Depression can be clinical (genetic) or based on life experiences. Clinical depression will come and go in one's lifetime. As one ages they learn to cope with depression often changing treatment and therapists.

People approach depression in many ways sometimes taking antidepressants often combined with holistic remedies. Yoga and other forms of physical activity and meditation can help with anxiety and related disorders.

Electroconvulsive therapy (shock treatments) are having positive affects for many people but feel risky. It's all about trial and error to find what works and what doesn't. Clinical depression starts at puberty, if not earlier, and accelerates through the teenage years, peaking around age 19, when it becomes full blown. It is at this time that bipolar disorder and other personality disorders emerge. The ability to think, focus and cope is lost, often resulting in substance abuse as a means of self medication.

What was previously known as melancholia and is now known as clinical depression, major depression, or simply depression and commonly referred to as major depressive disorder by many health care professionals, has a long history, with similar conditions being described at least as far back as classical times.

In Ancient Greece, disease was thought due to an imbalance in the four basic bodily fluids, or humors. Personality types were similarly thought to be determined by the dominant humor in a particular person. Derived from the Ancient Greek melas, "black", and kohl, "bile", melancholia was described as a distinct disease with particular mental and physical symptoms by Hippocrates in his Aphorisms, where he characterized all "fears and despondencies, if they last a long time" as being symptomatic of the ailment.

Aretaeus of Cappadocia later noted that were "dull or stern; dejected or unreasonably torpid, without any manifest cause". The humoral theory fell out of favor but was revived in Rome by Galen. Melancholia was a far broader concept than today's depression; prominence was given to a clustering of the symptoms of sadness, dejection, and despondency, and often fear, anger, delusions and obsessions were included.

Influenced by Greek and Roman texts, physicians in the Persian and then the Muslim world developed ideas about melancholia during the Islamic Golden Age. Ishaq ibn Imran (d. 908) combined the concepts of melancholia and phrenitis. The 11th century Persian physician Avicenna described melancholia as a depressive type of mood disorder in which the person may become suspicious and develop certain types of phobias.

His work, The Canon of Medicine, became the standard of medical thinking in Europe alongside those of Hippocrates and Galen. Moral and spiritual theories also prevailed, and in the Christian environment of medieval Europe, a malaise called acedia (sloth or absence of caring) was identified, involving low spirits and lethargy typically linked to isolation.

The term depression itself was derived from the Latin verb deprimere, "to press down". From the 14th century, "to depress" meant to subjugate or to bring down in spirits. It was used in 1765 in English author Richard Baker's Chronicle to refer to someone having "a great depression of spirit", and by English author Samuel Johnson in a similar sense in 1753.

The term also came in to use in physiology and economics. An early usage referring to a psychiatric symptom was by French psychiatrist Louis Delasiauve in 1856, and by the 1860s it was appearing in medical dictionaries to refer to a physiological and metaphorical lowering of emotional function. Since Aristotle, melancholia had been associated with men of learning and intellectual brilliance, a hazard of contemplation and creativity. The newer concept abandoned these associations and through the 19th century, became more associated with women.

Although melancholia remained the dominant diagnostic term, depression gained increasing currency in medical treatises and was a synonym by the end of the century; German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin may have been the first to use it as the overarching term, referring to different kinds of melancholia as depressive states.

Sigmund Freud likened the state of melancholia to mourning in his 1917 paper Mourning and Melancholia. He theorized that objective loss, such as the loss of a valued relationship through death or a romantic break-up, results in subjective loss as well; the depressed individual has identified with the object of affection through an unconscious, narcissistic process called the libidinal cathexis of the ego. Such loss results in severe melancholic symptoms more profound than mourning; not only is the outside world viewed negatively but the ego itself is compromised. The patient's decline of self-perception is revealed in his belief of his own blame, inferiority, and unworthiness. He also emphasized early life experiences as a predisposing factor.

Meyer put forward a mixed social and biological framework emphasizing reactions in the context of an individual's life, and argued that the term depression should be used instead of melancholia. The first version of the DSM (DSM-I, 1952) contained depressive reaction and the DSM-II (1968) depressive neurosis, defined as an excessive reaction to internal conflict or an identifiable event, and also included a depressive type of manic-depressive psychosis within Major affective disorders.

In the mid-20th century, researchers theorized that depression was caused by a chemical imbalance in neurotransmitters in the brain, a theory based on observations made in the 1950s of the effects of reserpine and isoniazid in altering monoamine neurotransmitter levels and affecting depressive symptoms.

The term Major depressive disorder was introduced by a group of US clinicians in the mid-1970s as part of proposals for diagnostic criteria based on patterns of symptoms (called the "Research Diagnostic Criteria", building on earlier Feighner Criteria), and was incorporated in to the DSM-III in 1980. To maintain consistency the ICD-10 used the same criteria, with only minor alterations, but using the DSM diagnostic threshold to mark a mild depressive episode, adding higher threshold categories for moderate and severe episodes. The ancient idea of melancholia still survives in the notion of a melancholic subtype.

The new definitions of depression were widely accepted, albeit with some conflicting findings and views. There have been some continued empirically based arguments for a return to the diagnosis of melancholia. There has been some criticism of the expansion of coverage of the diagnosis, related to the development and promotion of antidepressants and the biological model since the late 1950s.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) (also known as recurrent depressive disorder, clinical depression, major depression, unipolar depression, or unipolar disorder) is a mental disorder characterized by an all-encompassing low mood accompanied by low self-esteem, and by loss of interest or pleasure in normally enjoyable activities. This cluster of symptoms (syndrome) was named, described and classified as one of the mood disorders in the 1980 edition of the American Psychiatric Association's diagnostic manual. The term "depression" is ambiguous. It is often used to denote this syndrome but may refer to other mood disorders or to lower mood states lacking clinical significance. Major depressive disorder is a disabling condition that adversely affects a person's family, work or school life, sleeping and eating habits, and general health. In the United States, around 3.4% of people with major depression commit suicide, and up to 60% of people who commit suicide had depression or another mood disorder.

The diagnosis of major depressive disorder is based on the patient's self-reported experiences, behavior reported by relatives or friends, and a mental status examination. There is no laboratory test for major depression, although physicians generally request tests for physical conditions that may cause similar symptoms. The most common time of onset is between the ages of 20 and 30 years, with a later peak between 30 and 40 years.

Typically, patients are treated with antidepressant medication and, in many cases, also receive psychotherapy or counseling, although the effectiveness of medication for mild or moderate cases is questionable. Hospitalization may be necessary in cases with associated self-neglect or a significant risk of harm to self or others. A minority are treated with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). The course of the disorder varies widely, from one episode lasting weeks to a lifelong disorder with recurrent major depressive episodes. Depressed individuals have shorter life expectancies than those without depression, in part because of greater susceptibility to medical illnesses and suicide. It is unclear whether or not medications affect the risk of suicide. Current and former patients may be stigmatized.

The understanding of the nature and causes of depression has evolved over the centuries, though this understanding is incomplete and has left many aspects of depression as the subject of discussion and research. Proposed causes include psychological, psycho-social, hereditary, evolutionary and biological factors. Certain types of long-term drug use can both cause and worsen depressive symptoms. Psychological treatments are based on theories of personality, interpersonal communication, and learning. Most biological theories focus on the monoamine chemicals serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine, which are naturally present in the brain and assist communication between nerve cells.

What is depression? PhysOrg - March 11, 2013

Many people know what it's like to feel sad or down from time to time. We can experience negative emotions due to many things - a bad day at work, a relationship break-up, a sad film, or just getting out of bed on the "wrong side". Sometimes we even say that we're feeling a bit "depressed". But what does that mean, and how can we tell when it's more than just a feeling? Depression is more than the experience of sadness or stress. A depressive episode is defined as a period of two weeks or longer where the individual experiences persistent feelings of sadness or loss of pleasure, coupled with a range of other physical and psychological symptoms including fatigue, changes in sleep or appetite, feelings of guilt or worthlessness, difficulty concentrating or thoughts of death. To be diagnosed with major depressive disorder, individuals must experience at least one depressive episode that disrupts their work, social or home life.

Major depression significantly affects a person's family and personal relationships, work or school life, sleeping and eating habits, and general health. Its impact on functioning and well-being has been compared to that of chronic medical conditions such as diabetes.

A person having a major depressive episode usually exhibits a very low mood, which pervades all aspects of life, and an inability to experience pleasure in activities that were formerly enjoyed. Depressed people may be preoccupied with, or ruminate over, thoughts and feelings of worthlessness, inappropriate guilt or regret, helplessness, hopelessness, and self-hatred.

In severe cases, depressed people may have symptoms of psychosis. These symptoms include delusions or, less commonly, hallucinations, usually unpleasant. Other symptoms of depression include poor concentration and memory (especially in those with melancholic or psychotic features), withdrawal from social situations and activities, reduced sex drive, and thoughts of death or suicide. Insomnia is common among the depressed. In the typical pattern, a person wakes very early and cannot get back to sleep. Insomnia affects at least 80% of depressed people. Hypersomnia, or oversleeping, can also happen. Some antidepressants may also cause insomnia due to their stimulating effect.

A depressed person may report multiple physical symptoms such as fatigue, headaches, or digestive problems; physical complaints are the most common presenting problem in developing countries, according to the World Health Organization's criteria for depression. Appetite often decreases, with resulting weight loss, although increased appetite and weight gain occasionally occur.

Family and friends may notice that the person's behavior is either agitated or lethargic. Older depressed people may have cognitive symptoms of recent onset, such as forgetfulness, and a more noticeable slowing of movements. Depression often coexists with physical disorders common among the elderly, such as stroke, other cardiovascular diseases, Parkinson's disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Depressed children may often display an irritable mood rather than a depressed mood, and show varying symptoms depending on age and situation. Most lose interest in school and show a decline in academic performance. They may be described as clingy, demanding, dependent, or insecure. Diagnosis may be delayed or missed when symptoms are interpreted as normal moodiness. Depression may also coexist with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), complicating the diagnosis and treatment of both.

Major depression frequently co-occurs with other psychiatric problems. The 1990-92 National Comorbidity Survey (US) reports that 51% of those with major depression also suffer from lifetime anxiety. Anxiety symptoms can have a major impact on the course of a depressive illness, with delayed recovery, increased risk of relapse, greater disability and increased suicide attempts. American neuroendocrinologist Robert Sapolsky similarly argues that the relationship between stress, anxiety, and depression could be measured and demonstrated biologically. There are increased rates of alcohol and drug abuse and particularly dependence, and around a third of individuals diagnosed with ADHD develop comorbid depression. Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression often co-occur.

Depression and pain often co-occur. This conforms with Seligman's theory of learned helplessness. One or more pain symptoms is present in 65% of depressed patients, and anywhere from five to 85% of patients with pain will be suffering from depression, depending on the setting; there is a lower prevalence in general practice, and higher in specialty clinics. The diagnosis of depression is often delayed or missed, and the outcome worsens. The outcome can also obviously worsen if the depression is noticed but completely misunderstood

Depression is also associated with a 1.5- to 2-fold increased risk of cardiovascular disease, independent of other known risk factors, and is itself linked directly or indirectly to risk factors such as smoking and obesity. People with major depression are less likely to follow medical recommendations for treating cardiovascular disorders, which further increases their risk. In addition, cardiologists may not recognize underlying depression that complicates a cardiovascular problem under their care.

The biopsychosocial model proposes that biological, psychological, and social factors all play a role in causing depression. The diathesis-stress model specifies that depression results when a preexisting vulnerability, or diathesis, is activated by stressful life events. The preexisting vulnerability can be either genetic, implying an interaction between nature and nurture, or schematic, resulting from views of the world learned in childhood.

These interactive models have gained empirical support. For example, researchers in New Zealand took a prospective approach to studying depression, by documenting over time how depression emerged among an initially normal cohort of people. The researchers concluded that variation among the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene affects the chances that people who have dealt with very stressful life events will go on to experience depression. To be specific, depression may follow such events, but seems more likely to appear in people with one or two short alleles of the 5-HTT gene.

In addition, a Swedish study estimated the heritability of depression the degree to which individual differences in occurrence are associated with genetic differences to be around 40% for women and 30% for men, and evolutionary psychologists have proposed that the genetic basis for depression lies deep in the history of naturally selected adaptations. A substance-induced mood disorder resembling major depression has been causally linked to long-term drug use or drug abuse, or to withdrawal from certain sedative and hypnotic drugs.

MRI scans of patients with depression have revealed a number of differences in brain structure compared to those who are not depressed. Recent meta-analyses of neuroimaging studies in major depression, reported that compared to controls, depressed patients had increased volume of the lateral ventricles and adrenal gland and smaller volumes of the basal ganglia, thalamus, hippocampus, and frontal lobe (including the orbitofrontal cortex and gyrus rectus). Hyperintensities have been associated with patients with a late age of onset, and have led to the development of the theory of vascular depression.

There may be a link between depression and neurogenesis of the hippocampus, a center for both mood and memory. Loss of hippocampal neurons is found in some depressed individuals and correlates with impaired memory and dysthymic mood. Drugs may increase serotonin levels in the brain, stimulating neurogenesis and thus increasing the total mass of the hippocampus. This increase may help to restore mood and memory.

Similar relationships have been observed between depression and an area of the anterior cingulate cortex implicated in the modulation of emotional behavior. One of the neurotrophins responsible for neurogenesis is brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). The level of BDNF in the blood plasma of depressed subjects is drastically reduced (more than threefold) as compared to the norm. Antidepressant treatment increases the blood level of BDNF. Although decreased plasma BDNF levels have been found in many other disorders, there is some evidence that BDNF is involved in the cause of depression and the mechanism of action of antidepressants.

There is some evidence that major depression may be caused in part by an overactive hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) that results in an effect similar to the neuro-endocrine response to stress. Investigations reveal increased levels of the hormone cortisol and enlarged pituitary and adrenal glands, suggesting disturbances of the endocrine system may play a role in some psychiatric disorders, including major depression. Oversecretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone from the hypothalamus is thought to drive this, and is implicated in the cognitive and arousal symptoms.

The hormone estrogen has been implicated in depressive disorders due to the increase in risk of depressive episodes after puberty, the antenatal period, and reduced rates after menopause. On the converse, the premenstrual and postpartum periods of low estrogen levels are also associated with increased risk. Sudden withdrawal of, fluctuations in or periods of sustained low levels of estrogen have been linked to significant mood lowering. Clinical recovery from depression postpartum, perimenopause, and postmenopause was shown to be effective after levels of estrogen were stabilized or restored.

Other research has explored potential roles of molecules necessary for overall cellular functioning: cytokines. The symptoms of major depressive disorder are nearly identical to those of sickness behavior, the response of the body when the immune system is fighting an infection. This raises the possibility that depression can result from a maladaptive manifestation of sickness behavior as a result of abnormalities in circulating cytokines.

Some relationships have been reported between specific subtypes of depression and climatic conditions. Thus, the incidence of psychotic depression has been found to increase when the barometric pressure is low, while the incidence of melancholic depression has been found to increase when the temperature and/or sunlight are low.

Various aspects of personality and its development appear to be integral to the occurrence and persistence of depression, with negative emotionality as a common precursor. Although depressive episodes are strongly correlated with adverse events, a person's characteristic style of coping may be correlated with his or her resilience. In addition, low self-esteem and self-defeating or distorted thinking are related to depression. Depression is less likely to occur, as well as quicker to remit, among those who are religious. It is not always clear which factors are causes and which are effects of depression; however, depressed persons who are able to reflect upon and challenge their thinking patterns often show improved mood and self-esteem.

American psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck, following on from the earlier work of George Kelly and Albert Ellis, developed what is now known as a cognitive model of depression in the early 1960s. He proposed that three concepts underlie depression: a triad of negative thoughts composed of cognitive errors about oneself, one's world, and one's future; recurrent patterns of depressive thinking, or schemas; and distorted information processing. From these principles, he developed the structured technique of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). According to American psychologist Martin Seligman, depression in humans is similar to learned helplessness in laboratory animals, who remain in unpleasant situations when they are able to escape, but do not because they initially learned they had no control.

Attachment theory, which was developed by English psychiatrist John Bowlby in the 1960s, predicts a relationship between depressive disorder in adulthood and the quality of the earlier bond between the infant and the adult caregiver. In particular, it is thought that "the experiences of early loss, separation and rejection by the parent or caregiver (conveying the message that the child is unlovable) may all lead to insecure internal working models ... Internal cognitive representations of the self as unlovable and of attachment figures as unloving or untrustworthy would be consistent with parts of Beck's cognitive triad". While a wide variety of studies has upheld the basic tenets of attachment theory, research has been inconclusive as to whether self-reported early attachment and later depression are demonstrably related.

Depressed individuals often blame themselves for negative events, and, as shown in a 1993 study of hospitalized adolescents with self-reported depression, those who blame themselves for negative occurrences may not take credit for positive outcomes. This tendency is characteristic of a depressive attributional, or pessimistic explanatory style. According to Albert Bandura, a Canadian social psychologist associated with social cognitive theory, depressed individuals have negative beliefs about themselves, based on experiences of failure, observing the failure of social models, a lack of social persuasion that they can succeed, and their own somatic and emotional states including tension and stress. These influences may result in a negative self-concept and a lack of self-efficacy; that is, they do not believe they can influence events or achieve personal goals.

An examination of depression in women indicates that vulnerability factors such as early maternal loss, lack of a confiding relationship, responsibility for the care of several young children at home, and unemployment can interact with life stressors to increase the risk of depression. For older adults, the factors are often health problems, changes in relationships with a spouse or adult children due to the transition to a care-giving or care-needing role, the death of a significant other, or a change in the availability or quality of social relationships with older friends because of their own health-related life changes.

The understanding of depression has also received contributions from the psychoanalytic and humanistic branches of psychology. From the classical psychoanalytic perspective of Austrian psychiatrist Sigmund Freud, depression, or melancholia, may be related to interpersonal loss and early life experiences. Existential therapists have connected depression to the lack of both meaning in the present and a vision of the future. The founder of humanistic psychology, American psychologist Abraham Maslow, suggested that depression could arise when people are unable to attain their needs or to self-actualize (to realize their full potential).

Poverty and social isolation are associated with increased risk of mental health problems in general. Child abuse (physical, emotional, sexual, or neglect) is also associated with increased risk of developing depressive disorders later in life. Such a link has good face validity given that it is during the years of development that a child is learning how to become a social being.

Abuse of the child by the caregiver is bound to distort the developing personality and create a much greater risk for depression and many other debilitating mental and emotional states. Disturbances in family functioning, such as parental (particularly maternal) depression, severe marital conflict or divorce, death of a parent, or other disturbances in parenting are additional risk factors.

In adulthood, stressful life events are strongly associated with the onset of major depressive episodes. In this context, life events connected to social rejection appear to be particularly related to depression.Evidence that a first episode of depression is more likely to be immediately preceded by stressful life events than are recurrent ones is consistent with the hypothesis that people may become increasingly sensitized to life stress over successive recurrences of depression.

The relationship between stressful life events and social support has been a matter of some debate; the lack of social support may increase the likelihood that life stress will lead to depression, or the absence of social support may constitute a form of strain that leads to depression directly. There is evidence that neighborhood social disorder, for example, due to crime or illicit drugs, is a risk factor, and that a high neighborhood socioeconomic status, with better amenities, is a protective factor. Adverse conditions at work, particularly demanding jobs with little scope for decision-making, are associated with depression, although diversity and confounding factors make it difficult to confirm that the relationship is causal.

To confer major depressive disorder as the most likely diagnosis, other potential diagnoses must be considered, including dysthymia, adjustment disorder with depressed mood or bipolar disorder. Dysthymia is a chronic, milder mood disturbance in which a person reports a low mood almost daily over a span of at least two years. The symptoms are not as severe as those for major depression, although people with dysthymia are vulnerable to secondary episodes of major depression (sometimes referred to as double depression).

Adjustment disorder with depressed mood is a mood disturbance appearing as a psychological response to an identifiable event or stressor, in which the resulting emotional or behavioral symptoms are significant but do not meet the criteria for a major depressive episode.

Bipolar disorder, also known as manic-depressive disorder, is a condition in which depressive phases alternate with periods of mania or hypomania. Although depression is currently categorized as a separate disorder, there is ongoing debate because individuals diagnosed with major depression often experience some hypomanic symptoms, indicating a mood disorder continuum.

Other disorders need to be ruled out before diagnosing major depressive disorder. They include depressions due to physical illness, medications, and substance abuse. Depression due to physical illness is diagnosed as a mood disorder due to a general medical condition. This condition is determined based on history, laboratory findings, or physical examination. When the depression is caused by a substance abused including a drug of abuse, a medication, or exposure to a toxin, it is then diagnosed as a substance-induced mood disorder. In such cases, a substance is judged to be etiologically related to the mood disturbance.

Schizoaffective disorder is different from major depressive disorder with psychotic features because in the schizoaffective disorder at least two weeks of delusions or hallucinations must occur in the absence of prominent mood symptoms.

Depressive symptoms may be identified during schizophrenia, delusional disorder, and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, and in such cases those symptoms are considered associated features of these disorders, therefore, a separate diagnosis is not deemed necessary unless the depressive symptoms meet full criteria for a major depressive episode. In that case, a diagnosis of depressive disorder not otherwise specified may be made as well as a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Some cognitive symptoms of dementia such as disorientation, apathy, difficulty concentrating and memory loss may get confused with a major depressive episode in major depressive disorder. They are especially difficult to determine in elderly patients. In such cases, the premorbid state of the patient may be helpful to differentiate both disorders. In the case of dementia, there tends to be a premorbid history of declining cognitive function. In the case of a major depressive disorder patients tend to exhibit a relatively normal premorbid state and abrupt cognitive decline associated with the depression. Read more ...

Brain Cells Behind Depression Identified for the First Time SciTech Daily - September 22, 2025

Research on rare post-mortem brain tissue shows changes in gene activity, offering new insight into the biological basis of depression

FDA approves Johnson & Johnson’s nasal spray for depression as stand-alone treatment CNBC - January 23, 2025

The spray, called Spravato, is now the first-ever stand-alone therapy for treatment-resistant depression, which is when trying at least two standard treatments does little to nothing to improve depression symptoms in a patient. Spravato is on its way to becoming a blockbuster product, with the drug bringing in $780 million in sales during the first nine months of 2024 as doctors grow more comfortable using it.

Breakthrough Global Research Finds 293 New Genetic Links to Depression Science Alert - January 17, 2025

Genes play a role in our likelihood of developing depression, and one of the most extensive studies of its kind has now been able to link 293 previously unknown genetic variations to the devastating condition.

There's a Curious Link Between Depression And Body Temperature, Study Finds - Data from 20,880 individuals collected over seven months, confirm that those with depression tend to have higher body temperatures Science Alert - November 3, 2024

There's a Curious Link Between Depression And Body Temperature, Large Study Finds - Those with depression tend to have higher body temperatures Science Alert - February 7, 2024

If something as simple as keeping cool could help tackle the symptoms of depression, then that has the potential to help millions of people around the world.

Despite its popularity among horror-movie mad scientists, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is actually a legitimate treatment for certain mental health disorders, and is effective for up to 80 percent of depressed patients who receive it. IFL Science - January 16, 2024

The technique has been associated with a 'slowing' of brain activity that can last for days to weeks following treatment.

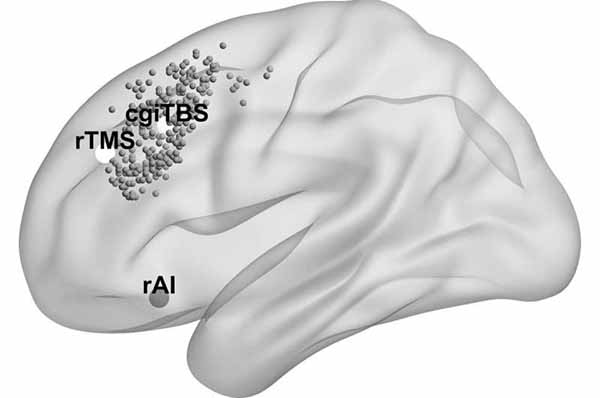

A major clinical trial has shown that by using MRI and tracking to guide the delivery of magnetic stimulation to the brains of people with severe depression, patients will see their symptoms ease for at least six months, which could vastly improve their quality of life. Medical Express - January 16, 2024

Scientists have identified a new subtype of depression that could affect as many as a quarter of all patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) Science Alert - June 27, 2023

The new subtype is unique from other proposed subtypes because it is marked by cognitive deficits in attention, memory, and self-control. These symptoms are often not alleviated by antidepressants that target serotonin, such as Lexapro (escitalopram) or Zoloft (sertraline).

An analysis of published studies suggests that humor therapy may temporarily lessen symptoms of depression and anxiety Medical Express - June 27, 2023

An analysis of published studies suggests that humor therapy may lessen symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Treatment For Depression Changes The Very Structure of The Brain, Scientists Find Science Alert - October 18, 2022

The COVID pandemic triggered an unprecedented rise in deaths around the world, leading to falls in life expectancy. In research last year, we found that 2020 saw significant life expectancy losses, including more than two years in the US and one year in England and Wales.

Individuals who attempt suicide carry an increased genetic liability for depression, regardless of their psychiatric disorder they are affected by Medical Express - June 5, 2019

Suicide is a worldwide public health problem with more than 800,000 deaths due to suicide each year. Suicide and suicide attempts have an emotional toll on families and friends of those who died, as well as on attempt survivors.

There May Be a Link Between Depression and Stroke Live Science - March 6, 2019

Feeling depressed may increase the risk of stroke, at least among older adults, a new study suggests. The study involved about 1,100 people living in New York City; the participants had an average age of 70 and had never had a stroke. At the start of the study, participants filled out a survey designed to measure symptoms of depression, such as feeling sad or feeling like everything is an effort. Based on the survey, the people were given a depression score ranging from 0 to 60, with scores over 16 considered "elevated."

Supplements Don't Prevent Depression, Study Finds Live Science - March 5, 2019

Preventing depression isn't as simple as taking a dietary supplement every day, a new study suggests. The study found that people who took a multivitamin every day for a year were just as likely to develop depression as those who took a placebo. The study was spurred by earlier research suggesting that certain diets and low levels of certain nutrients are linked with a higher risk of depression.

Study firms up diet and depression link Medical Express - October 10, 2018

Does fast food contribute to depression? Can a healthy diet combat mental illness? In an unusual experiment, James Cook University researchers in Australia have found that among Torres Strait Islander people the amount of fish and processed food eaten is related to depression.

National trial: EEG brain tests help patients overcome depression Medical Express - May 16, 2018

Imagine millions of depressed Americans getting their brain activity measured and undergoing blood tests to determine which antidepressant would work best. Imagine some of them receiving "brain training" or magnetic stimulation to make their brains more amenable to those treatments. When the results from these tests are combined, we hope to have up to 80 percent accuracy in predicting whether common antidepressants will work for a patient.

Forty-four genomic variants linked to major depression Science Daily - April 26, 2018

A new meta-analysis of more than 135,000 people with major depression and more than 344,000 controls has identified 44 genomic variants, or loci, that have a statistically significant association with depression.

Why Are So Many People So Unhappy? Live Science - January 25, 2018

The problem is that much of what determines happiness is outside of our control. Some of us are genetically predisposed to see the world through rose-colored glasses, while others have a generally negative outlook. Bad things happen, to us and in the world. People can be unkind, and jobs can be tedious.

Game your brain to treat depression, studies suggest Medical Express - January 4, 2017

Researchers have found promising results for treating depression with a video game interface that targets underlying cognitive issues associated with depression rather than just managing the symptoms. We found that moderately depressed people do better with apps like this because they address or treat correlates of depression.

Scientists find new path in brain to ease depression Medical Express - October 5, 2017

Northwestern Medicine scientists have discovered a new pathway in the brain that can be manipulated to alleviate depression. The pathway offers a promising new target for developing a drug that could be effective in individuals for whom other antidepressants have failed. New antidepressant options are important because a significant number of patients don't adequately improve with currently available antidepressant drugs. The lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder is between 10 to 20 percent of the population.

Faulty gene linked to depression and cardiovascular disease Medical Express - September 13, 2017

Stylistic diagram shows a gene in relation to the double helix structure of DNA and to a chromosome (right). The chromosome is X-shaped because it is dividing. Introns are regions often found in eukaryote genes that are removed in the splicing process (after the DNA is transcribed into RNA): Only the exons encode the protein. The diagram labels a region of only 55 or so bases as a gene. In reality, most genes are hundreds of times longer.