead assumed by Ramesses X whose precise relationship to Ramesses IX is unclear. Ramesses X might have been Ramesses IX's son, but this assumption remains unproven. Anyway, tomb KV19, which was one of the most beautifully decorated tombs in the royal valley, had been abandoned by Sethirkhepsef B when the latter assumed the throne as king Ramesses VIII and one of prince Montuherkhopshef's depictions there "bears the prenomen cartouche to Ramesses IX on its belt" thereby establishing the identity of this prince's father.

The tomb of Ramesses IX, (KV6), has been open since antiquity, as is evidenced by the presence of Roman and Greek graffiti on the tomb walls. It is quite long in the tradition of the 'syringe' tunnels of the later 19th and 20th Dynasties and lies directly opposite the tomb of Ramesses II in the Valley of the Kings; this fact may have influenced Ramesses IX's choice of location for his final resting place due to its proximity to this great Pharaoh. While Ramesses IX's chief queen is not precisely identified in surviving Egyptian inscriptions, she was most likely Baketwernel.

In 1881, the mummy of Ramesses IX was found in the Deir el-Bahri cache (DB320) within one of the two coffins of Neskhons - wife of the Theban High Priest Pinedjem II. This pharaoh's mummy was not apparently examined by Grafton Elliot Smith and not included in his 1912 catalogue of the Royal Mummies. When the mummy was unwrapped, a bandage was found identifying the king as "Ra Khaemwaset" which was a reference to either Ramesses Khaemwaset Meryamun (IX) or Ramesses Khaemwaset Meryamun Neterheqainu (XI). But since an ivory box of Neferkare Ramesses IX was found in the royal cache itself, and Ramesses XI was probably never buried at Thebes but rather in Lower Egypt, "the royal mummy is most likely to be that of Ramesses IX himself." He was about 50 years old when he died and his mummy had suffered damage to its nose, which is missing.

The tomb of Ramesses IX (KV 6) is the first tomb one encounters within the modern entrance to the Valley of the Kings. It is a rather simplistic tomb in most respects, though the art work is interesting.

Entrance is made to the tomb down a corridor with steps on either side, which then connects to the first true corridor with two annexes on either side. However, one of the annexes was never completed. This is followed by a second and third corridor, prior to reaching a vestibule. Note the absence of a ritual shaft. The vestibule opens into a four pillared hall, and then a very short corridor which leads to the burial chamber with no annexes. It is possible that the burial chamber was originally meant to be another corridor, as it is very small, but was converted because of the kings death. An unusual feature of the burial chamber is a two tiered pit in the floor. No sarcophagus has ever been found.

The decorative theme for this tomb begins with the king's adoration of the sun disk, accompanied by Isis and Nephthys on the lintel over the entrance. Variations of this are also found on the door lintels of the second and third corridors. The art in this tomb is similar to that of Ramesses VI, though here, the first two corridors have passages from the Litany of Re, rather then the Book of Gates. It appears that only decorative theme of the first corridor was completed during Ramesses IX's lifetime, with the remainder of the artwork completed with much less care and skill after his death.

In the second and third corridors, in addition to the Litanies of Re, there are also passages from the Book of the Dead, the Book of Caverns, and in the last part, the Book of Amduat. Probably due not only to the changing concept of the Afterlife, but also the lack of space, most of the texts are abbreviated, and the Book of Gates does not show up at all. There are figures of two priests to either side of the door to the pillared hall representing the Opening of the Mouth ritual. The burial chamber has a vaulted ceiling with a double representation of Nut and passages from the Book of the Day and the Book of the Night.

There is little in the way of funerary equipment which was discovered in the tomb. No sarcophagus was found.

Khepermare Ramesses X (also written Ramses and Rameses) (ruled c. 1111 BC - 1107 BC) was the ninth ruler of the 20th dynasty of Ancient Egypt. His birth name was Amonhirkhepeshef. It is uncertain if his reign was 3 or 4 Years, but there is now a strong consensus among Egyptologists that it did not last as long as 9 Years, as was previously assumed. His prenomen or throne name, Khepermaatre, means "The Justice of Re Abides." The English Egyptologist Aidan Dodson states:

His KV18 tomb in the Valley of the Kings was left unfinished and it is uncertain if he was ever buried here since no remains or fragments of funerary objects were discovered within it.

Tomb KV18 in the Valley of the Kings on the West Bank at Luxor (Thebes) was cut for Ramesses X, the second to last ruler of Egypt's 20th Dynasty. It is located in the southwest wadi. The tomb was unfinished and has only recently been cleared, though apparently some amount of debris remains. It has had a number of visitors over the years, beginning with Richard Pococke in the early 1700s. No real funerary material of the owner has ever been discovered, and even the foundation deposits discovered by Howard Carter were uninscribed.

The tomb consists of little more than an entranceway and two corridors (that we know of). It was probably open during antiquity, before being buried under mud and rubble.

The entrance to the tomb continues with the Ramessid tendency to create ever larger facades, this one being some 10 cm (4 inches) wider than that of the previous king's tomb.

However, it is simple and has little slope. There was a divided stairway, though only a few steps remain. At the end of the entrance there was a step-down into the first corridor. Here, on the reveals and thickness of the doorjamb are the remains of the king's name.

The tomb's first corridor was blocked by the electric lighting installations for the Valley of the Kings which was housed there by Howard Carter in 1904. Here, Carter also had the walls whitewashed, and had a level base built as a foundation for the generating equipment! Furthermore, he constructed retaining walls at the sides and end of the chamber, adding additional roofing. Some of this equipment remains in the tomb today. There has been some ceiling collapse at the rear of this corridor. This corridor was originally fully cut and decorated.

The first corridor leads into a second corridor that was blocked by a modern wall which has recently been stripped away. There is a step down into this second corridor, that was never completely cut. There remains actual rough steps leading up to the abandoned workface. The ceiling here has collapsed, but a couple of large rectangular recess were cut in each wall near the ceiling.

Within the outer areas, little decoration remains. Due to flooding, the beautiful example of the Ramessid entrance motif of the king kneeling on either side of the sun disc on the horizon and ram headed god, along with attendant goddesses Isis and Nephthys) that was drawn by Champollion's artists in 1826 are lost to us.

Most of the plaster and paint have fallen away. Only a portion of the left-hand side of the design is still visible along with modern European graffiti probably dating from between 1623 and 1905 AD. Trances of other badly damaged scenes may be found in the first corridor on the east and west walls. These include a rough head of Re-Horakhty on the left wall of the first passage. On the right wall we can also recognize the king in front of Re-Horakhty and Meretseger, followed by a sun disk.

There are no decoration in the second corridor. The only artifacts we are aware of that have been removed from the tomb (area) are those found in the foundation deposit by Howard Carter. They included blue glazed models of tools, mostly, including according to Carter "adze, hoe and yoke".

We know know that Ramesses X was not put to rest in this tomb, though his mummy has never been found anywhere else, either.

Ramesses XI reigned from 1107 BC to 1078 BC or 1077 BC and was the tenth and final king of the Twentieth dynasty of Egypt. He ruled Egypt for at least 29 years although some Egyptologists think he could have ruled for as long as 30. The latter figure would be up to 2 years beyond this king's highest known date of Year 10 of the Whm-Mswt era or Year 28 of his reign.[2] One scholar, Ad Thijs, has even suggested that Ramesses XI reigned as long as 33 years - such is the degree of uncertainty surrounding the end of his long reign.

It is believed that Ramesses ruled into his Year 29 since a graffito records that the High Priest of Amun Piankhy returned to Thebes from Nubia on III Shemu day 23 - or just 3 days into what would have been the start of Ramesses XI's 29th regnal year. Piankhy is known to have campaigned in Nubia during Year 28 of Ramesses XI's reign (or Year 10 of the Whm Mswt) and would have returned home to Egypt in the following year.

Ramesses XI was once thought to be the son of Ramesses X by Queen Tyti who was a King's Mother, King's Wife and King's Daughter in her titles. However, recent scholarly research into certain copies of parts of the Harris papyrus (or Papyrus BM EA 10052) - made by Anthony Harris - which discusses a harem conspiracy against Ramesses III reveals that Tyti was rather a queen of pharaoh Ramesses III instead.

Hence, Ramesses XI's mother was not Tyti and although he could have been a son of his predecessor, this is not established either. Ramesses XI married Tentamun, the daughter of Nebseny, with whom he fathered Henuttawy - the future wife of the high priest Pinedjem I. Ramesses XI also had another daughter named Tentamun who became king Smendes' future wife in the next dynasty.

Ramesses XI's reign was characterized by the gradual disintegration of the Egyptian state. Civil conflict was already evident around the beginning of his reign when High Priest of Amon, Amenhotep, was ousted from office by the king with the aid of Nubian soldiers under command of Pinehesy, Viceroy of Nubia, for overstepping his authority with Ramesses XI. Tomb robbing was prevalent all over Thebes as Egypt's fortunes declined and her Asiatic empire was lost.

As the chaos and insecurity continued, Ramesses was forced to inaugurate a triumvirate in his Regnal Year 19, with the High Priest of Amun Herihor ruling Thebes and Upper Egypt and Smendes controlling Lower Egypt. Herihor had risen from the ranks of the Egyptian military to restore a degree of order, and became the new high Priest of Amun. This period was officially called the Era of the Renaissance or Whm Mswt by Egyptians. Herihor amassed power and titles at the expense of Pinehesy, Viceroy of Nubia, whom he had expelled from Thebes. This rivalry soon developed into full-fledged civil war under Herihor's successor. At Thebes, Herihor usurped royal power without actually deposing Ramesses, and he effectively became the defacto ruler of Upper Egypt because his authority superseded the king's.

Herihor died around Year 6 of the Whm Mswt (Year 24 of Ramesses XI) and was succeeded as High Priest by Piankh. Piankh initiated one or two unsuccessful campaigns into Nubia to wrest control of this gold-producing region from Pinehesy's hands, but his efforts were ultimately fruitless as Nubia slipped permanently out of Egypt's grasp. This watershed event worsened Egypt's woes, because she had now lost control of all her imperial possessions and was denied access to a regular supply of Nubian gold.

Ramesses XI's reign is notable for a large number of important papyri that have been uncovered, including the Adoption Papyrus, which mentions Regnal Years 1 and 18 of his reign; the Turin Taxation Papyrus; the House-list Papyrus; and an entire series of Late Ramesside Letters written by the scribes Dhutmose, Butehamun, and the High Priest Piankh - the latter of which chronicle the severe decline of the king's power even in the eyes of his own officials. Late Ramesside Letter 9 establishes that the Whm Mswt period lasted into a 10th Year (which equates into Year 28 proper of Ramesses XI).

Ad Thijs, in a GM 173 paper, notes that the House-list Papyrus, which is anonymously dated to Year 12 of Ramesses XI (i.e., the document was compiled in either Year 12 of the pre-Renaissance period or during the Whm Mswt era itself), mentions two officials: the Chief Doorkeeper Pnufer, and the Chief Warehouseman Dhutemhab. These individuals were recorded as only ordinary Doorkeeper and Warehouseman in Papyri BM 10403 and BM 10052 respectively, which are explicitly dated to Year 1 and 2 of the Whm Mswt period.

This would suggest that the Year 12 House-list Papyrus postdates these two documents and was created in Year 12 of the Whm Mswt era instead (or Regnal Year 30 proper of Ramesses XI), which would account for these two individuals' promotions. Thijs then proceeds to use several anonymous Year 14 and 15 dates in another papyrus, BM 9997, to argue that Ramesses XI lived at least into his 32nd and 33rd Regnal Years (or Years 14 and 15 of the Whm Mswt). This document mentions a certain Sermont, who was only titled an Ordinary Medjay (Nubian) in the Year 12 House-list Papyrus but is called "Chief of the Medjay" in Papyrus BM 9997. Sermont's promotion would thus mean that BM 9997 postdates the House-list Papyrus and must be placed late in the Renaissance period.

If true, then Ramesses XI should have survived into his 33rd Regnal Year or Year 15 of the Whm Mswt era before dying. Unfortunately, however, it must be stressed that there are clear inconsistencies in the description of an individual's precise title even within the same source document itself. For instance, Papyrus Mayer A mentions both a certain Dhuthope, a doorkeeper of the temple of Amun as well as a Dhuthope, Chief Doorkeeper of the temple of Amun.

The reference to the first Dhuthope occurs in the regular papyrus entry while the other appears towards the end of the list but few people would dispute that they refer to the same man. Similarly, the Necropolis Journal entry from Year 17 of Ramesses XI lists the Chief Workman Nekhemmut as well as a certain workman named Nekhemmut, son of Amenua. While they appear to be the same person--at first glance--their official titles are different with the latter lacking the senior title 'Chief'.

Closer inspection reveals that the latter was actually named as one of eight prisoners in another document while the Chief workman Nekhemmut was noted to be serving in office in Year 17 of Ramesses XI and hardly a prisoner. Hence, Thijs' case for a Year 33 proper for Ramesses XI should be treated with caution. Since there are two attested promotions of individuals in 2 separate papyri, however, there is a small possibility that Ramesses XI did live into his 33rd Regnal Year.

Against this view is the fact that no evidence survives of any Heb Sed Feasts for Ramesses XI. At present, only Thijs' proposal that Papyrus BM 10054 dates to Year 10 of the Whm-Mswt (or Year 28 proper of Ramesses XI) has been confirmed by other scholars such as Von Beckerath and Annie Gasse - the latter in a JEA 87 (2001) paper which studied several newly discovered fragments belonging to this document.

Consequently, it would appear that Ramesses XI's highest undisputed date is presently Year 11 of the Whm-Mswt (or Year 29 proper) of his reign, when Piankh's Nubian campaign terminated which means that the pharaoh had a minimum reign of 29 years when he died - which can perhaps be extended to 30 years due to the "gap between the beginning of Dynasty 21 and the reign of Ramesses XI." with 33 years being hypothethical. Krauss and Warburton specifically write that due to the existence of this time gap,

"Egyptologists generally concede that his reign could have ended 1 or 2 years later than year 10 of the wehem mesut era = regnal year 28."

This also fits in well with Kenneth Kitchen's recently published suggestion that Late Ramesside Letter 41 (not 62) (Wente, 75f; cf 15) with reference to West Theban graffito No.1393 likely shows that the Whm-Mswt era reached into a Year 12 (or Year 30 proper of Ramesses XI.)

When Ramesses XI died, the village of Deir El Medina was abandoned because the Royal Necropolis was shifted northward to Tanis. There was no further need for their services at Thebes.

Sometime during this troubled period, Ramesses XI died in obscurity. While he had a tomb prepared for himself in the Valley of the Kings (KV4), it was left unfinished and only partly decorated since Ramesses XI instead arranged to have himself buried away from Thebes, possibly near Memphis. This pharaoh's tomb, however, includes some unusual features, including four rectangular, rather than square, pillars in its burial chamber and an extremely deep central burial shaft- at over 30 feet or 10 metres long - which was perhaps designed as an additional security device to prevent tomb robbery.

Ramesses XI's tomb was used as a workshop for processing funerary materials from the burials of Hatshepsut, Thutmose III and perhaps Thutmose I during the 21st dynasty under the reign of the High Priest of Thebes, Pinedjem I. Ramesses XI's tomb has stood open since antiquity and was used as a dwelling by the Copts.

Since Ramesses XI had himself buried in Lower Egypt, Smendes rose to the kingship of Egypt, based on the well known custom that he who buried the king inherited the throne. Since Smendes buried Ramesses XI, he could legally assume the crown of Egypt and inaugurate the 21st Dynasty from his hometown at Tanis, even if he did not control Middle and Upper Egypt, which were now effectively in the hands of the High Priests of Amun at Thebes.