April 13, 2000 - FOX News

And now French and Egyptian archaeologists, armed with a fiber-optic endoscope like those doctors use to peer inside the human body, have discovered two previously unknown chambers and a tunnel that stretches nearly 40 meters (131 feet) into the heart of the enigmatic pyramid.

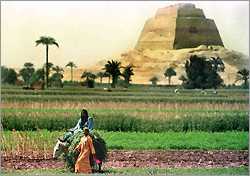

The structure began as a step pyramid, with stair-step sides like a giant wedding cake, in the style of the famous "first pyramid" built at Saqqara for Pharaoh Djoser. Then the steps were expanded by adding another layer. Finally, its steps were encased in a smooth shell to create one of the first true pyramids. Ninety kilometers (56 miles) south of Cairo, it rose nearly 100 meters (330 feet). It likely was unstable from the beginning and seems never to have been used as a tomb.

A tunnel shaft leads from the outside of the mostly collapsed pyramid to the burial chamber deep inside. But, Gaballah Ali Gaballah told the Eighth International Congress of Egyptologists in Cairo Thursday (March 30), two recesses near the bottom of the shaft have confused archaeologists. Gaballah is head of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities.

Each recess is about 1.7 meters (5.7 feet) high and 2.1 meters (6.9 feet) across. An unreinforced span of that size should be too great to support the enormous weight of the stone blocks above it. But the Franco-Egyptian team thinks it has solved the mystery.

The Pyramid of Meidum, nearly 328 feet high, was built in three stages.

Examining the masonry along the top of the shaft revealed what looked like a carefully concealed window. In May 1998, the researchers slipped an endoscope — a device like a long, flexible telescope about the diameter of a human finger — through a joint between building blocks. What they saw through the scope was another tunnel directly above the first. And this one had a "corbelled" roof — a top built of overlapping blocks that rise progressively to a point. Such a roof would distribute the overlying weight and relieve pressure on the open corridor below it. The new shaft does not open on the outside of the pyramid, but it does head down toward the two troublesome recesses.

Last year, the team used the endoscope to explore beyond the end of the tunnel and above the recesses. What they found were two identical corbelled chambers, one above each recess and the same width. This rather clever, weight-distributing construction likely explains how the flat-roofed recesses were made possible.

Gaballah notes that the exact purpose of the complex recesses, chambers, and twin shafts is not clear: "The work is still in progress and we don't know what to expect."

In addition to Gaballah, the team included Mustafa El-Zeiri of Egypt and Gilles Dormion and Jean-Yves Verd'hurt of France.

February 17, 2000 - AP

Sinking water levels have revealed a granite sarcophagus of the ancient Egyptian god Osiris in a 30-metre (98 feet) deep tomb at the Giza pyramids, Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass said.

Osiris was one of the most important gods of ancient Egypt who according to mythology was murdered by his wicked brother Seth. He was buried by Isis, his sister-wife, and brought back to life as judge of the dead and ruler of the underworld.

Hawass said the sarcophagus, which he dated to 500 BC in the New Kingdom, was surrounded by the remains of four pillars built in the shape of a hieroglyphic 'Bir' or 'House of Osiris'.

The excavation unearthed 3,000-year-old bones and pottery found in the underground water, he said.

After dirt and most of the remaining water were cleared from the shaft, located between the Sphinx and the Pyramid of Chefren (Khafre), archaeologists found three underground levels, with the submerged Osiris sarcophagus at the lowest.

February 2, 2000 - Discovering Archaeology

Five rabbits received a pharaoh's honor when they were mummified with the pomp and splendor of Egyptian royalty during an experimental mummification project at the American University in Cairo.

Salima Ikram, assistant professor of Egyptology at AUC and author of the book Equipping the Dead for Eternity, sought answers to questions such as: How were mummies made? How were the materials processed and used? What logistical problems were involved?

During the project, which was done as both research for the Animal Mummy Project in the Cairo Museum that Ikram co-directs, and also as part of her class on "Death in Ancient Egypt," the group experimented with different procedures, since not just one method was used in ancient Egypt. Evisceration (in which the entrails are removed through an incision) and turpentine enemas (which allowed the insides to be flushed out) were the most common. "The method used in antiquity depended on time and finances," says Ikram. The turpentine enema, sometimes made with juniper oil, was a cheaper method than a time-consuming evisceration. The quality of ingredients such as natron or resins, could also hike up costs, as well as the type of bandages and amulets provided.

The spice market where the natron, oils and resins were purchased

The funereal recipes were extracted from varying sources: fifth-century Greek historical accounts from Herodotus; chemical tests; and from a previous successful experiment that Ikram herself performed on food mummies. Insight was also gleaned from previous mummification attempts by American Egyptologist Bob Brier in the 1990s, and the University of Manchester Mummy Project in the 1970s.

The five rabbits -- "available from a local butcher, so we didn't have to kill anything unnecessarily" - were mummified through varying methods, and not all were transformed gracefully into mummies. Two rabbits, which were not eviscerated, exploded. Laughs Ikram, "It was a complete disaster."

The entrails of the remaining three rabbits were removed, including the blood of one animal. The innards were drawn out either through skin incisions, or via turpentine enema. The enema was the second-most successful of the rabbit mummies, and "definitely the most fragrant."

After evisceration, the mummies were plopped in a wooden box of powdered natron (a salt-like mineral, mined in abundance from Egypt's Wadi Natrun) which was left on the roof of AUC's Science Building to desiccate. The drying process is aided by the open wind, and sun, which helps prevent the forming of bacteria.

The rabbit completely immersed in natron

The parched rabbits were then brushed off, and coated with oils and resins to make their bodies more supple before bandaging and to freshen the carcass smell.

"It took us three to four weeks to mummify the animals, but a human is supposed to take 40 days."

The mummification was done with great ceremony. "We even had readings from The Book of the Dead," says Ikram. "Each rabbit was individually wrapped in linen bandages - ears wrapped so they stood up -- with amulets stuffed into the bandages. Some bandages were inscribed with hieroglyphic spells."

The protective spells, listed in The Book of the Dead, contained such well-wishing phrases as "May your head not roll off." Because a dead person was expected to need his body (and amenities like food, furniture, etc.) in the afterlife, great care was taken to make mummies attractive. A mummy losing its head could indeed pose a grave problem, since that person would then remain headless for eternity.

Not only did the mummies enlighten Ikram's class on the correct way to mummify, they also explained some mummification bloopers from antiquity. "For example, reused natron often brings in bits of other mummies, creating a situation in which a duck's feathers sometimes found their way into a rabbit mummy."

The ancient Egyptians mummified more than the human body-- animals were often mummified along with people. The most common type of mummies in ancient Egypt were the votive mummies of cats, ibises, and crocodiles. Food mummies - a piece of mummified meat or poultry thoughtfully placed in a tomb as food for the afterlife - were also common.

The mummies may soon be featured in a display at the American University in Cairo as part of a class on archaeological method and theory, and museology.

January 27, 2000 - Netherlands Organization For Scientific Research

During excavations at Tel Ibrahim Awad in the eastern Nile Delta, Dutch archaeologists discovered a large Middle Kingdom temple. Beneath this building, which dates from around 2000 BC, there were traces of five earlier temples, the earliest dating back to around 3100 BC. This is at least as old as the oldest temple previously discovered, namely at Hierakonpolis. Heavy-duty groundwater pumps had to be brought in to make it possible to reach the earliest remains. Financial support for the excavations was provided by the NWO¼s Council for the Humanities.

The ground plan of the earliest of these temples is unlike anything previously discovered in Egypt, and no other sites are known where a similar series of temples was built one on top of the other and which date back so far. The archaeologists do not yet know which gods were worshipped in the temples. In the third-earliest, they discovered about a thousand "disposable ritual objects", including statuettes of baboons and pottery. According to the laws of the ancient Egyptians, objects which had been used in religious worship must not be profaned and they therefore had to be preserved within the walls of the temple. The objects are currently being studied to see what they can tell us about temple rituals at this early date. No inscriptions were found to provide any clues.

Alongside the temple, a burial ground was discovered containing 50 small-scale tombs from various periods. Excavation of a large First Dynasty tomb (about 3000 BC) uncovered rich finds of pottery and of stone and bronze vessels.

The archaeologists are collaborating under the auspices of the Netherlands Foundation for Archaeological Research in Egypt, linked to Amsterdam University (UvA). They chose the area to be excavated ten years ago on the basis of the remains of walls and fragments of pottery visible on the surface. Increasing population pressure in the Nile Delta is making archaeological investigations more difficult. Only five percent of Egypt is habitable, so that archaeological research has to compete with land cultivation, infrastructure and urban expansion.

August 23, 1999 - AP

A luxurious house under excavation in an ancient Egyptian town belonged to its mayor and is the first such house ever found, said an archaeologist in Pennsylvania.

"It's comparable in scale to a pharaoh's palace of the period," said Josef Wegner, an assistant curator of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. "We know about mayors from ancient Egyptian texts, but never before has the home of a mayor been positively identified."

"We only have a few places where we can learn about daily life in (ancient) Egypt," said William S. Arnett, a professor of ancient history at West Virginia University and author of a book about the origin of hieroglyphics. "It could open up new vistas for us in terms of daily life and public administration."

Wegner said he and other researchers identified the building as the mayor's house this summer in the ancient town called Enduring-are-the-Places-of-Khakaure-maa-kheru-in-Abydos, which dates from the Middle Kingdom from 2000 B.C. to 1700 B.C. The structure, discovered in 1994, dates back 3,700 years.

Researchers in 1997 found thousands of seal impressions, similar to those made with sealing wax, made by ancient Egyptians using clay. The seal impressions gave the names of four mayors, and other seals now illegible may have borne the names of two more mayors, Wegner said.

The town, like many in ancient Egypt, was set up to take care of a pharaoh's mortuary temple, in this case that of King Senwosret III, also known as Sesostris III, who ruled from 1878 B.C. to 1841 B.C. The idea was to create a place that would last forever, dedicated to worship of the dead king. It lasted about 200 years, Wegner said.

"Sesostris III was one of the greatest warrior kings of ancient Egypt, probably one of the greatest warrior kings of antiquity," Arnett said. "His administration was at a peak of prosperity."

For that reason, it's not surprising that the mayor of a town set up to take care of his mortuary temple would have such an elaborate home, he said.

Wegner said the house, about half of which has been excavated, is well-preserved for such an old building. In addition to the many seals that indicate heavy written correspondence, fragments of toys and games also were found in the house.

Wegner said the house was built of brick, plastered throughout, and had a broad front hall with 14 columns running the entire width of the building. Fragments of statuettes, cosmetic coal pots, jewelry and mirrors with ebony and ivory handles show that the mayor had an affluent lifestyle, Wegner said.

The back part of the house was a massive granary, capable of storing great quantities of rations, in which wheat has been identified, Wegner said. The granary was not merely a food storehouse but likely also the town's treasury, he said.

"Grain was essentially the money of ancient Egypt," Wegner said.

Wegner said the clay seals revealed that the first mayor was a man named Nakht. Arnett said Nakht was already known to be a prominent figure in that period of Egyptian history.

Mayors were responsible for serving as the high priest of the nearby temples, administering the major economic activities of the town and serving as a judge to settle disputes, Wegner said. Temples owned endowments of land and mines, so people were employed to work in those commercial ventures to keep money coming in.

Alexandria, Egypt, July 24, 1999 - Reuters -

For more than a thousand years the ancient heart of Alexandria lay buried.

Since tidal waves and earthquakes sent its famed lighthouse and library to the bottom of the Mediterranean, the city of antiquity, lived chiefly in the imagination.

The $190 million library, a tilted white cylinder near the seafront, is due to open next year with a capacity of eight million books. So far it has acquired just 400,000 volumes, 100,000 less than its ancient inspiration.

In the past decade, archaeologists have been excavating on land and exploring underwater to uncover tantalising traces of the city where Cleopatra is said to have gained an audience with Julius Caesar by rolling herself in a carpet in 47 BC.

"You have to imagine that ancient Alexandria is both underwater and above water," said Gaballah Ali Gaballah, head of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. "There are difficulties because modern Alexandria is built over (the old city)."

Archaeologists lament the way they are often forced to race against the timetable of modern developers to rescue parts of Alexandria's long-neglected heritage.

Alexandria, founded by Alexander the Great in 323 BC and then ruled by his general Ptolemy, fell to the Romans in 31 BC.

For the next 300 years Alexandria was relegated to the status of a Roman imperial province, gradually losing touch with the civilisation of its Greek past when scientists of the calibre of Euclid and Eratosthenes studied and taught there.

Grain replaced science as Alexandria's most prized export and successive sackings ruined its beauty.

Arab influence spread after Moslem general Amr Ibn el Asse invaded Egypt in AD 641. The once-bustling port fell into decline after its capture by the Ottomans in 1516, but regained commercial importance when Mohamed Ali encouraged Italian, Armenian, Jewish and French traders in the 19th century.

Napoleon sacked it in 1801, the British navy bombarded it ferociously in 1882 and former Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser extinguished its cosmopolitan flame when he seized the property of foreigners in the 1956 Suez crisis, prompting an exodus.

By this time, Alexandria's past glories had almost vanished, evoked only by a Roman theatre hidden behind a cinema, Pompey's Pillar near the railway station and the Greco-Roman museum.

The tomb of Alexander, who never saw his town complete, is said to lie below the sprawling modern city of three million.

Greek tombs at Kom el Shufaga were discovered in 1900 when a donkey stumbled into them and Polish archaeologists excavated the Roman theatre, found in 1959 under a Moslem cemetery at Kom el Dik. A vast Greek necropolis with more than 240 tomb cavities was discovered in 1996 at Gabbari, just west of the ancient harbour, during work on the foundations of a new road bridge.

Empereur said robbers had stolen all the jewellery from Gabbari tombs, but excavations had yielded vases, oil lamps and incense altars, indicating the funerary customs of the time.

On land, remains of the ancient Greek city are buried far below the surface. Marine archaeologists are focusing new attention on what lies on the largely unexplored seabed.

In 1994 Empereur's divers located what he says are remains of the lighthouse that was one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Destroyed by earthquakes in the 14th century, a Moslem fort was built on its foundations.

In 1996, his team winched from the sea a colossal ancient Egyptian male statue of a Ptolemy represented as a Pharoah, thought to have stood as a companion to that of Isis.

Colin Clement, spokesman for the Centre d'Etudes Alexandrines, said divers had located more than 2,110 architectural blocks and 25 sphinxes by mid-1997, using Global Positioning System (GPS) devices to map them precisely.

Goddio's team has mapped an area about one square km (0.4 square miles) using GPS to fix within 30 cm (one foot) the position of more than 1,000 artefacts and features including sphinxes, columns, and blocks inscribed with hieroglyphs.

June 14, 1999

One of ancient Egypt's most famous artworks has yielded unexpected new evidence of grisly mutilation wrought on defeated enemies. Castration as well as decapitation were employed to ensure that the dead could never be reborn in the next world.

The Palette of Narmer, the principal object surviving from this first Pharaoh's reign some 5,000 years ago, was found in 1898 and has since then graced the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. It is a sheet of slate some 2ft high, with a central depression for the grinding of kohl, a black pigment used as eye makeup in pharaonic times; similar, smaller and more functional palettes are known from many sites, but Narmer's ceremonial piece is highly decorated with scenes of conquest.

The better known front shows Narmer grasping the hair of a defeated enemy, thought to represent his unification of Upper and Lower Egypt into the single kingdom that survived for three millennia, until Roman times. The back shows him in triumphal procession, preceded by standard-bearers.

The headless bodies of ten anonymous enemies lie in front of the procession, their heads placed between their feet and their arms bound.

Vivian Davies of the British Museum says: "The heads, although minuscule in scale, are carefully carved with beards, eyes and eyebrows. All save one are crowned with a curious and much-discussed sausage-shaped object."

When Narmer's Palette was first discovered, at Hierakonpolis on the Nile in Upper Egypt, its discoverer, J.E. Quibell, identified the object as a two-horned cap, while the great Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie suggested the skin and horns of a bull.

Close inspection of the palette shows, however, that either oversight or Victorian prudery made Quibell omit a vital detail from the drawing that most scholars have used for the past century. The head lacking the "sausage-shaped object" lies between the feet of the one figure shown with genitals: "his head, alone, lacks the enigmatic object because the 'object' is still in its original place, protruding from between his legs," Mr. Davies and Dr Friedman point out in Nekhen News.

"Clearly present and visible on good photographs, the object in question is the man's penis. The object on each head is surely nothing other than their otherwise missing member. Severance of the heads and members of the enemy signifies not only their utter humiliation, but also their total extinction in this world and the next."

"The message is clear: Narmer, the King, is the undeniable victor. They can never be reborn. Eternal death, unremembered, is the fate of those who defy him."

Although dismemberment was often used as a symbol of conquest later in Egyptian art, the early date and boldness of Narmer's imagery are striking.

AP - May 21, 1999 - Cairo

A 4,500-year-old road built by the ancient Egyptians has joined the Eiffel Tower and the Statue of Liberty on a list of historic landmarks of engineering.

The road - which runs for more than three miles in Fayoum province, 50 miles southwest of Cairo - is "the oldest surviving paved road in the world," said Jane Howell, press officer of the American Society for Civil Engineers, in Washington on Thursday.

Paved with huge slabs of limestone and sandstone, the road was originally seven miles long and linked quarries to a lake, now called Lake Qarun. Animal-drawn carts transported the quarry stones, some the size of refrigerators, to a quay where they were loaded onto boats, said Mustafa Suleiman, the head of the Egyptian Society for Civil Engineers.

The president of the American Society for Civil Engineers, Daniel S. Turner, dedicated the road on May 15 as a "Civil Engineering Historic Landmark." The society's bronze plaque says construction began in 2575 B.C. and continued with upgrading for 441 years.

The society, based in Reston, Va., conducted three years of research on the road before its engineering historians approved the classification. The society has similarly honored the Eiffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty and the Panama Canal for their contribution to the human race. But, curiously, the society does not consider the pyramids outside Cairo to be landmarks. "We do not live in pyramids. (The road) is more related to our life today than a pyramid," Howell said.

Discovery Online - April 2, 1999

The fabulous treasure of Tutankhamen could help to shed new light on the ancient Egyptian civilization 77 years after the boy pharaoh's tomb was uncovered in the Valley of the Kings at Luxor.

Italian researchers discovered that the scarab at the center of King Tut's pectoral, or necklace, found by Howard Carter in chest n. 267, is not "greenish-yellow chalcedony," as Carter had said, but Libyan desert silica glass, a natural glass that exists only in the remote Great Sand Sea of Egypt -- the Western Desert.

"This is one of Earth's most remote and inhospitable regions," says Giancarlo Negro, the explorer who made the discovery together with geologist Vincenzo De Michele.

Tut's scarab shows that some communication existed between the Western Desert and the Nile Valley during the pharaoh's short reign. It is known that between 2735 and 2195 B.C., Egyptians exploited gold and emerald mines in the mountains of the Eastern Desert, between the Nile and the Red Sea.

But nobody would have imagined that desert silica glass would lie among the pharaoh's gems: In order to set it at the center of the pectoral, the ancient Egyptians would have had to trek across 500 desert miles, half of them without any oasis.

The true nature of the scarab material was revealed by measuring its index of refraction, which was then compared with other pieces of silica glass. The study will be published in the May issue of the journal Sahara.

"Its origin is probably celestial, caused by the impact on the sand of a chondritic meteorite or comet," says De Michele. "The glass is scattered over a 15-mile diameter area, but unfortunately, no crater has been found yet."

James R. Underwood Jr., professor emeritus of geology at Kansas State University, says there might not be a crater. "It could have been produced by a low-altitude explosion of an asteroid or comet. The searing heat from the explosion may have melted surficial material that then cooled quickly to form the glass," he explains.

The elaborate motif of the pectoral, symbolizing the voyage of the sun and moon through the sky, adds a new mystery -- did the ancient Egyptians guess the celestial origins of the desert glass?

By Bassem Mroue - AP - Cairo, Egypt --March 3, 1999

A top Egyptian archaeologist crawled through dusty passageways Wednesday, and during a two-hour search broadcast live to an American audience found a mummy believed to be up to 4,200 years old.

Fox TV broadcast the look into unexplored rooms of two tombs and a small pyramid of Queen Khamerernebty II on the Giza Plateau, site of the Sphinx and the great pyramids on the outskirts of Cairo.

Although the mummy found may be older than the famed 3,300-year-old King Tut discovery in 1922, Giza Plateau's chief archaeologist noted after the broadcast that "it is a regular mummy" - lacking any sort of royal stature.

The remains likely were of the high priest Kai, who performed rituals inside the temples and taught the king's children, Zahi Hawass said.

Hawass had hoped to find the remains of Queen Khamerernebty II, whose pyramid is near the Sphinx. But when he ventured 60 feet down through a narrow passageway, crawling and ducking all the way, he found an incomplete burial chamber. Inside, there was a skeleton he believed could have been a grave robber.

"No pyramid is similar to this at all," he told The Associated Press after the broadcast. "The entrance and the chambers were unfinished and the queen was never buried here. She is buried somewhere else in a tomb and therefore, this pyramid was never used."

Still, Hawass and officials for the American network behind "Opening the Lost Tombs: Live From Egypt," which took place Tuesday evening in the United States - early Wednesday in Cairo - were excited about their project.

"I think it is very good for television to do something different and make archaeology more fun and cool," Fox executive producer Peter Isacksen said.

Paintings on the walls inside the temple of Kai's wife and daughter were the most impressive find, Hawass said. They showed "butchers bringing thighs of cows and it shows people bringing offerings, women standing. ... It's beautiful life scenes."

Hawass said an artist's signature was found in Kai's tomb; in the past, paintings found on the walls have been unsigned. He also discovered a skeleton believed to be that of Kai's wife and another thought to be Kai's daughter.

During the broadcast, Hawass held up several pieces of pottery to the camera, saying they were remnants of jars for drinking beer in the afterlife.

The program cost Fox $3 million, including a contribution to Egypt's antiquities department made in return for government permission for the broadcast, network officials said.