Antioch was an ancient city on the eastern side of the Orontes River. It is near the modern city of Antakya, Turkey. Founded near the end of the 4th century BC by Seleucus I Nicator, one of Alexander the Great's generals, Antioch eventually rivaled Alexandria as the chief city of the Near East and was a cradle of Christianity. It was one of the four cities of the Syrian tetrapolis. Its residents are known as Antiochenes. Once a great metropolis of half a million people, it declined to insignificance during the Middle Ages because of repeated earthquakes, the Crusaders' invasions, and a change in trade routes following the Mongol conquests, which then no longer passed through Antioch from the far east.

Seleucia was the port of Antioch, and capital of Syria in Roman times. The city was founded by Seleucus, hence the name, and lies about 16 miles west of Antioch. There was a strong fortress, and a naval shipyard. Here Seleucus was buried. It was also the commercial port of Antioch. Seleucia retained it's importance in Roman times, becoming the capital of the Roman province of Syria. The city of Antioch became the play-ground of the officials, legates and governors. During the early stages of Christianity, Seleucia had the privilages of a free city, and the remains are numerous. The harbor was enlarged several times under the Romans, especially Diocletian and Constantine. During the Byzantine occupation from 970, followed soon after by the Frankish occupation, Seleucia regained its importance; during the Crusades its port was known by the name of Saint Symeon.

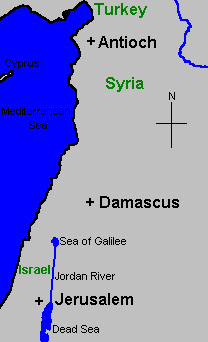

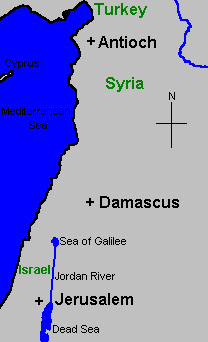

Antioch on the Orontes, also called Syrian Antioch, was situated on the eastern side of the Orontes River, in the far southeastern corner of Asia Minor. Three hundred miles (480 km) north of Jerusalem, the Seleucids urged Jews to move to Antioch, their western capital, and granted them full rights as citizens upon doing so.

In 64 B.C. Pompey made the city capital over the Roman province of Syria. By 165 A.D., it was third largest city of the empire.

Many other cities within the Seleucid empire were also named Antioch, most of them founded by Seleucus I Nicator. It is said of Seleucus I Nicator that "few princes have ever lived with so great a passion for the building of cities. He is reputed to have built in all nine Seleucias, sixteen Antiochs, and six Laodiceas".

Antioch was destined to rival Alexandria in Egypt as the chief city of the nearer East and to be the cradle of gentile Christianity.

The site appears not to have been found wholly uninhabited. A settlement, Meroe, boasting a shrine of Anait, called by the Greeks the "Persian Artemis," had long been located there, and was ultimately included in the eastern suburbs of the new city; and there seems to have been a village on the spur (Mt. Silpius), of which we hear in late authors under the name Io, or Iopolis. This name was always adduced as evidence by Antiochenes (e.g. Libanius) anxious to affiliate themselves to the Attic Ionians--an anxiety which is illustrated by the Athenian types used on the city's coins. At any rate, Io may have been a small early colony of trading Greeks (Javan). John Malalas mentions also a village, Bottia, in the plain by the river.

Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great is said to have camped on the site of Antioch, and dedicated an altar to Zeus Bottiaeus, it lay in the northwest of the future city. This account is found only in the writings of Libanius, a 4th century orator from Antioch, and may be legend intended to enhance Antioch's status. But the story is not unlikely in itself.

After Alexander's death in 323 BC, his generals divided up the territory he had conquered. Seleucus I Nicator won the territory of Syria, and he proceeded to found four "sister cities" in northwestern Syria, one of which was Antioch. Like the other three, Antioch was named by Seleucus for a member of his family. He is reputed to have built sixteen Antiochs.

Seleucus founded Antioch on a site chosen through ritual means. An eagle, the bird of Zeus, had been given a piece of sacrificial meat and the city was founded on the site to which the eagle carried the offering. He did this in the twelfth year of his reign. Antioch soon rose above Seleucia Pieria to become the Syrian capital.

The original city of Seleucus was laid out in imitation of the "gridiron" plan of Alexandria by the architect, Xenarius. Libanius describes the first building and arrangement of this city (i. p. 300. 17). The citadel was on Mt. Silpius and the city lay mainly on the low ground to the north, fringing the river. Two great colonnaded streets intersected in the centre.

Shortly afterwards a second quarter was laid out, probably on the east and by Antiochus I, which, from an expression of Strabo, appears to have been the native, as contrasted with the Greek, town. It was enclosed by a wall of its own. In the Orontes, north of the city, lay a large island, and on this Seleucus II Callinicus began a third walled "city," which was finished by Antiochus III.

A fourth and last quarter was added by Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175-164 BC); and thenceforth Antioch was known as Tetrapolis. From west to east the whole was about 4 miles in diameter and little less from north to south, this area including many large gardens.

Of its population in the Greek and Classical Roman period we know nothing, but it is generally estimated at around 500,000 people living in 15 square kilometers by the 1st century A.D.. In the 4th century A.D. it was about 200,000 according to Chrysostom, who probably did not reckon slaves.

About 4 miles west and beyond the suburb, Heraclea, lay the paradise of Daphne, a park of woods and waters, in the midst of which rose a great temple to the Pythian Apollo, founded by Seleucus I. and enriched with a cult-statue of the god, as Musagetes, by Bryaxis. A companion sanctuary of Hecate was constructed underground by Diocletian. The beauty and the lax morals of Daphne were celebrated all over the western world; and indeed Antioch as a whole shared in both these titles to fame.

Its amenities awoke both the enthusiasm and the scorn of many writers of antiquity.Antioch became the capital and court-city of the western Seleucid empire under Antiochus I, its counterpart in the east being Seleucia on the Tigris; but its paramount importance dates from the battle of Ancyra (240 BC), which shifted the Seleucid centre of gravity from Asia Minor, and led indirectly to the rise of Pergamum.

After that the Seleucids resided at Antioch and treated it as their capital par excellence. We know little of it in the Greek period, apart from Syria, all our information coming from authors of the late Roman time. Among its great Greek buildings we hear only of the theatre, of which substructures still remain on the flank of Silpius, and of the royal palace, probably situated on the island. It enjoyed a great reputation for letters and the arts (Cicero pro Archia, 3); but the only names of distinction in these pursuits during the Seleucid period, that have come down to us, are Apollophanes, the Stoic, and one Phoebus, a writer on dreams.

The mass of the population seems to have been Hellenic, and to have spoken Aramaic. The nicknames which they gave to their later kings were Aramaic; and, except Apollo and Daphne, the great divinities of north Syria seem to have remained essentially native, such as the "Persian Artemis" of Meroe and Atargatis of Hierapolis Bambyce.

The most attractive pleasure resort was the beautiful sacred grove of laurels and cypresses called Daphne, some four or five miles to the west of the city of Antioch. It was renowned for its park-like appearance, for its magnificent temple of Apollo, and for the pompous religious festival held in the month of August. The city was endowed with the right of asylum. From it Antioch was sometimes surnamed Epidaphnes. The population included a great variety of races. There were Macedonians and Greeks, native Syrians and Phoenecians, Jews and Romans, besides a contingent from further Asia; many flocked there because Seleucus had given to all the right of citizenship. Nevertheless, it remained always predominantly a Greek city. The inhabitants did not enjoy a great reputation for learning or virtue; they were excessively devoted to pleasure, and universally known for their witticisms and sarcasm. Not a few of their peculiar traits have reached us through the sermons of St. John Chrysostom, the letters of Libanius, the "Misopogon" of Julian, and other literary sources.

We may infer, from its epithet, "Golden," that the external appearance of Antioch was magnificent; but the city needed constant restoration owing to the seismic disturbances to which the district has always been peculiarly liable. The first great earthquake is said by the native chronicler John Malalas, who tells us most that we know of the city, to have occurred in 148 BC, and to have done immense damage.

The inhabitants were turbulent, fickle and notoriously dissolute. In the many dissensions of the Seleucid house they took violent part, and frequently rose in rebellion, for example against Alexander Balas in 147 BC, and Demetrius II in 129.

The latter, enlisting a body of Jews, punished his capital with fire and sword. In the last struggles of the Seleucid house, Antioch turned definitely against its feeble rulers, invited Tigranes of Armenia to occupy the city in 83, tried to unseat Antiochus XIII in 65, and petitioned Rome against his restoration in the following year.

Its wish prevailed, and it passed with Syria to the Roman Republic in 64 BC, but remained a civitas libera.

Ancient Roman road located in Syria which connected Antioch and Chalcis.

The Romans both felt and expressed boundless contempt for the hybrid Antiochenes; but their emperors favored the city from the first, seeing in it a more suitable capital for the eastern part of the empire than Alexandria could ever be, thanks to the isolated position of Egypt. To a certain extent they tried to make it an eastern Rome. Caesar visited it in 47 BC, and confirmed its freedom. A great temple to Jupiter Capitolinus rose on Silpius, probably at the instance of Octavian, whose cause the city had espoused. A forum of Roman type was laid out. Tiberius built two long colonnades on the south towards Silpius. Agrippa and Tiberius enlarged the theatre, and Trajan finished their work. Antoninus Pius paved the great east to west artery with granite. A circus, other colonnades and great numbers of baths were built, and new aqueducts to supply them bore the names of Caesars, the finest being the work of Hadrian. The Roman client, King Herod, erected a long stoa on the east, and Agrippa encouraged the growth of a new suburb south of this.

The chief events recorded under the empire are the earthquakes that shook Antioch. One, in AD 37, caused the emperor Caligula to send two senators to report on the condition of the city. Another followed in the next reign; and in 115, during Trajan's sojourn in the place with his army of Parthia, the whole site was convulsed, the landscape altered, and the emperor himself forced to take shelter in the circus for several days. He and his successor restored the city; but in 526, after minor shocks, the calamity returned in a terrible form; the octagonal cathedral which had been erected by the emperor Constantius II suffered and thousands of lives were lost, largely those of Christians gathered to a great church assembly. Especially terrific earthquakes on November 29, 528 and October 31, 588 are also recorded.

At Antioch Germanicus died in AD 19, and his body was burnt in the forum. Titus set up the Cherubim, captured from the Jewish temple, over one of the gates. Commodus had Olympic games celebrated at Antioch, and in 266 the town was suddenly raided by the Persians, who slew many in the theatre. In 387 there was a great sedition caused by a new tax levied by order of Theodosius, and the city was punished by the loss of its metropolitan status. Zeno, who renamed it Theopolis, restored many of its public buildings just before the great earthquake of 526, whose destructive work was completed by the Persian Chosroes twelve years later. Justinian I made an effort to revive it, and Procopius describes his repairing of the walls; but its glory was past.

The chief interest of Antioch under the empire lies in its relation to Christianity. Evangelized perhaps by Peter, according to the tradition upon which the Antiochene patriarchate still rests its claim for primacy (cf. Acts xi.), and certainly by Barnabas and Paul, who here preached his first Christian sermon in a synagogue, its converts were the first to be called Christians (Acts 11:26).

They multiplied exceedingly, and by the time of Theodosius were reckoned by Chrysostom at about 100,000 souls. Between 252 and 300 A.D. ten assemblies of the church were held at Antioch and it became the seat of one of the four original patriarchates, along with Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Rome (see Pentarchy). Today Antioch remains the seat of a patriarchate of the Oriental Orthodox churches.

One of the canonical Eastern Orthodox churches is still called the Antiochian Orthodox Church, although it moved its headquarters from Antioch to Damascus, Syria, several centuries ago (see list of Patriarchs of Antioch), and its prime bishop retains the title "Patriarch of Antioch," somewhat analogous to the manner in which several Popes, heads of the Roman Catholic Church remained "Bishop of Rome" even while residing in Avignon, France in the 14th Century of the Common Era.When Julian visited the place in 362 the impudent population railed at him for his favor to Jewish and pagan rites, and to revenge itself for the closing of its great church of Constantine, burned down the temple of Apollo in Daphne.

The emperor's rough and severe habits and his rigid administration prompted Antiochene lampoons, to which he replied in the curious satiric apologia, still extant, which he called Misopogon. His successor, Valens, who endowed Antioch with a new forum having a statue of Valentinian on a central column, reopened the great church, which stood till the sack of Chosroes in 538.

Antioch gave its name to a certain school of Christian thought, distinguished by literal interpretation of the Scriptures and insistence on the human limitations of Jesus. Diodorus of Tarsus and Theodore of Mopsuestia were the leaders of this school. The principal local saint was Simeon Stylites, who performed his penance on a hill some 40 miles east. His body was brought to the city and buried in a building erected under the emperor Leo.

�In 638, during the reign of Heraclius, Antioch passed into Saracen hands and decayed apace for more than 300 years; but in 969 it was recovered for the Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus II Phocas by Michael Burza and Peter the Eunuch. In 1084 the Seljuk Turks captured it but held it only fourteen years, yielding place to the Crusaders, who besieged it for nine months during the First Crusade, enduring frightful sufferings. Being at last betrayed, it was given to Bohemund, prince of Tarentum, and it remained the capital of the Latin Principality of Antioch for nearly two centuries. It fell at last to the Egyptian Mamluk Sultan Baibars, in 1268, after a great destruction and slaughter. Together with the fact that large ships could no longer enter the Orontes because too much sand had accumulated in the river bed over the centuries, that meant it was never to become a major city again, with much of its former role falling to the port city of Alexandretta (Iskenderun).

Few traces of the once great Roman city are visible today aside from the massive fortification walls that snake up the mountains to the east of the modern city, several aqueducts, and the Church of St Peter (St Peter's Cave Church, Cave-Church of St. Peter), said to be a meeting place of an Early Christian community. The majority of the Roman city lies buried beneath deep sediments from the Orontes River, or has been obscured by recent construction.

Between 1932 and 1939, archaeological excavations of Antioch were undertaken under the direction of the "Committee for the Excavation of Antioch and Its Vicinity," which was made up of representatives from the Louvre Museum, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Worcester Art Museum, Princeton University, and later (1936) also the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University and its affiliate Dumbarton Oaks.

The excavation team failed to find the major buildings they hoped to unearth, including Constantine's Great Octagonal Church or the imperial palace. However, a great accomplishment of the expedition was the discovery of high-quality Roman mosaics from villas and baths in Antioch, Daphne and Seleucia. One mosaic includes a border that depicts a walk from Antioch to Daphne, showing many ancient buildings along the way. The mosaics are now displayed in the Hatay Archaeology Museum in Antakya and in the museums of the sponsoring institutions.

A statue in the Vatican and a number of figurines and statuettes perpetuate the type of its great patron goddess and civic symbol, the Tyche (Fortune) of Antioch - a majestic seated figure, crowned with the ramparts of Antioch's walls and holding wheat stalks in her right hand, with the river Orontes as a youth swimming under her feet. According to William Robertson Smith the Tyche of Antioch was originally a young virgin sacrificed at the time of the founding of the city to ensure its continued prosperity and good fortune.

The northern edge of Antakya has been growing rapidly over recent years, and this construction has begun to expose large portions of the ancient city, which are frequently bulldozed and rarely protected by the local museum.

Today the modern city Antakya sits atop much of ancient Antioch and very little remains of the ancient city. Princeton University and the Sorbonne excavated from 1932 to 1939. Finds include city walls, a hippodrome, portions of a Roman aqueduct, masonry works for flood control, and foundations of what may have been Diocletian's Palace. Very little remains of ancient Antioch. This sarcophagus found in the area reminds of the "bulls and garlands" brought to Paul in Lystra (Acts 14:13).

�Little remains now of the ancient city, except colossal ruins of aqueducts and part of the Roman walls, which are used as quarries for modern Antakya; but no scientific examination of the site has been made. A statue in the Vatican and a silver statuette in the British Museum perpetuate the type of its great effigy of the civic Fortune of Antioch--a majestic seated figure, with Orontes as a youth issuing from under her feet.

The environs west and southwest of Aleppo in northern Syria are home to the "Dead Cities" - abandoned ruins of some 700 Byzantine towns, villages and monastic settlements. These ruins are among the greatest treasuries of Byzantine architecture to be found anywhere in the ancient world. Antioch