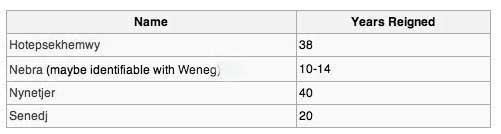

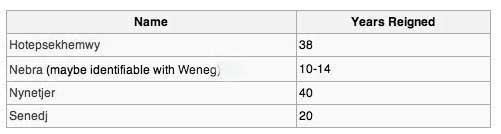

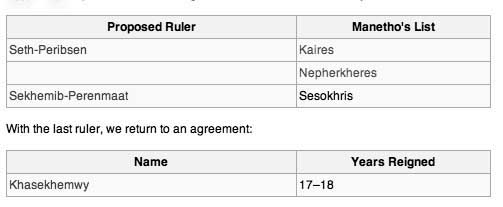

The second dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty II) is often combined with Dynasty I under the group title Early Dynastic Period. It dates approximately from 2890 to 2686 BC. The capital at that time was Thinis. The names of the actual rulers of Dynasty II are in dispute. For the first five pharaohs, the sources are fairly close in agreement. Known rulers, in the History of Egypt, for Dynasty II are as follows:

However, the identity of the next two or three rulers is unclear: we may have both the Horus-name or Nebty (meaning two ladies) -name and their birth names for these rulers; they may be entirely different individuals; or they may be legendary names. On the left are the rulers most Egyptologists place here; on the right are the names that ultimately come from Manetho's Aegyptica.

'Pleasing in Powers'

Hotepsekhemwy (also known as Boethos and Bedjau) is the Horus name of an early Egyptian king who was the founder of the 2nd dynasty. The exact length of his reign is not known; the Turin canon suggests an improbable 95 years while the ancient Greek Historian Manetho reports that the reign of "Boethos" lasted for 38 years. Egyptologists consider both statements to be misinterpretations or exaggerations. They credit Hotepsekhemwy with either a 25 or a 29 year rule.

Hotepsekhemwy's name has been identified by archaeologists at Sakkara, Giza, Badari and Abydos from clay seal impressions, stone vessels and bone cylinders. Several stone vessel inscriptions mention Hotepsekhemwy along with the name of his successor Raneb.

The Horus name of Hotepsekhemwy is the subject of particular interest to Egyptologists and historians, as it may hint at the turbulent politics of the time. The Egyptian word "Hotep" means "peaceful" and "to be pleased" though it can also mean "conciliation" or "to be reconciled", too. So Hotepsekhemwy's full name may be read as "the two powers are reconciled" or "pleasing in powers", which suggests a significant political meaning. In this sense, "the two powers" could be a reference to Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt as well as to the major deities Horus and Seth.

From the reign of Hotepsekhemwy onward it becomes tradition to write horusname and nebtyname in the same way. It is thought that some kind of philosophic background effected that choice, since the horusname reveals a clearly defined, symbolic meaning in its translation (see above). To write horus- and nebtyname in same ways might also point out, that the horusname was adopted after the throne ascending.

Hotepsekhemwy is commonly identified with the Ramesside cartouche names Bedjau from the Abydos king list, Bedjatau from Giza, Netjer-Bau from the Sakkara king list and the name Bau-hetepju from the royal canon of Turin. Egyptologist Wolfgang Helck points to the similar name Bedjatau, which appears in a short king list found on a writing board from the mastaba tomb G1001 of the high official Mesdjeru. "Bedjatau" means "the foundryman" and is thought to be a misreading of the name "Hotepsekhemwy", since the hieroglyphic signs used to write "Hotep" in its full form are very similar to the signs of a pottery kiln and a chick in hieratic writings. The signs of two Sekhem-sceptres were misread as a leg and a drill. A similar phenomenon might have occurred in the case of King Khasekhemwy, where the two sceptres in the horusname were misread as two leg-symbols or two drill-signs. The Abydos king list imitates this Old Kingdom name form of "Bedjatau". The names "Netjerbau" and "Bau-hetepju" are problematic, since Egyptologists can't find any name source from Hotepsekhemwy's time that could have been used to form them.

Little is known about Hotepsekhemwy's reign. Contemporary sources show that he may have gained the throne after a period of political strife, including ephemeral rulers such as Horus "Bird" and Sneferka (the latter is also thought to be an alternate name used by king Qaa for a short time). As evidence of this, Egyptologists Wolfgang Helck, Dietrich Wildung and George Reisner point to the tomb of king Qaa, which was plundered at the end of 1st dynasty and was restored during the reign of Hotepsekhemwy. The plundering of the cemetery and the unusually conciliatory meaning of the name Hotepsekhemwy may be clues of a dynastic struggle. Additionally, Helck assumes that the kings Sneferka and Horus "Bird" were omitted from later king lists because their struggles for the Egyptian throne were factors in the collapse of the first dynasty.

Seal impressions provide evidence of a new royal residence called "Horus the shining star" that was constructed by Hotepsekhemwy. He also built a temple near Buto for the little-known deity Netjer-Achty and founded the "Chapel of the White Crown". The white crown is a symbol of Upper Egypt. This is thought to be another clue to the origin of Hotepsekhemwy's dynasty, indicating a likely source of political power. Egyptologists such as Nabil Swelim point out that there is no inscription from Hotepsekhemwy's reign mentioning a Sed festival, indicating the ruler cannot have ruled longer than 30 years (the Sed festival was celebrated as the anniversary marking a reign of 30 years).

The ancient Greek Manetho called Hotepsekhemwy Boethos (apparently altered from the name Bedjau) and reported that during this ruler's reign "a chasm opened near Bubastis and many perished". Although Manetho wrote in the 3rd century BC - over two millennia after the king's actual reign - some Egyptologists think it possible that this anecdote may have been based on fact, since the region near Bubastis is known to be seismically active.

The location of Hotepsekhemwy's tomb is unknown. Egyptologists such as Flinders Petrie, Alessandre Barsanti and Toby Wilkinson believe it could be the giant underground Gallery Tomb B beneath the funeral passage of the Unas-necropolis at Sakkara. Many seal impressions of king Hotepsekhemwy have been found in these galleries. Egyptologists such as Wolfgang Helck and Peter Munro are not convinced and think that Gallery Tomb B is instead the burial site of king Raneb, as several seal impressions of this ruler were also found there.

Almost all Egyptologists firmly believe that a king by the name of Raneb (or Nebra) succeeded the first king of Egypt's 2nd Dynasty, Hotepsekhemwy. There is little information about Raneb, his reign is important to us because of its chronological position during the Egyptian empire's formative years. Presumably, Raneb was Hotepsekhemwy's son, or perhaps his brother, but there is little evidence to prove such. Raneb, which was probably this king's birth name, means "Re is the Lord", but many believe, because there seems to have been no specific mention of the god Re prior to this time, that it should more appropriately be read as Nebra, meaning "Lord of the Sun". There is evidence from later King lists that his birth name was probably Kakaw (or Kakau).

Manetho, the great historian of ancient Egypt, believed that Raneb reigned for some 39 years. However, many modern scholars believe that his reign was much shorter, lasting between ten and nineteen years years. In fact, some scholars seem to believe that Raneb's reign and that of his predecessor, Hotepsekhemwy, should together be 38 or 39 years, with both therefore having shorter reigns then provided by Manetho.

His reign is attested to by various sources, including finding from the enormous middle Saqqara tomb A (cylinder seal impressions) south of Djoser's temenos south wall and the inscription on a statuette of Redjit.

There are references to Nebra on a Memphite stela now located in the Metropolitan Museum, a statuette, and a rock graffiti near Armant in the western desert (and possibly another at site 40 in the Eastern Desert), close to an ancient trade route linking the Nile with the western Oasis.

Manetho also tells us that Raneb introduced the worship not only of the sacred goat of Mendes, but also of the sacred bull of Mnevis at the old sun-worship center of Heliopolis, and the Apis bull at Memphis. However, scholars now appear to believe that the cult of the Apis bull was established by a former king, which is attested on a stele dating from the rule of Den (Udimu). Irregardless, it would seem that his name, whether stated as Raneb or Nebra, indicates a significant shift of worship to the sun god, which would have a very important impact on much of Egypt's remaining history.

Apparently at the end of the 1st Dynasty, there was considerable rebellion, presumably problems held over from the empires initial unification. We are told that Hotepsekhemwy reunited the two lands of Northern (Lower) and Southern (Upper) Egypt, so if follows that Raneb perhaps ruled during a period of a tentative peace. We are not certain of his burial place. 1st Dynasty kings appear to have mostly been buried at Abydos, but his seal impressions at Saqqara suggest that he could have been buried there, though there is absolutely no certainty on that matter. Regardless, future excavation may eventually reveal more to us on this interesting and important era of early Egyptian history and this relatively unknown king.

Raneb was succeeded by Ninetjer (Nynetjer), though once again, we have no real information on this latter king's relationship to Raneb.

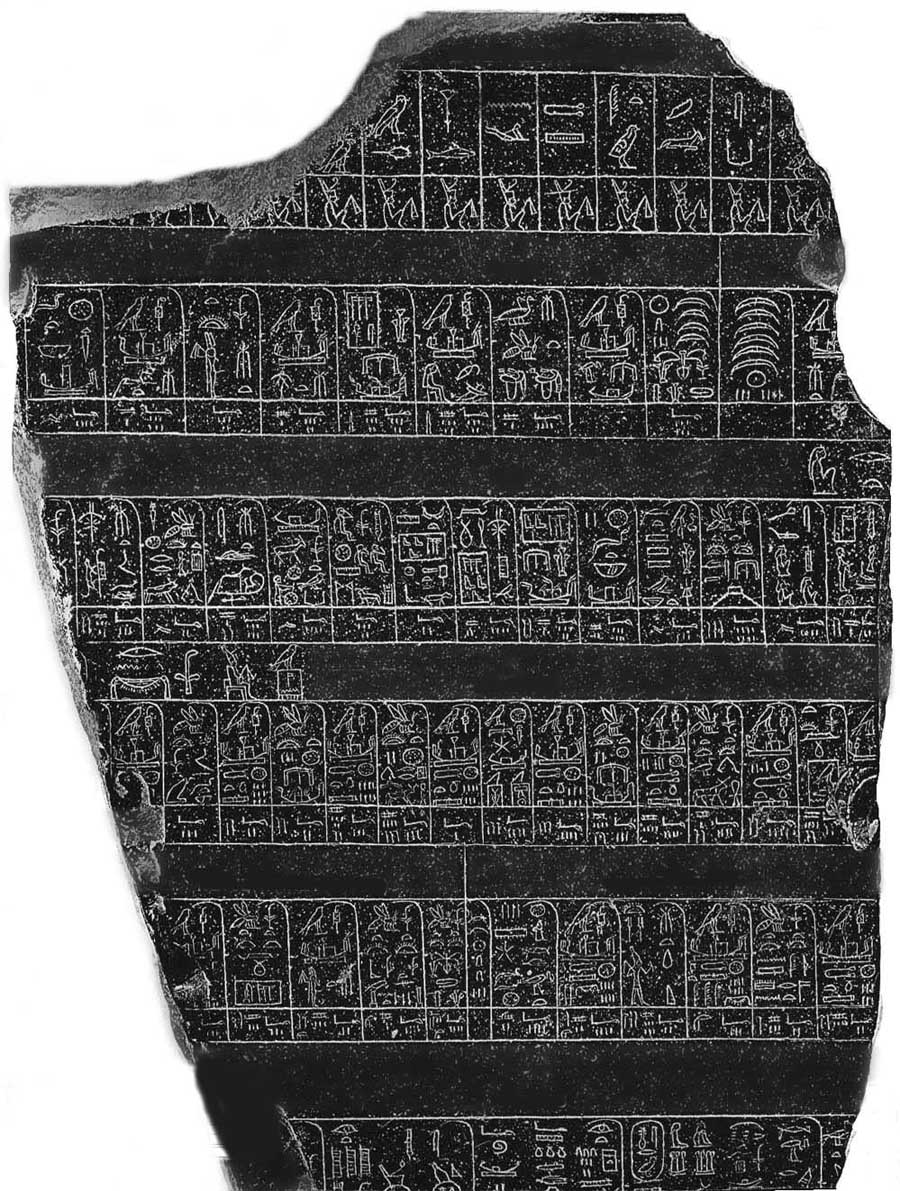

Ninetjer was the third king of the 2nd Dynasty. Memphis was his capitol. Ninetjer is actually by far the best attested king of the early 2nd Dynasty. Given the position of his titulary on the Palermo Stone, he must have ruled Egypt for at least thirty-five years, though Manetho gives him forty-seven. In fact, most of what we know of this king is derived from the annals recorded on the Palermo Stone, where the whole fourth register records events between his fifth or sixth year through his twentieth or twenty-first. However, the king is also evidenced by three fine tombs in the elite cemetery at North Saqqara containing sealings of Ninetjer, as well as one across the Nile in the Early Dynastic necropolis at Helwan. There were additionally five different jar-sealings of the king discovered in a large mastaba near Giza. However, more sealings of Ninetjer eventually led to the identification of the king's own tomb at Saqqara (though some scholars doubt that this is clearly his tomb).

From the Palermo Stone, we learn of the foundation of a chapel or estate named Hr-rn during the king's seventh year on the throne. Otherwise, most of the events evidenced on that record are regular ritual appearances of the king and various religious festivals. A festival of Sokar apparently was held every six years during his reign, and the running of the Apis bull was recorded twice during years nine and fifteen of his reign.

Most of the festivals recorded during his reign were held in the region of Memphis, with the exception of a ceremony associated with the goddess Nekhbet of Elkab during year nineteen. The fact that most activity associated with this king occurred in the region of Memphis may be important. Little evidence of the king is found outside of this region and it may be that his activities was largely, if not completely confined to Lower Egypt. Towards the end of his reign, there was a good deal of internal tension in Egypt, perhaps even civil war.

The Palermo Stone tantalizes us with the possibility of this beginning in Ninetjer's thirteenth year. It records the attack of several towns including one who's name means "north land" or "House of the North" (the other city was Shem-Re). Some have interpreted this entry in the Palermo Stone to mean that Ninetjer had to suppress a rebellion in Lower, or Northern Egypt.

Unfortunately, the Palermo Stone ends with the nineteenth year of his reign. However, inscriptions on stone vessels, which probably date to the latter part of his reign, appear to record several other events, such as a four occurrence of the Sokar Festival, which probably took place in year twenty-four, and the "seventeenth occasion of the [biennial] census", which may have occurred in his thirty-fourth year on the throne.

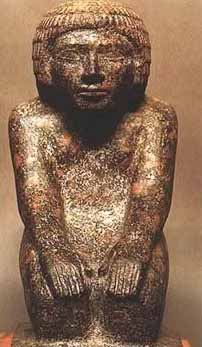

Other than the various inscribed stone vessels, only two other artifacts have been unearthed that bear the king's name. One of these is a small ivory vessel from the Saqqara area, but the other is a small statue of considerable significance, both to the king's history and especially Egyptian art. The statuette is made of alabaster, depicting the king on his throne and wearing the close fitting robe associated with the Sed-festival. Upon his head rests the White Crown of Lower Egypt. This crude stone statuette of unknown provenance, now in the Georges Michailides Collection, represents the earliest complete and identifiable example of three-dimensional royal statuary from Egypt.

It also provides evidence that the king celebrated at least one Sed-festival, which would have been likely given the apparent long reign of Ninetjer. While no contemporary inscriptions evidence this celebration, there was also a stock of stone vessels discovered in the Step Pyramid galleries that may have been prepared for this event. Some scholars theorize that this further evidences the difficulties late in the king's reign, suggesting that these were never distributed due to domestic unrest which disrupted communications and weakened the authority of the central administration. Hence, the stone vessels were later appropriated by subsequent kings of the late 2nd and early 3rd Dynasties.

The name of Ninetjer's successor to the throne, Peribsen (Seth-Peribsen), unusually referencing the god Seth, is another piece of evidence indicating unrest. However, it is likely that Peribsen did not directly replace Ninetjer. It is likely that as many as two or more shadowy rulers (Weneg, Sened and Nubnefer) took the throne of perhaps a divided Egypt in the interim. However, most modern kings' lists do not reference all of them, and some list only one or two.

Weneg (or Uneg), also written as Weneg-Nebti, is the Nebti name of an early Egyptian king, who ruled during the second dynasty. Although his chronological position is clear to Egyptologists, it is unclear for how long King Weneg ruled. It is also unclear as to which of the archaeologically identified Horus-kings corresponds to Weneg.

The name Weneg is generally accepted to be a nebti-name, introduced by the crest of the "Two Ladies", the goddesses Nekhbet and Wadjet. Weneg's name appears in black ink inscriptions on alabaster fragments and in inscriptions on schist-vessels. Seventeen vessels bearing his name have been preserved; eleven of them were found in the underground galleries beneath the step pyramid of king Djoser at Sakkara. Egyptologists such as Wolfgang Helck and Francesco Raffaele point out that all the inscriptions are made in the place of existing inscriptions, which means that the names that were originally placed on the vessels were completely different.

The symbol that was used to write Weneg's name is the object of significant dispute between egyptologists to this day. The so-called "weneg flower" is rarely used in Egyptian writing. Mysteriously, the weneg flower is often guided by six vertical "strokes", three of them on each side of the flower bud. The meaning of these strokes is unknown. After Weneg's death, his heraldic flower was not used again until king Teti (6th dynasty), when it was used in his pyramid texts to name a deity which was described as "beloved of Ra" and as the "deputy of the deceased king". So it seems that the weneg flower was somehow connected with the Egyptian sun cult. But the true meaning of the flower as a king's name remains unknown.

Since Weneg's name first became known to Egyptologists, scholars have been trying to match the nebti name of Weneg to contemporary Horus-kings. The following sections discuss some of the theories.

Egyptologist Jochem Kahl argues that Weneg was the same person as king Raneb, the second ruler of the 2nd dynasty. He points to a vessel fragment made from an igneous material, which was found in the tomb of king Peribsen (a later ruler of 2nd dynasty) at Abydos. He believed he had found on the pot sherd weak, but clear, traces of the weneg-flower beneath the inscribed name of king Ninetjer.

On the right side of Ninetjer's name the depiction of the Ka house of king Raneb is partially preserved. The complete arrangement led Kahl to the conclusion that the weneg flower and Raneb's name were connected to each other and king Ninetjer later replaced the inscription. Kahl also points out that king Ninetjer wrote his name mirrored, so that his name points in the opposite direction to Raneb's name. Kahl's theory is the subject of continuing debate since the vessel inscription is badly damaged and thus leaves plenty of room for varying interpretations.

Egyptologists such as Nicolas Grimal, Wolfgang Helck and Walter Bryan Emery identify Weneg with king Sekhemib-Perenmaat and with the Ramesside royal cartouche-name Wadjenes. Their theory is based on the assumption that Sekhemib and Seth-Peribsen were different rulers and that both were the immediate successors of king Ninetjer. But this theory is not commonly accepted, because clay seals of Sekhemib were found in the tomb of king Khasekhemwy, the last ruler of 2nd dynasty. The clay seals set Sekhemib's reign close to Khasekhemwy's, whilst the Ramesside name "Wadjenes" is placed near the beginning of 2nd dynasty.

Egyptologists such as Peter Kaplony and Richard Weill argue that Weneg was a separate king from other kings of the period. They suggest that Weneg succeeded Ninetjer and his name is preserved in Ramesside kinglists under the name "Wadjenes". Their assumption is firstly based on the widely accepted theory that Ramesside scribes interchanged the weneg-flower with the papyrus haulm, changing it into the name "Wadjenes".

Secondly, Kaplony and Weill's theory is based on the inscription on the Cairo stone. They believe that the name "Wenegsekhemwy" is preserved over the third line of year events. This theory is also not widely accepted, as the Cairo stone is badly damaged and the very weak traces of the hieroglyphs leave too much room for different interpretations.

Little is known about Weneg's reign. The vessel inscriptions mentioning his name only show reports about ceremonial events, such as the "raising up of the pillars of Horus". This feast is frequently reported on vessels from Ninetjer's reign, which brings Weneg's chronological position very close to that of Ninetjer.

The length of Weneg's rulership is unknown. If he was the same person as king Wadjenes, he ruled (according to the Royal Canon of Turin) for 54 years. If Weneg was same person as king "Tlas", mentioned by the historian Manetho, he ruled for 17 years. But modern Egyptologists have doubts about both statements and evaluate them as misinterpretations or exaggerations. If Weneg was actually a separate ruler, as Richard Weill and Peter Kaplony believe, he may have ruled for 12 years, depending on their reconstructions of the Cairo stone inscriptions.

One theory suggests that the once unified kingdom of Egypt was divided after Ninetjer's death into two parts. Consequently, for a period after king Weneg's death, two kings ruled at the same time over Egypt suggesting that Weneg was an independent ruler. This assumption is based on the observation that both the Thinite and Memphite king lists of the Ramesside era mention the names "Wadjenes" and "Sened" as the immediate successors of king Ninetjer. The Abydos king lists, for example, mention only six kings for the 2nd dynasty, whilst all the other kinglists mention nine kings. So Weneg may have been the last king who had ruled over the whole of Egypt, before sharing his throne (and control over Egypt) with another king. It remains unclear who the other king may have been.

Senedj is the name of an early Egyptian king (pharaoh) who may have ruled during the 2nd dynasty. His historical standing remains uncertain, as there are no contemporary records about Senedj. The earliest mention of his name appears during the 4th dynasty. The exact duration of Senedj's reign is unknown. The Turin Canon credits him with a reign of 70 years, the ancient Greek historian Manetho suggests a reign of 41 years. Egyptologists question both statements and consider them to be misinterpretations or exaggerations.

The earliest source referring to king Senedj dates back to the beginning or middle of the 4th dynasty. The name, written in a cartouche, appears in the inscription on a false door belonging to the mastaba tomb of the high priest Shery at Sakkara. Shery held the title overseer of all wab-priests of king Peribsen in the necropolis of king Senedj, "Great one of the ten of Upper Egypt" and "god's servant of Senedj". Senedj's name is written in archaic form and set in a cartouche, which is an anachronism, since the cartouche itself was not used until the end of 3rd dynasty under king Huni.

The coffin of a unknown royal female, dating to the beginning of the 18th dynasty, is a further name source. The coffin inscription lists several kings' names, beginning with king Senedj, followed by a destroyed name. Then the list continues with Antef, Mentuhotep II, Senusret II, Senusret III, Sekhaenre and Ahmose I. The coffin was found by Luigi Vassalli in tomb T100.2 at Dra' Abu el-Naga'.

Senedj's name is included in the kinglists of the ramesside era, although it is written in different ways. While the kinglist of Abydos imitates the archaic form, the royal canon of Turin and the kinglist of Sakkara form the name with the hieroglyphic sign of a plucked goose.

The latest mention of Senedj's name appears on a small bronze statuette in the shape of a kneeling king wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt and holding incense burners in its hands. Additionally the figurine wears a belt which has Senedj's name carved at the back.

Egyptologist Peter Munro has written a report about the existence of a mud seal inscription showing the cartouche name Nefer-senedj-Ra, which he thinks to be a version of Senedj, but neither the seal nor its inscription ever were published. Therefore the authenticity of this finding is questionable.

The horus name of Senedj remains unknown. The false door inscription of Shery might indicate that Senedj is identical with king Seth-Peribsen and that the name "Senedj" was brought into the kinglists, because a seth-name was not allowed to be mentioned. Other Egyptologists, such as Wolfgang Helck and Dietrich Wildung, are not so sure and believe that Senedj and Peribsen were different rulers. They point out that the false door inscription has the names of both strictly separated from each other. Additionally Wildung thinks that Senedj donated an offering chapel to Peribsen in his necropolis. This theory is questioned by Helck and Hermann A. Schlogl, who point to the clay seals of king Sekhemib found in the entrance area of Peribsen's tomb, which might prove that Sekhemib buried Peribsen, not Senedj.

Egyptologists such as Wolfgang Helck, Nicolas Grimal, Hermann Alexander Schlogl and Francesco Tiradritti believe that king Ninetjer, the third ruler of 2nd dynasty, left a realm that was suffering from an overly complex state administration and that Ninetjer decided to split Egypt to leave it to his two sons (or, at least, two chosen successors) who would rule two separate kingdoms, in the hope that the two rulers could better administer the states.

In contrast, Egyptologists such as Barbara Bell believe that a economic catastrophe such as a famine or a long lasting drought affected Egypt. Therefore, to better address the problem of feeding the Egyptian population, Ninetjer split the realm into two and his successors founded two independent realms, until the famine came to an end. Bell points to the inscriptions of the Palermo stone, where, in her opinion, the records of the annual Nile floods show constantly low levels during this period.

Bell's theory is refuted today by Egyptologists such as Stephan Seidlmayer, who corrected Bell's calculations. Seidlmayer has shown that the annual Nile floods were at usual levels at Ninetjer's time up to the period of the Old Kingdom. Bell had overlooked that the heights of the Nile floods in the Palermo stone inscription only takes into account the measurements of the nilometers around Memphis, but not elsewhere along the river. Any long-lasting drought can therefore be excluded.

It is also unclear, if Senedj already shared his throne with another ruler, or if the Egyptian state was split at the time of his death. All known kinglists such as the Sakkara list, the Turin canon and the Abydos table list a king Wadjenes as predecessor of Senedj.

After Senedj, the kinglists differ from each other in respect of the successors. While the Sakkara list and the Turin canon mention the kings Neferka(ra), Neferkasokar and Hudjefa I as immediate successors, the Abydos list skips them and lists a king Djadjay (identical with king Khasekhemwy). If Egypt was already divided when Senedj gained the throne, kings like Sekhemib and Peribsen would have ruled Upper Egypt, whilst Senedj and his successors, Neferka(ra) and Hudjefa I, would have ruled Lower Egypt. The division of Egypt was brought to an end by king Khasekhemwy.

It is unknown where Senedj was buried. Toby A. Wilkinson assumes that the king might have been buried at Sakkara. To support this view, Wilkinson makes the observation that mortuary priests in earlier times were never buried too far away from the king for whom they had practised the mortuary cult. Wilkinson thinks that one of the Great Southern Galleries within the Necropolis of King Djoser (3rd dynasty) was originally Senedj's tomb.[20

Peribsen (also known as Seth-Peribsen and Ash-Peribsen) is the serekh name of an early Egyptian king who ruled during the 2nd dynasty. Unlike many other pharaohs of this dynasty, Peribsen is well-attested in the archaeological records. Peribsen's royal name is a subject of interest for Egyptologists and historians alike as it differs from the traditional practice with its connection to the deity Seth instead of Horus. This is still the subject of debate and investigations as to why Peribsen chose this name. The details of Peribsen's life remain obscure and the duration of his reign is unknown.

Peribsen's serekh name was found pressed on earthen jar seals made of clay and mud and in inscriptions on vessels made of alabaster, sandstone, porphyry and black schist. The seals and vessels were found in Peribsen's tomb and at Elephantine.

Also two large tomb stelae made of dark grey granite were found at his burial site. Their shape is unusual, because it makes them look unfinished and rough. Egyptologists suspect that this was done deliberately, but the meaning behind this is unknown. A cylinder seal of unknown provenance shows Peribsen's name inside a cartouche and gives the epithet Merj-netjeru (beloved of the gods). This arrangement leads Egyptologists and archaeologists to the conclusion that the seal must be of a much later date, because the royal cartouche was not yet in use during Peribsen's lifetime. Another seal of the same material shows Peribsen's name without a cartouche and with the royal title Nisut-Bity ("king of Lower- and Upper Egypt").

Peribsen's name is unusual because it was an Egyptian tradition that a king had to choose the falcon-shaped deity Horus as his royal patron. This is clearly expressed in one of the king's names, the Horus name. The falcon of the god Horus was placed at the top of the image of the royal palace facade (serekh) to show the king's religious allegiance. The actual name of the king was written within the upper part of the palace facade.

However, Peribsen did not choose the traditional royal protector Horus, but instead chose the deity Seth, who was also popular in early dynasties, but became unpopular during the First Intermediate Period. Many later rulers, especially during the New Kingdom and Late Period, condemned Seth and any royal ancestor who had connected his name with that deity. Instead, some pharaohs did the same as Peribsen and connected their birth names to Seth. Examples include the (13th dynasty) pharaoh Sutekh, the (19th dynasty) ruler Seti I and the (20th dynasty) king Setnakhte.

Since Peribsen is known for his unusual name, Egyptologists and historians have sought to understand the possible motivations that made Peribsen change his name. The following sections discuss some of these theories.

An old theory, supported by Egyptologists such as Percy Newberry and Jaroslav Cerny once held that Peribsen was a heretic who sought to introduce a new form of state religion to Egypt, similar to the actions of a much later (18th dynasty) pharaoh, Akhenaten, who had required Egyptians to serve only one god (in his case the sun-god Aten). Newberry proclaims that the priest castes fought each other just 'like in the Manner of a war of the roses'.

The theory of a "heretic Peribsen" was based on the observation that the name Peribsen was excluded from later king lists and that the king's tomb was destroyed and plundered. Furthermore the tomb stelae of Peribsen, which once clearly showed the Seth animal, were badly scratched with the aim of removing any trace of the animal. This was seen as the actions of religious opponents to the sethian priest-caste.

Today this theory has little support. Archaeological evidence of Peribsen has only been found in Upper Egypt. His name does not appear in Lower Egyptian records surviving from that time. Therefore, it is argued that Peribsen cannot have ruled over all of Egypt, thus he was not in a position to require all Egyptians to support a new form of state religion.

Another piece of evidence that argues against the theory of heresy is the false door of the priest Shery at Sakkara, who held office during the early 4th dynasty. The inscription on the false door connects the name of Peribsen in one sentence with another king, Senedj. Shery held the title "overseer of all wab-priests of king Peribsen in the necropolis of king Senedj". This implies that a mortuary cult based around king Peribsen was in place at least until the 4th dynasty, which is inconsistent with the idea that Peribsen was considered a heretic.

Seal impressions found in the tomb of Peribsen at Abydos, show several deities such as Ash, Min and Bastet, which were venerated during Peribsen's time as king. This is further evidence against the theory that Peribsen tried to introduce a completely new state religion.

The theory of Newberry, Cerny and Grdseloff was founded on the very limited archaeological information available during their lifetimes. Thus they had difficulty coming up with a more robust explanation for the change in name by Peribsen.

The earlier theories of Newberry, Cerny and Grdseloff also held that the Egyptian state under Peribsen was suffering from several civil wars, which broke out when the king changed his name or were caused by economic problems. These civil wars could have been a reason why later king lists excluded Peribsen's name.

In contrast, more modern theories now hold that the Egyptian kingdom was divided peacefully. Egyptologists such as Michael Rice, Francesco Tiradritti and Wolfgang Helck point to the once palatial and well preserved mastaba tombs at Sakkara and Abydos belonging to high officials such as Ruaben, Nefer-Setech and many others. These are all dated to the reigns of Nynetjer up to Khasekhemwy, the last ruler of 2nd dynasty. Egyptologists consider that the archaeological record of the mastabas' condition and the original architecture as proof that the statewide mortuary cults for kings and noblemen successfully took place during the whole dynasty. This circumstance is also inconsistent with the theory of civil wars and/or economic problems.

It is unclear when exactly the division of the Egyptian state occurred. It might have happened at the beginning of Peribsen's rule or shortly before. Because Peribsen chose the deity Seth as his new throne patron, Egyptologists are of the view that Peribsen was a chieftain from Thinis or a prince of the Thinite royal house. This theory is based on Seth being a deity of Thinite origin, which would explain Peribsen's choice: his name changing may have been nothing more than smart political (and religious) propaganda. Peribsen is thought to have gained the Thinite throne and ruled only Upper Egypt, whilst other rulers held the Memphite throne and ruled Lower Egypt.

Peribsen's identity is also the subject of debate by Egyptologists and historians. Egyptologists such as Walter Bryan Emery, Kathryn A. Bard and Flinders Petrie believe that Peribsen was identical to the king Sekhemib-Perenmaat, a ruler that had connected his name with the falcon-god Horus and who definitely ruled during 2nd dynasty. Emery, Bard and Petrie point to several clay seals that were found in the tomb entrance of Peribsen's necropolis. Sekhemib's tomb has not yet been found.

Egyptologists such as Hermann Alexander Schlogl, Wolfgang Helck, Peter Kaplony and Jochem Kahl instead believe that Peribsen was a different ruler to Sekhemib. They point out that the clay seals were only found at the entrance area of Peribsen's tomb and that none of them ever shows Peribsen and Sekhemib's names together in one inscription. They compare the findings with the ivory tablets of king Hotepsekhemwy found at the entrance of king Qaa's tomb. Therefore Schlogl, Helck, Kaplony and Kahl are convinced that Sekhemib's seals support the view that Sekhemib buried Peribsen.

Egyptologists such as Toby Wilkinson and Helck believe that Peribsen and Sekhemib could have been related. Their theory is based on the stone vessel inscriptions and seal impressions that show strong similarities in their typographical and grammatical writing styles. The vessels of Peribsen for example show the notation "ini-setjet" ("tribute of the people of Sethroe"), whilst Sekhemib's inscriptions have the notation "ini-chasut" ("tribute of the desert nomads"). A further indication that Peribsen and Sekhemib were related is the serekh-name of both, as they both use the syllables "Per" and "ib" in their names.

It is not clear if the Ramesside king lists truly omit Peribsen. The false door inscription of Shery might indicate that Peribsen is identical with king Senedj ("Senedj" means "the frightening") and that this name was used in the king lists, for the seth name was not allowed to be mentioned.

Since archaeological records seem to support the view that the Egyptian state was divided during the reign of king Peribsen, it is the subject of debate by Egyptologists and historians as to why his predecessor Nynetjer decided to split the state.

Egyptologists such as Wolfgang Helck, Nicolas Grimal, Hermann Alexander Schlogl and Francesco Tiradritti believe that king Ninetjer, the third ruler of 2nd dynasty and a predecessor of Peribsen, left a realm that was suffering from an overly complex state administration and that Ninetjer decided to split Egypt to leave it to his two sons (or, at least, two chosen successors) who would rule two separate kingdoms, in the hope that the two rulers could better administer the states.

In contrast, Egyptologists such as Barbara Bell believe that a economic catastrophe such as a famine or a long lasting drought affected Egypt. Therefore, to better address the problem of feeding the Egyptian population, Ninetjer split the realm into two and his successors founded two independent realms, until the famine came to an end. Bell points to the inscriptions of the Palermo stone, where, in her opinion, the records of the annual Nile floods show constantly low levels during this period.

Bell's theory is refuted today by Egyptologists such as Stephan Seidlmayer, who corrected Bell's calculations. Seidlmayer has shown that the annual Nile floods were at usual levels at Ninetjer's time up to the period of the Old Kingdom. Bell had overlooked that the heights of the Nile floods in the Palermo stone inscription only takes into account the measurements of the nilometers around Memphis, but not elsewhere along the river. Any long-lasting drought can therefore be excluded.

Whatever the exact reason for the division of Egypt may have been, there is strong archaeological evidence that Peribsen ruled only in Upper Egypt. His realm extended to the Isle of Elephantine, where he founded a new administrative centre called "The white house of treasury". His new royal residence, called the "protection of Nubty", was founded near Kom Ombo ("nubty" was the Ancient Egyptian name of Naqada).

Inscriptions on stone vessels mention a "ini-setjet" ("tribute of the people of Sethroe"), which might indicate that Peribsen founded a cult centre for the deity Seth in the Delta, but this would assume that Peribsen ruled over the whole of Egypt, or, at least, that he was accepted as king across all of Egypt during his lifetime. Because Peribsen only ruled Upper Egypt, the administrative titles of scribes, seal-bearers and overseers had to be adjusted to the new political situation. For example, titles like "sealer of the king" were changed into "sealer of the king of Upper Egypt".

The administration system from Peribsen and Sekhemib shows a clear and well identified hierarchy; an example: Treasury house -> pension office -> property -> vineyards -> private vineyard. King Khasekhemwy, the last ruler of 2nd dynasty, was able to re-unify the state administration of Egypt and therefore unite the whole of Ancient Egypt. He brought the two treasury houses of Egypt under the control of the "House of the King", bringing them into a new, single administration centre.

One official from Peribsen's reign is known to Egyptologists by his stela: Nefer-Setekh ("Seth is beautiful").

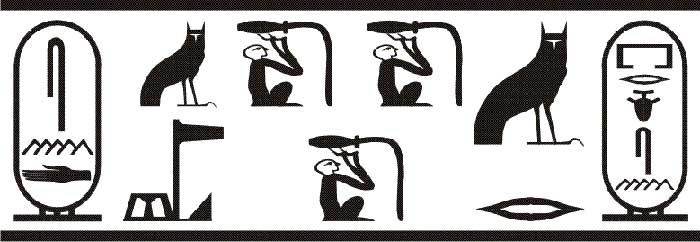

In the tomb of Peribsen at Abydos clay seals were found which show the first complete sentence in Egyptian history. The inscription says: "The golden one/He of Ombos hath unified/handed over the two realms for/to his son, the king of Lower and Upper Egypt, Peribsen". The title "The golden one", also read as "He of Ombos", is considered by Egyptologists to be a religious form of address to the deity Seth.

Egyptologists and historians such as Helck, Tiradritti, Schlogl, Emery and Grimal are convinced that Peribsen had to share his throne with other kings. Since the artifacts surviving from his lifetime show that he and his successor Sekhemib-Perenmaat ruled only in Upper Egypt, it is subject of investigation as to who ruled in Lower Egypt as the corresponding kings.

The Rammesside king lists differ in their order of royal names from king Senedj onward. A reason may be that the royal table of Sakkara and the royal canon of Turin reflect Memphite traditions, which only allowed Memphite rulers to be mentioned. The Abydos king list instead reflects Thinite traditions and therefore only Thinite rulers appear on that list. Until king Senedj, all the king lists accord with each other. After him, the Sakkara list and the Turin list mention three kings as successors: Neferkara I, Neferkasokar and Hudjefa I. The Abydos king list skips these kings and jumps forward to Khasekhemwy, calling him "Djadjay". The discrepancies are considered by Egyptologists to be the result of the division of Egypt during the 2nd dynasty.

A further problem are the Horus names and nebty names of kings used in inscriptions found in the Great Southern Gallery in the necropolis of the (3rd dynasty) king Djoser at Sakkara. Stone vessel inscriptions mention kings such as Nubnefer, Weneg-Nebty, Horus Ba, Horus "Bird" and Za, but each of these kings is mentioned only a few times, which makes Egyptologists think that they did not reign for very long.

King Sneferka might be identical with king Qa'a or an ephemeral successor of his. King Weneg-Nebty might be identical with the Ramesside cartouche name Wadjenes. But kings such as Nubnefer, Bird and Za remain a mystery. They never appear anywhere else but at Sakkara and the number of objects surviving from their lifetimes is very limited. Schlogl, Helck and Peter Kaplony postulate, that Nubnefer, Za and Bird were the corresponding rulers of Peribsen and Sekhemib and ruled in Lower Egypt, whilst the latter two ruled Upper Egypt.

Peribsen was buried in tomb P at the royal cemetery at Umm el-Qa'ab near Abydos. First excavations started in 1898 under the supervision of British archaeologist and Egyptologist Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie. The tomb is of ordinary construction. It measures 16 metres x 13 metres and is quite different to the other tombs in this area. The main burial chamber, measuring 7.3 metres x 2.9 metres, is made of mud bricks and erected as a separate structure in the midst of the tomb.

Between the king's chamber and the outer wall is a surrounding passage. Between entrance and burial chamber is an antechamber which was once divided by a doorway into two sections, each section contained four storage rooms. The tomb was already plundered by tomb robbers during antiquity, but numerous stone vessels and earthen jars from Peribsen's reign were found, some of the stone vessels had copper-coated rims. Vessels from preceding rulers such as Ninetjer and Raneb were also found. Outside the entrance two large tomb stelae were placed (they are now on display in different museums).

Close to Peribsen's tomb a royal funerary enclosure made of mud bricks was found. Clay seals with Peribsen's serekh name on them were found near the eastern entrance and inside a destroyed offering shrine. The findings support the view that the building was part of Peribsen's burial site. The funerary enclosure is today commonly known as "Middle Fort".

First excavations started in 1904 under the supervision of Canadian archaeologist Charles Trick Currelly and British egyptologist Edward Russell Ayrton. The enclosure wall was located at the north-west site of Khasekhemwy's funerary enclosure Shunet El-Zebib (raisin barn).

The one of Peribsen measures 108 metres x 55 metres and contained only a few cult buildings. The enclosure has three entrances: one to the east, one to the south and one to the north. A small shrine, measuring 12.3 metres x 9.5 metres was located at the south-east-corner of the funerary enclosure. It once contained three small chapels. No subsidiary tombs were found.

The tradition of burying the family and court of the king when he died was abandoned at the time of king Qaa, one of the last rulers of the 1st dynasty.

"The Two Powerful Ones Appear"

Khasekhemwy is perhaps the best attested ruler of the 2nd Dynasty, a period that we know very little about in general.

Khasekhemwy (d. 2686 BC; sometimes spelled Khasekhemui) was the 5th and final Pharaoh of the Second dynasty of Egypt, ruling for 30 years. Little is known of Khasekhemwy, other than that he led several significant military campaigns and built several monuments, still extant, mentioning war against the Northerners.

Egyptologists have normally placed him as the successor of Seth-Peribsen, though Manetho lists three kings between them, consisting of Sethenes (Sendji), Chaires (Neterka) and Nebhercheres (Neferkara). However, there is no archaeological evidence for these kings and almost no other information to verify their existence.

However, some Egyptologists believe he had another immediate predecessor named Khasekhem, with an obviously similar name, though other scholars believe Khasekhem and Khasekhemwy were in fact the same person. They argue that Khasekhem changed his name to Khasekhemwy after he squashed a rebellion, thus reuniting Upper and Lower Egypt. His new Horus name means "The Two Powerful Ones appear". Afterwards, the rendering of his name on his serekh was surmounted by both the Horus falcon and Seth jackel, marking it as unique in Egyptian history.

Perhaps Khasekhemwy's use of both the Horus and Seth god's representations in his name was an act of reconciliation. We might even assume a politically inspired unification of the country, were it not for evidence to the contrary. He in fact is believed to have married a northern princess, but apparently only to cement the control he gained through battle.

On a stone vase, we find recorded, "The year of fighting the northern enemy within the city of Nekhet." Nekhet, now known as el-Kab, lies on the eastern bank of the Nile across from the ancient capital, Nekhen, known to the Greeks as Hierakonpolis. Hence, this was a major and dramatic battle between Upper and Lower Egyptians. On the base of two seated statues of Khasekhemwy, we are told that some 47,209 northerners were killed, a huge number considering the relatively small population of Egypt during the early dynastic period.

The Northern princess that Khasekhemwy married, a woman named Nemathap (Nimaatapis), who jar sealings reveal as "The King-bearing Mother". She probably mothered the earliest rulers of Egypt's 3rd Dynasty including Djoser.

It is also important to note that the earliest inscriptional evidence of an Egyptian king at the Lebanese site of Byblos belonged to the reign of Khasekhemwy.

Khasekhemwy apparently undertook considerable building projects upon the reunification of Egypt. He built in stone at el-Kab, Hierakonpolis and Abydos. He apparently built a unique, as well as huge tomb at Abydos, the last such royal tomb built in that necropolis (Tomb V). The trapezoidal tomb measures some 70 meters (230 ft) in length and is 17 meters (56 ft) wide at its northern end, and 10 meters (33 ft) wide at its southern end. This area was divided into 58 rooms.

Prior to some recent discoveries from the First Dynasty, its central burial chamber was considered the oldest masonry structure in the world, being built of quarried limestone. Here, the excavators discovered the king's scepter of gold and sard, as well as several beautifully made small stone pots with gold leaf lid coverings, apparently missed by earlier tomb robbers. In fact, Petrie detailed a number of items removed during the excavations of Amelineau. Other items included flint tools, as well as a variety of copper tools and vessels, stone vessels and pottery vessels filled with grain and fruit. There were also small, glazed objects, carnelian beads, model tools, basketwork and a large quantity of seals.

However, probably more impressive is a structure located in the desert about 1,000 yards from the tomb. Known as the Shunet el-Zebib (storehouse of the Dates), it was a huge rectangular structure measuring 123 x 64 meters (404 x 210 ft). The mudbrick walls of the structure, with their articulated palace facade, were as much as 5 meters (16 ft) thick and as high as 20 meters (66 ft). Incredibly, fragments of these mudbrick walls have survived for nearly 5,000 years.

Some Egyptologists believe that the complex of buildings within this enclosure may have functioned in a capacity similar to a mortuary temple. In fact, it had much in common with the enclosure of Djoser's Step Pyramid at Saqqara. Besides the niched inner walls of the parameter, a large mound of sand and gravel covered with mud brick, approximately square in plan, was discovered within the enclosure. Located in a similar position within the enclosure as the Step Pyramid in Djoser's complex, this mound may have been a forerunner of the step pyramids.

Khasekhemwy's structures are seen as an important evolutionary stage of the ancient Egyptian mortuary complex. Khasekhemwy died in about 2686 BC.

References: