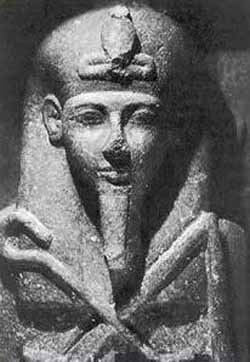

Top of Siptah's Sarcophagus

Top of Siptah's Sarcophagus

Akhenre Setepenre Siptah or Merneptah Siptah was the penultimate ruler of the 19th Dynasty. His father's identity is currently unknown. Both Seti II and Amenmesse have been suggested. He was not the crown prince, but succeeded to the throne as a child after the death of Seti II. His accession date occurred on II Peret day 2 around the month of December.

Historically, it was believed that Queen Tiaa, a wife of Seti II, was the mother of Siptah. This view persisted until it was eventually realized that a relief in the Louvre Museum (E 26901) "pairs Siptah's name together with the name of his mother" a certain Sutailja or Shoteraja.

Sutailja was a Canaanite rather than a native Egyptian name which means that she was almost certainly a king's concubine from Canaan. However, Dodson/Hilton assert that this is not correct and that the lady was, instead, the mother of Ramesses-Siptah and a wife of Ramesses II.

The identity of his father is currently unknown; some Egyptologists speculate it may have been Amenmesse rather than Seti II since both Siptah and Amenmesse spent their youth in Chemmisand both are specifically excluded from Ramesses III's Medinet Habu procession of statues of ancestral kings unlike Merneptah or Seti II. This suggests that Amenmesse and Siptah were inter-related in such a way that they were "regarded as illegitimate rulers and that therefore they were probably father and son.".

A headless statue of Siptah now in Munich shows him seated on the lap of another Pharaoh, presumably his father. The British Egyptologist Aidan Dodson states

"The only ruler of the period who could have promoted such destruction was Amenmesse, and likewise he was the only king whose offspring would have required such explicit promotion. The demolition of this figure is likely to have closely followed the fall of Bay or the death of Siptah himself, when any shortlived rehabilitation of Amenmesse would have ended.

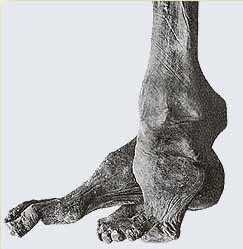

Siptah ruled Egypt for almost 6 years as a young man. His stepmother and Seti II's Chief Queen, Twosret, became the Queen Regent at the Royal Court because of his relative youth. Siptah was only a child of ten or eleven years when he assumed power since a medical examination of his mummy reveals the king to have been a teenager of about 16 years old at death. He was tall at 1.6 metres and had curly reddish brown hair while his left foot was severely deformed presumably from polio.

Siptah's deformed feet

Chancellor Bay publicly boasts that he was instrumental in installing Siptah on the throne in several inscriptions including an Aswan stela set up by Seti, the Viceroy of Kush and at Gebel el-Silsila. Bay, however, later fell out of favour at Court and last appears in public in a dated Year 4 inscription from Siptah's reign. He was executed in the fifth Year of Siptah's reign, on orders of the king himself. News of his execution was passed to the Workmen of Deir el-Medina in Ostraca IFAO 1254. This ostraca was translated and published in 2000 by Pierre Grandet in a French Egyptological journal. Callendar notes that the reason for the king's message to the workmen was to notify them to cease all work on decorating Bay's tomb since Bay had now been deemed a traitor to the state.

Siptah himself died sometime in his 6th regnal Year. After his death, Twosret simply assumed his Regnal Years and ruled Egypt as a Queen for a brief while. Siptah was buried in the Valley of the Kings, in tomb KV47, but his mummy was not found there. In 1898, it was discovered along with 18 others in a mummy cache within the (KV35) tomb of Amenhotep II. An examination of Siptah's mummy reveals that he died around the age of 16 and likely suffered from polio with a severely deformed and crippled left foot. The study of his tomb shows that it was conceived and planned in the same style as those of Twosret and Bay, clearly part of the same architectural design.

KV47 was discovered by Edward Ayrton on December 18th, 1905 while working for Theodore Davis. However, he noted that the debris in the entrance had been partially dug out, creating a passage that subsequently filled back up. In addition, he felt, because of the bad condition of the rock, that the likelihood of finding anything of interest would be slim. Therefore, he only excavated partially down to the antechamber. Later, beginning in 1912, Harry Burton excavated the tomb for Davis, mostly working between the four pillared chamber and up to and including the the burial chamber.

Howard Carter cleared the area around the tomb in 1922, discovering a few objects belonging to this tomb. In the summer of 1994, the local Antiquities Inspectorate cleared what Burton left behind, as well as performing restoration and repair work so that the tomb could be opened for tourists. This work included cleaning and repairing reliefs, filling in gaps with plaster, fixing damaged doorways and the lintels in several chambers, as well as replacing substantially damaged pillars with limestone blocks. They laid down wood floors for walkways, and erected glass panels over painted decorations, and also installed a lighting system.

From these excavations it would appear that Siptah and possibly his mother, Queen Tiaa, a minor wife of Seti II, were both originally buried in the tomb. The evidence suggesting his mother was also buried in this tomb mostly consists of fragmentary calcite canopic equipment, along with a model coffin inscribed with the name of Tiaa and several ostraca found by Carter.

The tomb is found on the north face of a hill that divides the southeast and southwest branches of the central wadi within the Valley of the Kings on the West Bank at Luxor (ancientThebes). It is oriented north-south running fairly straight for a distance of 114.04 meters intothe hill, reaching a depth of about 13.12 meters.

Though the first part of this tomb structure closely follows that of his father, Seti II, the rear sections are somewhat unusual. The initial opening corridor leading into the tomb is in the open air, and consists of a central ramp with two stairways of cut stone blocks imbedded into the bedrock to either side of the ramp. The first true corridor descends, leading to a second level corridor.

Here, we find a pair of beam slots used for lowering the sarcophagus. This corridor gives way to a third corridor that, like the first, descends once more. At the rear of this corridor are a pair of rectangular niches. Afterwards, we find the well room that lacks a shaft, followed by a four pillared chamber The tomb continues through the pillared chamber with a descending passage that leads into the first of two more level corridors before communicating with an antechamber. Normally, we might expect to find a corridor followed by a stairway before the antechamber.

A final wider corridor leads past two abandoned lateral corridors before giving way into the unfinished, transverse burial chamber. Here, a granite sarcophagus is set into an roughly finished rectangular niche in the floor just behind a transverse row of four pillars. The abandoned lateral corridors may have been meant to give into a burial chamber or storage annexes, but this work was stopped after the a corridor broke into the nearby tomb, KV32. The openings were then sealed with limestone slabs.

Due to successive floods, no decorations remain beyond the first four pillared chamber, and little exist beyond the second, level corridor. In addition, this tomb also suffered the fate of KV15, having the cartocuhes of the tomb owner removed, and later re-carved. However, here, we have little idea who originally destroyed the cartouches, or for that matter, who later restored them, though the process probably revolved around the rivalry of Ramesses II's descendants and their quest for the throne after the death of Merenptah.

On the lintel above the doorway to the first true corridor we find the usual scene depicting a scarab and ram headed god flanked by Isis and Nephthys. On the outer thickness and reveals of the door jambs are found the name of the deceased king, along with inscribed prayers to the sun god and Osiris. On the inner thickness of the door jambs is a depiction of the goddess Ma'at, winged and kneeling on baskets supported by the heraldic plants of Upper and Lower Egypt.

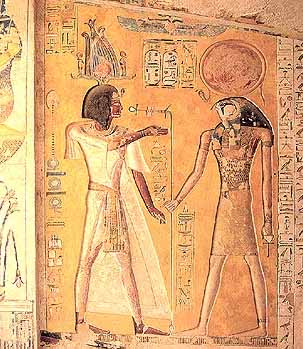

Inside this corridor on the northeast wall is a fairly well preserved depiction of Siptah addressing Re-Horakhty followed by the opening lines of the Litany of Re. Further text and scenes from these passages, including a scene of Anubis before the bier of Osiris, fill the remainder of this wall, the opposite wall, and then flow into the next corridor. On the ceiling of this first corridor we also find representations of a series of flying vultures.

Siptah before Re-Horakhty from the Litany of Re

Within the next (second), level corridor, along with the text from the Litany of Re, are found the 74 forms of Re giving way to two scenes from spell 151 of the Book of the Dead. On the ceiling of this corridor is found the best preserved depiction of Isis and Nephthys as kites to either side of the soul of Re.

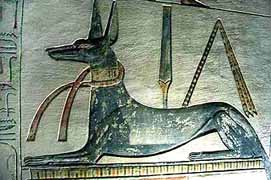

Anubis from the tomb of Siptah

Beyond this, mostly only traces of decorations exist. For example, on the inner thickness of the door jamb into the next descending passage appears the winged figure of Ma'at, but few details are visible. Only fragmentary painted plaster reveal that the forth and fifth hours of the Amduat were once painted upon this corridor's walls.

After the well room on the back wall of the four pillared chamber, we can just barely make out a fragment of plaster that once portrayed the god Osiris in a shrine. This was probably once a double scene of Siptah making offerings to the god of the underworld, as found in other tombs in the Valley. While no other decorations survive in this tomb, there are a few red painted mason's guidelines indicating a doorway that was never cut into the west wall of the pillared chamber. It would have probably led to an annex.

In addition, we may also make out four pairs of vertical red lines that would have marked the location for a second row of pillars within the burial chamber.

Burial Chamber and Sarcophagus

The only material item of funerary equipment found within KV47 was the red granite outer sarcophagus of Siptah. It is shaped like a cartouche, with the image of the king carved into the upper surface of the lid. He is flanked by figures of Isis and Nephthys and surrounded by a crocodile, a snake and a pair of cobras with human heads and arms. The sarcophagus box is decorated with alternating triple khekher-ornaments and recumbent jackals surmounting a register of underworld demons. This was a new composition that subsequently was used by other kings on their sarcophagi through the reign of Ramesses VI. Interestingly, there was no destruction of Siptah's name on his sarcophagus.

Otherwise, only fragmentary funerary equipment was discovered, including a calcite inner mummform sarcophagus decorated with passages from the Book of Gates and the Amduat, along with calcite canopic equipment for Siptah and his mother, calcite shabtis figures for Siiptah, and possibly a sarcophagus for queen Tiaa. All of these calcite fragments are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the New York.

Burton discovered bones within Siptah's sarcophagus, but it is now believed that this was an intrusive burial, probably of the Third Intermediate Period. In fact, Siptah's mummy has been identified as one of those moved to the cache in tomb KV35 belonging to Amenhotep II.