June 29, 2001 - Reuters - Cairo

In a first, a joint team of German and Egyptian archaeologists has unearthed a royal tomb dating back to the 17th Dynasty which likely belonged to a king whose great-grandsons swept out foreign rulers and paved the way for the New Kingdom - Ancient Egypt's "Golden Age". The German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo (DAI), in announcing the find, said they are convinced the 3500-year-old tomb belonged to Nub-Kheper-Ra Intef, a monarch of the late 17th Dynasty. A time of political turmoil and confusion, the 17th Dynasty has failed to provide archaeologists with a royal tomb for study - until now.

The tomb is located across the Nile from modern-day Luxor in the northern portion of the Theban necropolis, at the entrance to the Valley of the Kings. The area, referred to as Dra' Abu el-Naga, has long been felt to be the burial place of kings and private individuals of the 17th and early 18th dynasties. According to archaeologists, the "remnants of the tomb consist of the lower part of a small mud-brick pyramid surrounded by an enclosure wall, also built of mud bricks."

In front of the pyramid lies a burial shaft where the toppled head of a life-size royal sandstone statue of the pharaoh was found. The pyramid-complex and the burial shaft is unequivocally that of Nub-Kheper-Ra Intef, according to Dr Daniel Polz, the lead excavator and deputy director of DAI.

Other discoveries included "a small funerary chapel of a private individual" adjacent to the pyramid, but outside the enclosure wall. The inner walls of the chapel were decorated with depictions of its owner, as well as his name and titles. According to these inscriptions the tomb owner, Teti, was a "treasurer" or "chancellor" of the king. On one of the walls, there remains a large cartouche (the royal name-ring) showing the name of king Nub-Kheper-Ra Intef. The 17th Dynasty at the end of the Second Intermediate Period - the era between the Middle and New Kingdoms - was characterized by the rule of the Hyksos, foreign invaders of an Asiatic origin who ruled in the northern part of Egypt contemporaneously with the kings of the 17th Dynasty in Thebes.

Following numerous military campaigns against them, the Hyksos rulers were eventually expelled from Egypt by Kamose, the last king of the 17th Dynasty and his brother, Ahmose, the first king of the 18th Dynasty which saw a unified Egypt rise to unprecedented wealth and power. It is believed that Nub-Kheper-Ra Intef, one of the immediate predecessors of Kamose and Ahmose, could actually have been their great-grandfather.

German archaeologist Polz and his team were led to the tomb by information obtained from a 3000-year-old papyrus and the works of an American archaeologist who made reference to the tomb, but never found it himself. The papyrus mentioned an attempt by robbers to plunder the royal tomb by digging a tunnel from another tomb belonging to a private individual. The robbers, however, failed to reach the royal tomb. Then in the 19th Century, another group of robbers found the royal tomb, removed the golden casket and sold it without disclosing where they found it - the casket eventually ended up in the British Museum in London. Polz and his team also found what appeared to be evidence of the removal of two obelisks from the tomb of King Nub-Kheper-Ra Intef. The obelisks were reportedly removed from the tomb in 1881 on orders of the then French director of the Council of Antiquities in Cairo, who wanted them transferred to old Cairo Museum. Unfortunately, the boat with the heavy obelisks sank in the Nile, some 10 kilometres from Luxor.

June 2001 - Egypt Revealed

In the middle of the fourth century A.D., a group of hermits, followers of St. Macarius, settled in the Egyptian desert west of the Nile Delta. At Wadi al-Natrun, this colony of anchorites (religious believers who choose to live in isolation) survived the harshness of the desert and the raids of nomads over the centuries and evolved into what was probably one of the first monastic communities of Egypt.

A team from Leiden University in the Netherlands has been excavating this site since 1995, and the results so far are beginning to paint a reliable image of how this evolution from hermits to monastery monks came about.

Initially, the settlement must have had a rather open, informal structure, similar to that of a village. The core of the settlement consisted of a church and a defensive tower. The remains of a church, excavated in 1999, are of a rather late date, probably the early eighth century, although an earlier church might still be found underneath it. Shortly after A.D. 700, the monasteries of Wadi al-Natrun were sacked by Bedouins, and this eighth-century church, apparently one of the first buildings to be reconstructed, is little more than a makeshift structure.

Remnants of a huge building were found immediately south of the church, in the southeast corner of the complex. It must have been a square tower about 16 meters (52 feet) on a side, with walls 2 meters (6.5 feet) thick and a height of as much as 20 meters (65 feet).

Much evidence suggests this tower existed in the fifth century and may date to the fourth century. The fact that blocks from a pharaonic temple were found in the debris of the church suggests that this tower was built to guard a settlement of workers producing salt and natron (sodium carbonate) from nearby lakes. Such a settlement would have included a temple and, if abandoned before the monks arrived, it might have served as a quarry for building materials.

The region was invaded by Bedouins over the following centuries, and the settlements were destroyed or heavily damaged several times. After the sack around 700 and the makeshift rebuilding effort, the monks apparently no longer relied on the crumbling tower for defense. But in the ninth century, the towers outer walls were reinforced and the core of the settlement was surrounded by a defensive wall, giving it the appearance of a real monastery. This new physical structure may have influenced the social structure of the community. Instead of living some distance apart in hermitages sprinkled over a wide area, many monks may have chosen to live within the safety of the enclosure wall. The result would have been a true monastery.

May 31, 2001 - Reuters

Fossilized remains of a gargantuan plant-eating dinosaur, the second most massive animal ever to walk the Earth, have been unearthed in a desert oasis in Egypt at a site that eons ago was a lush coastal paradise, researchers said on Thursday. The discovery of a partial skeleton of Paralititan stromeri was made by 31-year-old University of Pennsylvania doctoral student Joshua Smith, who went on a dinosaur hunt at a remote site that had yielded spectacular finds in the first half of the 20th century in expeditions led by German paleontologist Ernest Stromer von Reichenbach. But the fossils of the four new dinosaurs Stromer uncovered were lost to the world during World War Two when British warplanes bombed the Bayerische Staatssammlung museum during a raid over Munich on April 24, 1944.

Stromer's excavation site remained largely ignored in the decades since then.

Paralititan (pronounced pah-ral-ih-TY-tan and meaning ''tidal giant'') lived 94 million years ago during the middle of the Cretaceous period of the Mesozoic Era. The long-necked, long-tailed quadruped looked much like the familiar Brontosaurus (formal name Apatosaurus) that lived tens of millions of years earlier, except that its back may have been studded with bony body armor as protection from predators.

The finding was published in the journal Science. "We think that a large individual might have massed about 70 tons, 75 tons maybe and it might have approached 100 feet in length. As far as tall, stack four African elephants on top of each other. That's about the height. It would look through a third-story window without much problem.'' The only dinosaur known to be heavier than Paralititan is Argentinosaurus, which looked much like the new dinosaur (both are classified as titanosaurid sauropods) but is estimated to have been about 7 percent more massive. The remains of only one example of these two colossal dinosaurs exist. Smith found the partial skeleton preserved in fine-grained sediments full of plant remains and root casts in the Bahariya Oasis in the Sahara desert some 180 miles southwest of Cairo. He said the evidence suggests that the arid Bahariya site once resembled the tropical mangrove coasts of Florida, a low-energy, shallow water area of tidal flats and tidal channels. He compares it to the Everglades. Based in part on Stromer's earlier finding of three massive carnivorous dinosaurs at the site, Smith said the area must have been teeming with life.

Smith believes the massive herbivore was standing on the edge of a tidal channel in very shallow water when it died. His team also found evidence that the carcass had been scavenged by a flesh-eating dinosaur, including a tooth that may come from Carcharodontosaurus, whose name means ''shark-tooth lizard'' and whose size, 45 feet (13.5 meters) long, was comparable to Tyrannosaurus rex. In addition, the pelvis was ripped apart as if it had been eaten. It's unclear whether Paralititan lost a life-or-death struggle with the predator or became a meal after dying for other reasons, Smith said. ``All we know is that the animal died and somebody came along and munched on it.'' Smith said the skeleton of Paralititan is only 20 to 25 percent complete. Most impressive is a humerus (upper forelimb bone) that measures 6 foot, 7 inches long. The remains also include several vertebrae, ribs and both shoulder blades. The Penn team also found fossils of fish, sharks, turtles, marine reptiles and other dinosaurs.

Dumb luck played a role in the discovery, Smith admits. He and University of Pennsylvania graduate student Matthew Lamanna, who at age 25 is a co-author of the study, dreamed up the idea of finding the sites that had been so productive for Stromer, who worked there extensively starting in 1911. Smith said in 1999 he tagged along on another Penn expedition to Egypt and was given all of two days to search for dinosaurs. Another problem was finding the Stromer's exact site because he did not leave behind any maps or directions. Scientific literature found in Cairo pointed the way, but Smith ended up in the wrong place anyway. But as luck would have it, on Feb. 23, 1999, Smith spotted from the window of his Toyota Land Cruiser three pieces of Paralititan's forelimb.

February 12, 2001 - Cairo - Reuters

A tomb dating back to the reign of New Kingdom Pharaoh Amenhotep IV in the 14th century BC has been discovered in the Giza suburb of Sakkara, an antiquities official said on Sunday. "This is a unique discovery because it is the first time we have uncovered a tomb in Sakkara from the reign of Akhenaton, who had his capital at Akhetaton (now called Tel al-Amarna) in Upper Egypt,'' Adel Hussein, director of Sakkara at the Supreme Antiquities Council, told Reuters. The tomb once occupied by the high priest Meryneith, whose name means "the beloved of Neith (goddess of war and hunting),'' was discovered by a Dutch-Egyptian archaeological mission on January 31 during excavation of New Kingdom tombs at Sakkara.

The excavation work, which is still under way, has so far uncovered two store rooms in the east of the tomb, three small chapels in the west, wall reliefs that include depictions of funeral rituals, five columns with hieroglyphic inscriptions and a burial chamber, Hussein noted.

No mummies have yet been uncovered, but we have come across bones. There is a good chance we will find a mummy once excavation work on the burial chamber is complete. Hussein sees the discovery as an addition to our knowledge of the reign of Amenhotep IV and Sakkara, which was used as a site for pyramids and tombs from the first Pharaonic dynasties. In his quest to unify Egypt in the worship of a single deity, Aton -- a form of the sun-god Ra --, the 18th dynasty ruler Amenhotep IV changed his name to Akhenaton, meaning ``it pleases Aton,'' and built a new capital in Amarna dedicated to Aton and called it ``Akhetaton'' (the Horizon of Aton). Akhenaton, a religious hard-liner who provoked the wrath of the powerful Amun priesthood, among others, for his reforms, is said by some scholars to have been the world's first monotheist. He ruled from 1353-36 BC.

The reconstructed mummy

December 22, 2000 - BBC

The discovery of a false toe attached to the foot of an mummy provides more evidence of the sophistication of ancient Egyptian medicine. The well-crafted wooden toe was discovered by a team investigating remains found in a burial chamber believed to be in the ancient city of Thebes. Pottery fragments found in the chamber dated the find at approximately the 21st or 22nd Egyptian dynasty, or between 1065BC and 740BC.

They found that the woman, aged between 50 and 55 at death had lost the big toe on the right foot - probably by amputation - during life, as soft tissue and skin had regrown over the wound. In addition, a wooden prosthetic toe - perfectly shaped to match the lost toe, even to the point of having a nail - had been created and attached to the foot with textile laces.

The regrowth of tissue, allied with definite scuff marks on the base of the wooden toe, seem to indicate a functional role rather than simply an effort by embalmers to make the body appear complete in readiness for the afterlife. Examination of the rest of the body suggest that this may well be one of the earliest examples of someone suffering diabetic complications. The woman had suffered significant hardening of the arteries, but not just the large arteries, but also the tiny vessels supplying the extremities. Although they cannot prove this, the researchers suggest that the toe may have had to be amputated after the blood supply was cut, and gangrene set in.

November 20, 2000 - Reuters - Abu Sir

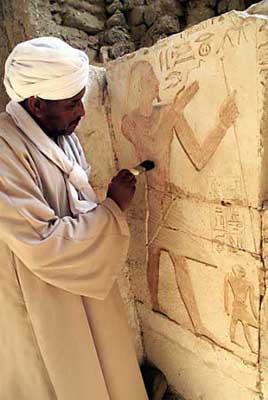

Galal Abdu al Keriti, an Egyptian antiquities worker, dusts off a newly-discovered Pharaonic portrait of Queen Inty near the Giza plateau November 20, 2000. The portrait was among finds, which included an empty sarcophagus, in a 4,000-year-old tomb being excavated by a Czech-Egyptian team of archaeologists. Archaeologists excavating a 4,000-year-old tomb near Cairo found an empty sarcophagus on Monday that they said could yield vital clues about the collapse of the pyramid-building era in ancient Egypt. Zahi Hawass, director of the Giza Plateau, told Reuters that a team of Egyptian and Czech archaeologists discovered the stone coffin in a sixth dynasty tomb at the pyramids of Abu Sir 17 miles southwest of Cairo.

The method was accurate for only a few years

November 15, 2000 - BBC

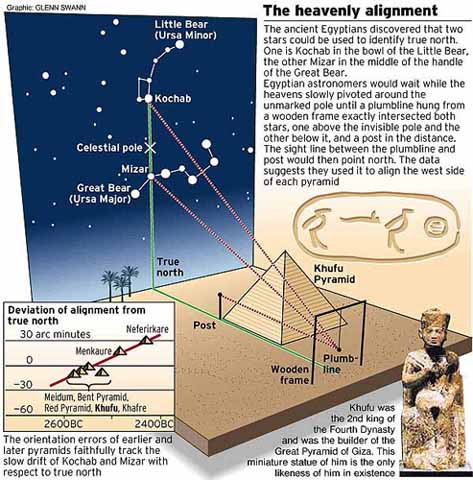

Ancient Egyptian astronomers aligned the pyramids due north by using two stars that circle the celestial polar point.Spence has come up with an ingenious solution to a long-standing mystery. Nearly 4,500 years ago, each star was about 10 degrees from the celestial pole which lay directly between them. When one star was exactly above the other in the sky, astronomers could find a line that pointed due north. But the alignment was only true for a few years around 2,500 BC. Before and after that time, the stars deviated from the north-south line and anyone using the stars to plot a direction would have made errors. And it is these mistakes that a British Egyptologist now believes can be used to estimate very accurately when the pyramids were built. Her theory suggests that the Great Pyramid at Giza was constructed within 10 years of 2,480 BC.

Kate Spence is from the University of Cambridge. She developed her theory while trying to explain the deviations in the alignment of the bases of many pyramids from true north.

She believes the ancients may have used a pair of fairly bright stars, which in 2,467 BC lay precisely along a straight line that included the celestial pole. "We know that the ancient Egyptians were extremely interested in the night sky, particularly the circumpolar stars. These circle around the North Pole, and as you can always see them, the Egyptians always referred to them as 'The Indestructibles'. As a result, they became closely associated with eternity and the king's afterlife. So that after death, the king would hope to join the circumpolar stars - and that's why the pyramids were laid out towards them.

The pyramid builders may have used a pair of stars for alignment

The north-finding stars were Kochab, in the bowl of the Little Dipper (Ursa Minor), and Mizar, in the middle of the handle of The Plough or Big Dipper (Ursa Major).

An Egyptian astronomer would have held up a plumb line and waited for the night sky to slowly pivot around the unmarked pole as the Earth rotated.

When the plumb line exactly intersected both stars, one about 10 degrees above the invisible pole and the other 10 degrees below it, the sight line to the horizon would aim directly north.

However, the Earth's axis is unstable and wobbles like a gyroscope over a period of 26,000 years. Modern astronomers now know that the celestial north pole was exactly aligned between Kochab and Mizar only in the year 2,467 BC.

Either side of this date, the ancient astronomers trying to find true north would lose some accuracy.

Writing in the journal Nature, Kate Spence shows that the orientation errors of earlier and later pyramids faithfully track the slow drift of Kochab and Mizar with respect to true north.

And because the error in the Kochab-Mizar alignment can be readily calculated for any date, the error in each pyramid's orientation corresponds to a period of several years.

Owen Gingerich, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, Massachusetts, said: "Spence has come up with an ingenious solution to a long-standing mystery."

Oct. 23, 2000 - AP

A team of U.S. archaeologists has unearthed the earliest known example of an ancient Egyptian solar barge, team leader said Monday. The barge dates back to the first Pharaonic dynasty around 5,000 years ago, they said. The royal boat was excavated in May and June at the southern Egyptian funerary site of Abydos near the Nile River, said Matthew Adams, the team's associate director. "The substantial size shows that the Egyptians were already masters of boat construction by this early period and the use of imported wood shows that they already had extensive trade contacts," he said.

The U.S. team is certain the boat was built from non-native timber, possibly cedar wood from Lebanon, for one of the pharoahs of the first dynasty (3100 to 2890 BC), making it the oldest solar boat yet unearthed, Adams said. Such boats, buried in pits on land next to royal burial chambers, may have been used for the pharoah's funerary procession while others may have been intended for his use in the afterworld in travels with the sun god. The boat was excavated from one of 14 mud brick boat pits so far discovered at the site in Abydos, 300 miles south of Cairo. It measures 75 feet long, 7 feet wide and 2.5 feet deep, a statement from the Egyptian ministry of culture said.

August 5, 2000 - Discovery

According to an analysis of the clothing found in Tutankhamen's tomb, the ancient pharaoh was pear-shaped and may have suffered from a disease that gave him huge hips. In an eight-year study, Vogelsang-Eastwood, curator at the Ethnological Museum in Leiden, Netherlands, found that the pharaoh, who was only 18 when he died in about 1323 BC, measured 31 inches around the chest, 29 inches around the waist, and 43 inches around the hips, according to the London Times. Vogelsang-Eastwood believes that being pear-shaped may have run in the family, considering the pharaoh's father Akhenaten had a similar figure.

She said, "This is shown on statues and reliefs of Akhenaten. But by the time of Tutankhamen, Egypt had returned to the old religion, and reliefs were idealized - they show him as a golden boy." According to Vogelsang-Eastwood, father and son may have suffered from an inherited disease or one common to the area, although she has no idea as to what it might be. She told the Times, "Not enough medical research has been done in this area. The disease, or whatever he had, certainly affected his weight, putting fatty deposits on his hips." A leading expert on Tutankhamen's wardrobe, Vogelsang-Eastwood began her study in 1992, a time when little research on the textiles had been done since they were found in 1922. She used the hundreds of items found in his tomb, including garments he was buried in and clothing dating from his childhood, to create exact copies of the pharaoh's clothing. Tutankhamen's recreated wardrobe will be featured in an exhibition in Edinburgh early next year.

July 23, 2000 - Discovery

Two mini-replicas of the great pyramids of Giza have been unearthed south of the Sphinx, at the eastern foot of the three great pyramids. Containing the bodies of the workers who built the pyramids and their supervisors, the limestone tombs may throw new light on the knowledge of the funerary traditions in ancient Egypt. Built 4,600 years ago, during the reign of the pharaoh Cheops, the tombs are modeled exactly on the design made to house kings, with false doors and causeways leading to an offering basin.

The upper-level tombs, made in limestone, were reserved for technicians, craftsmen and artisans, while the lower-level tombs, made with "leftovers" from the pyramids construction, housed the bodies of the workmen who positioned the huge stone blocks. Like the great pyramids, the workers tombs bore inscriptions depicting the worker's title - such as "Inspector of Pyramid Building" - curses to ward off sacrilegious visitors, and even frescoes showing builders at work with a customary dress very similar to the galabiyas, the traditional garb peasants still wear today.

The skeletons found in the tombs show that the workforce also received good health care. Twelve skeletons had splints on their hands for injuries probably caused by falling rocks; one had an amputated leg and lived for 14 years after the surgery. Moreover, X-rays on a skull revealed what may be one of the earliest examples of brain surgery. Egyptologists are intrigued. "The imitation of elements of the royal pyramid complex in these private tombs is a process seen also at other periods, by which the fashions and styles of the elite were copied by other levels of society, " said Alan Jeffrey Spencer of the British Museum.

July 16, 2000 - London Times

More than 3,000 years after it was stolen from a tomb in Egypt, scientists believe they have found the body of Ramses I, who is thought to have been the pharaoh at the time of the Exodus recounted in the Old Testament. The mummy was discovered in a private museum at Niagara Falls where it had lain unrecognised for 140 years.

American Egyptologists who bought the remains are awaiting the results of DNA tests. They hope these will back up evidence from the body's provenance and appearance which suggest that it is Ramses. They will compare material taken from the body with DNA samples from Ramses I's son, Sethi I, and his grandson, Ramses II. The Egyptologists at the Michael C Carlos Museum in Atlanta, Georgia, say clues suggest it is the body of a pharaoh even though the 5ft 5in man has lost his original coffins and bandage wrappings. He lies in a cardboard box, head tilted back and arms crossed across his chest. "The arms are crossed in a way which is generally only seen in royal mummies and the incisions made in its side to allow the removal of internal organs also correspond to the techniques used on the pharaohs," said Betsy Teasley Trope, the assistant curator of antiquities. Her museum bought the remains last year from the owner of the Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum.

Museum records show that in 1861 Colonel Sydney Barnett, the son of its founder, bought five mummies from James Douglas, an adventurer who may have bought them during a visit to Thebes in Upper Egypt around 1860. It is believed that one of these bodies came from a cache of royal mummies that was discovered near Thebes and later transferred to Cairo.

June 24, 2000 - AP

Two mini-replicas of the great pyramids of Giza have been unearthed south of the Sphinx, at the eastern foot of the three great pyramids. Containing the bodies of the workers who built the pyramids and their supervisors, the limestone tombs may throw new light on the knowledge of the funerary traditions in ancient Egypt.

"Now we can say that pyramid-shaped tombs were not a privilege reserved to kings and nobility. Ordinary people were also allowed to use the pyramid design to construct their own tombs," said Zahi Hawass, director of the Giza plateau where the pyramids are located, announcing the discovery on Thursday.

Built 4,600 years ago, during the reign of the pharaoh Cheops, the tombs are modeled exactly on the design made to house kings, with false doors and causeways leading to an offering basin. The upper-level tombs, made in limestone, were reserved for technicians, craftsmen and artisans, while the lower-level tombs, made with "leftovers" from the pyramids construction, housed the bodies of the workmen who positioned the huge stone blocks.

Like the great pyramids, the workers tombs bore inscriptions depicting the worker's title - such as "Inspector of Pyramid Building" - curses to ward off sacrilegious visitors, and even frescoes showing builders at work with a customary dress very similar to the galabiyas, the traditional garb peasants still wear today. Hawass said that the skeletons found in the tombs show that the workforce also received good health care. Twelve skeletons had splints on their hands for injuries probably caused by falling rocks; one had an amputated leg and lived for 14 years after the surgery. Moreover, X-rays on a skull revealed what may be one of the earliest examples of brain surgery. The findings dispel once and for all the popular belief that the pyramids were built by whip-driven slaves: "This care would not have been given to slaves," he said.

AP - June 13, 2000

Archaeologists found in late May a hidden chamber containing a statue of what is thought to be Ramses II, ruler of Egypt more than 3,000 years ago. Above, a relief depicting Ramses as a young man. Statues of a pharaoh thought to be Ramses II and an ancient cow goddess, their colors intact, have been discovered in a hidden chamber at a necropolis south of Cairo. The three-foot-high statue of the king and the taller sculpture of Hathor, goddess of love and happiness and guardian of cemeteries, were found in a sealed room beneath the Saqqara funerary chapel of Ramses II's treasurer, Necheruymes, who lived more than 3,200 years ago. Alain Zivie of France's national science research center said he and his team made an opening in a chapel wall that appeared to date back to the later Greco-Roman period, and came face to face May 21 with the two statues.

The pharaoh was wearing a yellow headdress with blue stripes, the traditional royal cobra over his forehead and false beard on his chin. Hathor, who was standing protectively over the king, was depicted with her long horns twisted into the shape of a lyre. Zivie said the discovery was the logical next step of a breakthrough his team made in 1996.

Four years ago, the Egyptologist discovered a series of tombs in a cliff on the edge of the Saqqara necropolis that had housed the remains of New Kingdom pharaonic dignitaries including Maia, the nurse of Tutankhamun. This year, they were exploring a gallery that ran along the edge of the nearby richly colored chapel of Necheruymes, who is believed to have negotiated a peace accord with the Hittites, the other great Middle Eastern empire of Ramses II's day. The French team ran into a wall, which they breached. "The two statues were standing in a room several meters deep which could lead to funerary chambers," Zivie said.

The archeologists are waiting for the next excavation season in the cooler temperatures of October and have in the meantime re-sealed the wall to protect the statues from curious people and the ravages of the climate. Zivie, who has been excavating for 20 years in Saqqara, discovered on the same site in 1987 the vault of pharaoh Akhenaton's prime minister, or vizir, Aper-El, which contained a wealth of funerary treasure.

Reuters - June 7, 2000

Archaeologists aren't exaggerating when they say ancient treasures abound in the sands of Egypt. So many, in fact, that even a pilot from Iowa, out on a desert outing, can make a notable discovery: cave drawings that could date back thousands of years before the birth of Christ. George Cunningham was in the desert 25 miles southeast of Cairo looking for fossilized sea urchins, shells and plants - a favorite hobby - when he spotted "an interesting looking wall" late last month. Cunningham led Egyptian scholars to the site to investigate the find - a sort of cave in a limestone hill.

The cave drawings appear to be from three eras, according to Egyptian experts. The earliest, which could date back to 7000-6500 B.C., are hunting scenes: men and women carrying bows alongside what appear to be dogs or wolves. A later drawing appears to be religious: two gods or goddesses in an arch alongside three shapely women - probably goddesses as well. It could date to the early Pharaonic dynastic period, around 3,000-2500 B.C., the experts say.

From yet another era comes writing that includes hieroglyphic elements, like a primitive version of an eye of Horus. Specialists speculate that it could represent a transition between languages, either before or after hieroglyphics. Archaeologists have found similar drawings in caves in southern Egypt. But, says el-Saghir, this may be the first time such etchings have been found in northern Egypt. If anything, it could help mark the route that Stone Age nomads took from southern Egypt to the Nile Valley to settle in what is now Ma'adi, a posh Cairo suburb, el-Saghir said. Those Bedouin later became the Ma'adi civilization, established around 3200 B.C., about 1,000 years before the Early Dynastic Period.

FOX - April 13, 2000

And now French and Egyptian archaeologists, armed with a fiber-optic endoscope like those doctors use to peer inside the human body, have discovered two previously unknown chambers and a tunnel that stretches nearly 40 meters (131 feet) into the heart of the enigmatic pyramid.

The structure began as a step pyramid, with stair-step sides like a giant wedding cake, in the style of the famous "first pyramid" built at Saqqara for Pharaoh Djoser. Then the steps were expanded by adding another layer. Finally, its steps were encased in a smooth shell to create one of the first true pyramids. Ninety kilometers (56 miles) south of Cairo, it rose nearly 100 meters (330 feet). It likely was unstable from the beginning and seems never to have been used as a tomb.

A tunnel shaft leads from the outside of the mostly collapsed pyramid to the burial chamber deep inside. But, Gaballah Ali Gaballah told the Eighth International Congress of Egyptologists in Cairo Thursday (March 30), two recesses near the bottom of the shaft have confused archaeologists. Gaballah is head of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities. Each recess is about 1.7 meters (5.7 feet) high and 2.1 meters (6.9 feet) across. An unreinforced span of that size should be too great to support the enormous weight of the stone blocks above it. But the Franco-Egyptian team thinks it has solved the mystery.

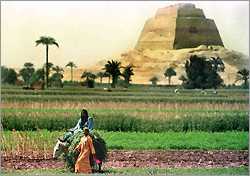

The Pyramid of Meidum, nearly 328 feet high, was built in three stages.

Examining the masonry along the top of the shaft revealed what looked like a carefully concealed window. In May 1998, the researchers slipped an endoscope — a device like a long, flexible telescope about the diameter of a human finger — through a joint between building blocks. What they saw through the scope was another tunnel directly above the first. And this one had a "corbelled" roof — a top built of overlapping blocks that rise progressively to a point. Such a roof would distribute the overlying weight and relieve pressure on the open corridor below it. The new shaft does not open on the outside of the pyramid, but it does head down toward the two troublesome recesses.

Last year, the team used the endoscope to explore beyond the end of the tunnel and above the recesses. What they found were two identical corbelled chambers, one above each recess and the same width. This rather clever, weight-distributing construction likely explains how the flat-roofed recesses were made possible. Gaballah notes that the exact purpose of the complex recesses, chambers, and twin shafts is not clear: "The work is still in progress and we don't know what to expect." In addition to Gaballah, the team included Mustafa El-Zeiri of Egypt and Gilles Dormion and Jean-Yves Verd'hurt of France.

AP - February 17, 2000

Sinking water levels have revealed a granite sarcophagus of the ancient Egyptian god Osiris in a 30-metre (98 feet) deep tomb at the Giza pyramids, Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass said. Osiris was one of the most important gods of ancient Egypt who according to mythology was murdered by his wicked brother Seth. He was buried by Isis, his sister-wife, and brought back to life as judge of the dead and ruler of the underworld.

Hawass said the sarcophagus, which he dated to 500 BC in the New Kingdom, was surrounded by the remains of four pillars built in the shape of a hieroglyphic 'Bir' or 'House of Osiris'. The excavation unearthed 3,000-year-old bones and pottery found in the underground water, he said. After dirt and most of the remaining water were cleared from the shaft, located between the Sphinx and the Pyramid of Chefren (Khafre), archaeologists found three underground levels, with the submerged Osiris sarcophagus at the lowest.

February 2, 2000 - Discovering Archaeology

Five rabbits received a pharaoh's honor when they were mummified with the pomp and splendor of Egyptian royalty during an experimental mummification project at the American University in Cairo. Salima Ikram, assistant professor of Egyptology at AUC and author of the book Equipping the Dead for Eternity, sought answers to questions such as: How were mummies made? How were the materials processed and used? What logistical problems were involved?

During the project, which was done as both research for the Animal Mummy Project in the Cairo Museum that Ikram co-directs, and also as part of her class on "Death in Ancient Egypt," the group experimented with different procedures, since not just one method was used in ancient Egypt. Evisceration (in which the entrails are removed through an incision) and turpentine enemas (which allowed the insides to be flushed out) were the most common. "The method used in antiquity depended on time and finances," says Ikram. The turpentine enema, sometimes made with juniper oil, was a cheaper method than a time-consuming evisceration. The quality of ingredients such as natron or resins, could also hike up costs, as well as the type of bandages and amulets provided.

The spice market where the natron, oils and resins were purchased

The funereal recipes were extracted from varying sources: fifth-century Greek historical accounts from Herodotus; chemical tests; and from a previous successful experiment that Ikram herself performed on food mummies. Insight was also gleaned from previous mummification attempts by American Egyptologist Bob Brier in the 1990s, and the University of Manchester Mummy Project in the 1970s.

The five rabbits -- "available from a local butcher, so we didn't have to kill anything unnecessarily" - were mummified through varying methods, and not all were transformed gracefully into mummies. Two rabbits, which were not eviscerated, exploded. Laughs Ikram, "It was a complete disaster."

The entrails of the remaining three rabbits were removed, including the blood of one animal. The innards were drawn out either through skin incisions, or via turpentine enema. The enema was the second-most successful of the rabbit mummies, and "definitely the most fragrant."

After evisceration, the mummies were plopped in a wooden box of powdered natron (a salt-like mineral, mined in abundance from Egypt's Wadi Natrun) which was left on the roof of AUC's Science Building to desiccate. The drying process is aided by the open wind, and sun, which helps prevent the forming of bacteria.

The rabbit completely immersed in natron

The parched rabbits were then brushed off, and coated with oils and resins to make their bodies more supple before bandaging and to freshen the carcass smell. "It took us three to four weeks to mummify the animals, but a human is supposed to take 40 days."

The mummification was done with great ceremony. "We even had readings from The Book of the Dead," says Ikram. "Each rabbit was individually wrapped in linen bandages - ears wrapped so they stood up -- with amulets stuffed into the bandages. Some bandages were inscribed with hieroglyphic spells."

The protective spells, listed in The Book of the Dead, contained such well-wishing phrases as "May your head not roll off." Because a dead person was expected to need his body (and amenities like food, furniture, etc.) in the afterlife, great care was taken to make mummies attractive. A mummy losing its head could indeed pose a grave problem, since that person would then remain headless for eternity.

Not only did the mummies enlighten Ikram's class on the correct way to mummify, they also explained some mummification bloopers from antiquity. "For example, reused natron often brings in bits of other mummies, creating a situation in which a duck's feathers sometimes found their way into a rabbit mummy."

The ancient Egyptians mummified more than the human body-- animals were often mummified along with people. The most common type of mummies in ancient Egypt were the votive mummies of cats, ibises, and crocodiles. Food mummies - a piece of mummified meat or poultry thoughtfully placed in a tomb as food for the afterlife - were also common. The mummies may soon be featured in a display at the American University in Cairo as part of a class on archaeological method and theory, and museology.

January 27, 2000 - Netherlands Organization For Scientific Research

During excavations at Tel Ibrahim Awad in the eastern Nile Delta, Dutch archaeologists discovered a large Middle Kingdom temple. Beneath this building, which dates from around 2000 BC, there were traces of five earlier temples, the earliest dating back to around 3100 BC. This is at least as old as the oldest temple previously discovered, namely at Hierakonpolis. Heavy-duty groundwater pumps had to be brought in to make it possible to reach the earliest remains. Financial support for the excavations was provided by the NWO's Council for the Humanities.

The ground plan of the earliest of these temples is unlike anything previously discovered in Egypt, and no other sites are known where a similar series of temples was built one on top of the other and which date back so far. The archaeologists do not yet know which gods were worshipped in the temples. In the third-earliest, they discovered about a thousand "disposable ritual objects", including statuettes of baboons and pottery. According to the laws of the ancient Egyptians, objects which had been used in religious worship must not be profaned and they therefore had to be preserved within the walls of the temple. The objects are currently being studied to see what they can tell us about temple rituals at this early date. No inscriptions were found to provide any clues. Alongside the temple, a burial ground was discovered containing 50 small-scale tombs from various periods. Excavation of a large First Dynasty tomb (about 3000 BC) uncovered rich finds of pottery and of stone and bronze vessels.

The archaeologists are collaborating under the auspices of the Netherlands Foundation for Archaeological Research in Egypt, linked to Amsterdam University (UvA). They chose the area to be excavated ten years ago on the basis of the remains of walls and fragments of pottery visible on the surface. Increasing population pressure in the Nile Delta is making archaeological investigations more difficult. Only five percent of Egypt is habitable, so that archaeological research has to compete with land cultivation, infrastructure and urban expansion.

AP - August 23, 1999

A luxurious house under excavation in an ancient Egyptian town belonged to its mayor and is the first such house ever found, said an archaeologist in Pennsylvania. "It's comparable in scale to a pharaoh's palace of the period," said Josef Wegner, an assistant curator of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. "We know about mayors from ancient Egyptian texts, but never before has the home of a mayor been positively identified. Wegner said he and other researchers identified the building as the mayor's house this summer in the ancient town called Enduring-are-the-Places-of-Khakaure-maa-kheru-in-Abydos, which dates from the Middle Kingdom from 2000 B.C. to 1700 B.C. The structure, discovered in 1994, dates back 3,700 years.

Researchers in 1997 found thousands of seal impressions, similar to those made with sealing wax, made by ancient Egyptians using clay. The seal impressions gave the names of four mayors, and other seals now illegible may have borne the names of two more mayors, Wegner said.

The town, like many in ancient Egypt, was set up to take care of a pharaoh's mortuary temple, in this case that of King Senwosret III, also known as Sesostris III, who ruled from 1878 B.C. to 1841 B.C. The idea was to create a place that would last forever, dedicated to worship of the dead king. It lasted about 200 years, Wegner said.

"Sesostris III was one of the greatest warrior kings of ancient Egypt, probably one of the greatest warrior kings of antiquity," Arnett said. "His administration was at a peak of prosperity." For that reason, it's not surprising that the mayor of a town set up to take care of his mortuary temple would have such an elaborate home, he said.

Wegner said the house, about half of which has been excavated, is well-preserved for such an old building. In addition to the many seals that indicate heavy written correspondence, fragments of toys and games also were found in the house. It was built of brick, plastered throughout, and had a broad front hall with 14 columns running the entire width of the building. Fragments of statuettes, cosmetic coal pots, jewelry and mirrors with ebony and ivory handles show that the mayor had an affluent lifestyle, Wegner said. The back of the house was a massive granary, capable of storing great quantities of rations, in which wheat has been identified, Wegner said. The granary was not merely a food storehouse but likely also the town's treasury, he said. "Grain was essentially the money of ancient Egypt," Wegner said. Wegner said the clay seals revealed that the first mayor was a man named Nakht. Arnett said Nakht was already known to be a prominent figure in that period of Egyptian history.

Mayors were responsible for serving as the high priest of the nearby temples, administering the major economic activities of the town and serving as a judge to settle disputes, Wegner said. Temples owned endowments of land and mines, so people were employed to work in those commercial ventures to keep money coming in.

Alexandria, Egypt, July 24, 1999 - Reuters

For more than a thousand years the ancient heart of Alexandria lay buried.

Since tidal waves and earthquakes sent its famed lighthouse and library to the bottom of the Mediterranean, the city of antiquity, lived chiefly in the imagination. The $190 million library, a tilted white cylinder near the seafront, is due to open next year with a capacity of eight million books. So far it has acquired just 400,000 volumes, 100,000 less than its ancient inspiration.

In the past decade, archaeologists have been excavating on land and exploring underwater to uncover tantalising traces of the city where Cleopatra is said to have gained an audience with Julius Caesar by rolling herself in a carpet in 47 BC.

Alexandria, founded by Alexander the Great in 323 BC and then ruled by his general Ptolemy, fell to the Romans in 31 BC. For the next 300 years Alexandria was relegated to the status of a Roman imperial province, gradually losing touch with the civilisation of its Greek past when scientists of the calibre of Euclid and Eratosthenes studied and taught there.

Grain replaced science as Alexandria's most prized export and successive sackings ruined its beauty. Arab influence spread after Moslem general Amr Ibn el Asse invaded Egypt in AD 641. The once-bustling port fell into decline after its capture by the Ottomans in 1516, but regained commercial importance when Mohamed Ali encouraged Italian, Armenian, Jewish and French traders in the 19th century.

Napoleon sacked it in 1801, the British navy bombarded it ferociously in 1882 and former Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser extinguished its cosmopolitan flame when he seized the property of foreigners in the 1956 Suez crisis, prompting an exodus. By this time, Alexandria's past glories had almost vanished, evoked only by a Roman theatre hidden behind a cinema, Pompey's Pillar near the railway station and the Greco-Roman museum. The tomb of Alexander, who never saw his town complete, is said to lie below the sprawling modern city of three million.

Greek tombs at Kom el Shufaga were discovered in 1900 when a donkey stumbled into them and Polish archaeologists excavated the Roman theatre, found in 1959 under a Moslem cemetery at Kom el Dik. A vast Greek necropolis with more than 240 tomb cavities was discovered in 1996 at Gabbari, just west of the ancient harbour, during work on the foundations of a new road bridge. Empereur said robbers had stolen all the jewellery from Gabbari tombs, but excavations had yielded vases, oil lamps and incense altars, indicating the funerary customs of the time.

On land, remains of the ancient Greek city are buried far below the surface. Marine archaeologists are focusing new attention on what lies on the largely unexplored seabed.

In 1994 Empereur's divers located what he says are remains of the lighthouse that was one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Destroyed by earthquakes in the 14th century, a Moslem fort was built on its foundations.

In 1996, his team winched from the sea a colossal ancient Egyptian male statue of a Ptolemy represented as a Pharoah, thought to have stood as a companion to that of Isis.

Colin Clement, spokesman for the Centre d'Etudes Alexandrines, said divers had located more than 2,110 architectural blocks and 25 sphinxes by mid-1997, using Global Positioning System (GPS) devices to map them precisely. Goddio's team has mapped an area about one square km (0.4 square miles) using GPS to fix within 30 cm (one foot) the position of more than 1,000 artefacts and features including sphinxes, columns, and blocks inscribed with hieroglyphs.

June 14, 1999

One of ancient Egypt's most famous artworks has yielded unexpected new evidence of grisly mutilation wrought on defeated enemies. Castration as well as decapitation were employed to ensure that the dead could never be reborn in the next world.

The Palette of Narmer, the principal object surviving from this first Pharaoh's reign some 5,000 years ago, was found in 1898 and has since then graced the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. It is a sheet of slate some 2ft high, with a central depression for the grinding of kohl, a black pigment used as eye makeup in pharaonic times; similar, smaller and more functional palettes are known from many sites, but Narmer's ceremonial piece is highly decorated with scenes of conquest.

The better known front shows Narmer grasping the hair of a defeated enemy, thought to represent his unification of Upper and Lower Egypt into the single kingdom that survived for three millennia, until Roman times. The back shows him in triumphal procession, preceded by standard-bearers.

The headless bodies of ten anonymous enemies lie in front of the procession, their heads placed between their feet and their arms bound.

Vivian Davies of the British Museum says: "The heads, although minuscule in scale, are carefully carved with beards, eyes and eyebrows. All save one are crowned with a curious and much-discussed sausage-shaped object."

When Narmer's Palette was first discovered, at Hierakonpolis on the Nile in Upper Egypt, its discoverer, J.E. Quibell, identified the object as a two-horned cap, while the great Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie suggested the skin and horns of a bull.

Close inspection of the palette shows, however, that either oversight or Victorian prudery made Quibell omit a vital detail from the drawing that most scholars have used for the past century. The head lacking the "sausage-shaped object" lies between the feet of the one figure shown with genitals: "his head, alone, lacks the enigmatic object because the 'object' is still in its original place, protruding from between his legs," Mr. Davies and Dr Friedman point out in Nekhen News.

"Clearly present and visible on good photographs, the object in question is the man's penis. The object on each head is surely nothing other than their otherwise missing member. Severance of the heads and members of the enemy signifies not only their utter humiliation, but also their total extinction in this world and the next. The message is clear: Narmer, the King, is the undeniable victor. They can never be reborn. Eternal death, unremembered, is the fate of those who defy him." Although dismemberment was often used as a symbol of conquest later in Egyptian art, the early date and boldness of Narmer's imagery are striking.

AP - May 21, 1999 - Cairo

A 4,500-year-old road built by the ancient Egyptians has joined the Eiffel Tower and the Statue of Liberty on a list of historic landmarks of engineering.

The road - which runs for more than three miles in Fayoum province, 50 miles southwest of Cairo - is "the oldest surviving paved road in the world," said Jane Howell, press officer of the American Society for Civil Engineers, in Washington on Thursday.

Paved with huge slabs of limestone and sandstone, the road was originally seven miles long and linked quarries to a lake, now called Lake Qarun. Animal-drawn carts transported the quarry stones, some the size of refrigerators, to a quay where they were loaded onto boats, said Mustafa Suleiman, the head of the Egyptian Society for Civil Engineers.

The president of the American Society for Civil Engineers, Daniel S. Turner, dedicated the road on May 15 as a "Civil Engineering Historic Landmark." The society's bronze plaque says construction began in 2575 B.C. and continued with upgrading for 441 years.

The society, based in Reston, Va., conducted three years of research on the road before its engineering historians approved the classification. The society has similarly honored the Eiffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty and the Panama Canal for their contribution to the human race. But, curiously, the society does not consider the pyramids outside Cairo to be landmarks. "We do not live in pyramids. (The road) is more related to our life today than a pyramid," Howell said.

AP - March 3, 1999

A top Egyptian archaeologist crawled through dusty passageways Wednesday, and during a two-hour search broadcast live to an American audience found a mummy believed to be up to 4,200 years old. Fox TV broadcast the look into unexplored rooms of two tombs and a small pyramid of Queen Khamerernebty II on the Giza Plateau, site of the Sphinx and the great pyramids on the outskirts of Cairo. Although the mummy found may be older than the famed 3,300-year-old King Tut discovery in 1922, Giza Plateau's chief archaeologist noted after the broadcast that "it is a regular mummy" - lacking any sort of royal stature. The remains likely were of the high priest Kai, who performed rituals inside the temples and taught the king's children, Zahi Hawass said.

Hawass had hoped to find the remains of Queen Khamerernebty II, whose pyramid is near the Sphinx. But when he ventured 60 feet down through a narrow passageway, crawling and ducking all the way, he found an incomplete burial chamber. Inside, there was a skeleton he believed could have been a grave robber.

Paintings on the walls inside the temple of Kai's wife and daughter were the most impressive find, Hawass said. They showed "butchers bringing thighs of cows and it shows people bringing offerings, women standing. It's beautiful life scenes." Hawass said an artist's signature was found in Kai's tomb; in the past, paintings found on the walls have been unsigned. He also discovered a skeleton believed to be that of Kai's wife and another thought to be Kai's daughter. During the broadcast, Hawass held up several pieces of pottery to the camera, saying they were remnants of jars for drinking beer in the afterlife.